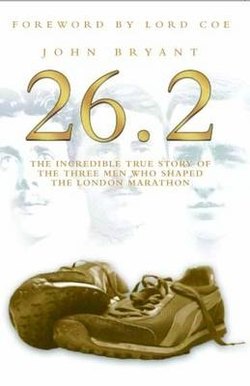

Читать книгу 26.2 - The Incredible True Story of the Three Men Who Shaped The London Marathon - John Bryant - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

DIGGING AND DREAMING

ОглавлениеThere was not a lot of time or room for chivalry in the rough, tough world of the Irish immigrant in New York at the turn of the century.

John Joseph Hayes was born in 1886 in Manhattan, New York. He was the son of Michael Hayes, born in September 1859, from Silver Street, Nenagh, County Tipperary. His mother was Ellen (or Nellie) O’Rourke, who was born in America but whose origins were in County Roscommon. The newly wed Hayes couple, Michael and Ellen, finally arrived on New York’s East Side to join the seemingly neverending procession of immigrants, with Michael hoping to find work as a baker.

The East Side of New York was Italy, Germany, Jewish Russia and Ireland in miniature. This was a melting pot and all the ingredients were there: those who daily fought poverty but still shared in the wealth of family support, enjoying the favours and help they could give each other, with each apartment building its own community, every block a village, every street a reflection of the country they had left behind.

It was not unusual for newly arrived immigrant families in Manhattan to occupy every inch of their cramped and run-down dwellings. Families of six or seven might live in one small room, then take on a boarder or two to help meet living expenses. Some lived in hallways, in basements or in alleyways – anywhere they could squeeze themselves in – and all too often the rents they paid were extortionate. Living and working quarters were often the same. A family would cook and eat in the overcrowded room where they made their living, and from the oldest to the youngest, everyone took whatever work they could find and did their part. Wages usually tottered at the brink of subsistence.

There was no margin for any error in the family budget, for survival could ride on a few cents. Day after day, the people of the lower East Side would grind out a living, working, saving and trying to move slowly ahead, and in so doing they would create a niche for themselves in the complex economic and cultural world of New York City.

It was in those circumstances, there in the railroad flats that once existed on the site of Tudor City, the site of slums and slaughterhouses, that Johnny Hayes grew up. There, local gangs thrived and could be powerful, but the local politicians could be even tougher too. The men from Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party’s bastion of corruption and power, knew that the Irish-American immigrants were like unformed clay and happy to be moulded in the ways of New York. And so they helped them to be a little more American, to feel a little more at home in their new world, and before long they were American citizens – and most of all, American voters.

The children of peasants – the shoemakers, bakers and so on who had been brave enough to cross the Atlantic – were not content to sit back and waste their lives amid the debris. What got them out of the slums and away from the clutches of the corruption that thrived during the 1890s was the determination to haul themselves up by their boot straps and to get out. To be an American was to climb into that great melting pot and to be poured out ready to take on the world as an American winner.

Johnny Hayes grew to be a small boy, but he was strong – strong enough to work while still a child, and he didn’t stay the baby of the family for too long. He was the firstborn, but was soon joined by another baby and then another. They were hungry mouths to feed, and Michael Hayes grabbed every hour to slave as a baker in the cauldron of the bakery at Cushman’s in New York. Soon even his 14-hour days were not enough and often he would bed down at the bakery, sleeping at the back in order to be up and ready for yet more overtime. Sometimes Johnny would join his father, earning a few more badly needed quarters long before he left his lost childhood behind him. ‘Heat never bothered me,’ he used to say, years later. ‘My grandfather and father were bakers and I worked in the bakery as a boy – I was used to heat.’

Next after Johnny, and within the year, his brother Willie was born. Then two sisters came along: Harriet and Alice, who were six and eight years younger than Johnny. Finally, baby Dan joined the family when Johnny was already 11 years old. There might have been more but when the next baby, Philip, died in his mother’s arms, Ellen knew she would need all her energies to keep her family alive.

Life was hungry and tough, but in Manhattan you could always feed on dreams and no little boy could walk along the quayside in the New York of the 1890s without being mesmerised by all he saw and heard. Sometimes, Johnny would walk past ships being docked, watch cargoes being unloaded and study the faces of the seamen as they swung down the gangplank. For a moment, he would be a sailor, voyaging out to take on the world. He would weave these men into his adventures, playing out the hero, drinking in their excitement.

Ambition was a fire inside him, and Michael and Ellen Hayes, both exhausted long before their time, took some comfort in realising that their eldest son shrugged aside this poverty and still burned with the unquenchable energy of the young. Exactly what he wanted to do they couldn’t be sure, but still they admired the way he was not scared of hard work. They smiled with fondness at the effort and the hours he would put in and at his happy-go-lucky self-confidence.

But that confidence and thirst for hard work were about to be tested to destruction. Michael and Ellen, old long before they had reached middle age and wrung threadbare by the effort of surviving in New York, both died within weeks of each other in 1902. There was no money for a tombstone.

At the age of sixteen, Johnny Hayes found himself head of the family with two brothers and two sisters to support, the youngest of them just five years old. The children were taken into a Catholic orphanage and Johnny did what he had to to support them all there. He took the toughest, most dangerous job he could find, but a job that paid well for your sweat. It was working underground, digging tunnels for the New York subway, and shovelling sand until you dropped. They called the labourers ‘sandhogs’ and the work of the sandhogs was tedious, not to mention perilous and claustrophobic.

Johnny, and sometimes his brother Willie, worked shoulder to shoulder, straining to earn as much in a day as other labourers might bring home in a week. They needed the money now they had a family to keep. Each morning, the two boys would marvel at the tangle of derricks and scaffolding. There would be gangs of 60 or more men gulping hot coffee. Following a roll call, they would walk single file to the mouth of the shaft. Most of the men wore nothing but their shirts and trousers with waterproof boots reaching above the knees.

Just entering the tunnel took a long time. Crews would go into airlocks, one at a time, after which the doors at each end were sealed. An air pipe would start hissing and the men’s ears popped as the air pressure climbed until it was the same as in the adjoining locks which took them underground. Then the workers were able to open the connecting door and crush into the next chamber, where the entire ordeal would start all over again. Once they got to the far end of the tunnel the men had to work quickly because they could only handle the pressure for a short while.

‘Pinch your noses, keep your mouth shut and blow!’ the foreman would yell. ‘It helps your ears.’ Sometimes eardrums would rupture and bleed, and the two Hayes boys soon learned the dangers of working too fast in these conditions.

‘You need to pace yourself,’ Johnny would say to his brother. ‘Don’t go so fast at the beginning.’ Above all, the job was wet, and the dampness seemed to seep into their very bones. Half-remembered warnings from his now-dead Irish mother niggled away at Hayes’ weariness. ‘Keep yourself dry, Johnny boy,’ he could still hear her saying, ‘the rheumatism is a terrible thing – it’s the ruining of the joints.’

When he wasn’t working, Hayes would catch up on his sleep and fool around with the other Irish lads, sharing stories of sports heroes, throwing a ball, swinging a bat and sometimes for fun taking part in an impromptu foot race.

When Johnny was just ten years old, he experienced the ballyhoo that surrounded the return of the Americans from the first Olympic Games in Athens. No boy could forget the excitement of the crowds and bands, the flag-waving and the cheering, as New York saluted their conquering heroes. And among those heroes was the very first winner in those 1896 Games, an Irish-American boy like Johnny himself and a fine all-round athlete called Jim Connolly.

Connolly had won the hop, step and jump, and a year later he went on to become a prolific writer on sport, an author of sea sagas and a newspaper man for the Boston Globe and the Boston Post. But the ten-year-old Johnny Hayes never forgot the sight of him draped in the Irish tricolour on his way through Manhattan. Connolly made a huge impression on Hayes and all the other Irish-American boys in New York.

Aggressively proud, not only of his Olympic victory but of his Irish roots and sporting heritage, Connolly had been raised in the predominantly Irish-Catholic neighbourhood of South Boston. ‘We were a hot-blooded fighting lot, but also clean living, sane and healthy,’ he wrote. ‘The children grew up rugged and just naturally had a taste for athletics. Among the boys I knew as a boy it was the exception to find one who could not run or jump or swim, or play a good game of ball.’

Local sporting heroes figured prominently in the young Jim Connolly’s life. Among them was John L. Sullivan, the ‘Boston Strongboy’ and a world heavyweight boxing champion from 1882 to 1892. Another was a neighbour by the name of Gallohue, who enjoyed fame as a circus acrobat, and it was to him that Connolly attributed his earliest interest in track and field athletics.

‘Our curious jumper of whom we were all very proud,’ he wrote, ‘was a true picture of an athlete six feet in height and weighing 190 lbs stripped.’ On one occasion, Gallohue came home dressed in a superb new suit, which Connolly estimated had cost at least $60 – ‘a lot of money for a suit of clothes then’. It turned out that the suit was a pay-off for a bet made by the circus manager and that to win it, Gallohue had to jump over a baby elephant.

‘It was the professional athletes who were our role models,’ said Connolly. ‘In those days the Scotch and Irish societies used to run great festivals in the summer and the big drawing cards were the professional athletics games. We had schools of professional running then, not one but many. Every shoe town, every other mill town, had its champion. Towns would go broke backing their man.’

In May 1896, Johnny Hayes had seen his hero Jim Connolly wave his way across New York through a double line of policemen with crowds from kerb to kerb. Red, blue and green ribbons were everywhere and skyrockets flared from drug stores, homes and bar rooms, while a band beat out ‘See the Conquering Hero Comes’. Hayes cut out a newspaper picture of the scene and kept it in his pocket until it fell to pieces.

In the years that followed, Connolly would hand out training advice to any young Irish-American who dreamed of emulating his deeds in track and field.

‘Practise easily, but regularly,’ he would say. ‘Over-training is worse than under-training. After exercise, take a cold, quick sponge bath and rough towel rubbing. Eat any plain food you like, drink as little liquid as you can during the day of a race outside of your usual allowance of tea or coffee. Do not run the day before a race. From four to five in the afternoon is the best time to exercise and about five times a week usually gives the best results.’ It was good advice and not wasted on boys like Hayes.

Connolly was convinced that his Irish lineage was in large part responsible for his sporting successes, but he was also proudly Catholic. ‘It is in the blood and training of our Catholic boys to be not merely American,’ he wrote, adding, ‘These Catholic youths, patriots and athletes out of all proportion to their numbers are mostly such because of good Catholic motherhood and a wholesome childhood.’ He thrived on hero worship and he got plenty of that; he was even the subject of Theodore Roosevelt’s admiration when, in 1908, the President of the United States said, ‘There’s a great all-round man, Jim Connolly, mentally and physically vigorous and straight as a whip. I would like my boys to grow up like Jim Connolly.’

Growing up like Jim Connolly, with his fierce pride in sport and Ireland, captivated the young Hayes. The job as a sandhog had toughened up Johnny and Willie a lot. They learned how to pace their young bodies over the long, exhausting hours spent underground. There, they learned it was fatal to start shovelling too fast and they learned to build up their stamina slowly, for you still had to be on your feet at the end of the day.

Their work did not leave them a lot of time for relaxing, but when the priests at the orphanage organised ball games and foot races, the two boys, toughened by their underground work, showed their strength. Hard physical work was making Hayes fitter by the week. When he had a few pennies in his pocket, Johnny still had energy to burn, and with his friends he would go dancing at the Manhattan Casino in Harlem. They would happily jog all the way home at two in the morning.

These boys could run and the priests noticed it. ‘Look at young Jack Hayes,’ they would say, ‘he could be a champion, a fine Irish boy like that. Get him out of shovelling sand all day and you’ll see him run like a racehorse.’

No one would question the pull that the Irish-Americans had in New York at the turn of the century. If an immigrant needed naturalisation papers, a Tammany Hall man was there to pull the right strings; if a poor Irish boy got himself arrested, a Tammany lawyer bailed him out. Whenever an old widow couldn’t pay the rent, Tammany money would come to the rescue. It was a simple enough deal – it was tit for tat. And all the Irish had to do to meet their end of the bargain was to vote the right way. With a word here and a word there, it was simple enough to get a promising young athlete onto a payroll, where the duties would be minimal or even non-existent.

Johnny Hayes, they decided, needed time to train, to rest, to race and to be coached. They had a word with the man who was president of the Irish-American Athletic Club, Patrick J. Conway. A close friend of the mayor, he joked about the Irish-American lad working every day in water up to his knees, saying how rheumatism might ruin a fine athletic career.

‘We’ll find him a dry job,’ declared Pat Conway, and before he knew it, the young Hayes was on the payroll of a New York store then called Bloomingdale Brothers. When he showed up for work, the store said Mr Conway had suggested that he work in the dry-goods department. For Johnny, anything had to be better than ruining his health as a sandhog, and while at Bloomingdale’s, his duties were variously described as a messenger, an odd job boy, an assistant in the caretaker’s office or even a shipping clerk.

But his real job was to collect his money. Later, when he had found success and fame as an athlete, the store collected on their investment, plastered the place with pictures of him and put out stories of how he had trained on a quarter-mile track on the roof. In fact, Hayes rarely got to work in Bloomingdales, much less train on the roof. His so-called job was one of convenience arranged for him by the Irish-Americans and Pat Conway. The truth was that from the moment Johnny stopped being a sandhog, he became a full-time athlete. He drew a steady salary, reported to be $20 per week, but instead of working he spent his time training for long-distance running in the parks and roads beyond Manhattan.

Already, John Joseph Hayes had stepped way beyond Baron de Coubertin’s romantic dream of strict amateurism; already he enjoyed unlimited hours to train and professional coaches to train with. But he was not the only one…

Even in faraway Britain, they hadn’t managed to kill off the professionals.