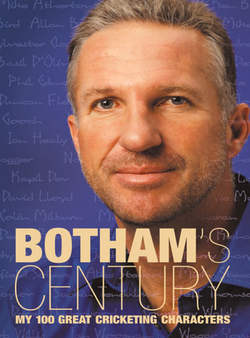

Читать книгу Botham’s Century: My 100 great cricketing characters - Ian Botham, Ian Botham - Страница 21

Sylvester Clarke

ОглавлениеAnyone who knew Sylvester Clarke knows there never were truer words spoken than his entry in the Cricketers’ Who’s Who, next to the section entitled ‘Relaxations’. It comprised precisely two words: ‘music’ and ‘parties’.

You’ll understand, then, why although on the field I rated a meeting with the Surrey and Barbados monster-quickie several places behind sitting naked in a bucket of wasps, I looked forward to the après-cricket with this guy more than almost anyone else.

On one occasion, things might even have got a shade out of hand, although, in my defence I only ever had the interests of my team-mates at heart. The place was Weston-super-Mare; the event, a county championship match between Somerset and Surrey in the early 1980s; and the result, carnage. The pitch at Weston used to be lively at the best of times. Sylvester Clarke, menacing and almost perversely keen on his work, represented the worst of times. We had won the toss and fielded first on day one. Day two meant us against the Beast on a flyer. Enter Vic Marks, my wily Somerset team-mate with a cunning plan.

‘Beef,’ chuckled Vic. ‘Any chance of you having a little drink with Sylvers tonight?’

Thus a convivial pint in the sponsor’s tent wandered into a second, a third meandered into a fourth, and by then Botham and Clarke were in love with each other and the world. ‘I know,’ piped up someone whose voice sounded strangely like Vic’s, ‘What about a drinking contest, lads? Somerset v Surrey, Beefy against Sylvers?’

And so my double-vodka and rum was matched by his double-rum and vodka. My half-pint of gin and campari was matched by his half-pint of campari and gin until by the time we got back to the hotel the only thing holding us up were the fumes we kept breathing into each other’s faces. Kids, do not try this at home. In fact, do not try it at all. The last thing I recall was the sight of probably the most fearsome fast bowler alive, dead to the world laid out unconscious on the pool table and snoring like a walrus.

The next time I saw him I passed him on my way out to bat. He didn’t look well, and he sounded worse.

‘Beefie, mahn … Beefie, mahn. What have you done to me … Beefie Mahn?’

‘All in a night’s work,’ I told him.

No idea what happened in the game. By then, the result was incidental.

Even from a safe distance, for those of us who enjoyed watching great, fiery fast bowling, watching Clarke bowl was a terrifying experience. What struck you was the ambling, rolling gait of around seven paces with which he sauntered to the crease, like a Western gunslinger walking through the doors of the saloon, come to fill some varmint full of lead. The gunshot came from absolutely nowhere. One arm up, the other driven by a right shoulder that seemed about twice the size of his left, through the delivery before you could blink. And the resulting high-climbing missile was almost always unerringly straight. He was simply a terrific bowler; in his day, I believe, the quickest in the world. In any other era, he would have strolled into the West Indies team. It was just his misfortune to be operating at the same time as Malcolm Marshall, Joel Garner, Andy Roberts, Michael Holding and Colin Croft.

But in county cricket Sylvers was something else, so much so that every time Surrey played at the Oval there were two games in progress simultaneously. The first when Sylvers was not bowling, when the flat, pacey but even-bouncing decks prepared by Harry Brind looked absolutely jam-packed with runs. The other, when Sylvester came on to bowl. Be afraid. Be very afraid.

For a guy who inspired so much apprehension and caused so many niggling injuries to flare up on the eve of a trip to Surrey, mainly in batsmen I seem to recall, the wave of sadness that washed over the game when Sylvester died stupidly young indicated in just how much affection the Bajan was held. For lovers of cricket in Barbados particularly, to lose Sylvers and Malcolm Marshall in such a short space of time must have been difficult to bear.