Читать книгу Antoni Gaudí - Jeremy Roe - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Perspectives on the Life of Antoni Gaudí

Religion and Spirituality

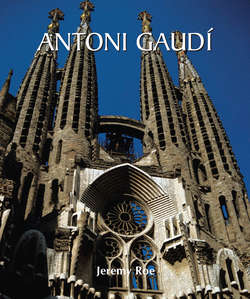

ОглавлениеWorking on the Sagrada Familia, which would become his crowning achievement in the field of ecclesiastical architecture, despite remaining unfinished, Gaudí came into contact with another association, the Associación Espiritual de Devotos de San José. The formation of these voluntary organisations with a pedagogical or social remit was a Europe-wide phenomenon. The association was led by José María Bocabella Verdaguer, whose meditations at the mountain church of Montserrat guided him to found the association. Publishing religious propaganda was a central activity of the association in its drive to defend traditional Catholic values against atheism, socialist and anarchist political ideas, and the immorality that accompanied the rapid growth of Barcelona as well as other European cities.

Gaudí’s connection to Bocabella will be discussed in more detail later, but it would be wrong to identify Gaudí solely with this religious group, which was only one part of a greater movement to revive the faith and status of the Catholic Church in the modern world.

Furthermore, Gaudí’s religious beliefs are more complex. They may be traced back to his traditional upbringing and, Van Hensenbergen has also argued, that his religious belief, as well as that of many of his intellectual peers, was coloured by a perceived connection between spirituality and aesthetic pleasure and sensation. The Catholic Church has always recognised the role of the visual and literary arts, and shown its dexterity to incorporate, as well as guide, changes in style and expression. Following Van Hensenbergen’s thesis it may be argued that Gaudí’s work marks a significant chapter in developing a modern aesthetic for the Catholic Church. Yet it is important to note that his vision was as much if not more of the Gothic world as the modern.

Gaudí’s religiosity signals his distance from concepts of modernity. The historian Cirlot records the following definition of art by Gaudí:

“Art is something so elevated that it has to be accompanied by pain or misery to provide a counterweight in man; if not, it would deny any equilibrium.”

The status Gaudí gives to art identifies his thinking as modernist yet that it should be balanced by pain or misery suggests that his philosophy of art is framed by Catholic doctrine and its emphasis on original sin. The dialectic he evokes does imply an existential dimension to his work, yet Gaudí always sought to elevate the beholder beyond the trappings of existence to the spiritual world. Such concerns underpin his reworking of the Gothic style, which was radical in many ways, but was also shaped by a concern to sustain the traditions – both architectural and metaphysical – of the medieval period. Another example of the religious dimensions of Gaudí’s thinking is his opinion, frequently cited, that “beauty is the radiance of truth.” A theological truth is implied here. Without doubt this view of the past was ‘rose-tinted’.

Gaudí was not alone in this vision of an ideal medieval society. In Britain Ruskin and William Morris looked to the medieval era for ideals of both artistic work and social organisation which would result in a moral and harmonious society.

17. Ricardo Opisso, 1901. Gaudí working in workshop of Sagrada Familia.

18. Temple of Sagrada Familia, Details of architectural decoration forms.

Gaudí’s buildings for Güell illustrate the religious and utopian vision that the architect and his patron shared. The medieval world view evoked by Gaudí’s work is also encountered in the allusions to palaces and castles of his domestic architecture for his wealthy patrons, the factory and the warehouse having become the modern fiefdoms. Although today discussion of such utopian ideals might appear naïve to modern visitors, their evocation in stone, space and light remains powerful. Another aspect of Gaudí’s traditional outlook is noted in the way he organised his workshop with its many craftsmen. In addition to the emphasis placed on the use of manual skills, Gaudí maintained long working relationships with a range of architects such as Berenguer or Jujol, who both went on to become important independent architects in their own right.

As well as his equals in terms of education, Gaudí commanded respect from all of his team of assistants and he is recorded as being a strict but fair overseer. His paternalistic attitudes are noted for example in his encouragement of the workers not to drink alcohol and the allotting of lighter duties for the elder workers. A detailed study of the religious circles Gaudí frequented during his life remains to be undertaken. An additional association he was connected with was the Cercle Artístic de Sant Lluc. St Luke is the traditional patron saint of painters and this group, founded in 1894 by the sculptor Josep Lilmona, sought to promote Catholic art, as well as to counter the immoral avant-garde activities of Barcelona’s modernista artists, such as Picasso. Gaudí became a member in 1899.

It is apparent that art was a fiercely contested space in Barcelona between those wanting to preserve tradition and their adversaries wanting to overthrow it. A number of caricatures explicitly parody Gaudí’s religious beliefs, including a drawing by Picasso. In any case, a cautious approach is required to focus more closely on the relationships between Gaudí and Barcelona’s Catholic intellectual fraternity.

Gaudí’s famed individualism and his artistic vision mediated his contact with ideas. Firstly, he took his personal devotion very seriously, especially on reaching middle age. In 1894, during Lent, he subjected himself to a complete fast and was confined to bed. By then his fame as an architect was such that the local newspapers carried reports of his progress. In addition, accounts suggest that his conservative views could also be critical and his personal austerity, combined with his benevolent concern for the poor, prompted a critical stance of the Church.

Thus Gaudí’s own independent thought serves to remind us that it was in his workshop with his architects and craftsmen that he designed, forged and carved his response to theology as well as to the nationalistic concerns of Catalan culture.