Читать книгу The Man Who Invented Aztec Crystal Skulls - Jane MacLaren Walsh - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

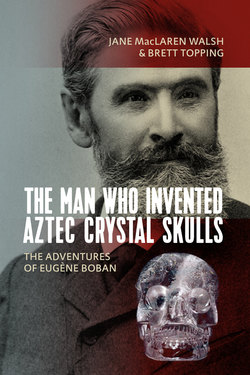

Boban Family History

ОглавлениеEugène André Boban Duvergé was born in Paris on 10 March 1834. The surname Boban, which he and some family members used occasionally with Duvergé or Duverger, does not seem particularly French, and caused some ongoing confusion among even his close friends and colleagues as to its spelling. It may have its origins in Croatia, where Boban is a rather common surname, associated with the village of Bobanova Draga in what is now Bosnia Herzegovina (Bellamy 2003). This said, his paternal ancestors had lived in France since before the 1740s.

The first family members recorded in France were his great-great-grandparents, René Boban, a master cloth maker specializing in serge, and his wife, Marie Houdu, who lived in Sablé-sur-Sarthe, between Le Mans and Angers. For several generations the family continued to live in and around Angers, moving back and forth to Paris as their economic circumstances dictated.

Eugène’s grandfather, André Michel Boban Duvergé, was a tailor, like his father and grandfather before him. He married three times. His first wife was Marie Renée Hémon, a seamstress. She died in 1805, leaving him to raise their infant son, also named André.

Two years later, at the age of twenty-nine, André Michel married Marguerite Victoire Licoys, the 21-year-old daughter of a day laborer, who was also a seamstress. She died in 1810, leaving him with a two-year-old son named René Victor Boban dit [called] Duvergé, born in Angers on 4 May 1808. He was Eugène Boban’s father.

In 1815 André Michel, now thirty-seven and a widower for a second time, married Henriette Chardon. Her parents were listed as property owners in the marriage document, so, presumably, she came from a prosperous family. Within the next ten years André Michel and Henriette had three daughters: Françoise Henriette, called Fanny, born in 1816 in Angers; Henriette, born in 1823 in Paris; and Victorine, born in 1825, also in Paris. Eugène Boban’s aunts Fanny and Henriette would play a significant role throughout his life.

As the birth location of two of his daughters’ attests, André Michel and his third wife went to Paris in the early 1820s in search of business opportunities. The family lived at 35, rue des Boucheries in Saint Germain, quite close to the church of Saint-Germain-des-Prés on the left bank. The abbey and cloisters of this church had been one of the wealthiest in France, but during the French Revolution they were nearly destroyed by an explosion and fire. In the nineteenth century the area around the surviving church became somewhat less fashionable than it had been in the eighteenth century.1

For reasons of his own, Eugène’s father, René Victor, used only the surname Boban, unlike other immediate family members, and was the first to pursue a profession outside the textile trades. He followed his father to Paris and became a gainier—a craftsman who produced chests, boxes, jewel boxes, scabbards, and other leather-covered luxury items. Gainiers often dyed the hides they used and occasionally gilded and embossed them with specialized tools. Their products were intended for the wealthier classes. In March 1830, when he was twenty-one, René Victor married Laurence Michelle Simon, a laundress who was nineteen. The couple lived in Paris at 3, rue Cardinale, a block away from André Michel’s house, near the church of Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

René Victor and Laurence Michelle Boban eventually had five children. The eldest, Rose Louise, was born in 1831; Eugène André in 1834; and Marie Françoise in 1836. These three were born at rue Cardinale. Julie Félicité, the fourth child, was born around the corner at 1, rue Childebert, in 1838. The youngest, Charlotte Heloise, was born in 1841 in Montrouge, a working-class suburb of Paris, later the 14th arrondissement.

René Victor and his family seem to have fallen squarely into the stratum of French society known as the petit bourgeoisie, a broad denomination that, as historian Gordon Wright notes, “included the mass of little independents of city, town, and village—small enterprisers, shopkeepers, artisans, clerks, schoolmasters, petit employees of the state.” As though speaking about this family directly, he adds, “Some of them inherited an old family tradition of shop keeping or craftsmanship” (Wright 1987: 166).

The Bobans lived in rented flats mostly in the Saint-Germain-des-Prés district, until the early 1880s. That their standard of living was relatively modest is indicated by the address of one of the buildings in which they resided, 22, rue des Grands Augustins, constructed in the 1670s.2 The apartment shared by the seven members of the family consisted of two small rooms with a fireplace and a small kitchen alcove. Several other artisans were living and perhaps working at the same address. The other tenants may have been involved in the gainier trade as well, since they are listed as upholsterers, staplers, and leather guilders.3 It seems as though the family was struggling to get by, as were many Parisian artisans and tradespeople of the day.

The history of the Boban Duvergé family in Angers and Paris is illustrative of the economic and social developments of the nineteenth century in France. Following the debacle of the Napoleonic Era, the country was slow to industrialize, falling well behind European rivals such as Germany and England. However, textile production was one area that did experience industrial growth of sorts, although the majority of textile manufacturers were small businesses. According to the economist Armand Audiganne, in 1847 only 318 workshops in the department of the Seine, which included Paris, used mechanical power or employed more than twenty workers. Of the 29,216 clothing and shoe producers in Paris in 1847–48, 18,930 (65 percent) consisted of a proprietor and a single worker or a proprietor working alone (Price 1972: 6–7).

Aside from the slow pace of industrialization in France, another indication of stagnation in economic and social development was the lack of upward mobility in most of the country. At mid-century, the one exception was Paris, although the majority of individuals who were able to enhance their prospects in the capital had moved there from less advantageous circumstances in the provinces, like the Boban Duvergés.

For the first decade and a half after Eugène Boban’s birth, the Orleanist king Louis Philippe ruled France. Uninterested in the pomp and formality that had been hallmarks of previous generations of nobles, he was sometimes called the “Citizen King” or more derogatorily the “Grocer King” (Horne 2006: 251). After 1840, he and his ministers, particularly former historian François Guizot, who became foreign minister and later prime minister, helped expand French business through protective tariffs and low taxes, government deregulation and large expenditures in public works. Like many conservatives today, Guizot firmly believed that France was a country of equal opportunity and that those who failed to get rich and acquire the privileges of the rich had only their own limitations to blame (Wright 1987: 118, 154).

Boban would have finished his primary schooling at about the age of twelve in 1846. There is no record that he went on to receive a secondary education, so he probably assisted his father as a gainier at that stage, learning the trade as an apprentice.

From 1845 onward France had experienced extremely poor harvests, partly caused by a potato blight that had begun spreading across Europe. The situation was extremely difficult for the poorer classes, who saw prices of their two staple foods—wheat and potatoes—rise dramatically at the same time, with other food products in short supply. The weakness in the farming sector soon rippled throughout the French economy. In 1847 alone 4,672 businesses failed in France, compared with 2,618 in 1840, which had not been a good year either (Price 1972: 84).

Support for Louis Philippe’s government had eroded among many classes in France by the beginning of 1848, a year that was to experience revolution and chaos across Europe (Wright 1987: 125–26). Parisian students and workers took to the streets, clashing with the police on 22 February 1848. Called upon to restore order, the National Guard proved disloyal to Louis Philippe, and the clashes turned into all-out rioting. The following day the king attempted to calm matters by firing Guizot, who had become hugely unpopular.

The news of Guizot’s dismissal inspired a public demonstration of thanks in front of the minister’s former office. Unfortunately, what started as a celebration ended in tragedy.

A column of students and artisans, unarmed, but singing ‘Mourir pour la patrie,’ came down the boulevards; at the same instant a gun was heard, and the 14th Regiment of the Line leveled their muskets and fired. The scene that followed was awful. Thousands of men, women, children, shrieking, bawling, raving, were seen flying in all directions, while sixty-two men, women, and lads, belonging to every class of society, lay weltering in their blood upon the pavement. (St. John 1848: 167–68)

After this the situation in Paris was beyond Louis Philippe’s control, and he abdicated in favor of his grandson. (Wright 1987: 126–27).

The citizens of Paris then declared a Second Republic (the first having been established during the French Revolution) and appointed a temporary government. At first it seemed that a new era of universal accord and understanding had dawned (Price 1972: 95–96). Despite this apparent harmony, the economy worsened bringing about even greater unemployment.

On 15 May the National Assembly came under attack as thousands of armed workers convened on its chambers demanding reform. On 21 June the situation got out of control when the Assembly issued a decree restricting membership in the National Workshops, which had provided some financial support for unemployed workers. The announcement was like a spark to tinder. Barricades immediately appeared all over Paris, and for the next five days skirmishes and pitched battles occurred across the city between working-class Parisians and the government’s soldiers. By the time the fighting ended, 900 soldiers along with 1,500 citizens, and perhaps as many as 3,000, lay dead (Knapton 1971: 392; Wright 1987: 134).

The fiercest battles took place around the enormous barricades near Place de la Bastille and Faubourg Saint-Antoine, immortalized by Victor Hugo in Les Misérables—across the Seine and some distance from the Boban family household. There also was intense fighting just across the river from them in the 3rd and 4th arrondissements, and the Left Bank and Latin Quarter up the street (Price 1972: 170). Living day-to-day in Paris during the June Days of 1848 had to have been frightening and disturbing for the family as for so many others. Eugène was only fourteen at the time, and the violence and killings must have affected him deeply. As order was restored in the weeks and months that followed, some 12,000 to 15,000 people were arrested, with about a third being deported to the French colony of Algeria (Wright 1987: 134; Knapton 1971: 392).

The bloody conflict of June 1848 was to have long-term repercussions for France’s prospects for peaceful reform and social progress. As British historian Roger Price notes:

The June days clearly revealed how far men’s attitudes had changed since the first relatively harmonious days of the Republic. They indicated the insufficiency of political reform, even that of granting universal male suffrage, as a means of giving satisfaction to the poor. They indicated the desperation with which those who had a vested interest under the status quo would defend this. Above all they indicated the shape of things to come by revealing this basic split in society and convincing many that differences between social groups could only be resolved by conflict. French society and its politics were for long to bear the mark of the hatreds generated by the insurrection of June 1848, and its brutal suppression. (Price 1972: 155)

The economic impact of the revolution of 1848, which grew out of the disenchantment and frustration of the working class unable to make a living wage, was devastating. The business class refused to invest capital in their operations, and “no real signs of recovery would be seen until 1851” (Traugott 1988: 22). Unemployment would continue to rise for the next few years, and workers would continue to be exploited by subcontractors and the growth of piecework, which was particularly prevalent in the textile industry.

With France in an economic tailspin at the end of 1848, the news that gold had been discovered in California at the beginning of the year came as a thunderclap of good news. The French had already begun developing a keen interest in the American West, due partly to the reports from John C. Frémont’s exploratory expeditions of the West and California throughout the 1840s, which had become available in translation. France considered Frémont a native son because of his French-Canadian ancestry, taking to heart his expansionist view that the American West was a land full of opportunity and adventure. Once gold was discovered, the bookstalls of Paris displayed more and more information about California—sailors’ reminiscences, accounts from Frenchmen living in California, articles taken from American publications—all of which added heat to the gold fever (Brands 2002: 94).

Figure 1.1 Duvergé sisters’ invoice (courtesy of Sylvain Bertoldi, Archives municipales d’Angers, 1 Num. 15).

According to an 1851 census, Boban’s grandfather, who had dropped the Boban surname and was known as André Michel Duvergé, had left Paris to return to Angers with his wife and two of their daughters, Fanny and Henriette. The youngest daughter, Victorine, may have stayed in Paris or perhaps had died, since she is no longer listed in census records in either Angers or Paris. André Michel, then seventy-two, is described as supported by the labor of “his children”4—his daughters, by then thirty-five and twenty-eight, who were corset makers or corsetières. René Victor’s younger half-sisters had followed the Boban Duvergé tradition to become successful in the textile industry, ultimately owning an award-winning business in Angers that manufactured corsets, “gilets de santé,” which may have been special vests or a type of undergarment, and men’s shirts.

Boban’s grandfather, André Michel, died in October 1851, but his third wife, Henriette Chardon, and his daughters continued to reside in Angers at least until the early 1860s. Their business seems to have prospered. Fanny married a blacksmith just a few months before her father’s death, and they had a domestic as a member of their household. Their names last appear in the Angers census in 1861.5

In 1852, Louis Napoleon, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, declared himself Emperor Napoleon III in a bloodless coup d’état that ended the Second Republic. One of his first enterprises was to design the modernization of Paris in collaboration with Georges-Eugène Haussmann, a civil servant and city planner who was prefect of the Seine region. Napoleon III and Haussmann envisioned the complete transformation of the capital into a safer city with better housing, sanitation, and more open communities. Additionally, they designed tree-lined boulevards too wide for the barricades that had figured so prominently in 1848, which would also provide easy access for the police and the military. There was a growing feeling in the country that the capital’s insurgents needed to be controlled. Eight times since 1827 Parisians had brought life and commerce to a standstill by erecting their infamous barricades, and this needed to be stopped (Merriman 2014: xiv).

In August 1853, the Bobans’ eldest daughter, Rose Louise, was married. The family was still living in two rooms at 22, rue des Grands Augustins in the 6th arrondissement, only a few blocks from their original home at rue Cardinale. Rose Louise’s husband, André Martial Backès, was a gainier like her father, and may have worked with him.6

Eugène André Boban was nineteen when his older sister was married in the St. Sulpice church. If he had completed his schooling around the age of twelve, he would have already been working with his father for about seven years. Prior to the education reforms of the late 1880s in France, school ended for most boys after they had made their first communion (Prost 1968: 100–2). In 1852 the baccalauréat ès lettres and the baccalauréat ès sciences were created. One had to be sixteen years old to have the right to take this examination, which, if one passed, gave access to university or advanced studies. Boban’s name does not appear in the records of the baccalauréat tests for those years, however (Pascal Riviale, pers. comm.).