Читать книгу Antoni Gaudí - Jeremy Roe - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Perspectives on the Life of Antoni Gaudí

Gaudí’s Childhood

ОглавлениеGaudí was not born in Barcelona, the city that provided a key cultural dynamic to his architecture, but he was born in Catalonia, in the small town of Reus. Biographers of Gaudí, often prompted by the architect himself, have identified in his provincial childhood experiences the origins of his later creativity. The belief that art may be an inherited gift underpins Gaudí’s assertion that his “quality of spatial apprehension” was inherited from the three generations of coppersmiths on his father’s side of the family, as well as a mariner on his mother’s side. Whatever truth there may be in Gaudí’s claim, we can be certain that his home life was comfortable and stable. The only shadow cast over his childhood was a period of severe illness. The psychological effects of this on the development of the young child’s imaginative faculties and spiritual convictions are hard to gauge, although his survival may be read as an early sign of a strong constitution and defiant determination.

It can be asserted with more confidence that this period of Gaudí’s life introduced him to four factors that would be fundamental to his career: an interest in architecture, especially the Gothic; Catalan history and culture; Catholic doctrine and piety; and, finally, the forms and colours of the natural world.

In many ways architecture acted as a medium to explore and reflect on the latter three. Besides the traces of Reus’s medieval heritage the neighbouring towns and countryside provided a number of important buildings to visit, such as the famed pilgrimage Church of Montserrat and Tarragona’s impressive cathedral.

Gaudí’s experiences of such places would have been coloured by an awareness of them as the cultural patrimony not of Spain, but the region of Catalonia, of which Barcelona is the capital. Catalonia had once been part of the independent Kingdom of Aragon, which first became linked to the Kingdom of Castile to form what we know as modern Spain in the fifteenth century. The process of balancing unification with regional autonomy is still being negotiated today and as a result Catalonia has developed a strong sense of national identity, with Barcelona at its centre.

The fact that many of the buildings Gaudí visited were religious is a reminder of the particular role that religion played in the construction of Catalan identity, as it did in the histories of other regions of Spain. As an adult, Gaudí would identify with both a defiant form of Catalan nationalism and a devout commitment to the Catholic Church. However, as a child and youth such serious concerns were a long way off.

Nonetheless, a keen youthful interest in architectural history and a concern for Catalan patrimony provided a foundation for his later ideological position. Besides visiting existing buildings Gaudí, accompanied by friends, would also seek out the ruins of once-great buildings and the traces of Catalonia’s history. It would not seem fanciful to suggest that these excursions into the countryside inspired in Gaudí a creative vision of the landscape, stone, plants and other elements of the natural world. There is little verbal testimony of Gaudí’s youthful attitudes to nature, and we must wait to examine his architecture to gauge this aspect of his thinking.

However, the clearest identification of the early signs of Gaudí’s creative and intellectual powers are exemplified by an important episode from his youth, his involvement in a project to restore the ruined Cistercian monastery of Poblet.

4. Episcopal Palace of Astorga, General view of façade.

5. Finca Güell, Ladon, the guardian of the Gardens of the Hesperides (dragon detail).

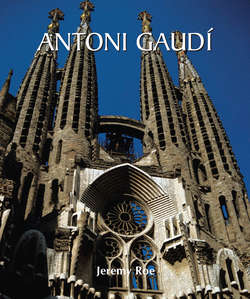

6. Temple of Sagrada Familia, Sculptures on the old façade.

In 1867, accompanied by his childhood friends Eduardo Toda and José Ribera Sans, Gaudí visited the ruins of the twelfth-century monastery. Documentary evidence of their visits records their imaginative impressions: the Manuscrito de Poblet, written by Toda in 1870, lists their plans to restore the crumbling remains into an utopian cooperative, attracting the necessary labour force as well as a community of artists and writers, the combination of which would restore the monastery to a new life.

However, their youthful spirits were captured by the monastic ideal with art, life and pleasure as guiding principles, rather than by the restoration of Catholic tradition. It is worth noting that the Manuscrito de Poblet records the first known drawing by Gaudí of the heraldic shield of Poblet, which was produced in 1870.

In the 1930s Toda would return and lead the restoration of this monastery, but by that time Gaudí had been dead for four years. The intervening years had been spent by Gaudí not simply in imaginative restorations of the ruins, but in a creative and innovative interpretation of the architectural language of the past, as well as its values. It was as a student in Barcelona that this artistic process was initiated in earnest.

7. Student Drawing of Lake Pier.