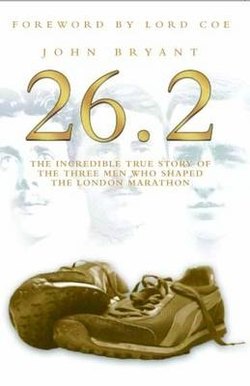

Читать книгу 26.2 - The Incredible True Story of the Three Men Who Shaped The London Marathon - John Bryant - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление– CHAPTER 1 –

ONCE A WINNER

Wyndham Halswelle peeled off his shirt and twisted it between powerful hands until the sweat splashed dark patches like blood on the parched, dusty track. He smiled at the man screwing his eyes up at a watch.

‘I can win this, even here,’ he said. ‘About the only thing that can stop me is a bullet in the back – I can beat them all.’

‘You can,’ said the trooper, ‘but it’s not the Dutchmen you’ve got to worry about, it’s the men who line up alongside you.’

Wyndham Halswelle, young, strong and a soldier, knew all about winning; it had filled his life for as long as he could remember. He searched for the smell of it, the secret of it everywhere. He saw the prospect of winning on the flags of armies, in the stride of an athlete, in the courage of a statesman and in the physical perfection of a warrior.

Halswelle was born on 30 May 1882, at No. 4 Albemarle Street, Piccadilly, in the heart of the great British Empire. He was born into a city that seemed to rule the world, a city full of energy that could inspire great literature and a tumult of ideas. Here was the Westminster that laid down the laws that echoed around the world. But here too, just a few miles to the east, was Whitechapel, home of Jack the Ripper, where a man might tear your life and your dreams apart under the cover of darkness.

Halswelle’s father was an artist and a prosperous one. His mother, Helen, came from a traditional army background. She was fiercely proud of her grandfather, Nathaniel Gordon, a major general in the Indian Army, who carried his scars and his medals with pride.

There was much talk of military tradition, of Scotland and of his father, Keeley Halswelle, who earned his living as a watercolourist and had exhibited in London and Edinburgh. Keeley travelled frequently to Paris and Italy, looking for the light and for inspiration. He was an associate of the Royal Academy and when he died in Paris in April 1891, his estate was valued at around £2 million in today’s terms.

As a child, Wyndham looked up to his mother, that fierce upholder of the family military tradition. Mama always said he would be a soldier. Born in London, he wrapped himself in his Scottish heritage. Occasionally he would play with his older brother, Gordon – christened with the family name that his mother admired so much – but from the age of five, Wyndham lived in a world of his own. He was forever playing soldiers.

On the days when it rained, he would manoeuvre his armies of tin soldiers in the drawing room of the family home in Richmond. Then, whenever the sun shone, he would be out in the garden or the park, marching and drilling his brother and his imaginary troops on the well-kept lawn there. Sometimes he would sport the uniform that his mother had bought for him. He dreamed his dreams and nothing in or out of school so preoccupied him as tales of chivalry and knights fighting in single combat.

As a teenager, Wyndham was strikingly fluid. He moved with an animal grace and the languid, loose-limbed lilt of a cricketer. At school, the younger boys were mesmerised, hanging around him and hero-worshipping him a little, drawn by his magnetism and his athleticism. They would do anything for him and would quarrel over who would scrape the mud from his studded boots, who would massage the grease into the soft leather of his running spikes.

The mothers of other boys who visited the school would smile at his easy good looks and his cascading blond hair. By fifteen, he was winning all the foot races at school, but as his schooldays drew to a close, he was excited by the rumblings of the war to come in South Africa, a war that would test and harden the soldiers of the Queen in battle.

Young Wyndham longed to get out of Charterhouse School and into Sandhurst, Britain’s Royal military academy, where he could train to be a real soldier. His greatest fear was that the war would be over by Christmas; he ached for the chance to fall in with the others tramping off to the troop ships to the haunting marching tune of ‘Goodbye Dolly Gray’. When he signed up for Sandhurst at his mother’s insistence, his father struggled with his own disappointment that his talented boy would cut himself off from his artistic side. But Keeley Halswelle understood that most young men were only interested in war, young girls and sport. For Wyndham, the world was just awakening and he was interested in all these things.

Photographs were rare enough at this time, but one captured the young Wyndham caught between school and the military academy, showing his youthful spirits, vaulting with a grin over his sister-in-law Ethel. Another caught him long jumping over a wheelbarrow on those well-trimmed lawns in Richmond.

Halswelle was determined to demonstrate to his father that he could achieve things in the world on his own account, that he too could be a winner. And to do so he did not have to prove himself, either in the artistic studio of his father or in the regiment of his mother. Sport was his canvas: he would win his races and he would remember with a smile the admiring knots of schoolboys cheering his victories and saluting his triumphs.

That summer, as the war in South Africa warmed up, he gave his father a glimpse of the different kind of artist that he himself could be – an artist on the track. At Sandhurst, the admiring schoolboys were now replaced by senior officers who recognised, however fleetingly, that they were being seduced by the magic of a man in motion. For Wyndham Halswelle really could run. Even among fine sprinters, men who fancied themselves as quick movers and who were so fancied by others, this was an exceptional man.

A boy like that, the officers would say, needs a trainer, someone to show him how to be a great champion. Such men existed, but mainly across the Atlantic, where the New World’s first athletic coaches were already issuing orders to their well-drilled squads and where they reckoned that men like Halswelle lacked the killer instinct. In England, they would say, they churn out good losers but there’s no such thing as a good loser – it’s kill or be killed. In sport it is always the winning that matters. But for Halswelle running was about far more than just winning, it was an expression of the human body, of rhythm and grace, strength and belief. He loved to win, of course, but for him the satisfaction was to do it on a level playing field in an even contest.

Sometimes he would share his philosophy of winning with his friends at Sandhurst. They would smile over a drink and a cigar, and the soldiers would joke that all this talk of fair play would someday be the death of young Halswelle.