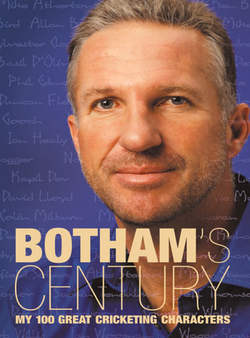

Читать книгу Botham’s Century: My 100 great cricketing characters - Ian Botham, Ian Botham - Страница 25

Hansie Cronje

ОглавлениеIf I bumped into Hansie Cronje tomorrow, there is only one word I can think of saying to him – apart from the obvious smattering of Anglo-Saxon vernacular – after his conversion from a sporting statesman who led South Africa out of apartheid’s shadows to become a two-faced, two-bob cheat: ‘Why?’ We may never know what possessed Cronje to fall into the clutches of bookmakers and become a willing stooge for match-fixers. Nor am I convinced that the full story of his duplicity, deceit and double standards came out at Judge Edwin King’s commission of inquiry in South Africa. But one thing is certain: Cronje will go down in history as a devious charlatan who sold cricket’s reputation for sportsmanship and fair play down the river.

Why did you do it, Hansie? Why, why, why?

I was as shocked as everyone else when he was sacked as South African captain on 11 April 2000 because he was just about the last person on earth you would suspect of making squalid pacts with the underworld.

Everyone young enough to remember the autumn of 1963 recalls where they were and what they were doing when US President John F. Kennedy was assassinated; and I will always remember being on my way to a Pride of Britain awards lunch in Park Lane when news of Cronje’s downfall broke. I was gobsmacked, absolutely dumbstruck.

The previous weekend, Indian police had announced they had tapes of Cronje’s mobile-phone conversations with a bookmaker – which they stumbled across pursuing an unconnected murder inquiry – and most people had treated their revelations with a cellar, never mind a pinch, of salt. The allegations seemed to lose credibility when a respected South African journalist, Trevor Chesterfield, claimed he had heard the ‘incriminating’ tapes – and that neither of the voices was Cronje’s. Little did he know that the tapes were merely re-enactments of the transcripts, and the voices he heard were those of Indian actors.

Four days later, the dreadful truth was out. Cronje, having lied to his employers about any involvement in dodgy deals with bookmakers, spilled the beans to a clergyman before telephoning Dr Ali Bacher, managing director of the United Cricket Board, at three in the morning.

You have to ask whether any sportsman, alive or dead, has ever fallen from grace so suddenly – and so far. Ben Johnson, who won the 1988 Seoul Olympics 100 metres in a world-record time before he was exposed as a drugs cheat, comes close. But from being a South African sporting pin-up – a God-fearing, clean-cut, successful captain of his country, revered by fans and sponsors – Cronje was suddenly despised worldwide. And he gets no sympathy from me.

When you consider how long South Africa had spent in the doldrums because of apartheid, and the giant strides they had made in the eight years since being readmitted to sport’s mainstream, it must have been a crushing blow to their national pride. In 1994, when Kepler Wessels led them to victory at Lord’s, and when Francois Pienaar accepted the rugby World Cup from President Mandela a year later, South Africa had regained the respect lost over 25 years of blinkered politics. At a stroke, Cronje’s greed dispersed that pride and replaced it with dark clouds of shame. What a waste – under his leadership, South Africa had emerged as the likeliest challengers to Australia’s domination of Test cricket, and it seemed inevitable that they would have employed him in a coaching or managerial capacity when his playing days were over.

Now he’s been banned for life from all forms of cricket. In the summer of 2001, he was even barred from making an after-dinner speech at a benefit function for his old Free State team-mate Gerhardus Liebenberg – and I’m not surprised. I wouldn’t want him to open my local school fête.

It still sickens me when I think of the way I applauded his decision to forfeit an innings at the Centurion Test against England 17 months earlier. At the time, like most people, I thought it was a wonderful gesture by Cronje to make a game of it for the spectators after three days had been wiped out by rain and condemned the match to a certain draw. I wrote in my column for the Mirror that Cronje’s foresight was a great step forward for cricket, only to discover later that he had been following an altogether more devious agenda which was nothing to do with sportsmanship, and everything to do with lining his own pockets.

While England, unsuspecting accessories to the sting, had every right to celebrate their two-wicket win, I felt I’d been duped, conned and cheated when the truth came out. Cronje had not horse-traded and contrived a tight finish for the good of the game, but for a £5,000 backhander and a leather jacket from some bookmaker who stood to lose a fortune if the game petered out into a draw. Mike Atherton said at the time it felt like the cheapest Test win of his career, and now we know why. At the King Commission, more sordid details emerged about Cronje’s attempts to draw vulnerable team-mates into his web of deceit. Picking on Herschelle Gibbs, a Cape-coloured batsman, as a target for his scheming was particularly loathsome.

In effect, Cronje now lives in exile among his own people. He has to rebuild his life, if he can, knowing the cricket community worldwide despises him. I could go on to say what a fine batsman, and respected captain, he was – but who cares now? Nobody will remember him for those things any more.