Читать книгу Stepan Bandera: The Life and Afterlife of a Ukrainian Fascist - Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe - Страница 14

Sacralization of Politics

and the Heroization-Demonization Dichotomy

ОглавлениеThe sacralization of politics is a theoretical concept related to the previously discussed notions of cult, myth, charisma, and fascism. Emilio Gentile, one of the leading theorists of this concept, argued that totalitarian movements and regimes have the tendency to sacralize politics and to create political religions. According to Gentile, the “sacralisation of politics takes place when politics is conceived, lived and represented through myths, rituals, and symbols that demand faith in the sacralised secular entity, dedication among the community of believers, enthusiasm for action, and a warlike spirit and sacrifice in order to secure its defense and its triumph.”[64]

When analyzing the radical and revolutionary form of Ukrainian nationalism, which was deeply influenced by religion, it is important to keep in mind that the “sacralization of politics does not necessarily lead to conflict with traditional religions, and neither does it lead to a denial of the existence of any supernatural supreme being.”[65] On the contrary, the relationship between political and traditional religion is very complex. Political religions take over religious elements and “transform them into a system of beliefs, myths and rituals,” in consequence of which, the boundaries between them frequently blur: ordinary individuals are transformed into worshipers, political symbols became sacralized, and national heroes are perceived as secular saints.[66]

Gentile correctly observed that the sacralization of politics in the twentieth century was catalyzed by the First World War, during which several countries used God and religion to legitimize violence. After the war, even movements that had been declared to be atheist or anti-religious used religious symbols to legitimize their ideologies and to attract the masses. The cult of the fallen, heroes and martyrs, the symbolism of death and resurrection, dedication to and exaltation of the nation, and the mystic qualities of blood and sacrifice were very common elements of militarist and totalitarian movements.[67] The sacralization of the state was another significant variety of political religion, which became especially important in the Ukrainian context. When Ukrainians did not succeed in establishing a state, the attempt to do so became, for the Ukrainian revolutionary nationalists, a matter of life and death.[68]

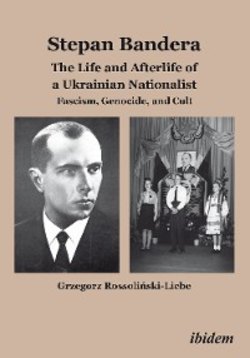

After the Second World War, because of specific political circumstances, elements of the Ukrainian revolutionary nationalists continued to sacralize politics, especially in the diaspora. Both before and after Bandera’s assassination, his cult was composed of various religious elements. After his death, the transformation of Bandera into a martyr was one of them. In order to explore this matter, Gentile’s approach will be combined with Clifford Geertz’s concept of “thick description.” Using descriptive analyses of its rituals and its creation of various hagiographic items, we will try to understand the meaning of the Bandera cult, and the role it has played in the invention of Ukrainian tradition.[69]

Related to the question of sacralization is the heroization-demonization dichotomy. This notion will be explored in this study, but it should not prevent us from uncovering Bandera’s life and the history of his movement. The depiction of individuals as heroes and villains, or friends and enemies, is an intrinsic element of totalitarian ideologies. The main question to be investigated in this context is: Which ideology met what kind of needs, while depicting Bandera as a hero, or as a villain, and what kind of hero or villain did Bandera become?[70]

The investigation of Bandera, the OUN, and Ukrainian nationalism must also relate to the Soviet Union and Soviet ideology. The OUN perceived the Soviet Union as its most important enemy, before—and especially after—Jews and Poles had largely disappeared from Ukraine. Bandera’s ultranationalist revolution after the Second World War was intended to take place in Soviet Ukraine and was directed against Soviet power. What is more, Soviet propaganda created its own Bandera image, which, during the Cold War, affected the perception of Bandera in the Western bloc and, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, in post-Soviet Ukraine. Therefore, the investigation of Soviet questions concerning Bandera and Ukrainian revolutionary nationalism is an important aspect of this study.[71]