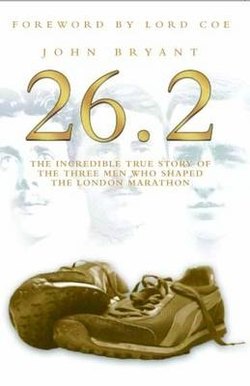

Читать книгу 26.2 - The Incredible True Story of the Three Men Who Shaped The London Marathon - John Bryant - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление– CHAPTER 6 –

CHEATING FOR BOYS

There is a copse behind the solid Victorian buildings of Charterhouse School, near Godalming in rural Surrey. It’s where generations of boys from the school, free from the shackles of classroom rules, could run a little wild and indulge their dreams and fantasies. It was here, as Wyndham Halswelle’s mother constantly reminded him, that you could find the first playground of a boy who went to the same school: the soldier, hero and role model of every schoolboy in the Empire – Robert Baden-Powell. They were, as she so often mentioned in her letters, old boys from Charterhouse.

The acts of ingenuity, courage and resourcefulness of Baden-Powell during the seven-month siege of Mafeking during the Boer War were followed in every detail throughout Britain and the Empire, and made a deep impression on Halswelle. Beyond that, the philosophy and ethos that Baden-Powell carried over into the Boy Scout Movement captured the imagination of generations of schoolboys to come.

Baden-Powell never really shone much at school subjects but he thrived at Charterhouse, where the public school ethos of cheerful courage under pressure, loyalty to the team and playing the game, which was already fuelling the armies of the Empire, suited this energetic sportsman, artist and actor.

‘The whole secret of success in life is to play the game of life in the same spirit as that played on the football field,’ he was fond of telling his audience of boys.

When war was declared in South Africa, Colonel Baden-Powell and 1,000 men were left to defend the town of Mafeking, which was the supply centre for the British. The town’s success in surviving the longest siege in that war, from October 1899 until May 1900, without any real loss of life, would in any case have elevated the name of Baden-Powell to the status of an imperial symbol, the hero of an empire under threat. But it wasn’t just his ability to succeed, it was his capacity to do so with nonchalance and a taste for fun and adventure, using a combination of fake barbed-wire defences and Sunday baby competitions, that in the eyes of the British public turned him into the very epitome of pluck and team spirit. A master of bluff, Baden-Powell thought up all sorts of schemes to make it seem as if the town of Mafeking was heavily defended.

When ordered to South Africa, his task was to raise two regiments of mounted rifles and to use them to hold the Western frontier of the Transvaal, drawing Boer forces away from the British landings on the coast. With his men, he became trapped in Mafeking, 250 miles away from the nearest reinforcements. Almost immediately, he was faced with a Boer force four or five times greater than his own and while they must have expected a quick and easy victory, they were to be disappointed.

As well as digging a strong set of defensive earthworks, Baden-Powell missed no opportunity to trick his opponents about his strength and intentions. Imitation forts were built, complete with a prominent flag and flagstaff to draw the fire of the enemy. Not only this, but he issued orders for non-existent assault troops attacking at night. He used a tin megaphone to make sure enemy sentries heard him and he managed to rouse the Boer camp while his own men got some sleep. He also improvised a searchlight and managed to con the Boers into thinking that all his forts were equipped with a searchlight.

One of his best schemes was to have a lasting significance. He recruited a bunch of boys to act as messengers and orderlies in order to release men to fight on the front line. This corps of boys was to provide the blueprint for the original Boy Scouts.

The Boers were sufficiently discouraged to abandon any hope of taking the town by assault, and settled down for a long siege. As the trench lines drew closer, a battle of snipers, as bitter as anything to be found on the Western front a decade and a half later, followed. But the siege was also a quite civilised affair: a ceasefire was observed every Sunday and the garrison amused themselves with concerts and cricket matches.

One day, a Boer gunner fired a letter into the town of Mafeking in an empty shell case, wishing that he had something with which to drink the health of the garrison. Baden-Powell immediately sent him a bottle of whisky under a flag of truce. Later, the Boer commander sent Baden-Powell a note that he and his friends were proposing to come into town and take them on at a game of cricket. Baden-Powell replied with panache: under the flag of truce he sent a letter that read:

Sir, I beg to thank you for your letter of yesterday. I should like nothing better after the match in which we are at present engaged is over. But just now we are having our innings and have so far scored 200 days not out against the bowling of Cronje, Snijman and Botha and we are having a very enjoyable game.

I remain, yours truly,

RSS Baden-Powell

But the tide of war was slowly turning against the Boers and eventually it was all over. The long-awaited relief column arrived on 17 May 1900 and helped Baden-Powell’s ragged defenders drive out the Boer forces. It was the end of a siege that had lasted 216 days at the cost of 212 killed and wounded. But Baden-Powell was a national hero and endowed with a celebrity he was later to build on as founder of the Boy Scout Movement.

Prompted by fears of imperial decline and fall raised by the Boer War, Robert Baden-Powell became increasingly concerned about the wellbeing of the nation, in particular that of young people. One report, published in 1904, claimed that out of every nine who volunteered to fight, only two were fit enough to do so. Physical deterioration and moral degeneracy became themes in many of the talks and speeches that Baden-Powell gave in the years that followed.

Soon he was exploring a ragbag of different schemes, mixing his experience of camping, woodcraft, military tactics and educational theories, and overlaying it all with his own vision of chivalry and empire. In August 1907, 11 months before the Olympics at Shepherd’s Bush in London, Baden-Powell conducted the famous Brownsea Island experimental camp. He wanted to test out the ideas he had been developing for his scheme of work for the Boy Scouts.

Modelled on his idiosyncratic vision of the hardy colonial frontiersmen, the ideal Boy Scout, disciplined and self-sacrificing, appeared as the culmination of a mythical lineage in British national history. He would embody the virtue and honour of the medieval knight and the stout-hearted courage of an Elizabethan explorer. The amount of energy that Baden-Powell expended in Scouting for Boys to encourage boys and men to hold the Empire together gives an indication of the level of British anxiety at this time, about both the state of the Empire and the state of the nation.

By 1900, Germany, the USA and Japan had started to challenge Britain’s leadership in terms of industrial production, and there were other threats to stability from within the British Isles, particularly from the newly organised Labour movement and the rise of the Women’s movement and demands for self-representation. Many chapters of Baden-Powell’s Scouting for Boys lay huge emphasis on the dangers of deterioration of the British race and the physical breakdown of the rising generation; he expressed contempt for the working-class ‘loafer’.

One area of British life seemed to embody many of Baden-Powell’s values – the public school playing field. The games ethic perfected by public schoolboys and their teachers seemed to mesh fluidly with the ideals of imperial service. To show loyalty to the group, to practise honour, to smile even in the face of defeat, this was the ethic that seemed to guarantee success in the colonies as well as embody the qualities of true masculinity. Baden-Powell regarded the public school playing field very much as the cradle of so many of these qualities, and drummed home the message that to do one’s best for the country was the way to succeed.

‘Get the lads away from spectator sports,’ he urged. ‘Teach them to be manly, to play the game whatever it may be and not be merely onlookers and loafers.’

In Scouting for Boys he adapted Henry Newbold’s resonant poem ‘Vitai Lampada’ (‘They Pass On The Torch of Life’, published during the war in 1897) into a Scout tableau retitled ‘Play the Game’.

The Gatling’s jammed and the Colonel dead,

And the regiment blind with dust and smoke.

The river of death has brimmed his banks,

And England’s far, and Honour a name,

But the voice of a schoolboy rallies the ranks:

‘Play up! play up! and play the game!’

Playing the game seemed to encapsulate the popular imperialism of the time and it was no wonder that it appealed to the young Wyndham Halswelle.

Baden-Powell certainly knew about winning. He was up for every trick of war, and was the first to pour scorn on the concept of fighting in bright, visible uniforms or to encourage using the cover of darkness, but always he managed to somehow combine this attitude with his own brand of British chivalry towards women, children and even the enemy.

‘As in sport, so in war,’ he said. ‘There is always room for chivalry when men fight fair.’