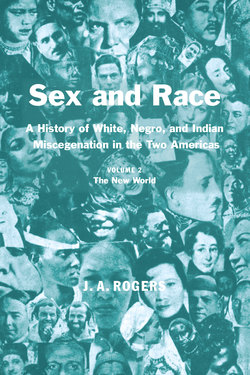

Читать книгу Sex and Race, Volume 2 - J. A. Rogers - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Eight

ОглавлениеTHE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

IF Haiti is the Negro republic then Santo Domingo is the mulatto one. Originally called Hispaniola, together with Haiti, it is the oldest European settlement in the New World, its capital San Domingo, now called Trujillo City, having been founded by Bartholomew Columbus, brother of the navigator, in 1496.

At its discovery, the island was well populated, the number of its inhabitants having been set down at from two to three millions, which is evidently an exaggeration. What is certain, however, is that by 1542, fifty years later, the Indian population had shrunk to a few thousands. The Indians refused to toil for the Spaniards—in fact they seemed unable to grasp the idea of working for the enrichment of others—with the result that they were treated with a barbarity unparalleled in history. Las Casas, Bishop of the Indies, witnessed these cruelties and wrote an account of them.

To take the place of the vanishing Indian, the Negroes were brought in in 1502, and despite the cruelties and the hardships throve so well that Herrera, a historian of the times, said that Hispaniola was not long in becoming another Guinea in the color of its population.

In the Negroes, too, the Spaniards found an entirely different customer from the Indian. Although care had been taken to take the Negroes from the different tribes and so mix them so that they could not understand one another’s language, when subjected to ill-treatment, they fought back. In 1522, or only twenty years after their introduction, they revolted in Santo Domingo City and killed six Spaniards, and wounded several more. Diego, son of Columbus, and governor of the colony, saved his life, only by flight.1

Negroes did even more: they absorbed the Spaniards until it became almost a black colony.

In time Santo Domingo became the most liberal colony in the New World towards Negroes with the mildest slave laws. But strange to say, it was not law, but lawlessness, that helped most in bringing this about.

This liberal influence was piracy. Off the coast, and not far away was the island of Tortuga, chief buccaneer settlement of the New World. The pirates, who were chiefly English and French, with some Spaniards and Dutch, were interested not in color or race, but in one’s courage and fighting ability. Some of the Negroes as the Ashantis, Dahomevans, and Coroman tees, who were natural born warriors, possessed just the qualities the pirates were looking for, and they welcomed all the runaway slaves and others they could get until a considerable proportion of their numbers were blacks.

CITIZENS Of THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC.

XXIX. Army doctors of the Dominican Republic. (Album de Oro de la Republica Dominicana.)

Several of the best pirate captains as Roc Brasiliano and Diaguillo, protege of Sir Francis Drake, were blacks. Bartholomew Roberts, the greatest of them all, is described by Captain Charles Johnson, another pirate, as “a tall, black man, near forty years of age.”2 Roberts was born in England where Negro slavery then existed. In Tom Cringle’s Log, also, the pirate chief in charge of white men is a coal-black Negro born in Scotland and speaking with a Scotch accent.3

On Tortuga, white, black, and Indian mated freely, producing a mixed brood. The women captured by the pirates and brought to the island were of all races, but chiefly Indian and Negro, and these regardless of color, fell by lot to the common pirates after the captain had taken his pick.

Alexander Esquemelin, who lived among them, and whose book is the standard one on buccaneering, gives an idea of what went on in the pirate settlements when he says, “The Spaniards love better the Negro women in those western parts, or the tawny Indian females, when as peradventure, the Negroes and Indians have a greater inclination to white women, or those that come near them, the tawny, than their own.”4

What was true of Tortuga was also true of the other pirate colonies as Port Royal, Jamaica; Port Royal and Cape Fear in the Carolinas; and Santa Catalina and Nassau in the Bahamas.

Being so near to Hispaniola, the buccaneers practically dominated it until near the latter part of the seventeenth century when Spanish rule was reestablished again; but the racial freedom established by the influence of the pirates remained.

Moreau de St. Mery wrote, “The prejudice with respect to color so powerful among other nations, where it fixes a bar between the whites and the freed people and their descendants is almost unknown in the Spanish part of St. Domingue. Masters were allowed to leave their property freely to their mulatto children.

“It is true and even strictly so that the major part of the Spanish colonists are a mixed race; this is an African feature… .”

Mulattoes were admitted to the priesthood and other posts of equality but unmixed blacks were barred. “The Spaniards,” he said “have not yet brought themselves to make Negro priests and bishops like the Portuguese.”5

Rainsford gives the population in the early eighteenth century as about 40,000 whites, 24,000 free Negroes, and 500,000 slaves, and adds, “Associating in common with, their female slaves, they propagated a people of almost every grade of color and became entirely a mixed colony in which Spaniards formed in fact a very small part.”6 However, as St. Mery says there were certain old Spanish families who shunned any alliances with Negroes and mixed bloods.

As regards the mulatto nature of the colony, a white American resident of Hayti, wrote, “The former Spanish colony of St. Domingo, now called the Dominican Republic, has, for more than a century been virtually a nation of mulattoes. In this colony large importations of slaves soon ceased, the attention of the Spaniards being drawn to their settlements on the Continent, and from the days of slavery, prejudice against color was less strong, and the dispositions of manumitting slaves were very much greater than in the neighboring French colony. Domestic relations on equal terms began early to be established between the whites and the mulattoes. The colonial laws enacted shortly after the introduction of slavery which forbade free people of color to hold offices were soon disregarded. Negroes became registrars, notaries, and priests… .

“Madion puts down the mixed race of the Spanish part at the commencement of the French Revolution at eleven-twelfths of the whole population… . The increased intercourse of the inhabitants with the Haytiens during the first forty years of the century, has deepened the complexion of the Dominicans, and they are now emphatically a nation of mulattoes.”7

Later, Santo Domingo became a part of Haiti, having been annexed by President Boyer in 1822. It recovered its independence in 1844. Perhaps everyone of its presidents was of mixed blood. The most noted mulatto ruler was Baez, who dominated affairs during the greater part of twenty-two years. The most spectacular of all the Dominican presidents was a full-blooded black, Ulises Hereaux.

The great bulk of the population is still mulatto. But it is said that the Dominicans love to think themselves a white people. M. W. Williams says, “The predominant blood in the population is Spanish though almost all have an African strain. There is no color-line but the Dominicans like to be thought of as a white nation, and in their immigration laws they favor the coming of the Caucasians.”8 This, however, is not the sentiment of the greatest man in the republic—the one who has done the most for its stabilization and development: former President Rafael Trujillo. John Gunther who met Trujillo says he “is a mulatto and proud of it.”9

FOREMOST CITIZEN OF THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC.

XXX. Generalissimo Dr. Rafael Trujillo Molino, former President.

Since the Hitler regime, thousands of German refugees, principally Jews, have been brought in as settlers by former President Trujillo. In the Samana district and elsewhere are also the descendants of thousands of American Negroes who settled there during the rule of President Boyer.10

___________

1 Oviedo, Historia Generale de las Indias, Pt. 1. Chap. 4.

2 Johnson, C., Story of the Pirates, Vol. 2, p. 49. Reprinted from the 1725 ed. 1927.

3 Scott, .M., Tom Cringle’s Log, pp. 110-17. 1874.

4 Exquemelin, A., Buccaneers of America, 1684-5, pp. 25-6. Reprinted from the 1684 ed., 1923.

5 Moreau de St. Mery, The Spanish Part of St. Domingo, p. 57. 1796. Trans, by Cobbett.

6 Rainsford, M., Black Empire of Hayti, p. 37. 1805.

7 Remarks on Haiti as a Place of Settlement for Afric-Americans, p. 29. 1860.

8 Williams. M. W., People and Politics of Latin America, p. 390. 1938.

9 Gunther, J., Inside Latin America, p. 441. 1941.

10 Schnenrich. O., Santo Domingo, pp. 472. 170, 171, 263. 1918.