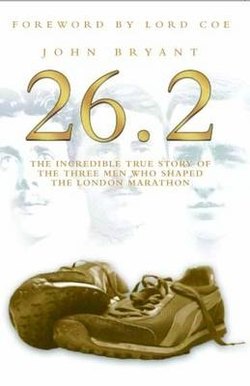

Читать книгу 26.2 - The Incredible True Story of the Three Men Who Shaped The London Marathon - John Bryant - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление– CHAPTER 5 –

THE STAMP OF LOVE

Dorando Pietri’s sporting career was almost over before it began. Always a boy of sudden enthusiasms, and ever eager to follow the latest fashion, he had simply fallen in love with cycling. He had seized on bike racing as a way to make his mark and be somebody, as a route to success and standing in Carpi. The seductiveness of the machines, the scent of the oil, the bright clothing, the cut of the racing jerseys, the way his heart beat when lining up for the start – he loved it all. He also enjoyed talking about the sport and reading about it in the papers after a race.

The members of La Patria were enthusiastic supporters of this infant sport. They pointed out that it was healthy as it got you outdoors and just about anyone could do it. Newspapers such as Luce gave plenty of space to cycling too. Their editors reckoned the bicycle was a way of emancipating the working classes in northern Italy, where the poor had been forced to spend hours trudging their way to work from their homes and hamlets outside the cities. Now, because of the bicycle, they could reach their places of work quickly and cheaply. For Dorando, the bike was far more than just a cheap way to travel: it gave him speed and a way to prove that he too could be a champion.

A particularly dangerous form of cycle racing, especially in the early years of the twentieth century, was a ride paced by motorbikes, as neither they nor the bicycles were up to much mechanically. But Dorando was certainly keen on the sport – it all seemed so wonderful at the time. He savoured the moments at the start of the race when he was held motionless in the saddle, his head dipped deep over the handlebars, while the motorbikes coughed and spluttered their way into life.

‘They’ll pace you, they’ll shelter you,’ his friends shouted at him. ‘All you have to do is ride till you drop – you’ll move faster than anyone could dream.’

In mid-August 1904, Dorando found himself in a two-man race behind men perched on two 2.5 horsepower Peugeots. Once he got going, the feeling of speed was sensational, as if men had never gone this fast but now you could do it all under your own power. The closer you could get to the motorbike in front, the more you would benefit from the shelter and the faster you might go.

Inevitably, with the crude machines of the time, trouble was waiting around every corner, and on the fifth lap of this 25km race, Dorando clipped the back of the pacing motorbike. Both riders were sent sprawling and he was taken to hospital. Luckily, although he was covered in blood and scrapes and was bruised through to the bone, nothing was broken. Even so, he was a painful mess and remained in a hospital bed in Modena for eight days.

The experience gave him plenty of time to think. Maybe his friend Tullio was right after all and he should give up cycling. Perhaps he should see if he couldn’t make his mark as a runner. They had been saying he was in the wrong event, so maybe the bruises were telling him something.

There were other reasons, too, that made him uneasy about bicycle racing. He had read about men who could push their body way beyond all human endurance – a thought that excited him, but he had also heard about some of the methods they used to tap these powers. After all, the great cycling boom was already sweeping Europe and a man might win fame and a sizeable fortune because of his powers on a bike. Why waste your life labouring or down the mines if you could earn far more this way? And already there were trainers haunting the racing circuits to show how it might be done.

One such man was Choppy Warburton, an English impresario and trainer who operated like a Svengali whenever there were big prizes to be won. His men would sometimes finish glassy-eyed and semi-conscious, almost living corpses, but still somehow they would find the strength to win. Warburton would goad them to even greater efforts and, as some sharp-eyed spectators noted, he would sometimes pull a mysterious bottle from his greatcoat pocket and encourage them to drink from it.

His face half-hidden beneath a Derby hat, and always wrapped in a huge black overcoat, Warburton exuded a great air of mystery. Many spectators reckoned his methods were all hocus-pocus, a crude form of psychology, but others thought the little bottles contained some of the most powerful drugs known to man at that time – a mixture of strychnine to stimulate the body and morphine to kill pain. For these cyclists, taking the stuff was a matter of life and death because so much money was at stake.

There were many deaths from cycling in the two decades from 1890 to 1910, some cyclists dying in the saddle and others shortly afterwards, and eventually Choppy Warburton was warned off every cycling track in Europe. But he was not the only such trainer and the life expectancy of racing cyclists at the turn of the century was terrifyingly low. The cyclists were said to have died from exhaustion and fatigue, but in fact, they mostly died from abuse to their bodies.

Dorando had no wish to kill himself and he believed that there was no stimulant that could match his own burning desire to win applause and acclaim for his races. So, after his accident and, weeks later, the incident when he matched strides with Pagliani in the piazza, he switched his passion from cycling to foot racing.

Within three weeks of that exhibition in Carpi, he was lining up for a 3,000-metre race in Bologna. There, on 2 October 1904, in his first official race, he came second to Aduo Fava, and in the weeks that followed he would take on races and distances wherever he could find them. A week later, in fact, he got his name in the record books when he captured the Italian record for covering almost 9,000 metres in half an hour.

More races followed. He would take on anything between 5 and 15 miles, and during October and November, Dorando found that he was winning most of his races. Luce, which had given over so much space to cycling coverage, suddenly started to allow a few more column inches to the exploits of the runner Dorando Pietri.

Dorando would make sure that his father saw the press reports, pointing them out with excitement. ‘You see,’ said Desiderio, ‘you might not be so keen to leave this place after all.’ Besides, there was now another reason for his son to stay in Carpi.

Teresa Dondi was a shy, delicate girl with large eyes, who looked younger than her years. There was something still and contemplative about her face, though her movements were quick and impatient. She was, in fact, just a few months younger than Dorando. Her father was a share cropper, a tenant farmer of sorts, and certainly not wealthy but still a few notches up the social scale from the Pietri family. She had caught the eye of Dorando’s boss, Pasquale Melli, who saw that she was bright as well as pretty. He had offered her some work, to act sometimes as a maid at his home and occasionally to help out if she were needed in the shop.

Dorando first ran into her at the confectioner’s and he couldn’t take his eyes off her. Teresa was nervous and coltish; she moved quickly, almost jerkily, and whenever she reached up to pluck a box of chocolates from a shelf, the glimpse of lace beneath her overskirt produced a feeling in his legs and stomach that he had only ever known before the start of a big race.

He fluttered uncontrollably and was tongue-tied, but although neither of the pair could find the words, both knew there was much to be said between them. They were inseparable – the girl next door, so shy and so young, and Dorando, the boy who was winning a reputation to be proud of because of his other passion, for running. For as long as they could, they kept their friendship secret. But others could see, from the looks that lingered too long, what was going on.

Teresa’s mother would squint through the shutters, looking out for the messenger boy.

‘Look at his clothes,’ she would say to Teresa. ‘Why do you bother talking to someone like that? He’s poor and he’ll always be poor.’

Teresa’s eyes would swell with hot tears, and she bit her lip when her father told Dorando to stay away from her.

But Melli’s family, the owners of the shop, liked the girl. ‘Where’s the harm?’ said Melli, and so the lovers would snatch forbidden time together, keeping their secrets. Teresa was so proud of Dorando – she loved to see his name printed in Luce and she could see how happy that made him. She let him touch her and kiss her, and only the blushes would make him pull back, and he ached whenever he was away from her.

‘If I can be a champion, maybe it will help me to a fine job,’ Dorando would dream. ‘They know all about me at the hat factory – perhaps there’s something there for me.’ Teresa let him dream on.

Dorando certainly made sure that his dream of Teresa didn’t die. One morning, when he was away in Turin doing his national service, Teresa received a picture postcard. It was addressed in a neat copperplate hand to Gentil Signorina Dondi Teresina, Via S. Giovanni, Carpi. On the front was printed, ‘A thought from Turin’, and it carried a picture of a flower against the background of the city’s main railway station. There was no message, no greeting and no signature. Teresa looked at the card with a blush and a shrug. Twenty minutes later, she was at the Melli home, alone in the kitchen with the kettle steaming and trembling on the hob. As the steam softened the paste on the stamp, she gently peeled it off.

There, written in a tiny hand for her eyes only, was a message: ‘This is Dorando writing to remind you that he loves you, please forgive me for what happened when we were last together.’

Teresa read it again and again, and kept the card beside her until her dying day.