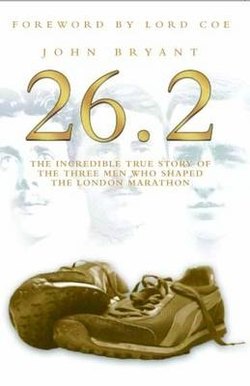

Читать книгу 26.2 - The Incredible True Story of the Three Men Who Shaped The London Marathon - John Bryant - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление– CHAPTER 2 –

A TASTE OF DEFEAT

In spring 1902, Wyndham Halswelle’s affair with the running track came to an abrupt end. He and his regiment were packed off to South Africa, where Lord Kitchener was mopping up the war. Here, he was to get his first taste of action.

Once again, Wyndham was a six-year-old drilling his tin soldiers on the lawn, taking on the enemy face to face in single combat as he had done in his playground fantasies. Life at the front, though, turned out to be very different. There were huge periods of inactivity while he would kick his heels waiting for the chance to be a hero, but there were other opportunities to play the hero on the playing field or on the running track.

When Halswelle landed in South Africa in 1902, he just caught the end of that strange business, the Boer War. The Boers, who were the off-cuts of Dutch colonialists, were keen to fight for their independence from Britain but they were not so keen to bring the benefits of democracy to those who had descended on this part of the world in search of gold and diamonds – the get-rich-quick merchants. Certainly, they were completely against any idea of extending the franchise to the black population, the indigenous people they found in the land in which they made their home.

As soon as Halswelle moved with his regiment, the Highland Light Infantry, towards the front, he found that the fighting had descended into a messy guerrilla conflict. He was keen to fulfil his dream of getting a taste of the action but his vision of himself was as a soldier, someone who would take on an opponent in a fair fight man to man, face to face. This war was baffling to the young soldier; it was a dirty war.

Wyndham Halswelle had been brought up with a code of chivalry that was remarkable for its lack of realism. Fellow troopers would talk of snipers and the guns that could deliver death without the giveaway trail of smoke emitting from their own British rifles. Given half a chance, they would say, these Dutchmen will shoot you in the back.

Life outside the city of Bloemfontein was a mixture of infrequent fighting and unbearable boredom. The troops would arrange spontaneous cricket and football matches, picnics, fêtes and parties. They weren’t always peaceful either, for there was plenty of drink around. Fights would break out, and gambling, which could land you on a charge, was rife. There was no shortage of women or civilians around the block houses and tented camps. Plenty of men had wives and children back in Britain, but that never stopped them from picking up the women around the camp.

Halswelle shone at cricket and football, though rugby, his chosen game, was not popular among the men. Almost every morning, he would be found running around the camp to keep in shape and a lot of his off-duty hours were spent complaining about the nature of the war and the conduct of the Boers.

His daydreams at Sandhurst invariably had him facing hordes of fanatical natives or the disciplined ranks of crack European troops. There was glory in that daydream. But Halswelle and his fellow officers shared their doubts and sometimes contempt for the Boers, who, though God-fearing, did not shape up as an acceptable enemy. They were scruffy and had no professional army as such; often they wore no uniform either.

Plenty of men in the regiment knew of Halswelle’s reputation as a runner.

‘Why don’t you take a race here?’ they would ask, but Wyndham seemed wary of racing far from the organised meetings he had known back in Britain. He would watch and shake his head at the sight of a few men toeing a line scratched in the dirt, then barging their way to the finish.

This was never quite the way it was at Sandhurst, where the track was marked out with painted white lines on firm grass, measurements were accurate and the starter controlled everything. You ran to orders there, but here the course was a roughly paced-out distance over hard, dusty, uneven ground. Close to the battlefront there was no finishing tape, no fancy running, and nowhere to dig decent holes for your spiked shoes on the starting line. But when the requests to run turned to taunts, Wyndham thought again. Perhaps he might race there, after all.

His appearance on the track was enough to stir groups of soldiers to watch him in action. They knew this tall, muscled, slightly tanned man, whose white vest contrasted with the reddening of his skin, had been a champion; his very appearance could cause a ripple of excitement. It was not that often you got the chance to see a runner of his calibre in action. You could only guess what was likely to happen when a man like this toed the line.

If there is one thing that excites spectators, it is the chance to witness a champion performing, asserting his dominance with power and authority. But they can be excited, perhaps even more so, by the prospect of seeing a champion, a certainty, toppled and humbled by a dark horse. The bookmakers love to see that too, and some of the officers remembered the time back at Sandhurst when even the mighty Halswelle tripped and fell hard on the track.

Gambling always seemed to be in evidence whenever such impromptu race meetings were organised by the regiment in South Africa. ‘Evens on the field,’ the bookies would murmur, and the murmur would breeze around the camp. Of course, they shouldn’t have been there, for betting was strictly prohibited. But when it came to gambling or taking prisoners, you could always find an officer who seemed blind or deaf. It was difficult to stop a trooper from putting a handful of shillings on a runner they fancied, or a race where they seemed certain of the outcome.

Win or lose, this was the chance to see a gifted runner in action. Where, they wondered, did he get that extra ingredient that makes one athlete dominant? Sometimes technical differences make a champion – some wear spiked shoes, others dig starting holes, while cork grips may be strapped to the hands with elastic bands, for there was a theory that sprinters ran faster if they had something to grip onto.

But none of these techniques accounted for Halswelle’s superiority. Whenever he lined up for races, he looked preoccupied, aloof almost; slowly and silently he moved to the start. But even here, so far from Sandhurst, one sensed the starter’s orders would spark an explosion.

‘Strip out, gentlemen, please!’ came the booming command. The crowd would hush, waiting to catch a glimpse of the eight or nine figures crouching to strain for the first smoke of the gun that would pitch them forwards like shots from a sniper. For a moment, they would be frozen and the stomachs of the spectators would flutter as they held their breath, waiting to witness the young, fit men fighting to get the better of each other in this trial of strength, speed and will.

Then they’d be off, with some heavy-footed and making fierce noises as they moved, others staying too long in contact with the South African soil between strides. Their facial expressions were quite extraordinary too. Teeth were clenched in ferocious or agonised grimaces. Some looked as though they were snarling. Heads would be thrown back or jerked to one side; arms thrashed wildly instead of pumping in time with the legs. Energy would be spent recklessly as torsos rocked and twisted. It was like watching men trying to grab a lifeline just out of reach.

But when Halswelle came out of the holes he had scraped at the start, he was a revelation. You could see that he had a gift, that he ran with fire in his belly. Once he took off, he seemed to gain a yard or two just by starting.

It was hard to believe that a man could fly into action so quickly. There was no slow build-up, no hesitancy, no changing of gear. Ruthlessly, smoothly, the legs produced a stride that could cut through the opposition like a sword on the battlefield. The body was steady, the face showed no strain. Arms and legs moved forward with no sideways sway; the head looked as though it were floating, with no rise and no fall – it was all poise, pace and purpose.

Like an arrow snapped from a bowstring, he reached towards a finish that wasn’t just a simple piece of rope between two posts but a declaration of his rightful place as a champion. For other runners a race was fun, a gamble, a game – maybe a way to a prize – but to Wyndham Halswelle it was a declaration of his identity.

‘By God,’ one of the troopers muttered, his eyes shining as he watched him run, ‘he’s got class!’ But even as he ran, the gambling men, those who had taken the illicit bets, knew what was to come.

As Halswelle eased ahead, one man clawing his way down the track stretched forwards a hand and clipped his trailing leg. Suddenly, the beauty of the arrow that seemed to be heading straight for the target was thrown off-course. Halswelle tripped, one leg smacked against the other, then he lurched. It was his own speed, his own purity of motion, that brought him crashing down.

He fell heavily, his hands scraped red raw by the sand. His knees, from which the blood dripped, left stains where the blood met the dust of the veldt. Halswelle shook his head in anger: he had been way in front and the other runners knew it, but he had been robbed. It was enough to make him want to throw the whole thing in.

Looking down at him was a trooper shaking his own head in disbelief. The man who hauled Halswelle to his feet that day was a squat, tough-looking member of the regiment with an accent that reeked of the borders between England and Scotland. His name was Jimmy Curran.

‘You need to learn a thing or two, sir,’ he said, looking down at the fallen man. It was a meeting that was to change both their lives.