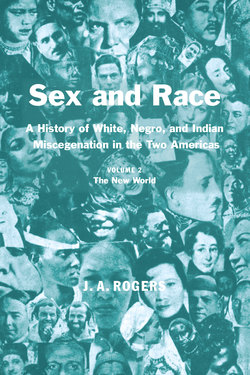

Читать книгу Sex and Race, Volume 2 - J. A. Rogers - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Nine

ОглавлениеHAITI, MARTINIQUE, GUADELOUPE

RACE-MIXING in Haiti began in an enlightened and liberal manner for the times. France, although it had bowed to the evils of Negro slavery, had sets its face religiously against concubinage and illegitimacy. In 1685, it had issued from Versailles, under the seal of Louis XIV, a series of laws for the French colonies, known as the Black Code, Article Nine of which not only fixed a severe penalty on the illicit association of white men and Negro women but provided for the legal marriage of black and white and the legitimizing and the freedom of the mulatto offspring. The article read:

“Free men who will have one or several children through concubinage with their slaves, together with the masters who permitted them, shall each be condemned to a fine of 2000 lbs. of sugar, and if they are masters of the slaves by whom they have had the said children, they should in addition to the fine be deprived of the slave and the children, who should be given to the hospital without ever being able to be free. However when a free man who was not married to another person during concubinage with his slave will marry said slave according to the rites of the church, the slave shall be free by this means and the children made free and legitimate.”1

Accordingly when France took over the eastern part of Hispaniola, or Santo Domingo, now Haiti, from the Spaniards in the latter part of the seventeenth century, this most liberal provision that had yet been made in any colony became a law for Haiti, also. But its observance was almost nil. Marriage with black women, yes—the French from the earliest times had a predilection for black women, and some of those in the colonies actually had black wives; but the freeing of the mulatto offspring was another thing: that was loss of property. The law, furthermore, confined the master and other white men to only one woman, in this case incidentally a black woman, and such a law had never worked in all history. What was even worse economically: it limited the number of mulattoes possible to be born in the colony. Mulattoes fetched a higher price than blacks; and comely mulatto girls were eagerly sought. The result was that colonial life went on its accustomed way, law or no law. France and the French king and clergy were far away, and the enforcement of the law was in the hands of those whose interests it was to break it.

MIXED BLOODS OF HAITI.

XXXI. Quadroon ladles of eighteenth century, Haiti.

However, much liberality remained as there were white men who loved their black wives and mulatto children. The latter had, under the law the same rights as white people, and at first were granted most of them.

The colony prospered, thanks to the labor of the blacks. In August, 1670, Louis XIV, in a decree authorizing the bringing in of yet more slaves, had said, “There is nothing which contributes so much to the growth of the colony and the exploitation of its natural wealth as the laborious work of the Negro.”2 The soil was exceedingly rich; there was a great demand in Europe for sugar, cotton, and tobacco, and commerce was so good that St. Domingue became the second richest colony in the New World.

Its fame as an El Dorado spread throughout France. White adventurers, many of whom were impoverished aristocrats and the younger sons of peers, flocked out in search of fortune. Other aristocrats, tired of the emptiness of life at the French court, came out, too, in search of mental rejuvenation. Included, also, were white women of the upper-class, who, now that life had become safer, came in the hope of getting a rich husband.

Soon an aristocracy based on the old French model arose. The lower-class whites, or petits blancs, also formed their own caste. These two parasitic elements, saw, as usual, that they could enjoy leisure and luxury only by having a still lower caste to produce for them. In France, it had been other white people, but here, in the tropics, nature had been most kind: It had provided a caste specially colored—a caste that could be kept separate as long as its hue lasted, and so they established what did not exist in France, what had never existed in France, a color-line—a rigid color line—a contempt, outward at least for any mixture, or reported mixture, of African strain. Hilliard d’Auberteuil expressed the spirit of the times when he said, “Policy and safety require that we crush the race of blacks by a contempt so great that whoever descends from it even to the sixth generation shall be covered with an indelible stain.”

The result was that in 1724, the provision in the Black Code which permitted a master to marry his black slave, was annulled. It now read, “Article VI. We forbid our white subjects of either sex to contract marriages with the blacks under penalty.”3

In 1749 and 1763, another influx of aristocrats arrived in Haiti, bringing about such a tightening of the color line that it exceeded that of Virginia and the Carolinas.

The discrimination continued. In January 1767, an order which had already been in vogue in Martinique was sent to the governor of St. Domingue, the purpose of which was to create a distinct line of demarcation in social circles: the aristocrat born in the mother country was to have a superior status to the one of mixed blood born in the colony. This order read, “His Majesty having already excluded those who are descended from a Negro race of any species from all public functions in the colonies, he has excluded them with even stronger reason from the nobility and you ought to be scrupulously attentive to learn the origin of those who will present to you their titles to be registered.”

On May 27, 1771, came an even stronger decree to the governor to do nothing that would “weaken the state of humiliation attached to such noblemen having Negro ancestry in any degree,” and that “under no pretext whatever was the marriage of whites and mulatto women to be favored.” One marquis, who had married a Negro girl in France was informed that he could no longer serve as captain of dragoons. In 1777, the French king sent the following message through the Count de Nolivos, “Noblemen who are descended in any degree whatever from a woman of color can no longer enjoy the prerogatives of nobility. The law is hard but wise and necessary in a country where there are fifteen slaves to one white. One cannot place too great a distance between white and black.”4

Striking out still further against the mixed bloods, the king, on the advice of his councillors, “forbade all his white subjects of both sexes to marry blacks, mulattoes, or other colored people … and that no licenses for same should be issued under penalty.” White parents could no longer leave their money and lands to their colored children.

At these and other restrictions numbers of white men sold their estates and returned to France with their colored wives and children. But even there the Haitian slaveholders pursued them. They caused several anti-Negro laws, hitherto unknown in France, to be passed, one of which forbade “the marriage of Negroes and white women which had been strongly encouraged since 1716.”5 This was in 1763. In 1777 another law forbade all mulattoes and blacks, slave or free, to enter France at all.

In 1768, mulattoes who were officers in the militia had their commissions taken away. A law of the governor-general, June 30, 1762, had already decreed jim-crow regiments for the rank and file. It read: “Nature having established three different classes of human beings: whites, near-whites, and mulattoes or free Negroes, this difference will always be observed in the composition of the militia and under no pretext or denomination must the different species be mixed.”6

Not yet satisfied, the whites determined to pursue the color-line to its limit. In the colony were a number of mixed-bloods, some of them indistinguishable from white, who had been made “white” by law. The next step was to proceed against these by refusing to associate with them and snubbing them whenever possible. To be an officer in the militia was then one of the highest honors, and such “whites-by-law” who were officers were refused places of command in the white militia even though they were the sons of noblemen. Vassiere says, “Le Sieur Baldy was refused a place of command at Port-au-Prince because his maternal grandfather had married a Negro woman; another was refused Sieur de Brethon because he had married Marie Roumat, whose grandmother was a Negro woman of Madagascar.

FAMOUS MIXED BLOODS OF THE FRENCH WEST INDIES.

XXXII. 1. General J. C. Dugommier (1736-1794), Martinique, great Napoleonic commander. 3. General Alexander Petion, first President of Haiti. 2. General Andre Rigaud, valiant leader of the mulattoes in the struggle against the whites. 4. General Boyer, ruler of Haiti during its “Golden Age,” and who brought the whole Island under his rule.

‘The Sieur Chapuzet was barred from a command in the militia because his great-great-grandmother had been a Negro woman. Some enemies of his who didn’t want him into the militia dug into the parish registers and found that one of his ancestors in 1624 was a Negro woman. He claimed that she was an Indian. But the government did not declare him wholly white because of the large number of citizens who were in the same boat and wanted the same consideration.”7

Determined to humble the mixed-bloods still further, some of whom were very wealthy, the white plantation owners went on to enact laws against all of Negro ancestry that could be paralleled only by the caste system of ancient India. Among the things they were forbidden to do were: Not to use any French name or surname for their children but only African ones, under heavy penalty—those having such names were given three months in which to change them; not to wear the same color of clothing as white people nor to be as richly dressed—those who wore jewelry in public ran the risk of losing them; and not to dress their hair in the same style as white people. If a free mulatto struck a white man for any reason he was to be whipped, branded, and sold into slavery.8

As for the illegitimate free mulattoes, the provision in the Black Code which had been made for the protection of mixed-bloods, was used against them and they were seized and sold as slaves. If such had property left them by their white fathers it was seized and given to a white next of kin.

Not in any part of the New World, not even in the Southern States at their very worst, were laws so drastic passed against Negroes or any other people. However, retribution the most awful was to overtake the whites, innocent and guilty alike.

The Negroes, too feebly armed then to revolt openly, resorted to a powerful secret weapon: poison, in the use of which they had been skilled in Africa. Scores of whites, young and old, male and female, died in great agony and their cattle with them. The Negroes, when caught, were burnt alive, inch by inch. In 1777, one of them, Jacques, was burnt alive for poisoning his master and one hundred head of cattle.

To bolster up these cruel laws against the blacks, an attempt was made to increase the white population by bringing in white labor. . This ended in disastrous failure. In 1764, three thousand two hundred and eighty-eight whites were imported of whom 2470 were German, 418 Acadians of Nova Scotia, and the remainder French. Of these 2370 died in one year, 531 returned home, with only 387 remaining. Of 7535 white soldiers also brought out, 75 per cent died in four years.9 On the other hand of 550 free black and mulatto soldiers “only three died in two years.” It became clear that the experiment of white labor would not work.

One governor, Count d’Estaing, realizing that the whites could not retain their power without the support of the mixed-bloods, or gens de couleur, proposed to lift the restrictions from the quadroons and octoroons, “eager enemies of the blacks,” but the king rejected the proposal. The color line should be absolute, he said.

This brings us to the question: Why was an absolute color line needed, and who were the most eager supporters of it? Answer: The white women. Yes, and they had abundant cause for complaint. Neglect was their lot; they were but so many castaways in the lap of luxury. Partly because of the greater sex appeal of the colored women to the white men; the climate of the colony was hard for white women; and partly because in concubinage the white man had little or no responsibility, the white woman had a most difficult time in getting a husband or even any sex attention. Hilliard d‘Auberteuil wrote in 1777, “Marriages are rare in St. Domingue.” Mothers who had brought their daughters to the colony in the hope of getting a rich husband for them arrived to find a colored woman already in the place of honor.

There was still another powerful consideration for making the color line absolute. The “pure” white offspring that was decreed for rulership could be maintained only through the white woman, and if the white man did not marry or cohabit with her, except to a limited degree, how could white supremacy be maintained?

Thus the white slaveholders and the petits-blancs, or little whites, found themselves caught in a trap of their own setting. They had to choose between the white woman and the colored one. But few hesitated over this choice. Lespinasse writes, “The white man transported to St. Domingue in a burning climate the influence of which upon the temperament cannot be denied, could not resist the charms of the young African woman. She had in addition to her allure, a sympathy that Raynal, Moreau de St Mery, Ganau and Coulon have perfectly described. ‘The natural attractions of the Negro woman,’ said Coulon, ‘outshone nearly always the vain adornments and coquetry of the white creoles.’ The white European woman was the first to be disdained and then the white creole woman, who no matter how seductive, had no longer any empire over the heart of the white man.”10

Vaissiere said similarly, “Numbers of masters instead of concealing their turpitude glory in it, having in their houses their black concubines and the children they have had by them, and showing them off with as much assurance as if they were the offspring of marriage. Neither the color, nor the odor, nor any other natural disgust, nor the idea of having a slave as offspring and to see him ill-treated or worked at the vilest of labor, or sold, keep them from these monstrous unions… .

“One can thus see scions of the great names of France—a relative of Vaudreuil, a Chateauneuf, a Boucicaut, last descendant of an illustrious marshal of France pass their lives between a bowl of raw rum and a Negro concubine. Neither age nor absence of good looks is often an obstacle to these half-savage unions. Often these women are the most repulsively dirty and ugly that the Negro race can produce.”11

The law against intermarriage didn’t work either. First, the Church was against it, and some priests, in defiance of the order went on marrying white and black. Second, the Jesuits were then a power in Haiti. They had great farms and an increase in the number of their mulatto slaves meant more wealth. When the slave-trading was abolished, the Jesuits went in for slave-breeding precisely as did the white Virginians.

Impoverished French noblemen would come to Haiti, marry a rich mulatto girl, take her to France, and with her money re-establish his ancestral line. Pons wrote, “French noblemen went to the colonies for the express purpose of repairing, by a matrimonial connection, a fortune wrecked by losses or misconduct. In these cases they despised prejudice. They cared nothing about color, provided it was not absolutely black. Riches were the great desiderata and made up for everything else. They returned to France with their tawny escorts, where their Creole birth detracted nothing from their consequence in polite society.”12 Some of the white men who married the mulatto girls did not even take the trouble to return to France. They stayed in Haiti. Vaissiere wrote, “… this Saint-Martin of Arada, one of the leading citizens of Artibonite, possessing more than two hundred Negroes, which his marriage with a Negro woman, who owned about thirty slaves, alone permitted him to reach the position he now occupied; or like Gascard-Dumesny, who married a Negro woman of seventy years, widow of Baptiste Amat, who had left her a million francs, has become from a mere interne a leading colonist.”

Hilliard d’Auberteuil, writing in 1777, says, “There is in the colony three hundred white men married to mulatto women, some of whom are noblemen.”13 He adds: “There are so many colored people who are so fair that it is impossible to tell them from white, so many families whose origin is forgotten, and whose daughters are married to honest citizens… . The fair mulattoes, who have become rich, have an infallible way, so to speak of elevating themselves to the rank of the whites; even though there are eye witnesses to the dark color of their mother or grandmother. They claim they are descended from the Indians who came from St. Christopher in 1640 when the English drove the French from that island.”14

As for concubinage that was most common. A census taken in 1774 showed that of 7000 free women of color in the colony, 5000 were living as mistresses of white men.15 Very few of these women were public prostitutes. Later, however, according to Vaissière, the number of the latter did increase in the towns.

Not all of the white men were after money, however. Members, even of the high aristocracy lost their heads over the colored women, some of whom must have been of great physical charm if we are to judge by the manner in which certain writers of the time went into raptures over them. As Lafcadio Hearn says, “So omnipotent was the charm of half-breed beauty that masters were becoming the slave of their slaves. It was not only the creole Negress who had appeared to play a part in this strange drama which was the triumph of nature over interest and judgment; her daughters far more beautiful had grown up too, to form a special class. These women, whose tints of skin rivalled the colors of ripe fruit, and whose gracefulness—peculiar, exotic, and irresistible—made them formidable rivals to the daughters of the dominant race.”

So powerful was the charm of these mulatto girls, he says, that it was decreed, “that whosoever should free a woman of color would have to pay to the government three times her value as a slave”

Some of these colored women did not measure up to the European standard in facial profile, it is true, but their superb physiques, the rhythm, the primitive grace of their movements, and especially of their dancing, made them none the less irresistible to some of the most artistic of the whites.

Souquet-Basiege, Rufiz, Cornillac, and other writers thought that these mixed-blood French women—especially those in whom the blood of Europe, Africa, and America were blended—were the most beautiful specimens of the human race. Cornillac, a surgeon, was deeply impressed by those mixed-bloods, who still showed the aboriginal Carib strain. He says, “When among the populations of the Antilles we first notice these remarkable metis, whose olive skins, elegant and slender figures, fine straight profiles and regular features remind us of the inhabitants of Madras or Pondicherry (India), we ask ourselves in wonder while looking at their long eyes, full of a strange and gentle melancholy (especially among the women) and at the black, rich, silky, gleaming hair, curling in abundance over the temples and falling in profusion over the neck—to what human race can belong this singular variety in which there is a dominant characteristic that seems indelible and always shows more and more strongly in proportion as the type is further removed from the African element. It is the Carib blood—blended with blood of Europeans and of blacks, which in spite of all subsequent crossings, and in spite of the fact that it has not been renewed for more than two hundred years, still conserves as markedly as at the time of its first interblending the race-characteristics that invariably reveals its presence in the blood of every being through whose veins it flows.”16

Lafcadio Hearn, who was himself a connoiseur of black beauty, and a later arrival, raved about the black girls. He said, “There is something superb in the port of a tall young mountain griffone, or Negress, who is comely; it is a black poem of artless dignity, primitive grace, savage exultatation of movement.” In her walk “a serpentine elegance, a sinuous charm … With us only a finely-trained dancer could attempt such a walk; with the Martinique woman of color, it is as natural as the tint of her skin.”

He says of one black woman, a bread carrier, “a finer type of the race it would be difficult for a sculptor to imagine. Six feet tall—strength and grace united throughout the whole figure from neck to heel; with that clear black skin which is beautiful to any but ignorant or prejudiced eyes; and the smooth, pleasing, solemn features of a sphinx—she looked to me as she towered there in the gold light, a symbolic statue of Africa.”17

Of the Haitian mulatto girls, he said, “If tall, young, graceful, with a rich gold tone of skin, the effect of her costume is as dazzling as that of a Byzantine Virgin. I saw one young da, who, thus garbed, scarcely seemed of the earth and earthly—there was an Oriental something in her appearance difficult to describe—something that made you think of the Queen of Sheba going to visit Solomon. She had brought a merchant’s baby, just christened to receive the caresses of the family at the house I was visiting and when it came to my turn to kiss it, I confess I could not notice the child; I only saw the beautiful dark face, coiffed with orange and gold and bending over it in an illumination of antique gold… What a da. She represents really the type of that belle affranclne of other days against whose fascination special sumptuary laws were made; romantically she imaged for me the supernatural god-mothers and Cinderellas of the Creole fairy-tales… . Really the impression of that dazzling da. I can even now feel the picturesque justice of the fabululist’s description of Cinderella’s costume: Ca te ka bailie ou mal zié! (It would have given you a pain in your eyes to look at her.”18

ONE OF HAITI’S MOST ILLUSTRIOUS SONS

XXXIII. Alexander Dumas, famous Napoleonic general, and founder of the great Dumas family, In hunting costume. Right: portrait of General Dumas In the Colonial Museum of Paris.

Coleridge thought that the Latin American mulatto women were more beautiful than those of Anglo-Saxon origin. Writing on Martinique, he said, “Our mulatto females have more the look (color) of very dirty white women than that of the rich oriental olive which distinguishes the haughty offspring of the half-blood of French and Spaniards. I think for gait, gestures, shape and air, the finest women in the world may be seen on a Sunday in Port-of-Spain. The rich and gay costumes of these nations sets off the dark countenances of their mulattoes infinitely better than the plain dress of the English.”19 The English were less artistic by temperament, and consequently more commercial and drab—a nation of shopkeepers as Napoleon called them—and the blacks in their colonies reflected this.

Vaissière, who did extensive research on the letters and documents of the period, reveals the great fascination that the black and mulatto women held over the white men in Haiti. He wrote, “We see in this country, writes M. de Arquijian in 1713, only Negro women and mulatto women who have bargained off their virginity for their freedom; and the supervisor, Montholon, declares in 1724 that if the French in Hayti are not careful they will rapidly become like their Spanish neighbors in Santo Domingo, who are three-fourths mixed. In fact in 1734, M. de la Rochalar observes at Jacmel nearly all the inhabitants are mulattoes or are descendants of them. This proves that the penalties placed from the earliest days of the colonies against masters having children by their Negro women was not very vigorously applied… . One governor even made pleasantries upon the manners of a certain Dupas of St. Louis ‘who amused himself by having male and female children by a Negro woman for whom il a des bontés.’ The example of race-mixing sometimes comes from on high and M. de Gallifet, the King’s representative at Cap Haytien was menaced for having kidnapped a Negro woman, who was the most beautiful of the four or five he kept about his bed. The love for the black woman inspired only illicit passions. Greed aiding … it was sometimes consecrated by marriage. In four months, writes M. de Cussy in 1688 there have been twenty marriages with mulattoes and Negro women. The desire to get the wealth of the black woman, as one governor acknowledged much later, will indeed determine unconsciously all the penniless white men, sojourning here, to marry these Negro women, marriages that are not made difficult by the church because of religious principles, and often by self-interest of the priests.”

HAITIAN NOBILITY.

XXXIV. Left: The Duke of Tiburon, Minister of War of Faustin I. Right: Princess Olive, daughter of Faustin I.

Because of the manner in which they had been neglected, some of the white women were very cruel to the colored ones but others reconciled themselves to the situation, while still others entertained a genuine affection for the black and mulatto women who had grown up with them, and who they loved so much that they did not mind sharing their husband’s affection with them. Some even became god-mothers of the mixed blood children. Vaissière said, “Nearly every white young creole girl had a young mulatto or quadroon girl, or even a young Negro one whom she made her cocote. The cocote was the confidante of all the thoughts of her mistress (and the confidence was sometimes reciprocal especially in the affairs of love). She never left the cocote; they slept in the same room; she ate and drank with her, not at table and at feasts, but in eating the creole ragouts in places far from the sight of men.”20

These cocotes often became the concubines of the husbands of the white girls, and served as spies for bringing to the whites what was happening among the Negroes.

As for the unmixed black women, they had little sexual liking for the white men, according to several writers. Moreau de St. Mèry said that it tickled their vanity to be “white men’s mistresses” but that they had an “invincible penchant for the Negro man.”

As regards the white woman and the black man, one finds little mention of their cohabiting. Peytraud cites the case of Marie-Claire Boulogne, who was accused of having killed her new-born child. It was later discovered that the child had been born dead, but since she had confessed that its father was a Negro, she was banished on suspicion of murder. Labat also gives an instance of a white slave-holder’s daughter having a child by a slave.21

But although there is little mention of the black man and the white woman, Napoleon must have had disturbing information on this matter because in his secret written orders to his brother-in-law whom he sent out against Toussaint L‘Ouverture he said that all white women who cohabited with blacks should be returned to France forthwith. As irony has it, his own sister, Pauline, Leclerc’s wife, is commonly said to have broken the order, among her black lovers being named Toussaint L’Ouverture and Christophe, later emperor of Haiti.22

The charges against Pauline are very likely true: One fact is indisputable: Toussaint L’Ouverture had many loves among the white women of the upper class, according to General Pamphile de LaCroix. La Croix relates how when he opened one of Toussaint’s trunks, after Toussaint’s capture, he found a secret compartment crammed with love letters and other tokens of love from society women to whom formerly Toussaint had been but a black slave. “Judge,” he said, “our astonishment when in forcing the double bottom of the safe that contained the secret documents of Toussaint L’Ouverture, to find tresses of hair of all colors, rings, hearts pierced with Cupid’s arrows in gold, small keys, necessaires, souvenirs, and an infinite number of love-letters which left no doubt of the success obtained in love by the old Toussaint. Yet he was black and of repulsive physique.”23

A LADY OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY.

XXXV. Madame Chasseriau, Mother of the famous painter, Theodore Chasseriau.

La Croix, realizing the terrific scandal the letters would have caused, destroyed them all.