Читать книгу Stepan Bandera: The Life and Afterlife of a Ukrainian Fascist - Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe - Страница 9

The Person

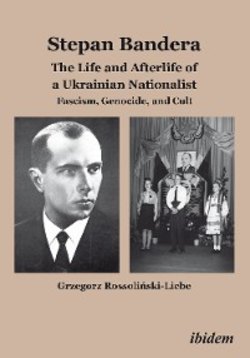

ОглавлениеEven without the cult that arose during his lifetime and flourished after his death, Stepan Bandera was an intriguing person. It was not purely by chance that he became one of the central symbols of Ukrainian nationalism, although the role of chance in history should not be underestimated. With his radical nature, doctrinaire determination, and strong faith in an ultranationalist Ukrainian revolution that was intended to bring about the “rebirth” of the Ukrainian nation, Bandera fulfilled the ideological expectations of his cohorts. By the time he was twenty-six, he was admired not only by other Ukrainian revolutionary ultranationalists but also by some other elements of Ukrainian society living in the Second Polish Republic. The same factors made him the leader (Ukr. Providnyk or Vozhd’), and symbol of the most violent, twentieth century, western Ukrainian political movement: the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (Orhanizatsia Ukraїns’kykh Natsionalistiv, OUN), which in late 1942 and early 1943 formed the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (Ukraїns’ka Povstans’ka Armiia, UPA). Despite, or perhaps because of the fact that Bandera spent a significant part of his life outside Ukraine, in prison or other confinement, he became a legendary personality after whom thousands of his followers, sympathizers and even ordinary western Ukrainians were called Banderites (Ukr. banderivtsi, Pol. banderowcy, Rus. banderovtsi). There are also those who think that his remarkable-sounding name, meaning “banner” in Polish and Spanish, contributed to his becoming the symbol of Ukrainian nationalism.

A biographical investigation of Bandera is challenging. His political myth is embedded in different ideologies, which have distorted the perception of the person. Not without reason do the Bandera biographies that have appeared in Poland, Russia and Ukraine since 1990 differ greatly from one another and inform us very little about the person and related history. Very few of them examine archival documents. Many are couched in various post-Soviet nationalist discourses. Their authors present Bandera as a national hero, sometimes even as a saint, and ignore or deny his radical worldview and his followers’ contribution to ethnic and political violence. Others present Bandera as a biblical kind of evil and deny war crimes committed against Ukrainian civilians by the Poles, Germans, and Soviets. Earlier publications on Bandera written during the Cold War were either embedded in Soviet discourse or, more frequently, in the nationalist discourse of the Ukrainian diaspora.

The investigation of Bandera requires not only a comparison of his biographies and other publications relating to him, but, more important, the examination of numerous archival documents, memoirs written by persons who knew him, and documents and publications written by him personally. The study of these documents reveals how Bandera acted at particular stages of his life, and how he was perceived by his contemporaries. This enables us to understand Bandera’s role in twentieth-century Ukrainian history and helps us look for answers to the most difficult questions related to his biography, such as if and to what extent he was responsible for OUN and UPA atrocities, in which he was personally not involved but which he approved of.