Читать книгу Antoni Gaudí - Jeremy Roe - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Perspectives on the Life of Antoni Gaudí

Оглавление2. Portrait of Gaudí

The life of Antoni Gaudí (1852–1926) is best told and analysed through a focused study of his works. The buildings, plans and designs testify to Gaudí’s character, interests and remarkable creativity in a way that research into his childhood, his daily routines and working habits can illuminate only dimly.

In addition to this, Gaudí was not an academic thinker keen to preserve his thoughts and ideas for posterity through either teaching or writing. He worked in the sphere of practical, rather than theoretical work. Were this not enough to challenge attempts to gauge the mind of this innovative architect the violence of Spain’s Civil War resulted in the destruction of a large part of the Gaudí archive, and this has denied a deeper understanding of Gaudí the man, his character and thoughts. On 29th July in the first year of the Spanish Civil war the Sagrada Familia was broken into, and documents, designs and architectural models stored in the crypt were destroyed.

The absence of documentation limits the possibility of a searching biographical study, and it has encouraged rather more speculative interpretations of the architect. Today Gaudí has gained an almost mythic status in the same way that his buildings have become iconic. While his work continues to attract the ‘devotions’ of many thousands of tourists, his life inspires a range of responses. Besides the academic scholarship of Juan Bassegoda Nonell, for example, or the recent biographical study of Gijs Van Hensenberg, the life of Gaudí has prompted hagiographies and more imaginative reflections. In a different vein Barcelona’s acclaimed opera house, el Liceu, premiered the opera Antoni Gaudí by Joan Guinjoan in 2004 and this process of cultural celebration has taken on a metaphysical dimension with the campaign by the Associació Pro Beataifició d’Antoni Gaudí to canonise him.

The ongoing celebrations and constructions of Gaudí the man by various groups signals how in our ‘Post-Modern’ age the ascetic, inspired, untiring creator remains a key trope of creativity in the popular imagination. Gaudí remains an enigmatic figure and attempts to interpret him tend to tell us more about the interpreter, as is illustrated in the following quotations.

Salvador Dalí records an exchange with the architect Le Corbusier in his essay As of the Terrifying and Edible Beauty of Modern-Style Architecture. Dalí stated, “…that the last great genius of architecture was called Gaudí whose name in Catalan means ‘enjoy’.”

He comments that Le Corbusier’s face signalled his disagreement but Dalí continued, arguing that “the enjoyment and desire [which] are characteristic of Catholicism and of the Mediterranean Gothic” were “reinvented and brought to their paroxysm by Gaudí”. The notion of Gaudí and his architecture with which the Surrealist confronted the rational Modernist architect illustrates a recurring feature in the historiography of Gaudí, which is the concern to isolate Gaudí from the specific history of architecture and render him as a visionary genius.

Furthermore, Dalí’s account aims to place Gaudí in a pre-history of Surrealism and identify Gaudí as a ‘prophet’ or precursor of the aesthetics and ideas of that avant-garde Modernist movement.

While the devout Catholic and studious architect Gaudí may have considered anathema much of Dalí’s art and writing, he may not have disagreed entirely with Dalí’s comments cited here.

However, it should be noted that to identify Gaudí as a proto-Surrealist risks obscuring Gaudí’s intellectual position, as well as his traditional religious beliefs. Considered from an historiographical angle Dalí’s statement suggests an insight into Gaudí’s continued appeal into the early twenty-first century. It may be argued that the frequent reappropriation and ‘reinvention’ of past styles in contemporary art, fashion and design has helped shape the appeal for Gaudí’s artistic reappropriations, what Dalí termed his “paroxysm of the Gothic”.

It is of the utmost relevance to note that Le Corbusier was by no means antipathetic to Gaudí. In 1927 he is recorded as saying, “What I had seen in Barcelona was the work of a man of extraordinary force, faith, and technical capacity. Gaudí is ‘the’ constructor of 1900, the professional builder in stone, iron, or bricks. His glory is acknowledged today in his own country. Gaudí was a great artist. Only they remain and will endure who touch the sensitive hearts of men…”

As will become apparent, Gaudí would have probably shared Le Corbusier’s sentiments more than Dalí’s. Le Corbusier’s criticism signals a different approach to the analysis of Gaudí’s work. It is examined in the specific context of architectural history.

In the course of this book, analysis of Gaudí’s buildings seeks to balance the measured architectural analysis evoked by Le Corbusier with discussion of the shifting critical responses to Gaudí’s work such as Dalí’s. The foundation for this approach is a critical understanding of Gaudí’s life. His interests and the society of Barcelona, which shaped his work in important ways, need to be considered and they are the subjects to be treated. It needs to be emphasised that in the absence of further information it is the buildings which are the best testament to the man.

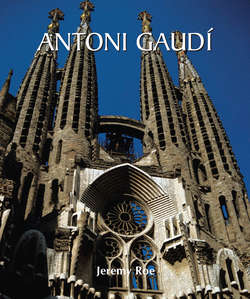

3. Temple of Sagrada Familia, New towers of the Nativity façade.