Читать книгу Antoni Gaudí - Jeremy Roe - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

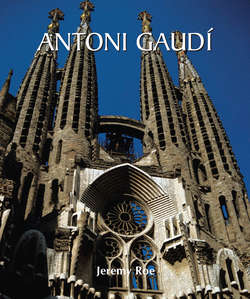

Gaudí’s Barcelona

ОглавлениеGaudí and the Architecture of his Day

20. Casa Vicens, Tower detail.

Gaudí’s support for Catalan nationalism combined with his dedication to the Catholic faith, were important social and cultural factors that informed his work as an architect. These aspects of Gaudí’s work can be examined in more detail, through an analysis of the development of a modern discourse and practice of architecture in Barcelona. Integral to these developments was Barcelona’s national and spiritual identity. Both had evolved over the course of long histories spanning centuries, however in the nineteenth-century they were given renewed vigour and, what is more, became closely linked.

At the heart of this cultural change was the growing industrial strength and economic wealth of Barcelona and Catalonia as a whole. Architecture provided a key medium for individuals and the city to define a modern identity and express the new found optimism the modern era promised. This chapter locates Gaudí and his work amidst his contemporaries, and seeks to view him less as an isolated genius, instead as a man of his times whose work sought to embody many of the ideals of Barcelona as an historical, spiritual and modern city.

The following discussion combines discussion of historical and theoretical themes with an analysis of a series of works by Gaudí. Some of these are designs on paper and were never built or are now lost, while others are completed buildings. The intention is to provide a general introduction to Gaudí and Barcelona as the nineteenth-century merged into the twentieth, however it is also centred around the statement of Juan Bassegoda Nonell that,

“When discussing Gaudí one cannot distinguish the concepts of architect, interior decorator, designer, painter or artisan. He was all of these things at the same time.”

The works examined illustrate the diversity of Gaudí’s skills, and although many of them could be called minor works they all offer fascinating insights into his design, art and architecture.

Gaudí may be identified with a number of artistic and intellectual currents running through Western Europe as industrialisation brought rapid change to almost all aspects of life. The Arts and Crafts Movement and the style known as Art Nouveau are the clearest parallels.

However, to map these webs of connections frequently offers a vision of the past configured more by contemporary interests. The approach taken here is to focus on the specific cultural setting of Barcelona, and in particular the movement known as Modernisme, which should be translated as Modernism with caution if at all, as it refers to a very specific period from around 1890 to 1910.

21. Park Güell, Fountain.

Modernisme

Modernisme is applied to a range of visual and literary arts. With regard to architecture the term describes a group of architects led by Gaudí and Domènech i Montaner but also including other names such as Josep Marià Jujol, who worked closely with Gaudí. Where modern cultural movements begin and end is always a point of debate. Some historians would place the start of Modernisme between 1883 and 1888 with Gaudí’s Casa Vicens while others not until Domènech’s work for Barcelona’s Universal Exhibition in 1888.

Consensus seems to have been reached that Modernisme as an architectural movement had run its course by 1910, which raises the issue of where to place Gaudí’s last works such as the Sagrada Familia. Robert Hughes states:

“In certain respects Gaudí was not a modernista architect at all. His religious obsessions, for instance, separate him from the generally secular character of Modernisme. Gaudí did not believe in Modernity. He wanted to find radically new ways of being radically old…”

However, Gaudí may undoubtedly be identified as making a key contribution to Barcelona’s Modernisme. To explore his identity as a ‘modern figure’ the concerns of Modernisme need to be considered in more detail. Attention will be focused firstly on the needs of the city, then on theories of architectural style and finally on the ideological dimensions of architecture.

22. Casa Vicens, Lateral façade.

23. Park Güell, Leaning columns of the viaducts.

Barcelona: The Growth of a Modern City

The history of nineteenth-century architecture in Barcelona is marked by a need to respond to the growth of the city. The rapid growth of population produced by industrial factories led to urban expansion beyond Barcelona’s famed medieval quarter with its winding Gothic streets.

In 1859 the City Council held a competition for designs for a new urban plan. It was won by the engineer Ildefons Cerdà, who presented an abstract rational design of straight streets divided into equal blocks of living space, named the Eixample. At its heart were two diagonal avenues which intersected with a third horizontal one to create what is known today as the Plaça de las Glòries Catalanes.

In 1860 the first stone was laid by Queen Isabella II and Barcelona’s appearance as a modern city was decided. Subsequent generations were critical of the design, for the lack of variety that it imposed on the city.

To maintain a focus on Gaudí it is not possible to consider in detail the merits or defects of Cerdà’s plan; in any case it has subsequently been distorted by developers. Cerdà’s plan had intended to integrate into the city important architectural features and social amenities to make urban life bearable, such as patio gardens at the heart of each block of apartments, centres for medical care and food markets. Cerdà’s design was based in part on research of the existing living space of the city, and responded to the poverty that he saw.

While subsequent generations sought more imaginative solutions to the problem of urban space the design brief they were faced with was similar: to solve the social problems raised by changes to urban life.

Furthermore, Cerdà’s Eixample established a standard type of townhouse with a façade facing the street, another looking onto a courtyard at the rear, and with load bearing walls built around patios that provided ventilation. The Casa Batlló and Casa Milà are Gaudí’s contribution to Cerdà’s plan and each are based on the type of house established by the Eixample.

Projects such as the Park Güell were also inspired by the aim to improve urban life, but in a less abstract way.

Finally, the scope of Cerdà’s plan is a representative example of the new spirit that animated the minds of Barcelona’s architects and patrons. While Gaudí and his contemporaries, the generation of Modernisme, thought very differently to Cerdà they all shared the confidence and vision to plan on a bold and grand scale.

24. Casa Milà, Façade from Calla Provença, balcony detail.

25. Casa Milà, Window detail view from the courtyard.

Theories of Architecture and the Search for a Modern Style

Cerdà’s plans for the city were underpinned by his belief that, “… we lead a new way of life, functioning in a new way. Old cities are no more than an obstacle.”

Considered in the context of nineteenth-century architecture his statement signals the distinction between an engineer and an architect.

For the architectural community the buildings of old cities, towns, and even ruins were an important source of inspiration for architectural style, which is a second factor informing Modernisme. Two currents of thought animated responses to the history of architecture: firstly, international developments in architectural theory and practice, and secondly, the development of a modern Catalan architecture.

Both of these formed an important foundation for Gaudí’s development as an architect. The generation of his university teachers had been important in initiating this process. Elias Rogent i Amar was an architect whose work comprised both these elements. Unlike Gaudí, Rogent had travelled widely in Europe.

In addition to this he had studied the works of the French theorist Viollet-le-Duc, who is known for his important analysis of Gothic architecture, which concentrated not on its aesthetic appeal, but instead on the structural elements at its core.

The academic study of style in this French theorist’s work provided a foundation for an increasingly eclectic use of architectural styles and decorative motifs. In Barcelona this eclecticism was frequently based on the use of regional Catalan styles, and often supplemented with other national Spanish styles such as the Moorish style.

An example of this gradual eclecticism in Rogent’s work is found in the first major building added to Cerdà’s Eixample.

In 1872, after twelve years of work, the new University of Barcelona was opened. On approaching the building there is little about the Romanesque style that declares itself as modern. However, no building from the Romanesque period exists on such a scale. The sober and ordered style places an emphasis on the horizontal plane created through the repetition of the arches on each storey. The rhythm created by the arches creates a harmonious effect and animates the imposing bare wall. The building evokes the form of a monastery: during the medieval period the monastic orders had made fundamental contributions to the establishment and the development of European universities. The choice of style is also concerned with origins. Catalonia is especially rich in Romanesque architecture and Rogent’s choice was guided by an interest in employing a national style.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Купить книгу