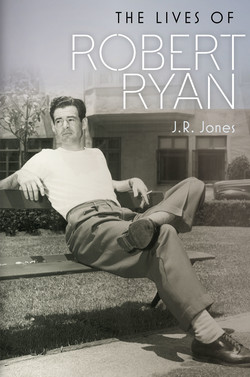

Читать книгу The Lives of Robert Ryan - J.R. Jones - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеfive

We Will Succeed, You Will Not

Jessica Ryan hated guns: she had no intention of letting her lovely Tim play with toy guns, learning to fantasize about combat and killing. Robert, a capable marksman in the Marines, didn’t feel that strongly, but he had no fondness for firearms either. “He went hunting once with his father and shot something,” his son Cheyney remembered. “He said he’d never do it again.”1

Regardless, the RKO publicists liked nothing better than to send Ryan on a hunting expedition. The previous November he had driven up to Oregon with actor Lex Barker to be photographed hunting geese, and that spring Jessica swallowed her pride and accompanied him on a jaunt out to the desert with a photographer for Photoplay and actress Jane Greer, who had just starred in Out of the Past for RKO. Jessica posed at the wheel of a jeep and stood by as Robert held up a dead jackrabbit for Greer’s inspection; the resulting story claimed that she and Greer each had bagged a rabbit as well.2 This was followed by another trip to a ranch in the San Fernando Valley to hunt pheasants for a four-page pictorial in Screen Guide; one photo showed the couple heading out from their car, Jessica scowling as she carries a rifle at her waist, the barrel pointed to her side.3

After Crossfire, Ryan strapped on his six-guns again for Return of the Bad Men, another B western with Randolph Scott and “Gabby” Hayes. He couldn’t wait to finish with this tired oater and move on to Berlin Express, an espionage thriller scheduled to begin shooting overseas in July. Dore Schary had been mightily impressed by the documentary authenticity of Roberto Rossellini’s Italian postwar drama Open City (1945), and he wanted Berlin Express to be the first drama filmed inside Germany since the fall of the Third Reich. (Director Billy Wilder would be arriving at the same time to shoot A Foreign Affair for Paramount.) Berlin Express centered on an international group of passengers riding a US military train from Paris to Berlin, and like Crossfire, it would mix genre entertainment with liberal politics, stressing the imperative of world peace.

Ryan would be gone for more than two months, flying from New York to London and then traveling with cast and crew to Paris, Frankfurt, and Berlin. He was excited about the picture and eager to get a firsthand look at the ravages of war. General George Marshall had just delivered a commencement address at Harvard in which he stressed the danger of allowing the European economy to deteriorate any further; he called for a massive economic aid plan to rehabilitate the victors and the vanquished alike. Berlin Express would carry Ryan right into the heart of this debate. He finished Return of the Bad Men in mid-July 1947, and yet another photographer arrived, this time at the house in Silverlake, to shoot him packing his bags and bidding Jessica and Tim farewell on his way to the LA airport.4 Jessica was afraid of airplanes and begged him to take a train east, but Ryan never passed up a chance to fly.

The producer, thirty-seven-year-old Bert Granet, was shouldering quite an operation. Military permits were required at each point of travel through occupied Germany, which meant that twenty-seven cast and crew members had to be screened by the FBI* and then cleared by the army and State Department.5 Cinematic resources in Europe were so scarce that nearly all camera and lighting equipment had to be brought over, along with one hundred thousand feet of film that required cool, safe storage in nations where any kind of storage space was prized. Because local film laboratories were so dodgy, all footage had to be shipped back to the United States for processing, so none of the completed scenes could be viewed until the expedition returned to Hollywood.6 Lodging and automobiles were in short supply (there was only one camera truck available in all of Paris); even simple items such as nails, lumber, and rope had to be bought on the black market.

A native Parisian, director Jacques Tourneur had come to Hollywood in the 1930s and distinguished himself at RKO with subtle, low-budget chillers such as Cat People (1942) and I Walked with a Zombie (1943). He had just completed his masterpiece, the wistful film noir Out of the Past. Unfortunately, Berlin Express didn’t have much of a script; inspired by a Life magazine story, it would be a rather awkward marriage of journalism and Hitchcock-style suspense, its harsh scenes of a ravaged Germany punctuating an increasingly far-fetched tale in which a German diplomat critical to the reunification effort is kidnapped by right-wing terrorists. The four heroes pulling together to foil this plot were obvious stand-ins for the occupying powers: Ryan is an American agricultural expert, Roman Toporow a Russian military officer, Robert Coote a British veteran of Dunkirk, and actress Merle Oberon the French secretary of the kidnapped politician.

Decades later Granet left behind in his papers an account of the personal chaos inspired by Oberon during the trip. The delicate British beauty had outmaneuvered him already by getting Schary to name her husband, Lucien Ballard, as cinematographer; the couple would be rooming together. The company was lodged at the Hôtel George V, just off the Champs-Élysées, but Oberon, in a standard movie-star power play, insisted that she and Ballard stay at the palatial Hôtel Ritz on the Place Vendôme. Ballard, an Oklahoman of part-Cherokee descent, was tall, athletic, cultured, and handsome; he had won Oberon’s heart by inventing a small spotlight that attached to the camera and helped minimize her facial scars from a 1937 car accident.*

“By the time we settled in Paris, Merle had developed a deep passion for Robert Ryan,” wrote Granet. “He was tough looking but at heart he was a happily married pussycat. He was not even fair game for someone of Merle’s sexual talents. She would tease him then cool it.”7 Born in Bombay to a Welsh father and an Indian mother, Oberon had spent her adult life concealing the mixed parentage that would have ended her career as an actress in Britain and the United States. For six years she had been married to the great British producer Alexander Korda, who cast her opposite Laurence Olivier in Wuthering Heights (1939), but in 1945 she had left Korda for Ballard. She obsessed over her beauty and exulted in her status, spoiling herself with clothing and gems. Oberon was high-strung and wildly romantic — among her previous lovers were Leslie Howard, David Niven, George Brent, and the heroic RAF pilot Richard Hillary.

During the company’s stay in Paris, wrote Granet, Oberon urged him and his wife, Charlotte, to throw a dinner party in their suite and invite Ryan. That evening she arrived hours late, dressed to the nines in a black evening gown and accompanied by a dapper Englishman; later she confessed to Charlotte that she was trying to make Ryan jealous. “By the time we were shooting in Frankfurt, she had successfully bedded Ryan,” Granet reported. “Since Lucien … was constantly on location, all he could do was develop suspicions. Merle successfully made him believe that it was Charles Korvin who was making a pass at her.”8

Ryan with Merle Oberon in Berlin Express (1948). Their affair unfolded amid the chaos and deprivation of postwar France and Germany. Film Noir Foundation

Korvin, a Hungarian actor playing one of the villains, had already shot two pictures with Oberon, and the two despised each other. More than thirty years later, after her death, Korvin told celebrity biographers Charles Higham and Roy Moseley that Oberon deserted Ballard on more than one occasion to spend the night with Ryan, first on the cross-country train from Paris and then in Frankfurt (where the crew lodged at hotels in the center of town and the cast was billeted at a castle in Bad Nauheim, thirty-five kilometers north of the city). “I know that she slept with Ryan both in Hollywood and in Europe and I thought it unfair and cruel of her,” Korvin remembered. “I objected to the affair and so did everyone else on the picture.”9

Political argument only added to the tension. When Ryan asked his fellow cast members how they felt about General Marshall’s vision for postwar Europe, the idea of economic aid for Germany got a cool reception. Coote and Oberon had endured the London blitz. Korvin and Paul Lukas, both Hungarian, had been personally touched by the Holocaust, and Toporow, who was Polish, loathed the Germans and the Russians alike. “How can you let 80 million people starve?” Ryan would ask.10 Invariably they dismissed him as naïve or softhearted; mass starvation, said one, would be no less than the German people deserved.

Their resolve began to melt away as they got a look at Frankfurt: entire neighborhoods reduced to rubble, middle-class people reduced to beggars. More than fifty-five hundred had been killed in the bombardment, and the medieval city center, the Römer, had been completely destroyed. In Berlin Express, Ryan and Oberon venture into the neighborhood and discover a maze of shoulder-high rubble, like a bizarre sculpture garden. Another scene shows Ryan staring grimly out a bus window as people walk the streets with suitcases full of belongings for sale; in the train station he tosses away a cigarette and two shabby men race like pigeons to scoop it up. The children they encountered on location were “emaciated, shocked and sick,” Ryan later wrote, with “old faces and rickety bodies.”11 By the end of the first week, he remembered, no one talked anymore about the justice of letting people starve.

From Frankfurt the company flew to Berlin, where principal photography began on Saturday, August 2. This time the company stayed in Zehlendorf, about fifteen miles from downtown, near the US occupation forces headquarters, and cast members were chauffeured about in a car that had belonged to Hitler’s foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop. More than three years after the Allied bombing, Berlin was still a boneyard of gray, jagged, hollowed-out buildings, block after block, mile after mile. Unter den Linden, once the capital city’s most majestic boulevard, was bare now, its namesake linden trees destroyed or chopped down for firewood. The great Reichstag was an empty shell, the lush Hotel Adlon bombed out and boarded up. Out for a stroll one night, Ryan fell into a bomb crater.

The poverty on the streets was overwhelming: Germans clustered around the locations, pleading for work as grips or extras. One well-known theater actor offered to work for a pair of pants, then came back the next day and said he wanted food for his family instead. Granet gave him both, and a check. “It is hard to visualize a world where the standard of currency is simply the cigarette,” he wrote.12 Chocolate bars were equally prized, and Ryan used them to pay the woman who ironed his shirts. “There seemed to be very little bitterness on the part of the Germans who worked with us,” Ryan wrote. “A grip, hoisting a heavy prop one day, laughed and said, ‘There goes my 1,500 calories.’”13

Apart from soldiers and government staffers, most of the other Americans in Berlin were journalists, who congregated at the press club and treated the movie people with smirking condescension. “As our visit wore on, the frost melted,” Ryan would write. “Fortunately there were no jokers in our company. Nobody tried to dress up like Hitler and make a speech from the famous balcony. Nobody got drunk or was carted off to jail.”14 The Russians were suspicious when cast and crew arrived to shoot in the Soviet sector, though Ryan saw no evidence of the military might he had expected, “no streets bristling with machine guns, no bayonets — as a matter of fact, almost no Russians.”15 Their chilly reception contrasted sharply with the picture’s final scene, in which the American and the Russian mend their ongoing political quarrel with a brotherly wave outside the Brandenberg Gate.

The last week in Berlin the company enjoyed a picnic on the Rhine River, courtesy of the US Army, and a party at the press club, attended by reporters and military people. There followed another nine days of photography in Frankfurt and four more in Paris. According to Granet, Ballard and Korvin came to blows during one train trip. When the company arrived in London, Oberon refused to fly back to New York and persuaded Granet to send her, Ballard, and Ryan on the Queen Mary out of Southampton. News photographers snapped photos of Ryan, grinning angrily and fiddling with his hat, as he escorted Oberon through Waterloo Station.

Decades later, when the affair had become a distant memory, Ryan would share with Harold Kennedy, his theatrical colleague and drinking buddy, a curious anecdote about his Atlantic crossing with a beautiful costar and her cameraman husband. As Ryan framed it, the woman had been making passes at him throughout the journey and cornered him late one night as he was taking the air on deck; getting no response to her come-ons, she pounced, knocked him down, and refused to let him up. Suddenly her husband “materialized on the deck, lifted her up, reached down and took hold of Bob’s shoulder, assisted him to his feet, and then, after apologizing to him profusely, blackened both of the lady’s eyes.”16

Ryan had an Irishman’s way with a story — he wasn’t the sort of man to stand by while someone was hitting a woman — but then Granet also reported rumors of noisy fights between Ballard and Oberon on the voyage home, and said that she returned to Hollywood with broken teeth. Ryan was staying on in New York for a few days to do promotional work for Crossfire. When the Queen Mary docked on Tuesday, September 9, the first thing he did was to call Jessica in Los Angeles. She put Tim on the phone to hear his father’s voice, and she must have informed Ryan, if she hadn’t already, that she was expecting another child.

WHILE RYAN WAS IN EUROPE, Crossfire had exploded. The picture opened in late July at the Rivoli, a 2,092-seat movie palace on Broadway, and broke box office records in its first week. “One of the most startling pictures ever to come out of Hollywood,” wrote the New York Morning Telegraph. “A film to be praised, praised again, and seen by all,” wrote the New York Post. “An important, stirring film,” declared the Daily Mirror. “Robert Ryan gives one of the performances of the year.”17 The picture had transformed his reputation overnight: critics and colleagues who had regarded him as a confident but unspectacular leading man now recognized him as an exciting, first-class character actor. There was talk of an Oscar nomination. “I came back to the sort of reception reserved by the New York press for people who had done something,” he later recalled. “Everybody wanted an interview; photographers were everywhere.”18

Ryan made a rare personal appearance at the Rivoli, where Crossfire was in its eighth week. “It was the first time I had seen the picture with an audience, and I was elated at the reaction,” he said. Afterward, when he was introduced to the crowd and walked onstage, the room suddenly quieted. Monty was the black, unfathomable heart of the picture; moviegoers who reacted to the anti-Semitism in Crossfire inevitably zeroed in on Ryan as the embodiment of all that fear and hatred. “I’m really not that kind of a guy,” he said, bringing down the house.19

By fall Crossfire had gone into general release and was performing well across the country, racking up impressive numbers not only in the more liberal metropolitan centers but in many small towns and in such conservative communities as Memphis, Omaha, and Oklahoma City. The RKO sales force played down the picture’s anti-Semitic angle, stressing the mystery element and Ryan’s costar Robert Mitchum, whose popularity was on the rise. There were pockets of resistance — “We never have had any racial troubles in this town and I don’t want to put anything before the people that might put ideas into their heads,” declared one theater owner — but RKO pursued a sharply effective strategy of establishing the picture in one cluster of towns and then expanding it to the next.20

Given the taboo-smashing nature of the story, some conflict was inevitable. The US Navy found the idea of an American soldier murdering a Jewish civilian so inflammatory that it banned Crossfire, refusing to screen it for troops at bases foreign or domestic. The army allowed it to be shown to soldiers at home but nixed any screenings overseas, arguing it might be seen by foreigners on the bases and reflect poorly on the United States. The Motion Picture Export Association, which cleared movies for the international market, turned down Crossfire, citing the same concerns. And though most leaders of the American Jewish community hailed the picture — in Chicago, the Anti-Defamation League had launched a vigorous campaign encouraging local lodges to sponsor private screenings for civic leaders — some argued that Crossfire might harden anti-Semitic feelings and even provoke bigots to violence.

This opinion emerged most strongly in the American Jewish Committee’s monthly magazine Commentary. Editor Eliot Cohen noted the malign magnetism of Ryan’s hypnotic performance: “You’re drawn to him. He’s big, he catches your eye. His personality overshadows the others. A plain, husky fellow, not much education, visibly troubled, up against a world too smart for him, fighting shrewdly, stupidly, blindly against the ‘others’ who hem him in — before his crime, after his crime. (For the millions near enough like him to identify with him, will Montgomery be the simple bully and villain the producer intended, assuming that was his intention? The chances are just as good that he will be taken as a kind of hero-victim — the movie equivalent of the Hemingway-Faulkner-Farrell male, hounded and struck down by a world he never made.)”21

Ryan was less concerned with anti-Semites or the Jews they hated than with the much larger middle ground of Gentiles who were innocent but ignorant. “What I hope for is that the mass of Americans — those who have never come directly, first-hand, against intolerance — will think about those who daily are exposed to it, and will reflect on their actions to those groups in a new light,” he wrote in the Daily Worker. “Most Americans aren’t intolerant, but neither are they concerned with those who are. Pictures like this will help show how senseless, how ignorant, how detrimental to fundamental American principles … any kind of bigotry is. When people fully realize that, they will stop the careless thinking and the even more careless talk.”22

One thing Ryan had understood better than the friends who had discouraged him from playing Monty: a controversial role can help an actor’s career. Ray Milland had won an Oscar playing a raging alcoholic in The Lost Weekend (1945). Yet, as Ryan pointed out in yet another first-person piece about Crossfire, Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage had never been filmed because no movie star wanted to play a coward.* “The controversial role, like no other, can meet the needs of the actor who feels the void of not achieving professional stature,” he wrote, inadvertently revealing the career frustration that had driven his choice. “It gives one the feeling of accomplishment, of acting with a purpose.”23 When he reflected on the risk taken by Dore Schary, Adrian Scott, Eddie Dmytryk, and John Paxton, who had dreamed up the picture, his own gamble paled in comparison.

Ryan looked forward to more such projects, but the political winds were shifting. That fall Schary was approached by two investigators from the House Un-American Activities Committee — “rather gray-looking gentlemen,” he wrote.24 The committee was moving forward with its hearings into communist infiltration of the movie industry, and they wanted to know if he might have any relevant information about Ryan. Schary pointed out that Ryan was a former marine, a credential he felt spoke for itself. They asked him about Scott and Dmytryk, the producer and director of Crossfire. They requested screenings of Crossfire and The Farmer’s Daughter, a Loretta Young comedy that RKO had released in March, and afterward they declared both pictures to be “pro-Communist.”25

Schary later wrote that he gave the investigators nothing and expressed his lack of regard for the committee. On September 22, Schary, Scott, and Dmytryk all received subpoenas to testify in Washington. Forty other Hollywood professionals were summoned as well, ranging from such right-wingers as Adolphe Menjou, Ayn Rand, Leo McCarey, and Walt Disney to such left-wingers as Charles Chaplin, Clifford Odets, Robert Rossen, and Bertolt Brecht. The Red-baiting Hollywood Reporter labeled nineteen of the forty-three — including Scott and Dmytryk — as “unfriendly” witnesses on the basis of their previous public statements about the committee. The hearings would convene a month later.

Ryan always would attribute his narrow escape from the blacklist to his war record and his Irish-Catholic heritage (the committee’s equation of communists and Jews was well known). He had just been investigated by the FBI and cleared for travel in the Soviet sector of Berlin. The fact was that Scott and Dmytryk had been Communist Party members, whereas Ryan (for all his willingness to publish in the Worker) was a solid Democrat who could always be counted on to inject a note of ward-heeling realism into the unmoored radicalism of friends and colleagues. During this period, Jessica would write, he had “his first brush with the doubletalk, the rigid doctrinaire attitudes, the attitude of take over or destroy, of some people involved who were or had been truly Communist-minded. At the same time he would not nudge one inch from the position of defending their right to believe as they did.”26 Ryan quickly threw in with the Committee for the First Amendment (CFA), an organization formed by his screenwriter pal Philip Dunne, as well as John Huston and director William Wyler, to protest the hearings.

Wyler hosted an overflow meeting of the new group at his Beverly Hills home in early October. Outside, FBI agents took down license plate numbers,27 yet the CFA was a safely liberal group: it defended civil liberties in general, not the “Hollywood Nineteen” in particular, and the founders actively discouraged communists and fellow travelers from joining. The group resolved to protest the congressional probe in full-page newspaper ads and organized a large delegation of celebrities to fly east for the hearings. Ryan was stuck in town shooting interiors for Berlin Express, but he agreed to take part in Hollywood Fights Back, a pair of radio programs to be broadcast nationwide on October 26 and November 2.

Even before that, on Wednesday, October 15, Ryan appeared at the giant “Keep America Free!” rally at the Shrine Auditorium, which benefited a defense fund for the Nineteen. Presented by the Progressive Citizens of America (PCA) — a more radical group that was the Communist Party’s last real lobbying presence in Hollywood — the rally drew some seven thousand people.28 “We protest the threat to personal liberty and the dignity of American citizenship represented by this police committee of Dies, Wood, Rankin, and Thomas,” Ryan declared, naming the congressmen on the committee as he read a proclamation from the PCA. “We demand, in the name of all Americans, that the House Committee on Un-American Activities be abolished, while there still remains the freedom to abolish it.”29

The following Monday the hearings commenced in the Caucus Room of the Capitol Building, with every seat filled and the proceedings recorded by newsreel cameras, nationwide radio, and a battery of reporters and press photographers. J. Parnell Thomas, the New Jersey Republican who had assumed chairmanship of the committee with the Eightieth Congress, presided over the hearings, which got off to a bang when studio head Jack Warner volunteered the names of twelve people who had been identified as communists and fired from Warner Bros. His action stunned the Hollywood community, especially his colleagues at the Motion Pictures Producers’ Association (MPPA), which had agreed to close ranks against the committee. As the week progressed, the committee called a succession of friendly witnesses, who named some three dozen people as communists.

The week’s events failed to dent the enthusiasm of the Committee for the First Amendment, whose members took heart from editorials condemning the hearings in the New York Times, the Washington Post, and other dailies. On Sunday morning the CFA’s star contingent — including Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Myrna Loy, Gene Kelly, Judy Garland, and Danny Kaye — took off for New York and then Washington, having already recorded their contributions for the Hollywood Fights Back broadcast. Ryan delivered his thirty-second bit live in the studio: “President Roosevelt called the Un-American Committee a sordid procedure, and that describes it pretty accurately,” he declared. “Decent people dragged through the mud of insinuation and slander. The testimony of crackpots and subversives accepted and given out to the press as if it were the gospel truth. Reputations ruined and people hounded out of their jobs.”30

The tide of public opinion began to turn against the Nineteen on Monday morning, when writer John Howard Lawson accused the committee of Nazi tactics, was charged with contempt of Congress, and had to be forcibly removed from the chamber. As all this was going on, Dmytryk turned to Schary and asked, “What are my chances at the studio now?”

“You have an ironclad contract,” Schary replied.31

Adrian Scott brought a four-page statement defending Crossfire and noting the anti-Semitism of Mississippi Democrat John E. Rankin, a committee member, which Thomas refused to let him read. Both Scott and Dmytryk were asked repeatedly if they were communists; they declined to answer, citing their Fifth Amendment rights, and were charged with contempt. Schary, asked if he would knowingly employ communists at RKO, replied that he would, “up until the time it is proved that a communist is a man dedicated to the overthrow of the government by force or violence, or by any illegal methods.”32

Seven more unfriendly witnesses defied the committee and were cited for contempt, among them screenwriter Dalton Trumbo — whose wartime romance Tender Comrade (1944), directed by Dmytryk, had given Ryan his first big break. The committee had absurdly labeled the movie communist propaganda for its story of four women sharing a house while their men fight in World War II. When Thomas suddenly suspended the hearings on October 30, with Brecht having broken rank and eight witnesses still to be heard, Variety reported that one factor was the reluctance of several committee members to release a long-promised list of subversive pictures. Once these innocuous and well-known titles were made public, the members argued, the committee would become “a laughing stock.”33

If Ryan was afraid of the committee, he didn’t show it: while the hearings were in progress, he and his Crossfire costar Gloria Grahame spoke at the annual convention of the American Jewish Labor Council, which would turn up on the US attorney general’s list of communist (but not subversive) organizations.34 The studio moguls, however, were badly spooked by the hearings. On November 24 — the same day the House of Representatives voted 346 to 17 to uphold the contempt citations — the Motion Picture Producers’ Association met at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York to hammer out a strategy. President Eric Johnston insisted that the studios purge their ranks; Schary led the charge against him, backed by independent producers Samuel Goldwyn and Walter Wanger, but Johnston carried the day. The MPPA announced that members would no longer employ known communists and would fire the unfriendly witnesses (now labeled the Hollywood Ten), whose actions “have been a disservice to their employers and have impaired their usefulness to the industry.”35

RKO was the first studio to act, firing Scott and Dmytryk. Schary refused to drop the ax, so Floyd Odlum, chairman of the board, handed the job to Schary’s boss, RKO president Peter Rathvon. Every studio contract included a vaguely worded morals clause allowing the studio to terminate any employee deemed to have disgraced the company. Barred from the lot, their current projects canceled or reassigned to other producers, Scott and Dmytryk turned their attention to the pressing matter of defending themselves against the contempt citations, which could land them in federal prison.

Support for the unfriendly witnesses wilted. Humphrey Bogart, whose iconic tough-guy persona had been a potent weapon for the CFA, issued a statement describing the PR tour to New York and Washington as “ill-advised and even foolish.”36 He had never been a communist or communist sympathizer, he declared, and he detested communism. The statement caused a collective shudder in Hollywood — if a star of Bogart’s magnitude felt the need to distance himself from the Ten in such strident terms, could anyone be safe? Donations to the Committee for the First Amendment dried up immediately, and members reported pressure to resign. Within three months the organization would fold.

Amid all this, Berlin Express was still shooting on the RKO lot. The picture’s final scene, with the American and the Russian expressing their fellowship outside the Brandenberg Gate, must have seemed like fantasy now. Closer to the mark was the little speech delivered to the kidnapped peacemaker by the malevolent leader of the right-wing underground: “I too believe in unity. But unlike you I know that people will only unite when they are faced with a crisis, like war. Well, we are still at war; you are not. So we are united; you are not. So we will succeed; you will not.”

RYAN LIKED TO TELL INTERVIEWERS he wasn’t “a chaser” (which was true — the way women responded to him, he never had to chase anyone). For a man so proud of his family, the affair with Merle Oberon was a strange anomaly, an ongoing adulterous relationship that became an open secret among the cast and crew. Charles Korvin contended that the affair continued on the RKO lot, though production records suggest some turbulence as the picture was drawing to a close. On Wednesday, November 5, Oberon went home sick at noon, forcing Tourneur to scrap the rest of the day’s scenes. The following Monday she didn’t show up for work, and that Friday she left in the middle of the afternoon. According to biographers Higgins and Moseley, she and Ryan never saw each other again after Berlin Express,37 though Ryan and Lucien Ballard would make four more pictures together.*

Somehow RKO managed to keep the whole mess out of the scandal sheets; however, the much-feared gossip columnist Louella Parsons twitted Ryan about it in a February 1948 profile. (“There had been a lot of talk about feuding in the ‘Berlin Express’ troupe, and I asked Bob if that were true,” wrote Parsons. “I had heard that he and Merle Oberon had been particularly bitter in their quarrel.”)38 From that point on, Ryan’s movie-magazine pictorials stressed fatherhood, with Tim becoming a frequent participant. How Bob and Jessica dealt with the affair would remain private, but soon after he returned from Europe, they decided to buy a house in the San Fernando Valley, far from the Hollywood social scene.

A certain amount of hobnobbing was required to keep one’s career going, but Jessica didn’t like actors or the parties they threw. “As a wife, you met the same people over and over again,” she wrote in a later memoir, “because they didn’t recognize you unless you were standing right beside your husband, and even then they weren’t always sure you were the wife. It was spooky.” By now she had published her second mystery for Doubleday and was working on a third, but no one was interested in that. She would start conversations with people and then see their eyes darting about in search of someone more important. “If you were a wife you got very tactful about releasing any poor sap quickly to go do business … and then ended up sitting tensely with other tense wives trying their best to look as if they were having a good time.”39

She reached her limit one night when she and Robert attended a swank party and she was immediately shunted off to the side with her friends Amanda Dunne and Joan Houseman. Robert, Philip Dunne, and John Houseman were off somewhere having lively conversations. “That night Joan Houseman’s solution to the condition of non-being was to retreat to a corner of the vast living room of the vast house and get quietly smashed,” Jessica wrote, “while she stared at the crowd with an expression of splendid French contempt.”40 Amanda and Jessica began tossing back drinks as well, until Amanda stood up suddenly, looking as if she might be ill, and went off in search of a bathroom.

Left alone, Jessica strolled into the host’s library to find some reading material, and before long Amanda burst into the room, looking rather crazed. “There’s a room full of dead animals out there!” she exclaimed. Jessica followed her back into a coatroom where all the women’s furs were hung. This was too much for Jessica, and she told Robert she was going out for some air. “Once outside in the car, I went quietly into hysterics,” she wrote. “The condition of non-being produces intense anxiety.”41

On Kling Street, just east of Cahuenga Boulevard in North Hollywood, the Ryans found an A-frame ranch house with a paved terrace and a bare, spacious yard. “It was the biggest house we could get with the most ground for the least money at a time when we still did not trust — I didn’t trust — that the money would keep coming in,” Jessica wrote. “Robert never doubted it, but he had never been as poor as I had been.”42 The couple landscaped the place themselves (planting ivy that eventually ran riot over the house) and began adding wings. The shed in the backyard was converted into Ryan’s private office and workout room. This was the first time Ryan had actually owned a home — his parents had rented all their lives — and the suburban locale suited his reclusive nature.

The place was modest but comfortable, with plenty of room for the kids to run around; he and Jessica installed a sandbox, a swing set, and a wading pool. “Facing the garden is a wide, airy living room with almost one whole wall of glass, opening onto the terrace,” noted a visiting journalist. “A beautiful antique chest dominates one end. The chairs and divans are tailored and comfortable; the tables low and wide … The muted greens and grays and blues of walls, carpets, and upholstery are brightened by huge bouquets of fresh garden flowers.”43

Ryan made sure the reporter understood that social gatherings at their home were limited to their close circle of friends, not the movers and shakers of the picture business. He and Jessica were perfectly happy with each other’s company. Philip Dunne would marvel at Ryan’s “tremendous devotion to his family. He was the most family-oriented man I ever knew.”44

Ryan tending to chores at the new house on Kling Street in North Hollywood. His years there with Jessica and their young children were among his happiest. Robert Ryan Family

In December 1947, Ryan made a quick trip to Chicago to address the national Conference of Christians and Jews, pinch-hitting for Dore Schary. “He began to be asked to speak before Jewish groups to discuss anti-Semitism,” Jessica recalled. “In the beginning, the doing of it appeared to be for publicity for the movie … but when that phase was over, they wouldn’t let him go. For a long time there he was playing what he called the Synagogue Circuit.”45

From there Ryan flew to New York to see some plays. Since Crossfire had hit, he had been fielding offers from Broadway, but his calendar for 1948 already was filling up with pictures. RKO announced that he would costar with Cary Grant, Frank Sinatra, and Robert Mitchum in Honored Glory, an episodic drama about nine unidentified men, killed in action during World War II, whose stories make them candidates for the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (the film would never be made).46 MGM wanted to borrow Ryan for the revenge drama Act of Violence. And Schary, who had been trumpeting Crossfire as proof that A pictures could be made on B budgets, was ready to move forward with his next such experiment: The Set-Up, a boxing drama about a washed-up fighter staring down his bleak future. The source material was Joseph Moncure March’s narrative poem of the same title, a favorite of Ryan’s at Dartmouth.

His first assignment that year was RKO’s antiwar parable The Boy with Green Hair, adapted from a short story by Betsy Beaton. Filmed in Technicolor, it starred eleven-year-old Dean Stockwell as a schoolboy who has been passed from relative to relative while his parents are overseas.* Eventually he lands in a bucolic small town with a kindly old Irish-American gent (Pat O’Brien) and begins to make a life for himself, but then he learns the truth about his parents — they were killed in London during the blitz — and the trauma turns his hair green overnight.

The project had originated with Adrian Scott, himself the adoptive father of a traumatized British war orphan; but after Scott was fired by RKO, Schary handed The Boy with Green Hair over to producer Stephen Ames and firsttime movie director Joseph Losey. A senior at Dartmouth when Ryan was a freshman, Losey had studied with Bertolt Brecht in Germany and in 1935 had traveled to the Soviet Union, where he staged Clifford Odets’s Waiting for Lefty in Moscow. His latest theatrical project had been an acclaimed Broadway production of Brecht’s Galileo, performed in English for the first time and starring Charles Laughton.

Fresh from the rubble and hungry children of Frankfurt and Berlin, Ryan couldn’t have been more sympathetic to The Boy with Green Hair. His second-billed part consisted of only one extended scene with Stockwell, which took two days to shoot; even so, it would remain one of the picture’s best-liked sequences. At a police station one night, cops fire questions at Peter, the brooding and now bald-headed boy. Ryan plays Dr. Evans, a laid-back child psychologist who arrives with a brown-bag dinner and asks the cops to leave them alone. Children who grew up around the actor would remember his uncondescending manner toward them, and he incorporates it here to fine effect. Evans wordlessly changes the lighting in the room, taking an overhead spot off them, and asks Peter to move to a chair so he can have the bench for his dinner. “Chocolate malted milk,” he notes, frowning into the cup. “I’m sure I asked for strawberry.” They both know it’s a game, but Peter is starving; he takes the malted and digs into a hamburger, and his responses to the doctor’s questions trigger a series of flashbacks.

The Boy with Green Hair can be cloying and moralistic, but there are genuine moments of fear and anger as well. Peter, having learned of his parents’ death, is stocking shelves at a local grocery and overhears three women debating the Cold War. Losey follows his face, shooting him through cabinets and shelves as the women’s voices hover off-screen. “People say another war means the end of the world,” says one. “War will come, want it or not,” her friend replies. “The only question is when.” A third adds: “Just in time to get more youngsters like Peter.” This so frightens the boy that he drops a bottle of milk, which smashes on the floor. A low-angle shot shows the three ladies gathered above, grinning in amusement.

The central scene is a powerfully weird and stylized dream sequence in which Peter awakes in a forest clearing and encounters the very war orphans he and his classmates have been studying on posters in school. One girl has lost a leg; another holds an Asian infant. The oldest orphan explains to Peter that his green hair marks him as a messenger: “You must tell all the people — the Russians, Americans, Chinese, British, French, all the people all over the world — that there must not ever be another war.”

The Boy with Green Hair crystallized a public sentiment for world government that had been growing in the United States since the end of the war. Norman Cousins, editor of the Saturday Review of Literature and a founder of the United World Federalists, had framed the issue before any other journalist. His celebrated editorial “Modern Man Is Obsolete,” written the night after Hiroshima was destroyed, argued that the event marked “the violent death of one stage in mankind’s history and the beginning of another.” Now that man had the power to incinerate whole cities, he would have to evolve past the need for war, which would mean eradicating global inequality and establishing world government. To this end, Cousins wrote, modern man “will have to recognize the flat truth that the greatest obsolescence of all in the Atomic Age is national sovereignty.”47 By 1946 a Gallup poll found that 52 percent of Americans favored the liquidation of the US military in favor of an international peacekeeping force. Ryan was one of them, and he would get to know Cousins later that year when he joined the Federalists, a rapidly growing organization that advocated “world peace through world law.”

The week before Ryan shot his scene for The Boy with Green Hair, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced the Oscar nominations for 1947. Crossfire was honored in five categories: best picture, best director, best screenplay, best supporting actress (Grahame), and best supporting actor (Ryan). But as more than one industry observer noted, this good fortune put RKO in a ticklish position, given that it had fired the picture’s producer and director. There was another twist as well: in every category except Ryan’s, Crossfire was competing with Gentleman’s Agreement, the Fox production Schary had beaten to the box office by four-and-a-half months. Released in December and carefully marketed with Crossfire as its model, Gentleman’s Agreement was still doing big business across the country and had topped the nominations race with a total of eight.

Jessica and Robert attend the 1948 Academy Awards ceremony. “We don’t ask actors home,” she would later write. “We haven’t, Robert or I, much to say to them privately.” Franklin Jarlett Collection

Though RKO had beaten Fox to the punch, Gentleman’s Agreement had effectively stolen Crossfire’s thunder as an exposé of anti-Semitism, to Ryan’s great irritation.48 Adapted from a novel by Laura Z. Hobson, it starred Gregory Peck as a journalist who poses as a Jew in order to write a magazine story. In some respects Gentleman’s Agreement was bolder than Crossfire; it confronted prejudice head-on instead of sneaking it into a murder mystery, and in contrast to the other film’s psychopathology, it revealed more casual and insidious forms of bigotry. It was also the kind of picture Academy voters could feel good about honoring: this was no crummy little crime story shot on borrowed sets, but a big, long prestige drama set in the penthouses and boardrooms of Manhattan, produced by the great Darryl F. Zanuck.

The other nominees for best supporting actor were Charles Bickford as the starchy butler in RKO’s The Farmer’s Daughter, Thomas Gomez as the warmhearted carny in Universal’s Ride the Pink Horse, Richard Widmark as the giggling killer in Fox’s Kiss of Death, and Edmund Gwenn as Kris Kringle in Fox’s Miracle on 34th Street. Ryan relished the attention, though his chances of winning seemed fairly slim: he would be dividing the psycho vote with Widmark, and really, who was going to choose a Jew-hating murderer over Santa Claus?

Cheyney Ryan arrived on March 10, at Cedars of Lebanon Hospital in Los Angeles, and ten days later Jessica had recovered sufficiently to accompany her husband to the Shrine Auditorium. As most had predicted, Gwenn won best supporting actor. Crossfire was shut out by Gentleman’s Agreement, which took best picture, best director (Elia Kazan), and best supporting actress (Celeste Holm). According to Dmytryk, the right-wing Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals had conducted a vigorous campaign against Crossfire.49 The picture had made the year-end lists of all the major critics and collected honors ranging from an Edgar Allan Poe Award (for best mystery film) to a Cannes Film Festival award (for best social film). But in Hollywood, Crossfire was still a double-edged sword. A few months earlier, when MPPA president Eric Johnston had praised the picture in a speech, the legal counsel for the Hollywood Ten had puckishly invited him to serve as a character witness for Scott and Dmytryk. Johnston declined.

*In response to my Freedom of Information Act request, the FBI reported that its central records system contained no file for Ryan.

*Cinematographers still refer to this device as “the obie.”

*When John Huston finally brought the novel to the screen in 1951, his star was the legendary war hero Audie Murphy.

*Inferno (1953), The Proud Ones (1956), Hour of the Gun (1967), and The Wild Bunch (1969).

*Stockwell had just won a special Golden Globe Award for his performance as Gregory Peck’s son in Gentleman’s Agreement.