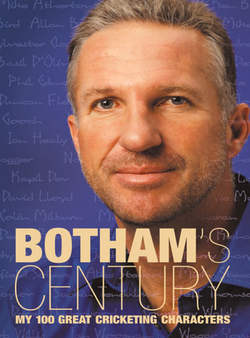

Читать книгу Botham’s Century: My 100 great cricketing characters - Ian Botham, Ian Botham - Страница 19

Laurie Brown

ОглавлениеLaurie Brown played as significant a role as anyone in England retaining the Ashes in Australia in 1986–87. His name may not be overly familiar to cricket buffs, but Laurie was the England physio at the time. We were the side that had only three things wrong with it: ‘They can’t bat, can’t bowl and can’t field.’ Step forward, Martin Johnson, then on The Independent and now with The Daily Telegraph. I made sure his drinks bill got a hammering after we won the opening Test at the Gabba, especially as I managed to make what turned out to be my last century for England there. I was less happy following the second Test in Perth, after damaging an intercostal muscle. That’s basically a rib injury, which affects most bowlers at some time in their career; it’s one of the most frustrating because it takes its own time to heal and simply cannot be rushed.

I was very depressed because I knew this was a bad strain. Laurie confirmed that. ‘You’ve done a good job there, Ian. This could take eight weeks to clear.’ Waiting on the sidelines for the remainder of the tour was not in my game plan. I gave Laurie one of my special hugs and informed him gently that we could do better than that. Laurie realized this was not a time to argue, and just nodded. He was brilliant. I can’t remember if we had any other injury problems at the time, but other patients hardly got a look in. We had up to half-a-dozen sessions a day, and I always had the last appointment. That’s when a bottle of Scotch would appear out of a drawer or out of my cricket coffin. Laurie was a Scot. He played rugby on the wing for Musselburgh, and he certainly enjoyed a dram. Every night we went through the same ritual after three fingers of the liquid gold were poured out.

‘Do you want any water with that?’ I would ask.

‘Water … water. There’s enough water in there already,’ was the consistent answer.

Whatever the reasons, these intensive sessions worked. As well as all the ultra-sound treatment and various rubs, I would be in the swimming pool for a couple of hours a day. I only missed one Test, the third in Adelaide, and was declared fit to play after a month, just in time for the Boxing Day Test in Melbourne. England were still leading 1–0 in the Ashes series with two to play. ‘Fit to play’ was rather a loose term. I was about 75 per cent fit, but Laurie and I reckoned that was about as good as it was going to get in the time available. That was just as well, because my opening partner, Graham Dilley dropped out on the morning of the MCG Test and was replaced by Gladstone Small. In the end, ‘Stoney’ and I took five wickets apiece, and the Ashes were retained by an innings inside three days. I would never have made it without Laurie’s time and consideration.

All physios play the Father Confessor role to cricketers to some extent – there’s a strong and strange bond because you rely on them so much – but Laurie held a special place among England players during my time. The physio hears all sorts of things from players lying on the treatment couch. It’s not only physical grumbles that cricketers want reassurance about. The bottom line is trust. You have to trust that the physio’s solution to an injury problem is the right one. The best physios are the ones who don’t bullshit when out of their depth or dealing with a problem outside their area of expertise. Injuries and strains do seem to be more difficult to diagnose these days, even with all that sophisticated machinery. The good physios are the ones who refer you immediately to an expert consultant or clinic, and are not too proud to admit they don’t know the answer. Laurie was one of the good ones.

Finding a specialist abroad can be difficult and you are often taken to specialists on recommendation. Sometimes you strike lucky, as when Graham Gooch was suffering from a finger infection during the 1990–91 Ashes tour. Laurie soon realized the problem was too tricky for him to solve and within hours of sending him to see the surgeon, Randall Sach, Goochie was under the knife. This quick action probably saved him from losing his hand. On other occasions, cracks and fractures have not been picked up on X-rays. By the time of the 1992 World Cup, Laurie was as familiar with my creaking body as I was. Back, shoulders, knees and ankles had all been heavily strapped at various times. Laurie said that as soon as he bandaged me in one place, it would force the trouble to emerge somewhere else. He was convinced there was going to be a day of reckoning – when some part of me would just explode. Laurie’s hope was that he wouldn’t be around when it happened.

There was a price to pay for Laurie’s friendship and assistance. That price concerns a football team from the Unibond Premier League called Stalybridge Celtic. Laurie lived next door to the ground and had a seemingly interminable supply of stories. If I were ever to go on Mastermind – stop chortling at the back there – that bloomin’ club would be my specialist subject. For years and years, Laurie boasted proudly that Stalybridge were on their way up. I’ve waited and waited, but, astonishingly, as yet local rivals Manchester United haven’t been threatened.

Laurie was the daddy to the team in my time. He was a generation older than most of the lads, and had been around a bit. When we sought advice, it was offered in that gentle Scottish accent and with that canny way of his. He was always available for a chat. Even I didn’t want to go out every night, and Laurie never complained about me or anyone else invading his room for an evening of philosophizing or talking nonsense. He put his life, as well as his career, on the line with me during the 1992 World Cup. He was the management’s sacrificial lamb when I wanted a night out. They reasoned that, unlike any of my colleagues, Laurie and his health were expendable. Not as far as I was concerned.