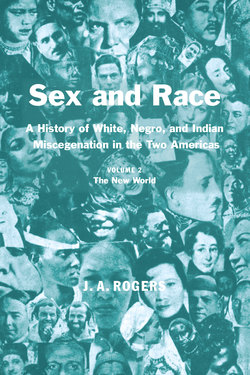

Читать книгу Sex and Race, Volume 2 - J. A. Rogers - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Seven

ОглавлениеCUBA, PUERTO RICO, AND SURINAM

MISCEGENATION in Cuba took place chiefly between whites and blacks because the Indians were soon killed off and Negroes brought in to take their place about 1523. There is little Indian strain in the Cuban.

The royal decree allowing slavery stipulated that no Moors, Jews, or native Africans were to be taken to the Indies but only Negroes who had been reared in Spain under Christian influence. The purpose was to have docile slaves but the blacks were so badly treated that rebellions began soon after and continued for centuries.

So many Negroes were brought to Cuba that they soon outnumbered the whites, a good many of whom were in reality, mulattoes. In 1817, the whites and near-whites were 259,260; the free blacks, dark mulattoes and slaves 379,188. Abbott, who was in Cuba in 1828, estimates that there were 300,000 whites, 200,000 free Negroes and mulattoes, and 500,000 slaves. The 1841 census gave 418,291 whites; 88,054 mulattoes; 64,784 free blacks; 10,974 mulatto slaves; and 425,521 black slaves, thus the black and mulatto population exceeded the white by 171,042. It must be remembered, too, that many of the whites, perhaps the most of them, were really mulattoes, because in Cuba as in other Latin American lands, mulattoes who had money or influence could get their “white” papers. J. M. Phillippo who lived in Cuba in 1856 says that the total number of slaves alone on the island was between 800,000 and 900,000.

Despite the many slave revolts, there was, however, much genuine affection between white and black in Cuba. The island’s first and only good school until 1792 was conducted by a mulatto, named Melendez, according to the Countess de Merlin, a native Cuban, and the majority of his pupils was white. A slave woman, too, was often the foster-mother of the future master or mistress of the plantation. Countess Merlin describes an affecting scene between an invalid white Cuban girl and her Negro nurse. “She took the woolly head of the Negro woman and toyed with it; struck her softly on the cheek, and made a hundred other caresses.”1

With no laws against mixed marriages, whites of both sexes married with the mulattoes and sometimes with the blacks. A white American visitor to Cuba in 1855, wrote, “Many Spaniards married Negroes and their attachment to the blacks is so strong that almost all the mulattoes are their children. White, or Galician, Spanish women had no aversion to marrying Negroes.”2

This has continued to the present. Another white American, Arnold Roller, writing in 1929, said, “The whites, particularly the workers, small shopkeepers and artisans, frequently marry the mulatto girls or live in free unions with them and the children of these unions are always considered white… . Many who in Cuba are considered whites would still be called Negroes in the United States.”3

Though Cuba is listed as a white country the visitor there will find a close ethnic similarity between its towns and the great centres of Negro population in the United States. This is especially true of the populous city of Santiago de Cuba in Oriente province. “Cuba,” says Beals,” considers white blood more potent than do we Americans. Among us, if a man has a drop of black blood he is listed as black, but in Cuba if he has a drop of white blood he is more likely to be put down as white. Hence official Cuban statistics cannot be relied on for any true picture. The 1930 census reports 2,570,000 white and 923,346 colored… .

“Cuba is predominantly a mulatto country. The nambises, the Negro-mulatto ethnic element, constitute the real Cuba. A more correct picture would probably give 30 per cent white; 40 per cent mixed; and 30 per cent Negro… . Oriente is predominantly a black province.”4

Schurz, a more recent writer, says much the same: “The mixture of white and black in Cuba has also proceeded so far since the early introduction of Negro slavery into the island that however light their complexion many of the old families could not pass a test of sangre puro.”5 Of course there has been a considerable immigration of Europeans to the island in more recent times but as Beals says the time has been too short to reverse the actual figures of colored and white.

The mulattoes, who were too dark to pass for white, with the blacks have played a role of great importance in Cuban history. They furnished more than 75 per cent of the fighting men in the wars for independence. Cuba’s most renowned military figure was a dark mulatto, Antonio Maceo. White and black fought separately but there were many of Negro strain in the white regiments. The leader of the whites, and commander-in-chief of the Cuban army, Maximo Gomez, was a native of Santo Domingo and had a light Negro strain, according to Sir Harry Johnston. Gomez was the first president of the republic.

THE PRESIDENT OF CUBA.

XXVI. Colonel Fulgencio Batista, Cuba’s president.

The fight for independence brought all Cubans, regardless of color, closer together, but with American intervention and the introduction of American color prejudice, Cuba had her first great clash between colored and white since the abolition of slavery. In 1912 the colored people, large numbers of them veterans of the war of Independence, revolted under General Estenoz. Thousands were killed. This revolt resulted in an improvement of the racial situation. Today the president of Cuba, Fulgencio Batista, is of mixed white and Negro blood, with a touch of either Indian or Chinese. “He has the flat nose and dextrous white-palmed hands of the Negro,”6 says Carleton Beals. Batista’s complexion is that of a mulatto, while his hair is nearer that of the Indian.

There are also occasional marriages between white Americans and Negro Cubans. In the 1890’s, a white American society belle “of excellent family” chose as her husband, a coal-black Cuban, of great wealth. Dorothy Stanhope in the New York Times, September 16, 1900, describes her as “a reigning belle in a large city of one of our Eastern states, who was always spoken of as the beautiful Miss ——.” Deciding to marry for money, so it is said, she selected “the wealthiest of her suitors, a Cuban, black as night,” who “gave her a palace for a home and all the rest in keeping.” They lived in Cuba.

Cuba has had many distinguished mulattoes. Among them are Placido, her greatest poet; Jose White, celebrated violinist, who won many honors in Europe’s greatest concert halls, and was later head of the Conservatory of Music of Brazil under Dom Pedro II; Juan Gualberto Gomez, who was a dominant figure in Cuban politics for nearly half a century; Paul LaFargue, Socialist writer, who married the daughter of Karl Marx; and Jose Maria Heredia, one of the Forty Immortals of France. Heredia denied his Negro strain saying that he was of conquistador ancestry, but in France, he was generally known as a colored man,7 and his name was linked with a great contemporary of his, Alexander Dumas the Younger, who was of Negro ancestry. Still another Heredia of Cuba, unmistakably a Negro, was a French Cabinet minister in 1887. Both the Heredias married white French women.

Among the most distinguished blacks were Manzano, slave poet, “whose facile and easy prose” exceeds even the flow of his verse; Brindis de Sala, one of the greatest violinists in the history of music, who won the most lavish praise of the critics of France, Italy, and Germany, and who was chief violinist at the Court of William I of Germany, who made him a baron, and approved his marriage to a German lady of rank; General Quintin Bandera and General Guillermo de Moncada, both heroes of the Cuban Revolution. Two more recent distinguished blacks are Morúa Delgado, who was president of the Senate and Minister of Agriculture; and General Manuel de Jesús Delgado who was Minister of Agriculture. Arredondo gives a partial list of noted colored Cubans.

Puerto Rico

What is true of Cuba is also largely true of Puerto Rico. The Spaniards arrived in the island in 1508, and in less than ten years the Indians were either killed off or driven into the mountains. Negroes were brought in such numbers to take their place that as early as 1544, Governor Lando wrote, “The island is so depopulated that Spaniards are scarcely seen; only Negroes.”8

Among the eighteen companions of Ponce de Leon in the settlement of Puerto Rico was at least one Negro, Pedro Mexia,9 who was wealthy, and who married the widow of an Indian chief, Donna Luisa. Mexia was killed while defending her from her own people who objected to her being a Christian. Brau reports several marriages of whites with Indian women

So many Negroes were brought to Puerto Rico in proportion to the white population that in the seventeenth century runaway slaves and their descendants, who had settled near San Juan, the capital, alone were strong enough to repel a British attack on the capital. These blacks, who had organized themselves into a militia, known as Los Morenos, or Moors, drove off the British commander, Sir Ralph Abercrombie, who left behind 250 dead, many prisoners, and a large quantity of supplies.10

Small as the white population of Puerto Rico was it had a considerable degree of Negro strain. As in Venezuela and Mexico, many who were visibly Negro, had themselves declared “white” by the purchase of “white” papers. A white American who visited Puerto Rico in the 1850’s says, “During the years of neglect (by Spain) it had been the custom to allow the free mulattoes to purchase or otherwise obtain “white papers” and all such persons, with their descendants have since been reckoned as whites under the denomination of ‘blancos de tierra.’ More than one hundred thousand of these “whites of the country’ figure in these returns, and Schoelcher, from whom I obtained these facts, tells us in his ‘Colonies Etrangeres,” quoting the Padre Inigo, the historian of Puerto Rico, that the greater part of the population of the island is really composed of mulattoes.”11

According to figures given by Padre Inigo Abad, who wrote about 1780, there were on the island in 1777, 29,263 whites; 33,810 pardos, or mixed bloods; 2,803 free blacks; and 6,487 slaves, or 13,837 more mulattoes and blacks than whites. And as was said, many of the whites were of Negro ancestry.

TWEEDLEDUM AND TWEEDLEDEE.

XXVII. Three Puerto Ricans in New York—Two “colored” and one “white.” Suit was brought to take the “white” child from the adopted mother, on the ground that Negroes ought not to rear white children. Which is “white” and which “colored?”

During the years that followed more blacks continued to arrive in the island and few, if any emigrated, while there has been no great immigration of whites—in short, the population has been due largely to native increase—but now, according to the United States census, it has become more than 75 per cent white.

The percentage of foreign-born on the island is less than 2 per cent, being in 1917, only 1.1 per cent. In 1920, there were only 8,167 foreign-born, and in 1930, only 6017 in a total population of 1,543,913.

The 1920 census gave 948,709 whites, and 351,062 colored; the 1930 gave 1,146,719 whites and 397,156 colored. Thus there can be but one explanation, and that is, that mulattoes continued to be “whitened” not by royal decree, as in the past, but by social sanction in order to maintain the old slave tradition of superiority over the black, or nearly black man. One fact is certain: There could not have been such a great ethnic change in only three or four generations, unless white people had poured into the island, which, as was said, they did not.

In short, if we call the European white, then it will be certainly a stretch of the imagination to call the majority of Puerto Ricans white, also. As for the prediction so often made that the whites of Puerto Rico will before long absorb the blacks, that is wild optimism. Any New Yorker may have a fair idea of a cross-section of the real Puerto Rican population by going to Harlem where there are between 80,000 and 100,000 of them.

The American Guide Series; Puerto Rico, a United States government production, says as regards the “race” of the Puerto Rican population: “According to the 1935 census persons classified as ‘colored.’ that is, Negroes and persons of white mixed and Negro blood, numbered 23.8 percent of the total population. A decrease in the number of persons reported as colored is probably due not so much to interbreeding as to a change in the concept of the census enumerators. The remark has often been made that on the mainland a drop of Negro blood makes a white man a Negro; while in Puerto Rico a drop of white blood makes a Negro a white man.”12

Puerto Rico seems to have absorbed more Indian strain than did Cuba. There were Indians on the island as late as the early nineteenth century. A large proportion of the population is what is known as jibaro, the lighter-skinned members of which, like the poor whites of the South, than whom they are even poorer, boast of their Spanish blood. But the term, jibaro, itself, savors of Negro strain. The early Spaniards called the offspring of a mulatto and an Indian with another Indian, a jibaro. Rosario, in his excellent study of the jibaros, shows that they have much of the Indian and the Negro in their ways, especially in their music. The genuine jibaros are certain Indians of Peru.

The lighter-colored Puerto Rican is very sensitive on the subject of Negro ancestry. It is a skeleton in his closet, to which it is most impolite, if not insulting, to refer Perhaps nothing irritates the average Puerto Rican mulatto more than the thought that in America, he is called a Negro. In the Puerto Rican section of Harlem, there is little or no color prejudice between its members but there are mulatto Puerto Ricans who will rarely go to the white sections of New York because while they are considered white in their own quarter, in the white sections they are looked on as Negroes.

A case of how the American dictum about color may act tragically on Puerto Rican sensitiveness—a case much cited—is that of Albizu Campos, Puerto Rican Nationalist leader, and brilliant Harvard graduate, who wound up with a ten-year prison term in Atlanta penitentiary. Campos, son of a white man and a colored woman, while at Harvard claimed to be an Indian, it is said, and was accepted, or pretended to be accepted, as such at the university, but when his class honors entitled him to represent Harvard abroad, his “Indian” blood availed naught; then he was just a colored man for whom such an honor was too high. This incident is said to have fired Albizu Campos in his determination to win freedom for Puerto Rico. As a result of his activities several persons were killed, one of them, Colonel E. F. Riggs, an American, and island chief of police. Campos, implicated in the disturbances, was found guilty.

In the Selective Service Draft of 1940 to 1942, many Puerto Ricans, very obviously mulatto, were set down as white and drafted into the Army as such. As one draft registrant said, “Putting them down as what they really are would be dynamite.” Much of the same held true for other colored men from the Latin American lands.

Surinam (Dutch Guiana)

In Surinam, the Dutch mixed freely with the blacks, who were imported in such numbers from 1667 onwards that numbers of them living in the interior, the Djukas, or Bush Negroes, not only won their independence, but forced the whites to pay them tribute.

Of all the slave colonies, Surinam seems to have been the most cruel, no doubt because of the resistance of the blacks against slavery. The Dutch women especially were very harsh to the black women of whom they were jealous because of the manner in which their white husbands abandoned them for the black girls. Stedman, who spent five years in the colony, and himself took a mulatto mistress of whom he was dotingly fond, tells of one white woman, who seeing a very beautiful black girl belonging to her husband and “observing her to be a remarkably fine figure with a sweet engaging countenance, her diabolic jealousy instantly prompted her to burn the gir’s cheek, mouth, and forehead with a red-hot iron. She also cut the tendon Achilles of one of her legs thus rendering her a monster of deformity.”13

MIXED BLOODS OF SURINAM.

XXVIII. A mulatto girl and a quadroon of Dutch Guiana In the eighteenth century. (Stedman).

The white men made very free with the black women. Stedman says, “If a Negro and his wife have ever so great an attachment for each other, the woman, if handsome must yield to the loathsome embraces of an adulterous and licentious manager or see her husband cut to pieces for endeavoring to prevent it.”14

The English seized a part of this colony in 1803, and were equally free with the Negro women, thus increasing considerably the number of mulattoes. St. Clair, who lived in the colony says, “The first thing generally done by a European on his arrival in this country is to provide himself with a mistress from among the blacks, mulattoes, or mustees. The price varies from £100 to £150 sterling. Many of the girls read and write and most of them are free… Two of our officers were living in barracks with two of these girls; one, in Demerara, Lieut. Myers, had a beautiful young mulatto, and Lieut. Clark in Berbice had a fine handsome black woman.”15

The slave women in Surinam were compelled to go nude above the waist and the young girls absolutely nude, thereby arousing the sexual appetite of the white men, especially new arrivals. Beautiful, shapely black girls in their teens waited on table in the homes of the rich with not a stitch on, causing no little perturbation to newly-arrived white men. In the morning before the visitor was out of bed “a pretty black Venus wearing only a smile” would bring in his coffee.

St. Clair relates how he visited one of the finest mansions in Demerara, and how his host, his wife, and two pretty white daughters, together with a blooming young widow, were served at dinner by four Negro maids “as naked as they came into the world. I was astonished at such an exhibition before persons of their own sex.”16

Some of the black women arrived in Surinam already with child by white men. Such usually fetched a higher price. Stedman tells of a Dutch ship captain who sold the woman whom he had made pregnant on the voyage for a larger sum than he got for the other women.17 St. Clair, who saw the arrival of a slave ship, tells how lean and starved were the slaves, but how sleek and well-fed were the Negro mistresses of the white men on the ship. He says “On reaching the cabins, which belonged to the cabin and mate, I found five or six young girls, as naked as they were born, who formed the seraglios of these two sultans and were kept fat and in good condition.”18

ADDITIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arredondo, A., El Negro en Cuba. 1939. This writer gives a list of distinguished Cuban Negroes.

Cabrera. R., Cuba and the Cubans. 1896. (Trans, by Laura Guiteras.)

Ortiz, F., Hampa Afro-Cubano. 1916.

Rosario. J. C., The Development of the Puerto Rican Jibaro. 1935.

___________

1 Merlin, Countess de., La Havane, Vol. 2, p. 184. 1844.

2 Philalethes. D., Yankee Travels Through the Island of Cuba. p. 244. 1856.

3 Nation. Jan. 9. 1929, p. 55

4 Beals, C. America South, p. 50. 1937.

5 Schurz, W. L., Latin America, p. 70. 1941.

6 Beals, C, America South, p. 162. 1937.

7 Thompson, V., Cosmopolitan Maga, Vol. 29, p. 19 (1900).

8 Van Middledyk, Puerto Rico, p. 92. 1903.

9 Brau, S., La Colonizacion de Puerto Rico, p. 215. 1907.

10 American Guide Series: Puerto Rico, p. 178. 1940.

11 Remarks on Hayti as a Place of Settlement for Afric-Americans, p. 33. 1860.

12 American Guide Series: Puerto Rico, p. 110. 1940.

13 Stedman, J. G., Narrative of a Five Years’ Expendition to Surinam, Vol. 2, p. 25. 1813.

14 Stedman, Vol. 2, p. 284.

15 St. Clair, T. S., A Residence in the West Indies, etc., Vol. 1, p. 112. 1834.

16 St. Clair, Vol. 2, p. 165.

17 Stedman, Vol. 1. p. 215.

18 St. Clair. Vol. 1. p. 195.