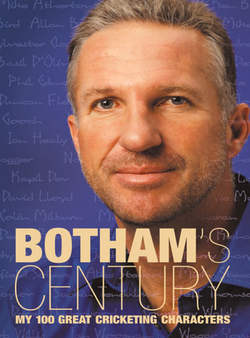

Читать книгу Botham’s Century: My 100 great cricketing characters - Ian Botham, Ian Botham - Страница 10

Ken Barrington

ОглавлениеKenny Barrington and I shared a birthday, 24 November, and a whole lot more besides.

People often ask me who was my favourite cricketer when I was first getting interested in the game. Bearing in mind the way I played, most assumed that I took my lead from somebody like Sir Gary Sobers, the greatest all-rounder I ever saw, or a swashbuckling cavalier like Ted Dexter.

But when I told them Kenny Barrington was my favourite, almost all were nonplussed. Kenny could play. Make no mistake about that.

He scored 20 Test hundreds and nearly 7,000 runs in all, and if you look at the list of those batsmen with the highest Test averages of all time you’ll find K. F. Barrington at number six, with an average of 58.67. To put that in its proper context, of the all-time greats he made his runs at an average higher than Wally Hammond, Sobers, Jack Hobbs, Len Hutton and Denis Compton, and of the modern giants, higher than Sachin Tendulkar, Steve Waugh, Brian Lara and Viv Richards. He could play all right.

The problem for those who assume that someone like me takes their lead from a similar player is the way Kenny generally batted. If you wanted to be kind, you’d call him obdurate. Others, less kind, said that on occasion, watching Kenny grind out the runs was like watching your fingernails grow.

But what I loved about The Colonel, as he was known and revered, was neither the number of runs he made nor the way he made them. It was simply the look of him. Had they made a film of his life, Jack Hawkins would have been perfect for the part. Kenny brushed his teeth like he was going to war. When he marched out to bat, he looked ready to take on an army single-handed. With his great, jutting jaw and hook nose almost touching in front of gritted teeth, the expression on his face said, ‘You’ll never take me alive,’ and it made an impression on the young Botham that deepened as I grew to know him personally in his roles as England selector and later coach.

Before I met Kenny I was actually quite apprehensive about the kind of bloke he might turn out to be. Bearing in mind what he looked like in action, scary was the word that crossed my mind. But it didn’t take me long to realize that although he was ice-cold on the outside, the guy had the warmest heart in cricket. What is more, he was held in exactly the same high regard wherever he went. There wasn’t a dressing room in the world where Kenny wasn’t welcome.

One of the reasons was the humour that went with him; some of it was even intentional. The rest, down to the fact that for years he waged a losing battle with a tongue that simply refused to say what he wanted. ‘Carry on like that,’ he told me once, ‘and you’ll be caught in two-man’s land.’ ‘Bowl to him there,’ he urged, ‘and you’ll have him between the devil and the deep blue, err … sky.’

But he was far more than a figure of fun. In fact, I would go so far as to say that had untimely death not cut short his second career, I believe Kenny would have become a truly great coach. Confidant, technician, helper and motivator; these were his responsibilities as he saw them. And he was excellent at all of them.

The last thing a player wants to hear from a coach is the sentence that begins with the dreaded words: ‘In my day.’ I never once heard him utter them. He was happy enough to talk about the past and his career as a player – and I for one never tired of hearing him recount hitting the mighty Charlie Griffith back over his head for the six with which he reached a century against the West Indies in Trinidad on the 1967–68 tour, his last in Test cricket – but the crucial thing was that he only did so when asked.

The key to Kenny’s success as a coach was that he never spoke down to his players. In later years it became the norm for the coach to adopt a much more authoritarian approach and believe they should ‘run’ the team. Kenny never told anyone to ‘do this’ or ‘do that’; instead, he posed the question: ‘What if you did this?’ or ‘How would you feel about doing that?’, and we responded because we all felt our opinions were being considered.

As a technical coach he was brilliant at spotting little problems and addressing them before they took hold. On my second tour of Australia in 1979–80 he corrected something in my batting that altered the way I played for the rest of my career. I used to take guard on middle-and-leg stumps, then just before the bowler reached the moment of delivery I would move back and across to get right in line. Early in the tour I found I was getting out lbw on a regular basis and couldn’t understand why. The incident that brought things to a head happened in Adelaide, when a South Australian quickie by the name of Wayne Prior won an lbw decision against me with a ball I was convinced was drifting down the leg side.

Kenny saw I was cross when I got back to the dressing room, but when I watched the replay on the television link-up I was amazed to see that I was in fact plumb. Kenny waited until I’d calmed down then quietly took me to one side and suggested we have ten minutes with the bowling machine in the nets. That was all it took. He spotted that I was moving too far across my stumps before the bowler let go, so that balls I thought were going to miss the leg stump were actually hitting about middle and leg.

‘Try taking leg stump guard,’ he said, and for the rest of my career, apart from when specific situations demanded otherwise, I did.

He became a massive influence on me personally. Which is why his sudden death during the Barbados Test on the 1980–81 tour of the West Indies hit so hard. When I took the phone call from A. C. Smith, our manager, I just didn’t want to believe what he was telling me – that Kenny had suffered a heart attack in the night. My immediate reaction was that we shouldn’t play the next day’s cricket, but after a team meeting to discuss what we should do, it soon became clear that the only thing to do was to carry on, for Ken.

I have often wondered how my career and my life might have been different if Kenny had been around to guide me. Regrets, I’ve had a few, etc. But there were times, particularly following the amazing triumphs of 1981, that I allowed success to go to my head and in what came to be known as the ‘sex, drugs and rock’n’roll’ days of the mid-80s. Would Kenny have been a sobering influence when I needed one? Many friends of mine believe Kenny was taken at the very time I needed someone like him to make me see sense. All I know is that I missed him terribly.