Читать книгу Antoni Gaudí - Jeremy Roe - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

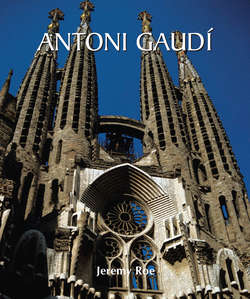

Perspectives on the Life of Antoni Gaudí

Gaudí’s Character and Thought

ОглавлениеHowever, Gaudí’s belligerence is one dimension of his character, and while it indicates his sense of self-worth it tells us less about his architecture. One of the defining aspects of Gaudí’s style is his imaginative response to the forms and styles of architectural traditions. Through juxtaposition, transformation and reinvention he would employ architectural motifs and styles in original and creative ways in his mature work.

The School of Architecture provided an intellectual and ideological context for Gaudí to begin thinking along these lines, in terms of the latest theories of architectural practice. These themes provide a key perspective to understanding the development of Barcelona’s particular brand of European modernism.

Gaudí’s own thoughts and opinions need to be discerned from his actions and associations with his contemporaries. Unfortunately, the existing correspondence is limited and Gaudí was not inclined to turn to writing as a means of expression. He stated in 1913 that,

‘Men may be divided into two types: men of words and men of action. The first speak, the latter act. I am of the second group. I lack the means to express myself adequately. I would not be able to explain to anyone my artistic concepts. I have not concretised them. I have never had the time to reflect on them. My hours have been spent in my work.’

Although statements by artists, architects, composers and writers as well as other public figures need to be read with a critical attention to detail, this statement contains more than a grain of truth. Firstly, except for some youthful writings produced between 1876 and 1881, Gaudí demonstrated no concern to theorise his architecture.

11. Gaudí’s Writing desk.

Nor did he become a teacher in the academic or university sense, except in the very practical sense of instructing and working alongside his team of assistants, fellow architects and other craftsmen.

Secondly, Gaudí never allowed himself enough time away from the many projects he worked on to analyse the ideas that shaped his working practice.

However, there are a scattering of statements from Gaudí from the final decade of his life which, together with the early writings, offer suggestive insights into his buildings, as will be seen later.

A curious autobiographical statement by Gaudí is the desk that he designed and had built for himself in 1878. It is one of the few objects in his whole oeuvre that combines a personal written statement with drawings.

Unfortunately, the desk itself is only known through photographs. The desk is a refined advertisement of his skills as a designer, in which capacity he would soon undertake a number of commissions. It also shows his interest in combining decoration with architectural elements.

In his writing he provides a detailed account of the many elements that made up this desk, such as many animals, plants and other organic forms. An important principle for combining decoration with the structural elements of the desk is explicitly made in his description of it:

‘It frequently occurs that when ideas are combined with one another they diminish and are obscured. Simplicity gives them importance.’

Even in the complexity of the Sagrada Familia, Gaudí’s ability to maintain dialectic between simplicity of form and the richness of his ideas would be upheld.

Gaudí certainly appears to have been consistent to the few principles he did clearly state.

While his architectural skills were being learnt, tested and refined Gaudí swiftly made the transition to the customs and fashions of Barcelona and its student community. Anecdotes record Gaudí’s well dressed and manicured image during his student days.

The extra paid work he took on was perhaps encouraged by the social pressures to maintain this fashionable image, and it seems probable that a coppersmith’s son would feel proud to be well dressed.

Gaudí’s sartorial elegance has been subjected to critical scrutiny by biographers for the contrast they offer to his later ascetic life.

However, the fact that he discarded the suits and dressed in a humble manner is more significant than the fact that he wore them and the best indication of what Gaudí would become is best shown by his dedication to work.

In addition, personal appearance would have been influential in making his way in Barcelona society, especially amongst his prospective patrons.

Gaudí’s 1878 design for a business card is worth noting in this regard too. The elegant art nouveau script with the floral flourishes on the letter ‘A’ is a subtle promotion of his skills.

The friendships and professional relationships Gaudí made show how his skills and intelligence were swiftly recognised in Barcelona. He designed a house for his close friend and medical advisor Dr. Santaló.

In comparison to the more rigid class system of Britain it is interesting to see how the son of provincial boilermaker could strike up a relationship with one of Barcelona’s wealthiest men, Don Eusebio Güell.

Statements by Gaudí about Güell suggest the relationship was marked by deference on the architect’s part, yet they shared common interests in the culture and heritage of Catalonia, and of course, in architecture.

12. Finca Güell, Entrance gate column detail.

13. Finca Güell, Wall tile detail.