Читать книгу The Lives of Robert Ryan - J.R. Jones - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеthree

Bombs Away

Soon after the Odets play breathed its last, Ryan found himself in Tennessee shooting locations for Name, Age and Occupation with director Pare Lorentz and actress Frances Dee. The movie’s story dated back to a novel Lorentz had begun in 1931: an eighteen-year-old boy from North Carolina fights overseas in the Great War but finds nothing waiting for him back home except a series of dehumanizing farm and factory jobs. As Houseman explained, the movie would explore “the condition of the US industrial worker with special emphasis on the economic and emotional effects of the production line.”1

Lorentz already had tried mixing actors with real people, to less than stellar effect, in his documentary The Fight for Life (1940), about the Chicago Maternity Center and infant mortality in the slums. But George Schaefer, president of Radio-Keith-Orpheum, was prepared to take a gamble on the director; before Ryan even reported for work, Lorentz and cinematographer Floyd Crosby had spent twenty days shooting industrial operations at Ford’s River Rouge Plant and a US Army facility. Location shooting continued through the spring, and in June the company arrived in Los Angeles to spend four weeks shooting interiors on the Pathé lot in Culver City.

That same month, fed up with Schaefer’s artistic pretensions and dismal bottom line, the RKO board replaced him with N. Peter Rathvon and installed Ned Depinet as president of the movie division, RKO Radio Pictures. Charles Koerner, the new, commercial-minded head of production, immediately targeted two runaway films: It’s All True, which Orson Welles had been shooting in Brazil since early that year, and Name, Age and Occupation. Lorentz, observed director Edward Dmytryk, was “a fine critic, a top maker of documentaries, but completely lost in straight drama. After 90 days of shooting, he was 87 days behind schedule.”2

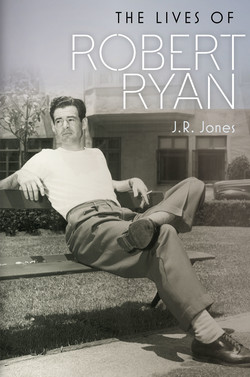

Ryan on location with director Pare Lorentz for the ill-fated Name, Age and Occupation. Their RKO colleague Edward Dmytryk called Lorentz “a fine critic, a top maker of documentaries, but completely lost in straight drama. After 90 days of shooting, he was 87 days behind schedule.” Robert Ryan Family

In late June, RKO halted production of Name, Age and Occupation and asked Lorentz for a financial accounting.3 He must have seen the writing on the wall when Koerner announced his production plans for 1942–43: $12 million was budgeted for only forty-five features, and in contrast to the literary projects favored by his predecessor, RKO would be aiming for good, solid box office by making patriotic movies for the home front. Name, Age and Occupation, with its Depression setting and heavy themes, hardly filled that bill, and after screening rushes, RKO executives killed the project.

They liked Ryan, however, and signed him to a $600-a-week contract; under Schaefer the movie division had developed a shortage of leading men, exacerbated now by the many actors enlisting in the armed forces. “Without the talent shortage I would very likely have still been grubbing around New York for 40 a week jobs where I more or less belonged at my stage of the game,” Ryan confessed in a letter to a friend.4 He and Jessica moved their belongings back to Los Angeles and rented a house in Silverlake, which they shared with Ryan’s fifty-nine-year-old mother, Mabel. By October he had his first assignment from RKO, a picture about the US Army Air Forces called Bombardier. With this new job, the couple decided the time had come for children. Before long Jessica was pregnant, but she miscarried early the next year, another sad bond for two partners who had each lost a sibling in childhood.

With Clash by Night and now Name, Age and Occupation, Ryan had been involved with two prestigious dramas that crashed and burned yet elevated him professionally. Two years after his pink slip from Paramount, he was back in Hollywood earning nearly five times as much from RKO. Boom times had returned to Hollywood with the US military mobilization against Germany and Japan: as defense plants hummed in the nation’s industrial centers, workers with good wages packed the movie palaces in search of solace, inspiration, or just relief from their worries. The studios cooperated eagerly with the Office of War Information to rally moviegoers to the war effort, and of the seven features Ryan would make over the next sixteen months, every one addressed the war in some way.

Even as he cranked out these patriotic pictures, Ryan waited for his own draft notice to arrive. After Pearl Harbor the draft age had been widened to include all men from twenty to forty-four years old; he was thirty-two, but Congress and public opinion favored drafting single men over husbands and fathers. In February 1942 the director of selective service, Lewis B. Hershey, had ruled that movies were “an activity essential in certain instances to the national health, and in other instances to war production” and had granted deferments for essential “actors, directors, writers, producers, camera men, sound engineers and other technicians.”5 The outcry in Congress and around the country was immediate, and within forty-eight hours the board of the Screen Actors Guild had voted to oppose the order, arguing that “actors and everyone else in the motion picture industry should be subject to the same rules for the draft as the rest of the country.”6 Hershey soon reversed the policy, but California draft boards were generally cooperative toward the big studios.

Bombardier had been in development for two years already and took as its inspiration not a play or novel but a piece of military hardware, the top secret Norden bombsight, which used a mechanical computer to calculate precision bombing at high altitudes. Pat O’Brien starred as an air force major preaching the virtues of the new contraption, and Randolph Scott was his friendly antagonist, a captain who favors traditional dive-bombing attacks. Ryan was cast as a jaunty young cadet at the new aerial bombardment training school (one scene has him reciting for O’Brien a pledge similar to that taken by real-life bombardiers, that he will “protect the secrecy of the American bombsight, if need be with my life itself,” as strings swell and O’Brien looks on in misty-eyed sanctification).

Most of the movie was shot on Kirtland Army Air Base in New Mexico, whose bombardier training program was the model for the one in the movie. RKO vetted the script with the Office of War Information in exchange for access to planes and other resources; one fascinating scene in Bombardier shows Ryan’s cadet practicing atop a bomb trainer, a twelve-foot frame on wheels that simulates bombing trajectories as it rolls toward a small, motorized metal box representing the target. In return the army got a wholesome, rousing picture that reasoned away any qualms one might have had about raining death from above. One cadet is torn by letters from his mother, who belongs to a peace organization and fears for his soul. “Peace isn’t as cheap a bargain, Paul, as the price those people put on it,” his commander explains. “Those people lock themselves up in a dream world. You see, there are millions of other mothers that are looking to you.”

Ryan put in five weeks on the shoot, though the cast was large and he didn’t get much time in the foreground. At one point he bursts into a funeral service for a young trainee to announce in close-up, “The Japs have bombed Pearl Harbor!” During the climax, as Scott and Ryan fly a nighttime scouting mission over Japan in advance of the squadron, their plane is hit; instead of bailing out with the others, Ryan stays behind to dismantle the bombsight with a pistol (actual military protocol) and dies in a giant fireball when the plane crashes. The absurd ending has Scott, captured behind enemy lines, escaping from the Japanese to drive a flaming truck around the munitions plant for the benefit of O’Brien’s squadron above. With its fiery payoff, Bombardier validated Charles Koerner’s new production strategy when it opened the following spring: budgeted at $907,000, it grossed $2.1 million.

More so than the bit parts at Paramount, Ryan’s roles at RKO gave him a chance to learn the craft of screen acting, which favored subtlety of expression and demanded incredible mental focus. “On the stage you can coast along,” he explained to a journalist years later.

You don’t have to concentrate so intensely on small details as you do in a movie.… Let’s say in this scene, you’re talking to me and I’m supposed to be taking a sip from this cup while I listen to you…. on the stage, it doesn’t make any difference when the cup goes back into the saucer because nobody can hear it. But in a movie scene, while I’m listening to your lines and thinking of the line I have to say next, I must also remember to time the return of the cup to the saucer so that it won’t get there until after you finish the last word from your speech, and not a split-second before you finish. If the cup hits the saucer while you’re still talking, the clack it makes on the soundtrack will clash with your last words and ruin the scene. A half-hour later we have to do the same scene over again for a close-up or from a different camera angle and it has to be done exactly the same as we did it before.7

But even more than acting experience, Ryan took away from Bombardier a long, warm friendship with Pat O’Brien, who liked the young man’s professionalism and soon began lobbying to have him in his pictures. They shared some striking similarities, including a birthday (O’Brien was exactly ten years older), a Catholic upbringing in the Midwest (he had attended Marquette Academy and Marquette University in Milwaukee), and a love of Chicago (he had met his wife, Eloise, while appearing in a show at the Selwyn Theater in 1927). O’Brien had been summoned from the New York stage to Hollywood by Howard Hughes, who cast him as Hildy Johnson in the movie version of Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s The Front Page (1931). O’Brien soon moved to Warner Bros. and became a professional Irishman, costarring no fewer than eight times with his pal James Cagney, before memorably embodying the title Norwegian in Knute Rockne, All American (1940).

That hit allowed him to end a long, frustrating relationship with Warners and eventually sign with RKO. “I loved that RKO lot, as did most who worked there,” O’Brien later wrote. “It exuded more friendliness and warm camaraderie than any studio in which I ever worked.”8 In addition to Cagney, O’Brien was tight with Frank McHugh, a pudgy comic actor who had been with them at Warners, and Spencer Tracy, an old classmate at Marquette Academy. Ryan got to meet them all, though he was never social enough to be considered part of this “Irish mafia.” When Ryan asked O’Brien if his natural reticence would hurt him in the movie business, O’Brien pointed to Cagney, who was equally private but remained one of Hollywood’s biggest stars. “That was all I needed to know,” Ryan recalled. “I became a Cagney.”9

Ryan’s next assignment brought him into close quarters with another big talent. The Sky’s the Limit, which began shooting in February 1943, starred Fred Astaire as a heroic Flying Tiger who goes AWOL during a publicity tour of the United States and falls for news photographer Joan Leslie; chasing after him are his two pilot buddies, played by Ryan and Richard Davies. Ryan’s character, Reggie Felton, is a snide comedian: riding in a parade, he prepares to poke Davies in the eyes Three Stooges–style but then remembers where he is and flashes the crowd a “V for Victory” sign. He spends most of his screen time needling Astaire, and in one memorable scene, set in an army canteen, blackmails him into doing a “swami dance” atop their table. Choreographed by Astaire, the dance took several days to film, during which Ryan sat in a chair looking up at the great performer. Ryan even scored some waltz lessons from Astaire when the scene called for him to share a dance with Leslie.

Behind the Rising Sun, which began shooting in late April, was the darkest and most interesting of Ryan’s wartime releases, an anti-Japanese propaganda picture of some journalistic substance but even more racial hysteria. Its source material was a 1941 book by James R. Young, an American journalist who had spent thirteen years working for the influential Japan Advertiser before his reporting from occupied China, published in a variety of Japanese papers, got him arrested in Tokyo and held by police for sixty-one days. Behind the Rising Sun offered a variety of insights into Japanese culture and a ringing indictment of the Imperial Army’s misadventure on the continent. Young’s sympathy and affection for the people of Japan was evident throughout, yet Doubleday Doran had packaged the book with a cover drawing of a slit-eyed, hideously grinning man, a fan in one hand and a revolver in the other.

After directing Ryan in Golden Gloves over at Paramount, Eddie Dmytryk had landed at RKO and, with screenwriter Emmet Lavery, had assembled an anti-German propaganda piece called Hitler’s Children, about the Hitler Youth movement. For Behind the Rising Sun the two men banged out a script that bore little resemblance to the book, but incorporated various incendiary news stories from prewar Japan. “On a not very original plot, we strung ten or twelve incidents calculated to increase the flow of patriotic juices,” Dmytryk recalled.10 One of them involved a fighting match between an American boxer and a Japanese sumo wrestler, and Dmytryk had just the guy to play the boxer.

The not-very-original plot involved a Tokyo businessman (J. Carrol Naish), whose son Taro (Tom Neal) returns from the United States with an engineering degree from Cornell, falls for a pretty secretary (Margo), and clashes with his father over her. Nearly all the Japanese characters were played by American actors in eye makeup; Neal is particularly unconvincing, bounding down a ship’s gangplank to announce in pure Americanese, “Gee, Dad, it’s good to see you!” Later Taro serves with the Imperial Army in an occupied province of North China, where he hardens himself against atrocity. Confronted by an American reporter (Gloria Holden) in his office, he watches from a window as soldiers throw a child into the air and — Dmytryk implies with a jump cut — catch it on a bayonet. “They’re not my men,” Taro replies. “It’s not my responsibility.”

Billed fourth in the credits, Ryan played Lefty O’Doyle, a bushy-headed American baseball coach in Tokyo, and of the few incidents or observations from Young’s book that found their way into the movie, many involved him. When Taro shows up at a game with his sweetheart, O’Doyle points out the flag display interrupting the game on the field. “Can you beat it?” he asks them. “Telling them that baseball isn’t just baseball anymore? They mustn’t come here to enjoy it just as a sport. They must come here to enjoy it as a military exercise.” Another scene, lifted directly from the book, takes place during a late-night poker game at a geisha house where O’Doyle, who’s had a few drinks too many, loses his temper over a mewling cat and fires his pistol into the darkness, scaring it away. Almost immediately a trio of police appear at the door to grill and browbeat him and his companions about the fired gun and the “arreged cat.”

The big fight scene, which began shooting one Saturday afternoon in mid-May and continued the following Monday, would wind up the movie’s oddest and best-remembered moment. O’Doyle is called upon to defend the honor of an American engineering executive who has clashed with Taro; defending Taro’s honor is a towering sumo wrestler, played — in eye makeup — by Austrian-American wrestling champ Mike Mazurki.* At thirty-six, Mazurki stood an inch taller than Ryan and was built like a brick wall. The ensuing fight is less a match than a melee, O’Doyle throwing roundhouse punches as the wrestler kicks, chops, and grapples with him. In the end the boxer triumphs, yet even this wacky contest has a sharp edge: for dishonoring Japan, the wrestler is later executed.

Ryan triumphs as the American boxer pitted against Japanese sumo wrestler Mike Mazurki in RKO’s propaganda item Behind the Rising Sun (1943). When Ryan joined the Marine Corps, his reputation from the picture preceded him. Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research

THREE DAYS BEFORE MIXING IT UP with Mazurki, Ryan was inducted into the US Army. His draft notice finally had arrived, and RKO had arranged for a deferment so he could finish Behind the Rising Sun and The Iron Major, which were shooting simultaneously. The latter film was RKO’s attempt to score with Pat O’Brien playing another legendary college football coach — in this case Frank Cavanaugh, whose long career was interrupted only by his meritorious service in France. O’Brien had lobbied for Ryan to play Timothy Donovan, a football hero under Cavanaugh who later became a priest and served alongside him as an army chaplain. Ryan ages unpersuasively from his early twenties to his sixties, with the usual graying temples, and brings the story to a close with a mawkish prayer promising his late friend Cavanaugh that the fight for freedom continues: “We thank you, Cav, and we salute you. God rest your gallant soul.”

Another deferment was granted so Ryan could appear in the low-budget Gangway for Tomorrow, an inspirational tale for the home front about five random folks riding in a carpool to their jobs at a defense plant. As they travel, flashbacks reveal stories from their past; Margo had a pretty good one, playing a French cabaret singer and resistance member who escapes from the Nazis, but Ryan’s was a hokey number about an auto racer who wipes out in the Indianapolis 500 and has to stay home while his two buddies join the Army Air Corps. Originally titled “An American Story,” the picture wore its Office of War Information credentials on its sleeve: in the final moments the workers arrive at the plant, lock arms, and head through the gates to the strains of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

By summer Bombardier had opened to tremendous box office, and preview screenings of The Sky’s the Limit and Behind the Rising Sun had brought Ryan overwhelmingly positive response cards from patrons. David Hempstead, producer of The Sky’s the Limit, was about to start an A picture with Ginger Rogers called Tender Comrade, and he urged her to consider Ryan for the male lead. Written by the talented Dalton Trumbo, Tender Comrade told the story of four women working in a Los Angeles airplane factory who decide to rent a house together; interspersed with this were flashbacks focusing on Rogers and her man, who’s preparing to go to war. For an unknown actor this would be quite an assignment — seventeen solitary love scenes with one of Hollywood’s biggest stars.

Rogers had caught a preview of The Sky’s the Limit at the invitation of her old dance partner Fred Astaire; she thought Ryan was too tall and too mean looking, but she agreed to let him read for the part. When Ryan showed up to audition, he found about a hundred other actors waiting. Yet as he and Rogers talked and played scenes together, she slipped Hempstead a note: I think this is the guy. Later, when Hempstead offered Ryan the job, he gave him the slip of paper, which Ryan kept to the end of his life.

Tender Comrade would be Eddie Dmytryk’s first A picture, and he spent a full month, from mid-August to mid-September, directing Ryan’s love scenes with Rogers. The first of them neatly demonstrated Ryan’s skill at expressing character through action: Jo (Rogers), alone one night in her studio apartment, hears a knock at her door and is overjoyed to discover it’s her husband, Chris (Ryan), home on furlough; as he steps into the room, he swings his overnight bag into the air and sends it sailing across the room onto her bed. Ryan plays straight man to Rogers in the forced comic scenes detailing their early relationship, but he comes into his own as the couple begin wrestling with the fact that he wants to enlist. “I’ve never felt so at-home in a role in my life,” Ryan told Photoplay. “Y’know, a lot of these scenes are retakes of things that have happened between Jessica and myself.”11

Ryan and Pat O’Brien in Marine Raiders. O’Brien mentored the younger actor at RKO, but they wound up on opposite sides when the House Un-American Activities Committee came to Hollywood. Franklin Jarlett Collection

Trumbo was one of Hollywood’s more politically outspoken writers — he had participated in the founding of the Screen Writers Guild, the movie industry’s bitterest labor battle of the mid-1930s — and with Tender Comrade he added a provocative subtext to the standard women’s picture. Jo (Rogers) can barely contain her heartache after Chris ships out; but while he’s gone, she comes up with the idea of pooling her rent money with three fellow riveters. They agree to a majority vote on all matters, and Jo proposes that they share their resources further: “Now the four of us here have two cars, two sets of tires wearing out. We could sell one car and use the other on a share-and-share alike basis.” Rogers, a determined anticommunist, had balked at Trumbo’s original line: “Share and share alike — that’s American.”

Ryan was scheduled to report for duty on October 20, but as the date approached, RKO offered him yet another script. Pat O’Brien wanted Ryan to costar with him in a war picture called Marine Raiders, about the Marines’ new amphibious commando units. The script was lousy, with tedious love scenes and chest-thumping heroics. In one jungle scene Ryan’s impetuous captain finds a fellow marine who has been killed and desecrated by the Japanese; enraged, he goes charging into the enemy’s position spraying machine gun fire.

To play something like this at Camp Pendleton in San Diego County, where Marine Raiders would be shot as less fortunate men actually shipped out for the Pacific, must have filled Ryan with the sort of manly shame he had felt as a male model. Stars the stature of James Stewart and Robert Montgomery had enlisted and taken combat assignments; even Pat O’Brien put himself in harm’s way entertaining troops in northern Africa and Southeast Asia. As part of the deal struck by RKO, Ryan asked to be discharged from the army so that he could enlist in the Marines, which would mean a greater chance of seeing combat. The Marines, in turn, would give him a deferment until January 1, 1944, so that he could make the picture.

Marine Raiders didn’t wrap until late January, however, and by that time the Marines had granted Ryan a second deferment through February 15. Shortly before the picture was completed, the commanding general at Camp Elliott in San Diego wrote to Marine Corps Commandant Alexander Vandergrift to request a third deferment through April 15, so that Ryan could appear opposite Rosalind Russell in Sister Kenny, a biopic of the Australian nurse who had developed a radical new treatment for polio. Vandergrift would have none of this, and Ryan was ordered to report for duty on the fifteenth as previously agreed. RKO was offering him a “duration contract,” which meant that he would be welcomed back to the studio upon his discharge from the service. Behind the Rising Sun had been released in August and, partly on the strength of Ryan’s much-talked-about fight scene, turned a jaw-dropping $1.5 million profit.

In a movie magazine piece that appeared under her byline, Jessica recalled “the dreary building in downtown Los Angeles” where she dropped Robert off for his Marine Corps induction. “It was that ungodly hour of the morning, at which time all good men seem to have to go to the aid of their country.”12 They said their good-byes, she drove away weeping, and Ryan finally joined the war.

*Though still working his way up in bit roles, Mazurki would play heavies in movies and TV for another fifty years, most memorably in Murder, My Sweet (1944).