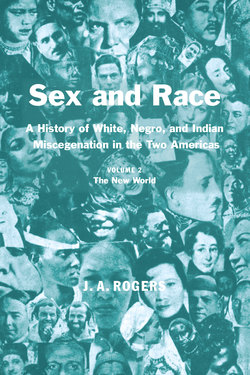

Читать книгу Sex and Race, Volume 2 - J. A. Rogers - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Six

ОглавлениеMEXICO

MISCEGENATION in Mexico differs from other Latin American lands in that most of it seems to have been between the Indian and the Negro. Apparently, the Mexican Indian has been more mixed with Negro than any other group of American aborigines save those of the United States.

There were a considerable number of Negroes at the start. Two hundred of them accompanied Cortez, the conqueror of Mexico in 1519, one of whom, Juan Garrido, was the first to sow and to reap wheat in the New World.1 Other Negroes accompanied De Narvaez, the rival of Cortez the same year.

The Negroes were imported in such numbers that in 1535, or only sixteen years after the conquest, they outnumbered the Spaniards. Priestley says, “Their number was already great enough to be hazardous, there being more Negroes, not counting mulattoes than there were Spaniards in New Spain (Mexico) by the middle of the century.

“Practically every bishopric in New Spain contained more blacks than whites before 1575. In agriculture, Negro labor was of greater utility than that of the Indian. The black man could perform in a day six times as much work as an Indian, and did not suffer from punishment or privation as did the more delicately constituted native.”2

The Negroes continued to arrive until by the end of the same century the slaves alone, according to figures from the Archives of the Indies in Seville, outnumbered the whites and the near-whites, who totalled 17,711 as against 18,569 Negroes.3 This latter figure did not include the free blacks, the mulattoes, and the runaway slaves, whose percentage was large. In Mexico City, itself, the Negro element outnumbered the white and near-white.

The Negro slave and the Indian—who had been reduced to slavery also—made common cause. In 1537 both plotted to capture Mexico City, but one of their number gave the plot away and twenty-four were hanged and quartered.4 Other revolts in 1669 and 1735 were more successful. One led by Yanga, a Negro slave, in Vera Cruz, being especially so. Yanga not only killed many of the white and near-white overlords, but founded a kingdom of his own, which he called Lorenzo.

MIXED PEOPLES OF MEXICO.

XXII. Upper left. Negro-Indian-White woman. The remainder: Zambos, or mixed Indian end Negro. (Charcoal study by Goytia.)

MEXICAN MIXED-BLOODS.

XXIII. Negro-Indian woman. (Charcoal by Goytia.)

There seems to have been a great sexual affinity, too, between the Mexican Indian and the Negro. Bancroft says, “Marriages between Negro men and Indian women were common, the latter preferring Negroes to Indians, and the Negro males being more fond of the Indian women.”5

The Spaniards also had many children by the Indian women. In fact for the next two centuries almost the only feminine company available to the white men were Indians, Negroes, and mixed blood women. White women were always scarce in Mexico. As late as 1803, they constituted less than ten per cent of the total white population. Cortez, himself, took an Indian wife, Marina.

One reason why Negro-Indian matches were popular was that the offspring of such unions were born free. But there were so many of these chinos, as the children were called, that the viceroy asked the king to issue a decree making them slaves. This was denied by the Pope, with whom rested final sanction. The children were called chinos, probably because the mixture accentuated the Mongolian strain which the Indian is said to have.

Von Humboldt, the great naturalist, who travelled much in Mexico in the 1810’s, says that the Indian women preferred the Negro men because the blacks were livelier than their own men. “There exists,” he says, “no contrast more striking than that of the impetuous vivacity of the Negro of the Congo and the apparent phlegm of the coppery Indian. It is especially because of this contrast that the Indian women preferred the Negro not only to the men of their own race but even to the Europeans.”6 As regards the mixed bloods, he says, “One would say that the mixture of the European and the Negro everywhere produces a race of men, more active and more assiduous than the mixture of the white and the Mexican Indian.”

Other travelers of the period noted this difference between the Indian and the Negro, too. Coleridge said, “The amazing contrast between these Indians and the Negro powerfully arrested my attention. Their complexions do not differ so much as their minds and dispositions. In the first, life stagnates; in the last it is tremulous with irritability. The Negroes cannot be silent and they talk in spite of themselves. Every passion acts upon them with strange intensity. Their anger is sudden and furious; their mirth clamorous and excessive, their curiosity, audacious. It is even said that the slaves despise the Indians, and I think it very probable; they are very decidedly inferior as human beings.” The Negroes, he added, welcomed life and adventure while the Indians “shrunk before the approach of other nations as if it were by instinct.”7

MEXICAN MIXED-BLOODS.

XXIV. 1. General Don Louis Cortazar, hero of the war for Mexican independence. 2. and 3. Diego Rivera, world-famous mural painter. The Negroid strain is apparent in both.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, as reported by Humboldt, a large proportion of the Mexican population were chinos. He also cites “the great number of mulattoes, artisans, and free Negroes who by their industry alone, procure much of the necessaries of life.” He gives the number of mulattoes in Mexico City as 7094. That of the chinos at the capital must have been large, too, in proportion to the rest of the population.

The mulattoes increased to such an extent that in 1805 an attempt was made to curb their power by a law forbidding the marriages of whites and blacks. “This open stigma upon a population, numbering nearly half a million,” says Bancroft,” was hardly a popular measure. This population ranked among the most useful in the country. Aware of their superiority they looked down upon the Indians, and were not a little encouraged in this respect by the evident preference accorded them by female aborigines, who were lured by their greater vivacity. It is even said that they preferred them to Europeans.”8

As in Venezuela, Brazil, and elsewhere, a mulatto family in Mexico could have itself declared white and enter the privileged ranks, if it was wealthy enough. Humboldt says, “It often happens that families suspected of being of mixed blood demand from the high court of justice (l’audencia) to have it declared that it belongs to the whites. These declarations are not always corroborated by the judgment of the senses. We have seen swarthy mulattoes who had the address to get themselves whitened (this is the vulgar expression). When the color of the skin is too repugnant to the judgment demanded, the petitioner is content with an expression somewhat problem-matical. The sentence then simply bears that such or such individuals may consider themselves whites. (Que se tengan por blancos.)”9

The most noted Mexican of Negro ancestry is Vicente Guerrero, the William Tell of Mexico, its second president, in whose honor a state is named. Guerrero was an ex-slave, and his first step on coming into power in 1829, was to issue a decree freeing all the Negro and Indian slaves. He wrote into the Mexican Constitution, Article 10:

“1. That slavery be exterminated in the Republic.

“2. Consequently those are free who up to this day have been looked on as slaves.”

By then, however, Negro slavery had almost died out in Mexico, except in one of its states, where it was growing stronger. This was Texas, whither many white Americans had been bringing in their slaves since 1821. These slave-holders opposed President Guerrero’s emancipation decree, and it may be interesting to note that but for the stand of this Negro president against slavery, Texas would almost certainly not now be in the American Union. Texas wanted independence in order to be able to keep its slaves. The constitution of Texas as an independent state was never submitted to the people but was arbitrarily put over by the American slaveholders. John Quincy Adams denounced the fight of the Texan slaveholders for independence, in the House of Representatives, May 25, 1835, saying “it was not for the maintenance of the principles of political and religious liberty but a civil war for the perpetuation of slavery and the slave trade.”

A GEORGE WASHINGTON AND ABRAHAM LINCOLN COMBINED.

XXV. General Vicente Guerrero, second President of Mexico. Freed Mexico from Spain and then liberated the slaves. Had been a slave himself.

As regards Guerrero’s Negro strain, writers and encyclopedias10 of the time say that he was a mulatto, but the present tendency is to deny the Negro part of it and say it was Indian. In 1935, when I said in a newspaper article that Guerrero was a mulatto, some California Mexicans objected indignantly. However, the Lawyers’ Guild of Mexico who was appealed to in 1940 by a Negro organization when the Mexican government tried to bar American Negro tourists, said in its reply that it was most unjust since a Negro, Guerrero, had played such a role in bringing about Mexican independence.11 Guerrero’s less idealized portraits very clearly show his Negro strain. Guerrero’s most trusted aid was a Negro, Colonel Juan del Carmen, who is described by Villasenor as “very black, of unprepossessing appearance, and extraordinary bravery.” Carmen died fighting for Mexican independence.

The first ruler of Mexico, after its independence, Iturbide I, might have had a Negro strain, too. He was “a mestizo of Valladolid, who was generally accepted as a creole,” says Priestley. As was said, the terms mestizo and mulatto were often confused, especially if one’s hair was straight rather than frizzly.

Another noted living Mexican who shows an undoubted Negro strain in features, color, and hair is the great mural painter, Diego Rivera.

With the abolition of slavery and the slave-trade, the number of Negroes in Mexico were so absorbed by the Indians and whites that the strain was hardly longer visible. As Poinsett, American Minister to Mexico in the 1820’s said, “It is, I think, difficult to distinguish the African blood after two crosses with the Indians. They (the mixed bloods) lose entirely the Negro features and the mestizoes have straight black hair like the Indians.”12

However, a close-up of any eastern Mexican community will reveal to the trained eye signs of the old Negro ancestry. This is especially true of the states of Guerrero and Oaxaca; the warm regions of the Gulf as the City of Vera Cruz; and parts of the Pacific coast.

As regards the mixing of Mexicans, and American whites and blacks in northern Mexico, see the chapter on Texas in the section on the United States.

ADDITIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

Luis Querol y Roso, Negros y Mulatos de Nueva Espana de su Alzamiento en Mejico en 1612. Anales de la Univer. de Valencia, Ano 12 Cuad. 90. This article has abundant documentation.

Riva Palacio V. Mexico a traves de los siglos, Vol. 2, 239-41, 1887.

___________

1 Diccionario Universal de Historia y Geographia, Vol. 2, pp. 499-500. 1853.

2 Priestley, H. I., The Mexican Nation, pp. 57, 126. 1923.

3 Toro, A., Influencia de la Raza Negra en la Formacion del Pueblo Mexicano, pp. 215-18, in Ethnos, Vol. 1, Apr. 1920-March, 1921.

4 Bancroft, H. H., History of Mexico, Vol. 2, p. 385. 1883.

5 Bancroft, ibid., Vol. 2, p. 772.

6 Humboldt, A., La Nouvelle Espagne, Vol. 1. pp. 407-08. 1811. Also the English translation: Kingdom of New Spain, Vol. 1, p. 234. 1811.

7 Coleridge, H. N., Six Months in the West Indies, pp. 84-5. 1826. This view of the Indian character was general. Chanvalon, who visited the French West Indies in the 1760’s and saw the Carib Indians, said in like vein, “Nothing equals their stupidity. Their reasoning powers are very dull and are endowed with hardly more foresight than the instinct of animals. While the intellect of the clumsiest European laborer, and even that of the Negroes in the most benighted regions of Africa, appears to be clouded, it is nevertheless capable of being enlarged but that of the Carib does not seem susceptible of this.” (Voyage a la Martinique, p. 51. 1763.)

Las Casas, their great protector, said similarly, “All these people are naturally simple; they know not what belongs to policy and address; to trick and artifice… They are a weak, effeminate people, not capable of enduring great fatigue… . The Almighty seems to have endowed them with meekness and a softness of humor like that of the lambs.” (An Account of the First Voyages and Discoveries, etc., pp. 2-3, 1699.

8 Bancroft. H. H., History of Mexico. Vol. 3, p. 753. 1883.

9 Humboldt, A., Kingdom of New Spain, pp. 246-7. 1811.

10 Larousse, Vol. 18, p. 65, 1872; Biographie Universelle, Vol. 8, p. 1603, 1857; Anti-Slavery Almanac—article reproduced in Colored American, Sept. 5, 1840.

11 Letter to the West Indies National Council of New York, published in the Negro Press, Oct. 10, 1940.

12 Poinsett, J. R., Notes on Mexico, p. 185. 1825.