Читать книгу The Lives of Robert Ryan - J.R. Jones - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеtwo

The Mysterious Spirit

She was gorgeous. Five-foot-seven at least, with dark red hair and cutting, observant brown eyes. Ryan first spotted her in the hallway of the Max Reinhardt School of the Theater on Sunset Boulevard. He had arrived in Los Angeles to discover that the theater school at the Pasadena Playhouse was full, but a fellow named Jack Smart, whom he had met through a girlfriend in Chicago, recommended the Reinhardt School, which had opened just that summer. As Ryan liked to tell it, he decided to enroll the moment he saw the girl in the hallway. Through a school administrator he managed to arrange an introduction; her name was Jessica Cadwalader, she was studying acting as well, and they would begin classes together the next day with Professor Reinhardt. Feeling impetuous, Ryan asked her to dinner, and she accepted.

Jessica Cadwalader was twenty-three, born in Los Angeles to Quaker parents and, after they divorced, raised in Berkeley by her mother. She had graduated from the private Anna Head School, where she had been a tennis champ, and shortly thereafter she boarded a bus for New York City, where she found an apartment in the Murray Hill neighborhood of Midtown Manhattan, took modeling jobs through a Park Avenue agency, and tried to establish herself as an actress under the name Jessica Cheyney. For some time she had performed with the Wayfarers, a theater group in San Francisco. Now she was back in Los Angeles looking for movie work; she had been an extra in the W. C. Fields comedy Poppy (1936) and gotten a line, only to see it cut, in the Gary Cooper drama The Adventures of Marco Polo (1938). She was formidably well read despite the fact that she had never attended college, and she looked a little startled at dinner when Ryan informed her that the piece he had been rehearsing for the first class was no less than Hamlet’s second soliloquy. He wanted to get Reinhardt’s attention.

As Jessica already knew, Reinhardt’s attention was a force to be reckoned with. Quiet and stout, with hypnotic blue eyes, the aging Austrian studied you so intensely, and listened with such force, that he seemed to be penetrating your very soul. Reinhardt had made his name in Europe and the United States with spectacular, expressionist stagings of Everyman (for the Salzburg Festival, which he cofounded in 1920 with Richard Strauss), The Miracle, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. His 1934 production of the latter at the Hollywood Bowl became the talk of the town, and the following year Warner Bros. hired him to direct a lavish screen version with James Cagney, Olivia de Havilland, and Mickey Rooney. Born to Jewish parents in Austria-Hungary, Reinhardt had fled the Third Reich in 1938 and settled in Los Angeles. Though he never managed to land another movie assignment, he continued to direct stage productions on both coasts; in fact, the new school would serve as a workshop for plays he wanted to mount commercially.

Jessica braced herself the next day as her new friend from Chicago came forward to butcher Hamlet’s second soliloquy: “O villain, villain, smiling, damned villain! My tables — meet it is I set it down / That one may smile, and smile, and be a villain!”1 Reinhardt’s only response was, “With training …”2 Ryan took this as a great triumph when Jessica spoke to him afterward. “There is a young man who has just enrolled that I like very much,” she reportedly wrote to her mother, “but he’s the worst actor I’ve ever seen in my life.”3

Meeting with Ryan later, Reinhardt told the young man he had a quality that reached out over the footlights, and with enormous work and commitment he might one day become a great performer.4 These were the right words coming from the right man at the right time, and from that moment onward Ryan entrusted himself to Reinhardt. “Max Reinhardt was not only my first teacher,” he would write near the end of his life (forgetting Ed Boyle in Chicago), “but remains to this day, thirty-two years later, the most tremendous and important person who has ever influenced my career and my work.”5 Though Reinhardt was best known for his elaborate productions, incorporating music, choreography, and lighting effects, Ryan saw that the old man was also deeply and personally invested in his smaller projects. “His own obsession was the inner life of man,” Ryan wrote, “the mysterious spirit that both flickers and flames in all of us.”6

Reinhardt felt that human emotion was stifled by bourgeois life. “Unconsciously we feel how a hearty laugh liberates us,” he wrote in an essay on acting, “how a good cry or an outbreak of anger relieves us. We have an absolute need of emotion and its expression. Against this our upbringing constantly works. Its first commandment is — Hide what goes on within you. Never let it be seen that you are stirred up, that you are hungry or thirsty; every grief, every joy, every rage, all that is fundamental and craves utterance, must be repressed.”7

How profoundly this idea must have struck his new student from Chicago, this powerfully built but painfully shy man whose parents had shown him the good life but always taught him to keep his feelings to himself. “Only the actor who cannot lie, who is himself undisguised, and who profoundly unlocks his heart deserves the laurel,” Reinhardt wrote.8 Not until years later, after working with numerous pedestrian directors, would Ryan recognize what an enormous gift Reinhardt had given him so early in his development. Yet implicit in that gift lay a great moral and emotional challenge.

Reinhardt cut an imposing figure, yet he tended to put people at ease because he listened so closely. “He never listened passively,” recalled the composer Bronislaw Kaper, “he listened actively, with the greatest interest reflected in his eyes and his half open lips.”9 In fact, Reinhardt’s ability to listen defined his whole approach to acting. “The best piece of advice I’ve ever received as an actor was given me by Max Reinhardt,” Ryan told a reporter years later. “He put it in one word — ‘Listen.’ If you really hear what other actors say to you, your own reaction and the proper reading of your lines will be easy.”10

Actors who worked with Reinhardt, among them Stella Adler and Otto Preminger, testified to his talent for bringing an actor out of himself, quite literally — for locating personal traits that one might heighten and project onstage. If you engaged Reinhardt imaginatively, he invested himself in your performance, and you immediately felt the thrill of shared discovery. “He was most effective when he liked an actor, and perhaps only when he liked him,” remembered Preminger. “If he felt that the actor really wanted to be directed by him, then his imagination, the variety of advice, the way he worked the actor in the scene and for the scene, was just fantastic. I don’t think any director ever had that gift. Maybe it was because he was an actor originally.”11

The Reinhardt School offered a well-rounded education, and Ryan threw himself into his studies, learning about lighting, set design, and direction. But acting was his great love now. His workshop teacher, Vladimir Sokoloff, had performed with the Moscow Art Theatre under the great director Constantin Stanislavski, and from him learned the principle that movement expressed a character’s motivation better than anything else. Yet Sokoloff’s classes were more traditional than the Stanislavski-inspired “method acting” then gaining traction at the Group Theatre in New York, in which the performer used powerful personal memories to trigger onstage responses. “ ‘The Method’ would have driven Sokoloff out of his skull,” Ryan later mused. “He taught action, not ‘memory of emotion.’”12

Under Sokoloff’s instruction the young man improved rapidly, and during the fall 1938 semester Reinhardt cast him as Silvio and Jessica as Beatrice in a workshop production of Carlo Goldoni’s At Your Service. Ryan played Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and the father in Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, “at one of whose unforgettable rehearsals,” wrote Gottfried Reinhardt, “my father showed Bob Ryan how literally to collapse after the discovery of his daughter in a brothel, how to fold up like a jackknife and to exit, his torso bent horizontal, a destroyed human being.” Clearly Reinhardt appreciated the physicality of this boxer who had graduated to the stage, and Ryan would embrace the idea of movement as character.

ALL THROUGH this great artistic awakening, Ryan was falling in love with Jessica Cadwalader. Their courtship took a rocky turn when he invited her to dinner at the Brown Derby and a miscommunication resulted in each of them sitting alone, waiting for the other to materialize, on successive days. When he called her to complain about being stood up, she hung up on him and went to San Francisco with a girlfriend. But before long the two thespians had become inseparable, going out for drinks when they could afford it or talking all night about books and movies and politics and, of course, acting. Ryan had never met anyone like her; she was introverted, but smart as a whip and passionately idealistic. The more time he spent with her, the more he wanted her in his life. For some reason she always called him Robert; friends and family had called him Bob for years, but to Jessica he would always be Robert Ryan.

Ryan might have thought he had experienced the West in his Montana adventures, but Jessica’s people were real westerners. Her maternal grandmother, Anno, told Jessica all about the old days. Born Annie Neal in 1859 to an undertaker in Atchison, Kansas, she had been worshipping at the town’s Episcopal church one Sunday morning when she met George Washington Cheyney, a young Philadelphian five years her senior whose wealthy family, alarmed by his indolence, had set him up as manager of a silver mine that some of his father’s colleagues owned in Tombstone, Arizona. On his travels back and forth, George Cheyney changed trains in Atchison, and before long he and Annie had married and moved to Tombstone, to a large house on the hill overlooking the town.

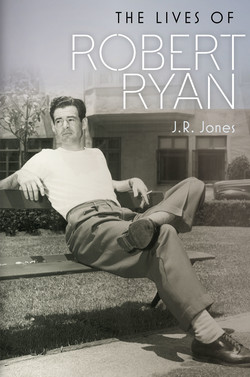

Jessica Cadwalader (late 1930s). Ryan met her in the lobby of the Max Reinhardt School of the Theater on Sunset Boulevard; they spent the next thirty-three years together. Robert Ryan Family

By then Tombstone was the fastest-growing boomtown in the Southwest, with a fair amount of culture alongside the roughnecks who poured in hoping to strike it rich. There were decent restaurants, an ice cream parlor, and opera performances at Schieffelin Hall, named for the prospecting family that had founded the town. Jessica pressed her grandmother for details about the famous shootout at the OK Corral in 1881. “I never knew anything about all that riff-raff,” Anno replied. Her husband “did not think such goings-on should be talked about in front of ladies.… I have a feeling George said it was good riddance to bad rubbish.”13 Later Jessica dug up a history of Tombstone that described one George Cheyney ducking behind a counter during the armed robbery of an assayer’s office.

As superintendent of the Tombstone Mill and Mining Company, George Cheyney branched out from Tombstone and developed a new mine in the Oro Blanco Mining District, but in the late 1880s Tombstone’s mining industry collapsed after the miners began to hit water and the town’s pumping plant was destroyed in a fire. George ran for Congress as a Republican in 1890 and served as school superintendent for the territory, then moved his family to Tucson, where he was appointed postmaster in 1898 and four years later ran a successful campaign for probate judge. Shortly after his election George traveled to San Francisco, seeking treatment for a liver ailment from a Tucson physician who had moved there, and died at age forty-nine from cirrhosis.

Three years later his second daughter, Frances — Jessica’s mother — married Richard Bacon Cadwalader, a young Quaker in his early twenties who had come West from Cincinnati with his mother, Ella Bacon Cadwalader, after suffering a nervous breakdown in his first semester at Harvard. Ella Cadwalader fought against the union between Richard and Frances, but when Anno traveled from Tucson to Los Angeles to visit her sister, she took the young lovers along and had them married by an Episcopal clergyman. This would have been the ultimate horror for Ella and her husband, Pierce Jonah Cadwalader, whose family had followed the Society of Friends since the seventeenth century and been part of the influential Philadelphia Quakers Meeting.

In 1907, Frances gave birth to a son, Richard Jr., and seven years later, on October 26, 1914, Jessica Dorothy Cadwalader arrived. The family was living in Tucson when Richard Jr., only ten years old, died of influenza in September 1917 (just three months earlier, little Jack Ryan had succumbed in Chicago). Jessica grew up an only child, an introvert, and a voracious reader, closely instructed in her religious beliefs by her great aunt Dora, whom she remembered as “a great and determined Quaker lady.”14 From childhood Jessica learned to value peace over war, mercy over revenge; she learned that God’s spirit, dwelling within her, not only permitted but obliged her to work for peace. Dora liked to recite the “Quality of Mercy” speech from The Merchant of Venice, in which Portia describes mercy as “twice blest: / It blesseth him that gives and him that takes.”15

Since the beginning the Society of Friends had preached the equality of men and women, allowing women into ecclesiastical positions, and in America the Quakers had provided not only the idealism but also some of the early leaders of the women’s movement: the Philadelphia abolitionist Lucretia Mott, who had helped organize the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention on women’s rights; the great speaker and activist Susan B. Anthony, who spent a lifetime trying to win women the vote; and Alice Paul, who helped pass the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 and wrote the Equal Rights Amendment proposed to Congress three years later.* Dora wanted Jessica to get a good education and become a lawyer like Dora’s brother, Jonah; there was no reason she should have to spend her life in her husband’s shadow.

ON SATURDAY, MARCH 11, 1939, Bob and Jessica exchanged vows at St. Thomas Episcopal Church in West Hollywood, with their mothers, the Reinhardts, the Sokoloffs, and about fifty of their fellow students attending (including Nanette Fabray, the other big star who would emerge from their graduating class). Anno must have been there as well, a reminder to Ryan of the iron female will surging through his bride’s family. A respectable matron in Tombstone and an example to her children in late middle age, Anno had decided upon her seventieth birthday to please no one but herself. “That evening she drank her first highball and smoked her first cigarette,” her granddaughter wrote. “She went on doing both to the end, chain smoking without inhaling, puffing out great clouds of smoke to wreathe her white head, looking like something between a Chinese ancient and an old madame, while the cigarette ashes spilled down the front of her massive bosom.”16

Two more productions — Goldoni’s Servant of Two Masters, which had been one of Reinhardt’s early triumphs, and Holiday, a romantic comedy by Phillip Barry that had become a screen hit for Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant — followed before the end of the year’s study, at which point the two newlyweds began to reckon with the question of money. As the story goes, word came shortly after their wedding that Ryan’s oil well in Michigan had run dry, which meant an end to their steady dividend.

They supported themselves as best they could: Ryan worked as an assistant director to Reinhardt and taught boxing lessons for a dollar a pop, but Jessica was the real breadwinner, modeling for a photographer and then hiring on with vaudeville producers Franchon and Marco as a chorus girl at the Paramount Theater. “It was a rugged job, and she hated it,” Ryan would write, “but it made it possible for me to work and study and pound on doors and try a little longer to make somebody believe I could really act.”17 The first agent Ryan approached told him to go out the door and come back in again. “Make an entrance. Get it?” When Ryan did, the agent said, “Go back to Chicago.”18

From the house they had rented after their marriage, they moved to a small cottage and then to an apartment above someone’s garage. Their situation was precarious, but Ryan was relatively sanguine. “I thought of what had happened to my father and knew that it was worse than useless to worry,” he recalled. “The moment I stopped worrying, things began to come right for us.”19

In late December 1939, Reinhardt cast Ryan in a commercial production of Somerset Maugham’s drawing room farce Too Many Husbands, to open the following month at the Belasco Theater in Los Angeles. Promoted as “a saucy comedy with music,” the play centered on a woman who believes her first husband has been killed in action during the Great War and takes a second, only to have the first return home; by then she has a child by each man. Marsha Hunt, a young actress who had recently signed to MGM, went to see a friend in the play and was struck by Ryan and the other male lead, former Olympic shot putter Bruce Bennett. “They were remarkable, both of them,” Hunt recalled. “Tall, wonderfully good-looking but, most of all, graceful in their movements onstage.”20 The engagement brought Ryan his first serious attention around town, and by the end of its run a casting director for Paramount Pictures had recommended him to director Edward Dmytryk for the lead in Golden Gloves, an upcoming picture about amateur boxing.

Golden Gloves told the story of a young fighter, mixed up with a crooked promoter, who sees the error of his ways and throws in with a crusading journalist to clean up the sport.† Dmytryk shot a screen test with Ryan as the fighter, then decided to give the role to Richard Denning; as a consolation prize he cast Ryan as Denning’s opponent in the climactic bout. They began shooting the fight in mid-December and finished in seven days; given nothing but a soundstage and three hundred extras, Dmytryk managed to evoke an entire stadium by dimming the lights on the audience, as at a real fight, and using bee smokers to create a cigarette haze over the crowd. Dmytryk was impressed with Ryan in the ring: “He was 6′ 4″, weighed 198 pounds, boxed beautifully, and hit like a mule. He tapped Denning in the ribs during their fight, and Dick made three trips to the hospital for X-rays. To this day he insists his ribs were broken, though the pictures showed nary a crack.”21

With the role came a contract as a stock player at Paramount for $125 a week, and the chance to experience a moviemaking operation from the inside. As Ryan sat with photographers and makeup artists and casting people, his physical attributes were evaluated with cold precision. At thirty years old, he was a seriously handsome Black Irishman, lean and muscular, with a strong jaw and a warm, brilliant smile. Yet his forehead was already lined from years of hard labor, and his brown, crinkly eyes were rather small in his face; if he narrowed them even slightly, they took on a beady, menacing quality. His height was impressive but hardly ideal for someone trying to get a leg up in supporting roles. “The men stars wouldn’t have me in a picture with them,” he recalled. “I towered over so many of them.”22

Paramount threw him bit roles: one morning in January 1940 he shot a scene for Queen of the Mob, based on the story of Kate “Ma” Barker and the Barker-Karpis gang, and a month later he put in two days playing an ambulance driver, barely glimpsed on-screen, in the Bob Hope comedy The Ghost Breakers. From mid-March to early May he was a Canadian mountie in Cecil B. DeMille’s North West Mounted Police, starring Gary Cooper and Madeleine Carroll, and that same month he played a train passenger in the nondescript western The Texas Rangers Ride Again. Ryan was disappointed but not exactly surprised when Paramount cut him loose after six months. Rather than hanging around Hollywood, waiting for something to happen, he and Jessica resolved to look for stage work in New York.

Back in Manhattan, the couple scraped by on Jessica’s modeling gigs and whatever Ryan could find. A year after Hitler’s invasion of Poland had ignited the war in Europe, President Roosevelt succeeded in passing the Selective Service Act, which established the country’s first peacetime draft and required the registration of all men from twenty-one to thirty-five years old. As a married man, Ryan was unlikely to be drafted soon or at all, but Jessica was horrified by the idea of him going to war. Ryan “believed that people should fight their own fights,” their son, Cheyney, later wrote. “Hence, if you believed in a war, you should be ready to fight it yourself.” Yet Jessica had been raised to believe that all war was immoral. “For her, war was not a story of people fighting their own fights. It was one of the privileged sending others to pay the costs while they reaped the benefits and attacked the patriotism of others along the way.”23

By June 1941 they had hired on at the Millpond Playhouse, a summer stock theater in Roslyn, Long Island. The productions tended toward mystery and comedy; the company, Ryan recalled, was “appalling, being mostly bad amateurs.”24 In The Barker he played a carnival barker and Jessica a hootchie cootchie dancer; two weeks later they costarred again in something called Petticoat Fever. Millpond staged a mystery play Jessica had written, The Dark Corner, and in the comedy Angel Child, Ryan costarred with twenty-two-year-old Cameron Mitchell. The highlight of the season was William Saroyan’s philosophical barroom comedy The Time of Your Life, starring Ryan as the rich drunk, Joe, who encourages the other barflies to live life to the fullest.

The Ryans bailed out soon afterward, landing first at the Robin Hood Theater in Arden, Delaware, and then at the Cape Playhouse in Dennis, Massachusetts, where Ryan won a romantic role opposite the celebrated Luise Rainer in J. M. Barrie’s comic fantasy A Kiss for Cinderella. Set in London during World War I, the class-conscious fantasy told the story of a poor cleaning woman, played by Rainer, who dreams that she is Cinderella and the neighborhood constable, to be played by Ryan, is Prince Charming. This guy is going to be a big star, thought Robert Wallsten, a fellow cast member, as he watched Ryan rehearse. “I had no idea about his dramatic ability, and playing this Irish bobby was not a very serious role. But he had a corner on that Irish charm, and there was that magic grin…. It was the smile that was so warm and engulfing, and so endearing.”25 Wallsten would become one of the Ryans’ oldest friends.

From Dennis the production moved to the Maplewood Theatre in Maplewood, New Jersey, where Ryan caught an extraordinary break. Rainer had been married to Clifford Odets, a founder of the Group Theatre and one of the most daring American playwrights of the day (Waiting for Lefty, Awake and Sing!); with the recent demise of the Group, Odets had sold his play Clash by Night to showbiz impresario Billy Rose, who was mounting a Broadway production with Lee Strasberg, another Group founder, as director. The play dealt with an unhappy working-class couple on Staten Island, but in a larger sense it considered the restive political mood in America as the war in Europe raged on. Tallulah Bankhead, hailed for her recent performance in Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes, had signed to play the bored and frustrated wife; Lee J. Cobb, among the Group’s most gifted actors, was cast as her dense but devoted husband; and Joseph Schildkraut, a longtime stage and screen veteran who had won an Oscar playing Alfred Dreyfus in The Life of Émile Zola, was the husband’s cynical friend, who moves in on the wife. For the minor role of Joe Doyle, a young neighbor with romantic problems of his own, Rainer urged Odets to consider her handsome young lead in A Kiss for Cinderella.

Rose took Bankhead out to Maplewood to see the show, and she liked Ryan. Soon after A Kiss for Cinderella closed on September 23, 1941, he was rehearsing Clash by Night in New York City. One can only imagine his excitement: four months earlier he had been slugging it out at the Millpond Playhouse, and now he would be making his Broadway debut in a cutting-edge social drama, alongside some of the most respected talents in the American theater. He had seen Bankhead in The Little Foxes and thought her an extraordinary actress.26 A world-class diva, she could be witheringly cruel to colleagues, but she took a shine to him during rehearsals. When he introduced her to Jessica, who had been modeling to help meet the rent, Bankhead quipped, “If I was fifteen years younger I’d take him away from you.”27 The Ryans laughed, though Jessica couldn’t have been too pleased. She would spend the next thirty years meeting women who were less frank but similarly inclined.

“Tallulah was a stereotype of what the public thinks star actresses are like: they really aren’t except in her case,” Ryan would remember. “She liked some kind of excitement going on and didn’t much care where it came from.” At the same time Bankhead was a consummate professional, the first to arrive and the last to leave, and always with her part down cold. She might challenge Strasberg or Odets in rehearsal, yet in performance she could be remarkably generous toward other players. “She was a great experience,” Ryan would conclude, “and she came along at a most important time in my life.”28

Unfortunately, the production quickly degenerated into a snake pit of professional rivalries and personal grudges, from which Ryan was lucky enough to be excepted. Bankhead despised Billy Rose, a diminutive casting-couch type whose theatrical résumé consisted mainly of brassy revues. “He approached the Odets play as if he were putting on a rodeo,” she later wrote.29 An elegant presence onstage, Bankhead had taken the role of the drab housewife as a dramatic stretch, but when the play began its out-of-town tryouts in Detroit, critics decided she had been miscast, favoring Lee Cobb’s performance as the husband. “That was when the shit hit the fan,” Ryan remembered.30 Bankhead and Katherine Locke, who played Ryan’s girlfriend, soon fell out, united by nothing except their dislike of Schildkraut, whom Locke later accused of putting the moves on her.31

Though some of these conflicts sprang from ego or personal enmity, the production was built on an artistic fault line that would become more apparent in years to come: on one side were the more traditionally trained actors such as Ryan, Bankhead, and Schildkraut, and on the other were proponents of the Method such as Cobb and Strasberg, the latter of whom would institutionalize the techniques of tapping into one’s own emotional experience when he founded the Actors Studio six years later. Method acting could be fresh, genuine, even explosive, but it could also be unpredictable and inconsistent from night to night. Cobb, the most ardent Method actor among the cast, often seemed to be working through his role onstage, and for someone such as Bankhead, playing against him was one curveball after another. Ryan sympathized with her, and later in his career, colleagues would note his annoyance and even anger over onstage surprises.

From Detroit, Clash by Night moved on to Baltimore, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia, where Bankhead came down with pneumonia and the show was shut down (as the star, she had no understudy). While the cast and crew cooled their heels in New York, waiting for her to recover, Ryan scored an interview for the lead role in a Hollywood prestige picture to begin shooting the next year. Pare Lorentz — whose acclaimed documentary shorts The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936) and The River (1938) had won him a brief but controversial tenure as director of the US Film Office — had signed with RKO Radio Pictures to direct a dramatic feature about a war veteran trying to make ends meet during the Depression, to be titled Name, Age and Occupation. For six months he had been crisscrossing the country in search of an actor skillful enough to play the role but credible enough to function in the semidocumentary format Lorentz envisioned. Finally, he turned to his friend John Houseman, an erudite British producer who had collaborated famously with Orson Welles.

Working for the Federal Theatre Project, Houseman and Welles had staged the “voodoo” Macbeth (1935), which transplanted the Shakespeare play to a Caribbean island, and the proletarian musical The Cradle Will Rock (1937), which proved too hot for the government and inspired them to launch the independent Mercury Theatre. Houseman and Welles had gone on to create the CBS radio broadcast The War of the Worlds, which had terrified the nation with its too-convincing account of a martian invasion, and the RKO drama Citizen Kane (1941), whose critical acclaim had now emboldened the studio to bankroll Lorentz’s ambitious project. Houseman arranged for Lorentz and himself to spend a week interviewing actors in a Manhattan hotel suite. When Ryan arrived to read for the part, his acting must have impressed them, but what really won over Lorentz was Ryan’s endless litany of soul-crushing jobs in the depths of the Depression. Here was a man who not only could play the part but already had lived it.

In the 1972 memoir Run-Through, Houseman would remember traveling by train with Lorentz through western Kansas and hearing on the radio in the club car that the Imperial Japanese Navy had attacked the US air base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, killing and wounding thousands of Americans. The next day the United States and United Kingdom declared war on Japan. Three weeks later, Clash by Night opened on Broadway at the Belasco Theatre, its take on the national mood decisively outpaced by world events. Reviews were scathing, though the players got good notices for their work, Ryan included; most critics went to town on Odets, citing a lack of passion and fresh characterization. The play closed on February 7, 1942, after only forty-nine performances, but not before Ryan was seen by such luminaries as Greta Garbo, Judith Anderson, Ruth Gordon, and Thornton Wilder.

“Ryan’s was a small part,” remembered Tony Randall, then a young actor starting out in New York, “but he was very, very good.”32 According to one news story, Ryan was “showered” with offers from New York producers, including one from the Theater Guild to appear in a new play with Katharine Hepburn.33 The attention went to his head. He would remember “swaggering” into Bankhead’s dressing room one night and “demanding to know how long it was going to take before I was a really great actor. I expected her to say a year or so. But instead she said very quietly, ‘In 15 or 20 years you may be a good actor, Bob — if you’re lucky.’”34

*For more on this fascinating topic, see Martha Hope Bacon, Mothers of Feminism: The Story of Quaker Women in America (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1986).

†The picture was loosely based on the story of Arch Ward, a Chicago Tribune sports editor who had founded the tournament in the 1920s.