Читать книгу The Lives of Robert Ryan - J.R. Jones - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеone

Inferno

The day Robert Ryan turned nine, the entire nation celebrated. All weekend long had come word that the Armistice was about to be signed, bringing home a million American soldiers from the trenches of France. In Chicago, where the boy lived, whistles began to sound and guns to go off in the predawn darkness of Monday, November 11, 1918. Women ran from their homes with overcoats tossed over their nightgowns, beating on pots and pans. The elevated trains coming from the Loop tied down their whistles and went screaming through the neighborhoods, confirming that the nation was at peace. People who ventured downtown for work were sent home by their employers, and by noon the neighborhood parties were rolling.1 In Uptown, on the city’s North Side, young Bob ran around telling people this was his birthday and returned home with a few dollars in change. His parents, Tim and Mabel, made him give back most of the money, but even so this was a great day. Everyone had called this “the war to end war” — if that were true, then he would never have to die in a trench.

The Ryans had no need for their neighbors’ charity; they were respectable, middle-class people who had worked their way up. Bob’s great-grandparents, Lawrence and Ellen Fitzpatrick Ryan, had immigrated from County Tipperary, Ireland, in 1852 during the Great Famine and settled in Pittsburgh, where times were tough (their son John would later tell Bob about the “No Irish Need Apply” signs that greeted them on their arrival). The family moved to Chicago four years later and eventually retreated about thirty miles south to the heavily Irish Catholic river town of Lockport, Illinois, along the Illinois and Michigan Canal.

John and his older brother, Timothy E. Ryan, worked together as boat builders in the 1860s, then went their separate ways as John established his own business in town and Timothy (known as “T. E.”) returned to Chicago to try his hand at real estate speculation. John served as superintendent of the canal at one point and, with his wife, Johanna, raised a family of eight children. He liked his glass. “Although my grandfather drank a quart of whiskey a day for sixty-five years, he was never drunk or out of control,”2 Bob later recorded in a memoir for his children.

Up in Chicago, T. E. Ryan prospered, cofounding the real estate firm of Ryan and Walsh and building his family a mansion on Macalister Place on the Near West Side. He also established himself as a political brawler in the city’s well-oiled Democratic machine. Through the 1890s he won five terms as West Side assessor, and from 1902 to 1906 he served as Democratic committeeman for the Nineteenth Ward. T. E. was widely regarded as boss of the West Side, so popular and influential that, during the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, he was named grand marshal of the Irish Day parade. A portrait reproduced in an 1899 guidebook to state politics shows a handsome man with swept-back hair, a handlebar mustache, and a hungry glint in his eye. “One of the most popular men on the West Side,” the guidebook reported, “and a politician whose power is as strong as ever.”3 His success exerted an irresistible pull on John’s sons, and one by one they all drifted to Chicago.

Timothy Aloysius Ryan was the second of John’s children, born in 1875, and in the 1890s he headed north to board with his illustrious uncle and get into business in the city. Tim proved to be an eager political protégé: in 1899 he was appointed chief clerk in the city attorney’s office, and five years later he ran for the state board of equalization in the Eighth Congressional District, billing himself as “T. A.” Ryan. His uncle bankrolled all this, apparently seeing in his tall and handsome young nephew a rising political star. Tim got himself started in the construction business and ran an unsuccessful campaign for West Town assessor, his uncle’s former position. “Father’s duties have always been somewhat vague in everyone’s mind,” Bob wrote. “In his twenties he seems to have been occupied principally with fancy vests, horse racing, attending prizefights, and a great deal of social drinking. In short, a rather well-known and well-liked man about town.”4

By 1907, Chicago was home to five of John and Johanna’s sons. They were big men — one of Bob’s uncles stood six feet eight inches tall — with ambitions to match. Larry, Tim’s younger brother by eight years, had come north to clerk for T. E.’s real estate firm, and Tom, Joe, and John Jr. wanted to start their own construction firm so they might capitalize on their uncle’s political influence. But the brothers’ relationship with their uncle ruptured. According to Bob, Larry’s job “involved handling some funds and he was ultimately accused by his uncle of a minor embezzlement. Larry was about as liable to have done this as to burn down the Holy Name Cathedral. Father sided with his brother and left his uncle’s bed, board, and generous patronage for good.”5 From T. E.’s power base in the west, Tim and Larry relocated to the relatively unpopulated North Side, where they banded together with their siblings to turn the newly christened Ryan Company into a going concern.

Timothy Aloysius Ryan, the actor’s father. Informed once that a gubernatorial candidate had been accused of embezzling fifty thousand dollars, he remarked, “Any man who could only steal fifty thousand dollars in that job isn’t smart enough to be governor.” Robert Ryan Family

Tim was thirty-two the night Larry introduced him to Mabel Bushnell, a lovely twenty-four-year-old secretary at the Chicago Tribune. Raised in Escanaba, a port town on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, Mabel was descended from some of the first English families of New York, though her father was a cruel and alcoholic newspaper editor from Gladstone, Michigan, whose career ultimately had given way to a tougher life as a tramp printer operating out of Rhinelander, Wisconsin. Tim took Mabel out on the town, squiring her to restaurants and theaters, springing for hansom cabs. He wanted her badly, but she took a dim view of his boozing, not to mention his political ambitions. Tim agreed to swear off liquor and politics, and in 1908 they were married, in a ceremony conducted by both a priest and a protestant minister. They moved into the apartment on Kenmore, and Robert Bushnell Ryan arrived late the next year — November 11, 1909.

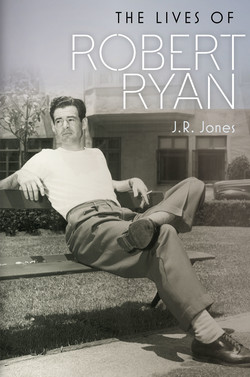

Robert Bushnell Ryan (circa 1912). “I was a completely nonaggressive youngster,” he later recalled. Robert Ryan Family

Two years later Mabel gave birth to a second child, John Bushnell, and the two boys slept in the same bed. “Very early in my life I remember the lamplighter,” Bob wrote, “a solitary youth who went around lighting the street lamps.”6 He and Jack enjoyed an idyllic life in Uptown, frolicking every summer on Foster Avenue Beach and running up and down the alley behind their house, an avenue for commercial activity. “Almost all heavy hauling was done by horse and wagon,” Bob remembered, and the alley “was full of various dobbins hauling ice, garbage, groceries, etc. In the hot summers the horses wore straw hats. The horses got to know the various stops and often would break in a new driver by showing him where to go.”7

The brothers’ friendship ended in June 1917 when Jack — “a rather solemn, gentle little fellow,” Bob wrote — died of lobar pneumonia, probably brought on by flu. He was not quite six years old. “I remember the terrible day that he died,”* Bob would write, “and the feeling of my mother and father that he might have been saved.”8 Devastated by the boy’s death, Tim and Mabel vacated their little apartment at 4822 Kenmore, blocks from Lake Michigan, and moved slightly northwest to a one-bedroom on Winona Street. “The neighborhood was somewhat less desirable,” Bob wrote. “But nothing mattered. We had to move and we did.”9 His parents, craving a portrait of little Jack, took a photograph they had of their sons on a dock and had Bob airbrushed away.

Now Bob slept alone, in a Murphy bed that folded out from the wall, like the one Charlie Chaplin had wrestled with in his two-reeler One a.m. He went to school alone, having transferred from Goudy Public School, which he remembered as mostly Jewish, to Swift Public School nearer his home. His parents were Victorian people, reserved even with their own child; and as the years passed, Bob learned to keep his own company, reading endlessly and roaming around the new neighborhood.

One unique attraction was the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company on Argyle, founded a decade earlier and now the city’s premiere movie studio. Chaplin had made films for Essanay in 1915, and Gloria Swanson and Wallace Beery had gotten their start there; Bob would remember seeing them all on the streets of Uptown. He and his school friends even spent their Saturday afternoons appearing as extras in the two-reel comedies of child star Mary McAllister, each earning the princely sum of $2.50 a day.

He was naturally quiet, even withdrawn, and his parents worried over his introverted nature. Mabel gave him a violin that once had belonged to her brother and every Friday marched Bob to the elevated train and downtown to Kimball Hall for a lesson. His teacher, a Scandinavian player for the Chicago Symphony, couldn’t do anything with him. Tim, knowing full well that a boy carrying a violin down the streets of Chicago would be a magnet for bullies, signed Bob up for boxing lessons at the Illinois Athletic Club, where a coach by the name of Johnny Behr taught him how to fight. Bob loved boxing: he was smart and quick in the ring, and he realized that if you didn’t worry about the punch it didn’t hurt as much. “Athletic prowess did a lot for my ego and my acceptance in school,” he later told an interviewer. “The ability to defend yourself lessens the chance you’ll ever have to use it.”10

Chicago could be an ugly place. Eight months after the Armistice was signed, Bob saw the city erupt again, this time in violence. Temperatures in the nineties had irritated tensions on the Near South Side between blacks confined to the Twenty-Fifth Street Beach and their white neighbors on the Twenty-Ninth Street Beach. On July 27, 1919, a black boy rafting near the shore at Twenty-Ninth Street was killed by a white man hurling rocks, and the incident touched off five days of murderous rioting. “As rumors of atrocities circulated throughout the city, members of both races craved vengeance,” wrote historian William M. Tuttle Jr. “White gunmen in automobiles sped through the black belt shooting indiscriminately as they passed, and black snipers fired back. Roaming mobs shot, beat, and stabbed to death their victims.”11

Thirty-eight people died, and more than five hundred were injured. An official report would blame much of the initial violence on Irish athletic clubs such as Ragen’s Colts and the Hamburg Club, but the rage had spread like an infection, creeping into the West and North Sides. (Just south of Uptown lay one of the North Side’s isolated pockets of blacks.) For a boy not yet ten, the riot must have been a frightening experience. Not only could war go on forever, it could happen right in your own backyard.

THE RYAN FAMILY’S FORTUNES began to turn in 1920 when Tim’s friend Ed Kelly was appointed chief engineer of the Chicago Sanitary District. Son of a policeman, Kelly had started out with the district at age eighteen, and though he had studied engineering at night school, he displayed more talent as a South Side politician, having founded and been elected president of the two-hundred-member Brighton Park Athletic Club. The Irish athletic clubs were mainly social, organizing team sports, but they were also politically oriented, and Kelly soon made a name for himself in the Cook County Democratic Party. By the time he became chief engineer, he had put in more than thirty years with the district. His spotty formal training was much noted in the press (one muckraking journalist accused him of farming out his technical work to consultants). Yet Kelly understood and had mastered the operating principle of Chicago politics: take care of your friends and they’ll take care of you.

Under Kelly, the Ryan Company won lucrative city jobs paving streets and building sewer tunnels. Tim, who supervised sewer construction, worked from 5:30 AM until 8 or 9 PM at night; he and his son barely saw each other except for weekends. With his winning manner and many connections, Tim was critical to the operation, though according to Bob, the man who really ran the company was his Uncle Tom, “a rather cold and shrewd businessman.”12 Flush with the company’s profits, Tim and Mabel decided to move again, this time to a bigger apartment, in the northerly Edgewater neighborhood, that was only a block from the lake. They bought their own automobile and furnished their new home well. During the summers Bob went to Camp Kentuck in Wisconsin, while his parents enjoyed golfing weekends in Crystal Lake, northwest of the city. Mabel might have succeeded in keeping Tim away from drink, but politics was another matter, and Kelly could always rely on T. A. Ryan as a Democratic Party committeeman for the Twenty-Fifth Ward.

Haunted by the memory of little Jack, Tim and Mabel would never have another child, choosing instead to spoil and smother Bob. “You cannot know the difficulties that attend an only child,” he would write years later, in a letter to his own children. “Two big grown-ups are beaming in on him all the time — even when he isn’t there. It is a feeling of being watched that lingers throughout life.”13 He hid in the darkness of the movies, spending countless afternoons at the Riveria Theater on Broadway or the smaller Bryn Mawr near the “L” stop. The charm and dash of Douglas Fairbanks were his greatest tonic, and he never missed a picture: The Mark of Zorro, The Three Musketeers, Robin Hood. Bob had seen how motion pictures were made and was fascinated by the results. Yet he could barely conceive of the movies as an occupation; his father and uncles considered the Ryan Company a legacy for their children.

After Bob graduated from Swift in 1923, his father pulled some strings to get him a summer job as a fireman on a freight locomotive, which satisfied the thirteen-year-old boy’s appetite for freedom and Tim’s desire that he learn the value of a dollar. Rumors of petting parties at the local public high school had persuaded Mabel that Bob needed a private education, and that fall his parents enrolled him at Loyola Academy, a Jesuit college prep school for young men that was located near the Loyola University campus to their north. The experience would shape him not only as a person but also as an artist.

Loyola was heavily Irish Catholic, the sons of an aspiring middle class, and the class of 1927 would produce an unusual number of Jesuit priests. Tim must have been pleased that his son would be schooled in the Catholic faith, though Mabel valued Loyola more for its academic reputation. The priests were known as stern taskmasters, and the curriculum was tough — along with the arts and sciences, the boys learned Latin, Greek, and Christian doctrine. Later in life, when Bob Ryan’s interests had turned to education, he would take a more skeptical view of Jesuit schooling. “The fathers were well-seasoned men who had a good deal of authority that they seldom used,” he remembered. “Huge areas of a fruitful life were almost ignored. Jesuit education was books and drill and writing and some discussion.”14

At the new school Bob began to distinguish himself in athletics, especially after a growth spurt propelled him to a height of six-foot-three, only an inch shorter than his father. He played football all four years and competed in track and field. Formidably big and agile on the gridiron, he was an All-City tackle his senior year. In school he struggled with Latin and especially chemistry but excelled in English, joining the literary society and working on the school magazine, The Prep. He read voraciously. “Truly, I may say that a man’s best friends are his books,” he wrote in the magazine his junior year. “Your companions may desert you, but your books will remain with you always and will never cease to be that source of enjoyment that they were when you first received them.”15

Ryan with his parents, Mabel and Tim. “You cannot know the difficulties that attend an only child,” he later wrote. “It is a feeling of being watched that lingers throughout life.” Robert Ryan Family

The book that changed his life was Hamlet, which he spent an entire semester studying under the instruction of his beloved English teacher, Father Joseph P. Conroy. The priest led the boys through the Elizabethan verse into the dark heart of the play, the young prince charged by the ghost of his dead father to avenge the treachery of his uncle, Claudius, and the unfaithfulness of his mother, Gertrude. Hamlet was full of moral conundrums, the hero torn between his conscience and his thirst for revenge. Bob was captivated: such rich language, such profound thoughts, such high drama. By the end of the semester he could recite practically the entire text. He fell in love with theater, reading Shakespeare, Chekhov, Shaw, and O’Neill, a writer who spoke to his own Irish melancholy. Their work awakened in him a hunger for self-expression, and he wondered if, instead of following his father into construction, he might become a playwright himself.

The money kept rolling in at the Ryan Company, and before long the family bought a Cadillac, then a Pierce-Arrow with a chauffeur to drive Tim to work. Bob got his own Ford and tooled around in bell-bottom suits and a fur coat. Tim became a patron of the Chicago Opera Association; he took Mabel to New York City to see all the shows. (Bob shared their love of musical theater; among his favorite performers were Fanny Brice and the great Irish-American showman George M. Cohan.) Tim Ryan, Bob wrote in a letter to his own children, “was always generous and kind to me — in a day when father-son relationships were not thought of as they are now.” His father was “a big man (6′ 4″ — 250 lbs.) with a radiant personality and strong sense of humor, and was idolized by many people. His other side was only displayed at home and was very hard to take.”

Bob wouldn’t elaborate on this statement, but he would note his father’s ambivalence toward the construction business, which hardly inspired one to join him. “Dad, I think, would have been content to have enough money to live well, eat well, play bridge, and tell stories to his rather small circle of friends.”16 Friction between father and son began to build as Bob’s graduation from Loyola drew near. Tim had mapped out his son’s future: he would stay at home, earn a professional degree at Loyola or DePaul or the University of Chicago, and find a good living for himself as the next generation of the Ryan Company. Bob insisted on going east to school and won admission to Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire.

That summer he accepted an invitation from his former camp counselor, a wealthy Yale graduate named Frank Scully, to work at a dude ranch Scully was trying to start on some land his family owned in Missoula, Montana. Bob took the train out West, spent the summer sharpening his horseman skills, and even found time for a first romance with a girl named Thora Maloney. He would remember his awe at seeing “plains that never ended — where one seemed to be becalmed in a purple ocean. As we got into the foothills of the Rockies and finally saw some of the high peaks I was aware of a lift of spirit that I shall never forget. It was strange to be so far from home and yet to feel as if I was coming home.”17

Back in Chicago he gathered his belongings for school and at long last left his parents behind. His father was pained to see him leave. “He didn’t get the point — packing off 1,300 miles to the state of New Hampshire when there were five colleges to be had within an hour’s drive,” Bob would write. “Mother must have sensed that I should go — though I hope she didn’t know how much I wanted to go.”18

At Dartmouth he pledged Psi Upsilon (one of his fraternity brothers was Nelson Rockefeller) and went out for track and football. But his real claim to fame was boxing: in his freshman year he won the college its first heavyweight title. His grades were unspectacular; he maintained a C average, studying Greek, French, English, physics, evolution, philosophy, and citizenship. The following summer he returned to Scully’s ranch, pursuing romance with another girl, Thula Clifton, and in the fall he played football again, though his career ended ignominiously after he broke his knee in a game against Columbia University. The injury threw his schoolwork into disarray, and in December 1928 he withdrew from all his classes without receiving any grades, standard procedure for someone flunking out.

For the next eight months Bob returned home to his parents, who had moved to a new apartment on Lake Shore Drive. Tim insisted that Bob work, so he got a job as a salesman, first for a steel company and then for a cemetery. “I’m offering a permanent product,” he would tell his customers.19 That fall he reenrolled at Dartmouth, starting over as a sophomore, and though he would continue to box, he had resolved to get serious about his studies.

A month after he returned, the stock market crashed. October 23 brought the first wave of sell-offs, then on October 29 — “Black Thursday” — the bottom dropped out. Crowds gathered outside the Chicago Stock Exchange, where a record one million shares changed hands in a single day. The Ryan Company was privately held and, at that point, worth at least $4 million. But each of the brothers was personally invested in the market, and they were all wiped out. All they had left was the promise of more construction work.

Even that seemed precarious: earlier that year Assistant State’s Attorney John E. Northrup had returned indictments against Ed Kelly and a dozen other men at the sanitary district, charging that they had defrauded taxpayers of $5 million over the past eight years and done a healthy business in bribes and kickbacks from contractors. “A well-greased palm was essential to doing business with the department,” wrote Kelly’s biographer, Roger Biles. “Some trustees received gifts of twenty-five cases of liquor a month from favored contractors.” Others “admitted financing lengthy European vacations with illegally solicited contributions.”20 Kelly would later concede to the IRS that from 1919 to 1929 his income was $724,368, though his salary for that period totaled only $151,000.

More than seven hundred people were called to testify, many of them against their will. Witnesses exposed gaping discrepancies between the district’s stated expenditures and what contractors were actually paid: the payroll was said to be padded by as much as 75 percent. The trial revealed that bids were submitted in plain envelopes that were later opened and altered so that favored firms could be awarded lucrative contracts. Elmer Lynn Williams, publisher of the muckraking newsletter Lightnin’, alleged that the district’s central auto service had provided high-ranking officials with “young women procured for these tired business men by an older woman who was on the pay roll. The taxpayers were charged for vanity cases, whiskey and the time of the ‘entertainers.’”21

None of the Ryan brothers was ever implicated, but the scandal soiled the reputations of everyone doing business with the district. Kelly escaped conviction only when the judge in the case, who was pals with a local Democratic boss, quashed the indictments and Northrup, forced to reassemble his case before the statute of limitations ran out, dropped the chief engineer as a defendant. Years of hardball Chicago politics had turned Tim Ryan into a cynic when it came to graft; informed once that a gubernatorial candidate had been accused of embezzling fifty thousand dollars, he remarked, “Any man who could only steal fifty thousand dollars in that job isn’t smart enough to be governor.”22

EIGHTEEN MONTHS AFTER THE CRASH, in April 1931, Tim suffered another devastating blow. One of his sewer projects for the city, southwest of the Loop in the Pilsen neighborhood, was engulfed in a horrific fire that burned for nearly twenty-four hours and claimed at least a dozen lives. Bob would come to view the disaster as a key factor in his father’s death.

The Ryan Company had contracted to build the Twenty-Second Street section of a huge, $2.1 million concrete intercepting sewer that would travel southwest to the sanitary drainage and ship canal. During construction each block-long section of the ovoid, seventeen-foot tunnel was sealed off to maintain air pressure and prevent collapse; the only exit was a short, perpendicular work tunnel that led to an elevator shaft. The cause of the fire was never officially determined, but according to several newspaper reports — including one that cited Tim Ryan as its source — a cement worker had dropped a candle (used to detect air leaks) into a pile of sawdust. Timber and sawdust were major components in tunnel construction: wooden forms used to mold the concrete were braced against the earthen walls and anchored in place with sawdust packs. The fire began to spread underneath the concrete, pumping black smoke into the tunnel.

At street level a foreman noticed a ribbon of smoke drifting up from the elevator shaft and, fearing an electrical fire, sent three electricians down to check the wiring; they found nothing wrong. Tim learned of the fire around 6 PM, and the first workmen to flee the tunnel reported a smell of burning insulation, which led him and his crew to believe the cause was indeed electrical. Morris Cahill, the construction superintendent, warned them that if the fire reached the east end of the tunnel and destroyed the hoses maintaining the air pressure belowground, the entire tunnel section would collapse.

According to the Daily News, loyal employees begged Ryan to let them extinguish the fire: “We’ll be okay, boss. Let us go, please. It’ll mean your contract if we don’t.”23 Without waiting for Ryan’s permission, an assistant foreman led a party of men down into the tunnel; Cahill made three trips down but each time was overcome by smoke. With no word from the men below, Ryan summoned the fire department around 7 PM.

“My men are in there!” Tim exclaimed as the first engine company arrived on the scene. “What are we going to do?”24 Confusion over the fire’s cause and ignorance of its severity may have been as deadly as the blaze itself: the first two rescue parties descended into the tunnel without the benefit of gas masks. The operation went on for hours, slowed by the thick smoke and the difficulty of getting at the burning material. When the fire broke out, panicked workmen had retreated into the metal chambers at either end of the tunnel section, which were sealed by an air lock and offered fresh air pumped in from street level thirty-five feet above. As the fire raged out of control, it pushed firefighters back into the chambers as well, and the trapped men waited through the night, praying and trying to lie still.

By midnight the construction site looked like the scene of a mining disaster. A light wagon trained its searchlight on the mouth of the elevator shaft, and thousands of spectators, some of them distraught family members of Ryan employees, were being held back by a police cordon. Hospital squads had arrived on the scene and set up shop in a neighboring lumberyard. More than two dozen firefighters had already been taken to Saint Anthony Hospital, and the fire department had by now dispatched a full quarter of its forces to the site.

Firefighters attacked the superstructure over the elevator shaft and eventually managed to tear the roof off in an effort to provide more ventilation. Mining equipment arrived, and mine workers from around the city converged on the site to volunteer their services. After the utility companies shut off the electricity and the Twenty-Second Street gas main (located a perilous ten feet from the tunnel), crews of men with picks, shovels, and pneumatic drills started three new ventilation holes in the concrete — one above each air chamber and another at the center of the tunnel.

No plan was too far-fetched: a professional diver who lived on the North Side was recruited to venture into the tunnel in his wet suit, but after only a few minutes he signaled for help and was brought back up — the rubber was melting. A description in the Chicago Evening Post sounds like a scene from Dante: “Terrific heat developed in the cramped quarters underground. Blazing timbers fell.… Water, poured above the tunnel in a vain effort to cool it and dissipate some of the fumes, eddied, four feet deep in spots, and made it impossible to see even inches ahead in the thick white mist.”25 Sometime during the night, the air supply inside the east air chamber failed, and the laborers and firefighters trapped inside decided to make a break for it, but most them died of smoke inhalation before they could reach the elevator shaft.

Outside, the rescue effort was beginning to reach across state lines. Henry Sonnenschein, secretary to Mayor Anton Cermak, brought word from his boss, who was vacationing in Miami Beach, that the city would spare no ex pense in addressing the crisis, which threatened to become a citywide calamity if the fire breached the east and west walls of the tunnel into the remainder of the sewer line. By 3 AM a rescue squad from the federal mining bureau had roared out of Vincennes, Indiana, for Chicago, escorted by state police. A squad from the state mining bureau in Springfield boarded a special train with right-of-way cleared to the site of the disaster. But the critical arrival, just after dawn on Tuesday, was an experimental smoke-ejector truck designed by an inventor in Kenosha, Wisconsin. A modified fire truck, the smoke ejector was essentially a gigantic vacuum cleaner on wheels, and its long, flexible fourteen-inch tubes were extended down the mine shaft to suck the smoke out of the tunnel.

The crowd roared later that morning when sixteen men trapped in the metal chamber and already given up for dead began emerging from the elevator shaft. Early that afternoon rescuers recovered the last dead man from the tunnel: Captain James O’Neill, one of the first firefighters on the scene, who had been trapped in the east chamber and was trampled near the air lock by the stampeding workmen as they tried to escape. The final death toll was four firemen and seven laborers, plus a policeman who had been run over by an ambulance. Nearly fifty other people had been injured, some seriously. Later that afternoon, the young widow of Edward Pratt, a firefighter whose body had been recovered overnight, broke past the police cordon and tried to hurl herself down the elevator shaft.

By that time Tim had been summoned to the county morgue, where Dr. Herman N. Bundesen, the Cook County coroner, was convening an inquest to determine how the fire had started and how the eleven men had died. Bundesen had a long history with Ed Kelly, having worked for the sanitary district during the Whoopee Era; according to journalist Elmer Lynn Williams, he had proved himself “one of the pliable tools of the machine.”26 Kelly, still holding firm in his capacity as chief sanitary engineer, served as technical advisor to the inquest.

Called to testify, Tim Ryan wept as he recalled the first crews of firefighters going after his trapped workmen: “I saw men going down into that reeking tunnel without gas masks — without masks. I never saw such courage displayed in my life.”27 Neither he nor his construction superintendent could state with certainty what caused the fire, and the news accounts of a workman igniting a pile of sawdust never were introduced.

When the inquest reconvened a week later in a courtroom at City Hall, the panel ruled that all eleven men had died of smoke inhalation but declared the cause of the fire unknown. “Unofficially,” reported the Chicago American, “the jury members expressed the view that no human agency was at fault in the fire and tragedy that followed; that all precautionary measures were maintained by the contractors to safeguard life.”28 The city was indemnified against liability for the workmen’s deaths; the Ryan Company would pay any settlements to the families through its compensation insurance. A pall hung over the firm, exacerbated by the Kelly corruption charges still crawling through the court system.

IN THE QUIET SECLUSION OF HANOVER, Bob must have been even more determined not to join the Ryan Company. His grades had improved substantially; he was earning mostly B’s now and the occasional A in English or comparative literature. He had reclaimed his record as an intercollegiate boxing champion and — encouraged by his coach, Eddie Shevlin — even entertained thoughts of becoming a professional fighter. But his father talked him out of it: most boxers, he pointed out to Bob, were washed up at thirty. Bob was tired of athletics anyway. Having defended the heavyweight title in his sophomore and junior years, he retired from the ring to devote himself to his degree in dramatic literature.*

His best friends were still his books. The 1920s had brought a great revival of interest in Herman Melville, and Bob was floored by Moby-Dick. Something in Ahab’s lonely obsession spoke to him; his daughter, Lisa, would remember him ritually reading the book every year.29 He adored Joyce, especially Ulysses, but his tastes also ran to more popular fare; at Dartmouth he sold a professor and several of his classmates on Joseph Moncure March’s 1928 narrative poem The Set-Up, about a black boxer who runs afoul of gangsters.30

As an admired upperclassman, Bob drove around campus in a Buick roadster, took up smoking a pipe, and made bathtub gin. Prohibition had been in effect since 1919, and overturning it had become a touchstone for Democrats. In a nod to his father’s electoral ambitions, he ran for class marshal on the slogan “Rum, Rebellion, and Ryan.” His flyers declared him in favor of “free beer, free love, and free wheeling.” But that summer would bring him closer to genuine lawlessness than he could stomach. “I answered an ad,” he later recalled. “An oil man wanted a chauffeur. He took one look at me and said I was it. I ferried him around for two weeks before I discovered he was a bootlegger and that he was taking me along as a bodyguard.”31 Bob soon quit the job.

As an undergraduate at Dartmouth College, Ryan became an intercollegiate boxing champ and ran for class marshal on the slogan “Rum, Rebellion, and Ryan.” Robert Ryan Family

Without the athletics, his academic performance improved; he made Phi Beta Kappa in his junior and senior years, wrote an essay on Shakespeare that was anthologized in a collection of undergraduate writing, and won a hundred-dollar prize for his experimental one-act play The Visitor, whose title character was the grim reaper and whose one and only performance took place in the college’s Robinson Hall. Now twenty-two, Bob had hung onto his blissful ignorance for as long as possible, but he began to understand that he would be graduating into harder times than any he had ever known. The Ryans’ life of luxury had evaporated as the country spiraled into depression. Tim wanted Bob to come home and help with the business, but Bob resisted. He would do anything but seal himself up inside an office.

After graduating in June 1932, Bob took what little money he had and moved to Greenwich Village with two fraternity brothers, intending to find a job as a newspaper reporter and work on his playwriting. A third of the country was out of work, and along the streets of New York people queued at breadlines and soup kitchens. Bob couldn’t figure out what he wanted to do with his life; he only knew he couldn’t go into business. He fought a professional bout under an assumed name to raise some cash, but otherwise the boxing went nowhere. A girlfriend got him gigs modeling for true-confession magazines and department store ads — he later claimed to be the first man in America to model French jockey shorts — but his pals gave him so much grief over this that he quit. For a while he worked as a sandhog, pushing rock barges through tunnels under the Hudson River.

In this economic climate the pampered young man oscillated between realism and sheer fantasy. Some pals from Psi Upsilon persuaded him to come in with them on a gold mine in Libby, Montana, and Bob moved out West to prospect with a friend. The living was rough; they had to break ice on a stream for bathing water. After four months they had managed to extract about eight dollars’ worth of gold. When Bob heard about a cowpuncher job in Missoula paying that much every week, he gave up on the mine, and eventually he returned to New York City, wearing a long beard and hitting up his classmates for money to get back on his feet.

Magazine profiles would offer differing accounts of how Bob managed to wind up a sailor aboard The City of New York, a diesel freighter making runs to South Africa, in 1933. According to one, he was strolling along the Brooklyn waterfront one day, visiting a friend, and when he saw the ship loading on the wharf, he impulsively asked for a job.32 According to another, he “accepted drinks one night from a jovial tramp steamer captain” and “woke next morning bound for Lourenzo Marques, Portuguese East Africa.”33 In any event, Bob shipped out as an engine room wiper, cleaning up oil that leaked from the cylinders and various pumps, oiling the pumps, and fetching coffee. Owned by the private Farrell Lines, The City of New York headed down the East Coast to New Orleans and then across the Atlantic, carrying manufactured goods. It probably docked in Cape Town, East London, and Durban, and it returned to New York two or three months later with shipments of raw asbestos or chrome.34

Bob might have been surrendering to his love of Melville and Eugene O’Neill, who had written of the seafaring life in Anna Christie and The Hairy Ape. He spent more than two years at sea, collecting stories of hardship and adventure. The equatorial heat was unbearable; once he had to intervene when a delirious female passenger tried to push her baby through a porthole. Another time, after the ship’s store of food spoiled, he subsisted for days on lime juice.

Whenever Bob heard from his parents, the news was grim. In December 1934 his Uncle Tom died, leaving the presidency of the Ryan Company to Tim. Soon after that both Joe Ryan and John Ryan died. The pressure of the construction industry was crushing them out like the cigarettes Bob now smoked daily. In January 1936, not long after returning home from a run, he received a phone call from his mother: his father had been hit by a car, and Bob was to return to Chicago at once to look after him and help out with a subway tunnel project. Bob made an inglorious return to Chicago as a common sandhog, pushing rock barges beneath the streets of the city by day and struggling to understand the business by night.

Tim’s accident had exacerbated a heart condition, and on April 27, 1936, he died of a coronary occlusion at Passavant Memorial Hospital. He was sixty. Writing to his children, Bob would quickly recount the stock market crash and the tunnel disaster, adding, “I am sure that both of these events caused my father’s early death.”35 Tim was laid to rest in Calvary Cemetery in the north suburb of Evanston, beside his little son Jack.

Bob knew he had to look after his mother and made a game effort to help his uncle Larry, now president of the Ryan Company and the last surviving brother at the firm. But he wanted out of the tunnels: one time, as he was breaking up rocks with a sledgehammer, he turned over a rock to find an abandoned dynamite charge. Another time he worked forty-eight hours straight when a power plant failure imperiled the air pressure in a tunnel. Eventually, he quit the company, drifting from one job to the next. One oft-repeated story had him working as a collector for a loan shark on the blighted West Side and, moved by the poverty he saw, coming back to return one family’s money. He was working as a gang boss on a WPA road paving crew for thirty dollars a week when his uncle Larry Ryan died in December 1937, only fifty-five years old. The Ryan Company would endure into the 1940s, but there was nothing left of the brothers now except their name.

Frustrated with her son’s career drift, Mabel finally called on Tim’s old friend Ed Kelly, who had not only survived the sanitary district scandal but ascended through a city council vote to become mayor of Chicago. After Anton Cermak was fatally wounded during an assassination attempt on President-elect Roosevelt in February 1933, Kelly had been pushed through the council by his old friend Patrick Nash, the Twenty-Eighth Ward alderman, and they controlled a formidable vote-getting operation that gave them enormous power over the city. Bob would remember Big Ed Kelly as an avatar of ward politics and no dreamer. One night in 1928, when Bob was home from college, he had been sitting in his parents’ living room when Kelly came calling for Tim, having just met Al Smith, the progressive New York governor and Democratic nominee for president. “He’s talking about things like welfare and human rights and all that shit,” Kelly complained.36

As mayor, Kelly had relaxed enforcement of gambling laws; according to the Chicago Crime Commission, the administration pocketed $20 million from organized crime one year to ignore illegal operations. At the same time Kelly had forged an alliance with Roosevelt and brought much-needed New Deal funding to the city. He went out on a limb politically with his vocal advocacy of open housing and school integration. To some extent this was pure politics: his success at drawing blacks away from the Republican Party contributed to his success at the polls. But Kelly acted too, appointing blacks to more influential posts, working to integrate the police department, and, at one point, shutting down a local screening of D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation. “The time is not far away,” he told one audience, “when we shall forget the color of a man’s skin and see him only in the light of intelligence in his mind and soul.”37

Now Big Ed would come through for the Ryans one more time, with a white-collar patronage job for Tim’s aimless son. Bob joined the Department of Education as an assistant vice superintendent, though his job consisted of little more than filling requisitions for school supplies. Under the leadership of James B. McCahey, a coal company executive and crony of the mayor’s, the board had developed a reputation to rival the sanitary district’s; local muck-raker Elmer Lynn Williams called it “the most corrupt Board of Education that ever cursed the Chicago schools.”38 Down in his little basement office, Ryan recalled, he “had little to do except combat hangovers,”39 so he spent a good deal of time writing, an infraction ignored by the other patronage hires. The boredom drove him mad — this was everything he’d struggled to avoid in his vagabonding days. He was pushing thirty, his father was dead, and he still hadn’t decided what to do with his life.

The answer came to him one afternoon when he ran into a friend and she talked him into taking a role in a local theater production. Despite his passion for theater, Bob could be painfully inhibited; he still winced at the memory of delivering a speech in grade school and hearing laughter ripple through the audience when his voice cracked. But he took the role, and something happened. “I never even thought of acting until I was twenty-eight,” he later recalled. “The first minute I got on the stage, I thought, ‘Bing! This is it.’”40

Electrified by the experience, Bob signed up for acting classes with Edward Boyle, a stock company actor who charged five dollars a week. “What an audience most likes to feel in an actor is decision,” Boyle would tell him. “Always keep saying to yourself, ‘Decision, decision, decision.’”41 After Bob’s mother informed him that the Stickney School, whose upper classes were college preparatory instruction for girls, would have to cancel its senior class play because the drama coach had taken ill, Bob managed to convince the principal that he was an experienced stage director and took over the production. The play was J. M. Barrie’s comic fantasy Dear Brutus, and the performance, on May 6, 1938, went off reasonably well. “With kindest regards for the first person who ever wanted my autograph,” Bob would write on a program for a friend.42

Bob silently hatched a plan that would get him out of Chicago for good: over the next couple of years, he would save a few thousand dollars, move to Los Angeles, and enroll in the acting school at the Pasadena Playhouse. In another era he might have set his sights on New York, but Bob was still smitten with the movies. “The very mention of them excites the imagination and stirs the blood,” he’d written in a high school essay. “We may walk out of our own world into another.”43 By now his focus had shifted from Douglas Fairbanks to the new generation of talking actors: Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy, and James Cagney, the latter of whom had become a star playing a Chicago gangster in The Public Enemy.

His ticket out of town arrived in summer 1938. Years later a couple of news stories about Ryan would refer to an inheritance, but the story most frequently told had him unexpectedly striking it rich on a friend’s oil well near Niles, Michigan, his three hundred dollars’ worth of stock paying a sudden dividend of two thousand dollars. His mother was dumbfounded when he informed her of his plan. “You can’t earn a living that way,” she insisted. “This little acting group you play with is nice, as a hobby. But I know you. You can’t act.”44 Act he would, and before long he had kissed his mother good-bye and boarded a westbound train from Union Station. Surely his father would have disapproved. “How sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is / To have a thankless child!”45 But then, if his father hadn’t struck out on his own as a young man, he would have spent his life caulking boats in Lockport, Illinois. Whatever sort of life Bob found for himself in Los Angeles, at the very least it would be his own.

*His death predated by only a few months the first recorded cases of the Spanish influenza, which would kill at least half a million people in the United States alone.

*Countless news stories would misreport that Ryan retired from collegiate boxing undefeated; in fact, Dartmouth yearbooks indicate he lost to his opponent at Western Maryland College on a close decision in the 1930 season and fought his opponent at University of New Hampshire to a draw in the 1931 season.