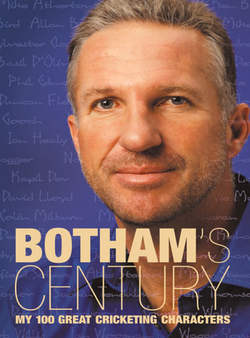

Читать книгу Botham’s Century: My 100 great cricketing characters - Ian Botham, Ian Botham - Страница 22

Brian Close

ОглавлениеAnother prize nutter. Is it me, or what? Don’t answer that. It is something of a minor miracle, in fact, that my career lasted beyond my first few matches under Brian Close’s captaincy. It was not that he didn’t think I could play. As time progressed, he convinced me that I could achieve anything I set my mind to. No, the problem was his bloody driving.

I’ve faced the fastest, most hostile bowlers in world cricket, with helmets and without, on minefields as well as shirtfronts. But I never knew what cold fear was until I slipped into the passenger seat of Close’s car.

As young players taking our first steps at Somerset under Brian, and being taught everything we knew by him, guys like myself, Viv Richards, Vic Marks and Peter Roebuck would travel to the ends of the earth for him. The only problem was his preferred mode of transport.

Behind the wheel of whichever beaten-up old banger he was scaring to death at the time, Close’s performances were legendary. On one occasion he picked up a motor from the garage where it had undergone major surgery, turned left, smacked into the back of a van, went around the next roundabout and drove it straight back in for repair again.

I will never forget my first experience of Close’s unique driving style; the first thing that hit you was his need for speed. Come shine or rain, day or night, crystal-clear visibility or pea-soup fog, to him all driving conditions were perfect for cruising at around 100 mph. The next thing you noticed was the open flask of scalding hot coffee pirouetting on the central console. Then there were the beef sandwiches made for him by his wife Vivian, which, while steering the car with his knees and with seemingly little regard for what was happening on the other side of the windscreen, he would open up with both hands to make sure the meat content was acceptably high. And finally, to complete this nightmarish scene, he had a copy of The Sporting Life, folded in half on his lap, from which I swear he was studying the form as he drove along.

‘Do you want me to drive?’ I would ask, hopefully. His reply every time? ‘No, lad. Driving helps me relax.’

People who didn’t know Closey used to recount the stories of his exploits in the field in tones of hushed amazement. Those of us who knew him took no persuading whatsoever to believe every single word.

His speciality as a fielder was to use himself as a human shield. He reasoned that a cricket ball couldn’t possibly hurt you because it wasn’t on you long enough. And he lived and nearly died by that principle in suicide positions all round the bat, particularly at the shortest of short square leg. Once, fielding in that spot, the ball rebounded from his forehead towards second slip.

‘Catch it!’ he shouted.

After the ball was taken, his team-mates raced towards the stricken Closey to make sure he was okay.

‘I’m fine,’ he assured them.

‘Yes, but what if the ball had hit you an inch lower?’ one of them asked.

‘Well, lad. He’d have been caught in the gully,’ said Closey.

Gary Sobers was another who fell victim to Closey’s awesome (some might say foolhardy) disregard for personal well-being, in the 1970 Test at the Oval between England and the Rest of the World. On a featherbed pitch, the best hooker in world cricket was playing John Snow with a stick of rhubarb. Only a madman would have put himself so close at forward short leg. Say no more.

The inevitable moment arrived; Snow bowled a short one, Sobers rocked back and prepared to lever the ball into the middle of the Harleyford Road. Any other cricketer would have hit the deck and hoped for the best. Closey didn’t budge an inch. In the event, Sobers was a fraction too early with the shot, and as everyone else in the ground prepared to trace the flight of the ball over the perimeter wall with the fielder’s head attached to it, Close kept his eyes open and on the ball that travelled from the bottom edge of the bat to the batsman’s hip and into his hands for the catch.

There could be no more graphic proof of his bravery than his performance against a fearsome West Indies pace attack led by Michael Holding in near-darkness on the evening of the third day of the Old Trafford Test of 1976. At 45, 27 years after making his Test debut, Closey had been recalled by skipper Tony Greig to add some experience to the England batting, and some guts too. In a terrifying barrage and without any protective intervention from the umpires, Close and John Edrich took blow after blow on the body. When Close took his shirt off in the dressing room afterwards his chest was covered with black and blue, cricket-ball shaped bruises. ‘Someone take a picture of my medals,’ he urged. Someone did and the resulting photo was one of his most-prized possessions.

A lot of captains talked about leading from the front. With Closey it was more than just talk. He made an art form of it, and I have no hesitation in saying that a lot of what I’ve achieved in the game is down to the principles he drummed into me as a youngster at Somerset. I know that if you asked Viv Richards he would tell you exactly the same.

The first thing he taught us was just how much cricket was played in the mind. Very early in my career at Somerset, when I’d played only a dozen or so matches for the first team, he took me to one side and told me straight out, ‘You should be in the England side.’ Before Viv had even properly established himself in our first team at Taunton Close told him, ‘You are going to be the best batsman in the world.’ And those things rub off. Sure, some might say that such talk could have an adverse effect on a certain type of character. Close’s opinion was that it would only have an adverse effect on the wrong type of character.

For the rest, it was always his intention to instil in you the belief that you were the best. As far as he was concerned, all he needed to say was this: ‘You are better than the bloke at the other end. Now prove it.’ And I recall him saying that to me when I ran in to bowl for the first time to none other than Colin Cowdrey.

Closey retained his total enthusiasm throughout his extraordinary career, and was still leading the Yorkshire Academy XI of promising youngsters well into his sixties. The only two occasions on which I ever saw him anything like flustered had nothing to do with cricket. The first was when I announced that I was going to marry his goddaughter Kathryn Waller when we were both still so young, and the second, at a hotel in Westcliff before a county match against Essex, when I watched him walk straight through a plate-glass sliding-door. It sounded like a bomb had gone off. Miraculously, he escaped with a tiny nick on his hand, just to prove that whether behind a wheel, at madly-close short leg, against Michael Holding’s bouncers in the gloom, or whatever the danger, Closey was a born survivor.