Читать книгу The Lives of Robert Ryan - J.R. Jones - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеfour

You Know the Kind

If Ryan had any hope of remaining unnoticed in the ranks, they were diminished when he learned from a fellow recruit at the LA induction center that a letter from the Marine Corps — which Ryan had never gotten — listed toiletries and other items they should bring with them. A private on duty offered to pick up some things for him, and Ryan got off the bus in San Diego carrying his belongings in a brown paper bag. A Marine Corps photographer was there to meet him, snapping pictures as he turned in his travel orders, got fitted for fatigues, sat for a regulation army haircut, went through a classification interview, and picked up his gear from the quartermaster’s depot. After that he was on his own and wondering how he would be received. When he had been at the base earlier, shooting Marine Raiders, an officer had told him that movie boys were liable to get roughed up in the Corps, but Ryan didn’t have any trouble. He mentioned this to a bunkmate; the man replied, “Most of these guys saw you bat that Jap around in Behind the Rising Sun.”1

Basic training commenced at Camp Pendleton, about an hour north of the San Diego base. Established as a Spanish mission in 1769 and built up through land grants into the vast Rancho Santa Margarita, the property had been purchased in 1942 by the US government, which was converting it into the nation’s largest Marine Corps base. It was enormous — about two hundred square miles, with eighteen miles of shoreline for amphibious training. According to Pendleton historians Robert Witty and Neil Morgan, the terrain “stretches eastward across twelve miles of rolling hills, broad valleys, swampy stream beds, and steep-sided canyons, rising on its northeast perimeter to a height of 2,500 feet.”2 By the time Ryan arrived, Pendleton had sent two divisions into the war and was home to more than 86,000 people.

He and Jessica had resolved to keep a stiff upper lip in each other’s absence, but by the fourth week Ryan had written asking her to visit him that Sunday, and she endured the four-hour bus ride to meet with him at the reception center. They went outside, and he spread his poncho over the grass so they could sit and talk. He had learned how to use an automatic rifle, Thompson submachine gun, mortar, bayonet, and hand grenade. The infiltration course, in Wire Mountain Canyon, forced recruits to crawl through three trenches and penetrate a single and then a double apron of barbed wire while dynamite charges went off all around them and live rounds were fired over their heads. The obstacle course, built over a cactus patch, included a 125-foot wooden tunnel, a house whose only exit was through the roof, and a 100-foot cable bridge. He was mastering more mundane skills as well — how to mend his clothes, for instance — and drilling with his platoon. As the tallest marine, he was named honor man and placed in the front rank to set the pace; he took direction well, of course, and had to admit that the theatricality of it appealed to him.

Following a ten-day furlough in April, Ryan got his first assignment: effective immediately, he would be a “recreation assistant” at Pendleton. This was good news for Jessica, who wanted him out of harm’s way and far from the trigger of a gun, but not for him. The whole idea of enlisting in the Marines was to erase the stigma of all those deferments; now he would be running a sixteen-millimeter projector and directing amateur plays. After fifteen weeks of this, during which time the D-Day landing commenced, he was transferred to the San Diego base, where he continued to thread a projector and also performed on Halls of Montezuma, a weekly radio show broadcast coast to coast. Once Jessica realized he was unlikely to see action, she decided to leave Mabel on her own in Silverlake and moved to San Diego, where she occupied a “tiny box of a house on the pier at Pacific Beach.”3

By this time Jessica had stopped acting entirely. Back when they were with Reinhardt, she had been considered the better actor, but over the years she had watched Robert work and grow, and she was proud of his success. She had been at it for ten years now, and once Robert had started pulling down $600 a week at RKO, she decided she had had enough. She hated the stage fright and the tedium and the itinerant lifestyle. Instead she would turn to her second love, writing. In addition to the first-person piece about Robert’s induction, which would appear in the October 1944 issue of Movieland, she began placing stories in fan magazines such as Photoplay and Motion Picture and women’s magazines such as Coronet and Mademoiselle. Her immediate success would bring a weird parity to the marriage, since Robert had started out writing and, frustrated, turned to acting.

Serving on the sidelines must have gotten to Ryan, because on August 25 — the day Paris was liberated — he applied for a commission as a second lieutenant to serve on an aviation ground crew. “I feel that my background would qualify me for any branch of ground duty not requiring technical knowledge or expertise,” he wrote on his application.4 A complete physical found him fit for overseas duty, and his commanding officer wrote him no fewer than three letters of recommendation. He waited the rest of the year for an answer. The Marine Corps was hardly generous with promotions, and he had no way of knowing whether the scuttlebutt about his deferments would hurt his chances, or what RKO might be doing behind the scenes to protect its investment.

In January 1945, as the Battle of the Bulge raged, Ryan was assigned to the Fortieth replacement draft; he would be shipping out as an infantryman, a development he would later describe to a friend as “swell.”5 His application for a commission was turned down a week later. Ryan would be leaving for the Pacific in late February, which was alarming news to his wife and mother. But things didn’t work out that way: as he would tell his Dartmouth class newsletter, “I was yanked out of the infantry with the proverbial foot on the gangplank and put to instructing troops in bayonet, judo, boxing and such at Camp Pendleton.”6 Now classified as a combat conditioner, Ryan would spend his days training men for battle; in May he was promoted to private first class, and in August he was reclassified again, as a combat swimming instructor.

Thousands of Americans spent the war this way — not quite at home, not quite at battle. “Theirs is the task of the damned,” wrote Richard Brooks in a prefatory note to his novel The Brick Foxhole. “These men see others trained and shipped off to ports of embarkation, but they themselves are always left behind. They brood over it, and in the end they become disappointed, introverted, and embittered.”7 Ryan read the book with great interest when it was published in May 1945; the author was actually stationed at Pendleton, and according to scuttlebutt, the publication had brought him a court-martial. At the center of The Brick Foxhole was an ugly sequence in which soldiers at liberty in Washington, DC, go home with a homosexual man for some late-night drinking and wind up beating him to death. Ryan was struck immediately by the book’s frank depiction of the bilious prejudice on open display at Pendleton.

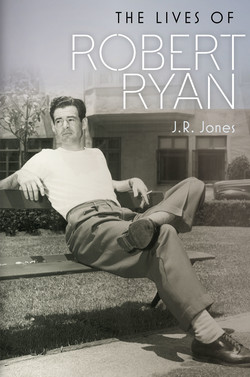

Robert and Jessica (circa 1944). While he drilled recruits at Camp Pendleton, she struck out on her own as a magazine writer and novelist. Robert Ryan Family

Of particular fascination was the character of Montgomery Crawford, the bullying sergeant who drags the other men into this murderous episode. Monty has served as a beat cop in Chicago and likes people to know he’s killed a Jew and two black men in the line of duty. He “always shot niggers in the belly because then they didn’t die right away and they squirmed like hell.” Ryan had known guys like this before — cruel, jingoistic, worshipful of authority. Monty “shook hands with too firm a grip and he would openly cry when the post band played ‘God Bless America.’”8

Ryan tracked Brooks down to tender his compliments, and the two met in the library at Camp Pendleton. Brooks was tall and athletic — for a while he had considered a career as a pro baseball player — and favored a pipe that belied his short temper. Born to Russian Jewish parents in Philadelphia, he had grown up in poverty and gotten his start as a writer during the Depression by riding the rails and reporting on his experiences for local newspapers. From there he had moved into radio drama in New York and, in a weird coincidence, cofounded and then quit the dreaded Millpond Playhouse the summer before the Ryans performed there. Out on the West Coast Brooks found work writing for NBC Radio in Los Angeles, and as a screenwriter at Universal he knocked out a couple of jungle pictures for Maria Montez before enlisting in the Marines. Rumors of a court-martial over The Brick Foxhole were true, though the Marines, realizing that more publicity would only enlarge the book’s audience, had ultimately dropped the case.

Brooks undoubtedly knew Ryan from his good-guy roles at RKO, and to his surprise the actor told him that, if The Brick Foxhole were ever filmed, he wanted to play Monty. Anyone could see the physical resemblance — Brooks had described Monty as “more than six feet tall” with “a pair of small, bright eyes”9 — but why would a lead player want a role like this? “I know that son of a bitch,” Ryan explained. “No one knows him better than I do.”10

In fact, Ryan’s experience as a combat conditioner — teaching men to kill and wondering if they would ever come back alive — was turning him against the military. When he wrote to his old Dartmouth pal Al Dickerson in early summer 1945, he took a dim view of his own contribution to the war. “I certainly haven’t made any ‘sacrifice,’” he admitted, “especially when you add the fact that I have sat on my ass stateside for 16 months while a lot of my buddies went on to Saipan and Iwo…. I will not bore you with the too well known complaints against the military. War is a stupid institution when it isn’t being sinful and tragic and catastrophic.”11 By the time he got out of the Marines he would come to share much of Jessica’s pacifist philosophy.

Meanwhile Jessica had come into her own as a writer. To Ryan’s surprise she announced one day that she had written a mystery novel and wanted him to read it. The Man Who Asked Why was a “literary mystery,” mindful of formula but written with intelligence and wit. Its eccentric sleuth, Gregory Sergievitch Pavlov, “looked like a retired clown”12 but was in fact an eccentric professor of languages, transparently based on the Ryans’ dear friend and acting teacher Vladimir Sokoloff. Ryan passed the manuscript along to someone he knew at Doubleday Doran (publisher of Behind the Rising Sun), and to his and Jessica’s delight the book was accepted for publication as part of Doubleday’s Crime Club imprint, scheduled to appear in November.

In August the war, and the very concept of war, attained new levels of sin, tragedy, and catastrophe when President Truman ordered the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The blast in Hiroshima on August 6 flattened nearly five square miles and killed seventy thousand people, with tens of thousands more to die from burns and radiation by the end of the year. Few in America could grasp the devastation, but one thing everyone understood was that now Japan would surrender. RKO wasted no time in reasserting its claim to Ryan’s services; the day after Nagasaki was bombed, the Marine Corps director of public information dispatched a letter to the commandant asking that Ryan be allowed to make a “marine rehabilitation picture” called They Dream of Home.* This request was denied, and ten days later Ryan was assigned to the Seventy-Ninth Replacement Draft. His feelings about shipping out may have been different this time, though, because Jessica had discovered that she was pregnant.

Two weeks after receiving his new assignment, Ryan reported to the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery complaining of neck and back pain. According to the doctor’s summary, Ryan said that he had wrenched his back in May 1939, while lifting a car to change a tire, and subsequently suffered periodic attacks that had sidelined him for two to four days, but that “he did not mention this condition on induction because he considered it of minor importance and he wished to get into the service.”13 Diagnosed with epiphysitis of the spine, he was pronounced unfit for service and recommended for discharge. By this time the Fourth Division had begun arriving home, and Pendleton was discharging 175 men daily. On October 30, 1945, Ryan won an honorable discharge and returned to civilian life, the prospect of fatherhood, and a steady job at RKO. The studio had already slotted him for a melodrama called Desirable Woman that would give him a chance to work with Joan Bennett and the great French director Jean Renoir.

Years later, press accounts would note simply that Ryan had enlisted in the Marines, which was true but hardly the whole story. His wife’s pacifism, his employer’s opportunism, and his own professional ambition had kept him out of uniform for nine months, but then he had served and sought a combat assignment. He would note with disdain how his friend John Wayne had avoided doing his duty, and his own stint in the Marines would become a much-valued credential as he became more vocal in his commitment to peace. When his teenage son, Cheyney, asked him why he had served, Ryan’s only response was, “What else was I gonna do?”14

SON OF THE GREAT PAINTER, Jean Renoir had directed some of the best French films of the 1930s — The Crime of Monsieur Lange, Grand Illusion, The Rules of the Game — before fleeing the Nazi invasion in 1940. Since then he had bounced around Hollywood, making one picture at Twentieth Century Fox, another for RKO, and two more as independent productions released through United Artists. His first UA project, The Southerner, was a moving tale of struggling cotton farmers in Texas, but in general Renoir found the Hollywood of the war years to be rocky soil for his kind of left-wing humanism. (His limited fluency in English didn’t help.) After finishing Diary of a Chambermaid for UA, he returned to RKO at the invitation of Joan Bennett to direct Desirable Woman, a romantic melodrama that had been in development for some time. Renoir had enjoyed working at RKO, and he looked forward to collaborating with producer Val Lewton, who had delivered for the studio with a series of artful, low-budget horror films (Cat People, I Walked with a Zombie, The Seventh Victim).

Ryan’s excitement about the picture only grew as he got to know the director. “One of the most remarkable men I’ve ever met,” he would say of Renoir. “Working with him opened my eyes to aspects of character that were subtler than those I was accustomed to.”15 His character was notably darker than anything he had played on-screen, a shell-shocked Coast Guard lieutenant now relegated to patrolling the misty Pacific coast on horseback. In one scene a friend at the base hesitantly informs him that the ship he was serving on has gone down, and the lieutenant is crushed. Not long afterward, on one of his lonely rides, he passes a wrecked ship, where he encounters a beautiful woman gathering firewood (Bennett). She brings him home to meet her husband (Charles Bickford), a famous painter now blind and embittered, and the lieutenant, consumed by lust for the woman, becomes an uneasy companion to the fractious couple.

In fact, Val Lewton had never really been interested in the project, and by the time principal photography commenced in late January 1946, he had been replaced by producer Jack Gross, who let Renoir do pretty much as he pleased. A month into the shoot, Charles Koerner — the head of production who had axed Pare Lorentz and Orson Welles — died suddenly of leukemia, which left Renoir even more unsupervised. He had never made a picture with so much improvisation on the set. “I wanted to try to tell a love story based purely on physical attraction, a story in which emotions played no part,” Renoir said.16 The open adultery of the source novel, None So Blind, already had been scrubbed away by the Production Code Administration, but there was something haunting about the lovers’ wordless attraction playing out right under the blind man’s nose.

Renoir also was intrigued by the story’s sense of solitude, something he felt was increasingly prized amid the chaos of modern life. “Solitude is the richer for the fact that it does not exist,” Renoir wrote. “The void is peopled with ghosts, and they are ghosts from our past. They are very strong, strong enough to shape the present in their image.”17 One scene showed the lieutenant, Scott, in his bed at the base, consumed by a nightmare. In a feverish montage, an Allied ship hits a mine and goes down, the image of a whirlpool pulls the eye in, bodies and ropes drop through the water, and Scott strides across the ocean floor in slow motion, stepping over the skeletons of his dead crewmates, on his way toward a lovely woman in a flowing gown. Before they can kiss, there’s an eruption of flame, an inferno that jolts Scott out of his dream.

Ryan — whose brother, father, and uncles all had preceded him to the grave — knew all about ghosts, and his strong streak of willful self-isolation made him an ideal collaborator for this kind of story. He would marvel at Renoir’s ability to “discover the true personality of the actor” and integrate it into a performance, a skill he would recognize in no other director but Max Reinhardt.18 Renoir found a neurotic quality in Ryan that had never been captured on-screen and would become the key element in his screen persona. Lying in bed, Scott confesses to his commanding officer that the nightmares have become chronic since he was released from the hospital. Ryan’s gaze shifts back and forth between two fixed points — the officer’s face and something awful a million miles away — as the tension gathers in his voice. The doctors have pronounced Scott healed. “But my head!” he exclaims in anguish, gesturing at it as if it were strange to his body.

The picture wrapped in late March, leaving Ryan free to tend to his expect ant wife. On Saturday, April 13, Jessica gave birth to a healthy baby boy, whom they named after his grandfather, Timothy, in the Irish tradition. Ryan’s next picture, a mediocre western called Trail Street, didn’t start shooting for three months, so the couple had plenty of time to care for and enjoy their new child and each other. Now that Ryan was back from the military, he worked either six days a week or not at all, loafing around in his mismatched pajamas until noon and working out later in the day. Jessica usually started writing in the morning — her second mystery novel, Exit Harlequin, was scheduled for publication in January 1947 — and worked until mid-afternoon. Determined homebodies, she and Robert relaxed in each other’s company, smoking, drinking, reading, and talking into the night.

Joan Bennett, Jean Renoir, and Ryan rehearsing The Woman on the Beach (1947). “One of the most remarkable men I’ve ever met,” Ryan called Renoir. “Working with him opened my eyes to aspects of character that were subtler than those I was accustomed to.” Franklin Jarlett Collection

Trail Street starred Randolph Scott as western hero Bat Masterson; Ryan got second billing as the villain, and whiskered “Gabby” Hayes dispensed cornpone comedy as Scott’s sidekick. (Four-month-old Tim Ryan made his screen debut as a baby being held by a woman in the frontier town.) Director Ray Enright had spent twenty years in the business without making a notable picture; he was quite a comedown after Jean Renoir. At the same time, Ryan’s collaboration with Renoir was in trouble. Desirable Woman was test screened on August 2 in Santa Barbara, where it was laughed at and jeered by an audience full of students. Renoir would confess later that he was the first to get cold feet, and he offered to reedit the film. Five or six weeks later, he emerged with a version that was shown to two disinterested parties: screenwriter John Huston, who argued that the lieutenant’s war trauma should be eliminated entirely, and director Mark Robson, who argued that it was central to the story. Renoir listened to Robson and moved the lieutenant’s fiery nightmare to the beginning of the picture.*

By late November, when Ryan and Bennett were called in for reshoots, Renoir had lost confidence in his original conception, and the love relationship became more conventional. Several dialogue scenes that explained the characters’ motivations were excised, which gave the action a detached quality. This garbled, seventy-minute cut of the picture, retitled The Woman on the Beach, would flop at the box office eight months later and end Renoir’s association with RKO. By then Renoir had grown close to the Ryans — Jessica adored him and his wife, Dido — and the two couples would keep in touch long after the Renoirs returned to France. “Bob Ryan is a marvelous person,” Renoir would later attest. “Professionally he’s absolutely honest in everything he does.”19 Almost everything — Ryan admired Renoir too deeply ever to tell him he thought The Woman on the Beach was a failure.

THE MOVIE BUSINESS boomed in 1946 as servicemen rejoined their families, which may explain why Peter Rathvon, the new president of Radio-Keith-Orpheum, allowed most of the year to pass before finally choosing forty-one-year-old Dore Schary to replace the late Charles Koerner as head of production. Schary was a comer: born to Russian Jewish immigrants in Newark, New Jersey, he had written plays in New York before arriving in Los Angeles to write for the screen and winning an Oscar for the MGM classic Boys Town (1938). Since then the tall, bespectacled young man had supervised B-movie production for Louis B. Mayer at MGM, and independent producer David O. Selznick had tapped Schary to head his new company Vanguard Pictures. Schary had great story sense, and he knew how to get the most out of a dollar. Selznick was generous enough to let RKO buy out Schary’s contract, and on January 1, 1947, Schary took charge of the studio’s production slate.

Two days later the United States experienced a dramatic political shift when the Eightieth Congress convened, its opening session carried for the first time on broadcast television. President Truman, battered by union struggles as he served out Franklin Roosevelt’s fourth presidential term, had been rebuked at the polls in November, when Republicans picked up fifty-five congressional seats and took control of the House of Representatives. Once the new Congress was sworn in, Republicans wasted no time in mounting a frontal assault on the Roosevelt legacy, and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), created in 1938 to investigate subversion against the US government, announced that a top priority would be uncovering communist influence in the motion picture industry.

A liberal Democrat, Schary took little notice of this as he moved into position at RKO. His formula for success involved socially conscious films that could be made on relatively small budgets, and the first script he sent into production was a murder mystery adapted from The Brick Foxhole, the novel that had so intrigued Ryan when he read it in the Marines. Producer Adrian Scott, who had scored at RKO with the Dick Powell mysteries Murder, My Sweet (1944) and Cornered (1945), had read The Brick Foxhole and was struck by the sequence in which soldiers beat a homosexual man to death. This would never get past the Production Code Administration, but what if the victim were a Jew instead? Scott hired screenwriter John Paxton to take a crack at the novel; their project, Cradle of Fear, would be the first Hollywood picture to deal openly with anti-Semitism in the United States.

The script had gone nowhere with Charles Koerner in charge, and market research indicated that only 8 percent of moviegoers would go for such a picture (compared to 70 percent for Sister Kenny, the Rosalind Russell drama RKO was still trying to get made three years after the Marines had refused to let Ryan appear in it). Schary was a different story — he read Cradle of Fear one night and pulled the trigger on it the next day, naming Scott as producer and Eddie Dmytryk as director. The budget was around $500,000, but half of that would go for the stars Schary felt would be needed to sell such a controversial picture to the public. Scott and Dmytryk would have to get Cradle of Fear in the can with what remained, shooting for about twenty days on existing sets. Paxton would remember his excitement after Schary gave them the go-ahead, as “a little parade went off around the lot (the writer just tagged along) looking for sets that could be borrowed or adapted, or stolen. An unusual procedure with front office blessing.”20

“What’s-a-matter, Jewboy? You ’fraid we’ll drink up all your stinkin’ wonderful liquor?” Montgomery (Ryan) and Floyd (Steve Brodie) close in on their victim, Samuels (Sam Levene), in Crossfire. Franklin Jarlett Collection

Ryan got along well with Schary, and when he learned the picture was in preproduction, he begged the new chief to let him play Montgomery. Schary must have been surprised: this wasn’t the sort of role that would lead to more love scenes with Ginger Rogers. Monty was repellent — ingratiating one moment, bullying the next, especially when he and his drunken pals are boozing it up with Samuels, who has met them at a bar and invited them back to his place. “Sammy, let me tell you something,” Monty slurs. “Not many civilians will take a soldier into their house like this for a quiet talk. Well, let me tell you something. A guy that’s afraid to take a soldier into his house, he stinks. And I mean, he stinks!” Things only get worse from there: when Samuels tries to get rid of them, Monty snaps, “What’s-a-matter, Jewboy? You ’fraid we’ll drink up all your stinkin’ wonderful liquor?” The word had never been uttered in a Hollywood picture.

The role might well blow up in Ryan’s face. But he loved the script, valued the idea behind the picture, and knew he was the man to play Monty. “I thought such a part would make an actor — not break him,” he later wrote.21 He lobbied Dmytryk — who, by this time, had directed him in his first picture (Golden Gloves), his biggest hit (Behind the Rising Sun), and his first romance (Tender Comrade). Schary and Dmytryk acceded, billing Ryan third behind Robert Young as Finlay, the pipe-smoking police detective who investigates the crime, and Robert Mitchum as Keeley, a jaded sergeant who tries to save the confused young Private Mitchell from being framed by Monty. Schary also brought in some first-rate supporting players: Sam Levene as Samuels; sultry, blond Gloria Grahame (It’s a Wonderful Life) as a hooker who briefly adopts the private during his nocturnal wanderings; and, in the picture’s second-creepiest role, craggy Paul Kelly as a man who hangs around her apartment and keeps changing his story about their relationship.

When the picture came out, Ryan would publish two stories under his own byline, in publications no less divergent than Movieland and the Daily Worker, that explained his rationale for taking the role. “Convictions are nice things to have,” he wrote in the Worker, “but when close friends tell you that you’re jeopardizing your career by taking a role you believe in — well, it makes you stop and think.” The picture was unlikely to convert any hardened anti-Semites, he conceded. “No one picture, no one book, no one speech could accomplish that. It’s the cumulative effect that counts.”22 In Movieland he argued that the picture’s subject was broader than anti-Semitism: “We all stand to lose if fascism comes. Not just the Jews. The Irish, the Catholics — and I’m both of those — the Negroes, labor, the foreign born, everyone is done for whose color, or religion, occupation or political belief is distasteful to some new paperhanger-turned-Strong Man.”23

Once he had been cast, Ryan dove into the part. He studied back issues of Social Justice, a frequently anti-Semitic magazine edited by the Roman Catholic priest and populist demagogue Father Charles Coughlin. Launched in 1936, it had serialized the fraudulent Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which purported to be a Jewish plan for global conquest, and published one article by Coughlin that borrowed passages from a speech by Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda minister, about the threat posed by communism, atheism, and the Jewish people. Ryan also paid a visit to Jean Renoir, who was still wrestling with The Woman on the Beach, and asked him about the fascist sympathizers he had known in France. Renoir spent the afternoon telling him stories, and Ryan came away convinced that the key to Montgomery was a deep-seated sense of inferiority.

If Schary wanted to test the limits of his authority at RKO, he succeeded; in early February, Rathvon sent him a memo expressing his doubts that Cradle of Fear would do anything to reduce racial intolerance. “Prejudiced Gentiles are not going to identify themselves with Monty and so feel ashamed of their prejudices,” wrote Rathvon, a smart and cultured man whom Schary respected. “Rather they may be resentful because they feel we have distorted the problem by using such an extreme example of race hatred.”24

On another front, Darryl F. Zanuck, president of Twentieth Century Fox, informed Schary that Fox had a picture about anti-Semitism on the boards, Gentleman’s Agreement, and suggested he cease and desist. “We exchanged a few notes,” Schary recalled, “then a phone call during which I was compelled to tell him he had not discovered anti-Semitism and that it would take far more than two pictures to eradicate it.”25 Determined to beat Gentleman’s Agreement out of the box, Schary stepped up production on Cradle of Fear; principal photography would begin Monday, March 3.

Scott and Dmytryk went over the script carefully, working out every shot in advance to save time on the set. Once the cameras began rolling, Dmytryk fell into a pattern of shooting for about six-and-a-half hours each day, then using the last couple of hours to rehearse the next day’s scenes; this gave the crew time to set up the first shot and enabled the players to come in the next morning ready to go. The sets looked cheap, so Dmytryk placed his key lighting low in the frame to throw lots of shadows; for a scene in which Monty bullies his accomplice, Floyd, the only light source was a table lamp, revealing some of the uglier lines in Ryan’s face. Dmytryk also chose his lenses to make Monty look increasingly crazed: at first his close-ups were shot with a fifty-millimeter lens, but this was reduced to forty, thirty-five, and ultimately twenty-five-millimeter. “When the 25mm lens was used, Ryan’s face was also greased with cocoa butter,” Dmytryk recalled. “The shiny skin, with every pore delineated, gave him a truly menacing appearance.”26

The real menace, though, lay in Ryan’s deft underplaying. Critics would stress the intelligence he brought to his heavy roles, but in the case of Monty, an ignorant blowhard, the defining characteristic was an animal cunning. In his first two speaking scenes, Monty is interrogated by Detective Finlay, and in both instances he hastens to defend his pal Mitchell, whose wallet has been found at the crime scene, even as he directs suspicion toward him and away from himself. In the second interrogation, with Sergeant Keeley looking on, Monty grows angry at Finlay’s questioning and barks at him, promising, “You won’t pin anything on Mitch, not in a hundred years!” Catching himself, he drops his gaze, glances back and forth at the two men, and apologizes, pleading, “It’s just that I’m worried sick about Mitch.”

This was Ryan’s first picture with Mitchum, whose roughneck adventures during the Depression (boxing, riding the rails, doing time on a chain gang) were even more dramatic than his. The men liked and respected each other, but their upbringings set them apart; Mitchum had grown up poor and dropped out of high school, and his politics were more conservative. Ryan might have held forth on the dangers of fascism, but according to Dmytryk, when a reporter on the set asked Mitchum why he was making the picture, the actor replied, “Because I hate cops.”27 In fact, he was annoyed at having been lured back from a Florida vacation by Scott with the promise of a great part, only to learn it was no such thing (Scott confessed that they needed him for his box office clout). Mitchum must have realized at some point that Ryan was walking away with the picture.

The only real complication to emerge during production was how to get rid of Monty after the detective has tricked him into exposing himself. Screenwriter John Paxton wanted to add a scene in which Monty goes to trial, but Schary scotched this idea. Schary later claimed that the picture’s original ending had MPs cornering Monty and shooting him down “like a rat,” which might have increased the audience’s sympathy for him.28 Instead Monty breaks away from the cops and runs out into the street; from a second-floor window, the detective orders him to halt and then calmly dispatches him with a single bullet in the back. Paxton was appalled when he saw this, but he had no say in the matter. Schary also changed the release title to Crossfire, which had no relevance to the story but sounded great.

Principal photography wrapped on Saturday, March 29, after only twenty-four shooting days. The project had come together so quickly that there was no time for the sort of front-office meddling that might have watered down the story. A few weeks later Ryan attended a rough-cut screening with Scott, Dmytryk, and a handful of RKO executives. None of the other cast members was there, but he was eager to get a look at his performance. Watching the story unfold, Ryan knew he had nailed the character. About fifteen minutes into the picture, the detective interrogates Monty, asking him about the victim. “I’ve seen a lot of guys like him,” Monty explains, conspiratorially. “Guys that played it safe during the war? Scrounged around keepin’ themselves in civvies? Got swell apartments, swell dames? You know the kind…. Some of them are named Samuels, some of them got funnier names.” Later, as Monty smacks Floyd around, his rage boils over: “I don’t like Jews! And I don’t like nobody who likes Jews!”

After the screening was over and the lights came up, the room was silent. Finally, one of the RKO suits spoke up: “It’s a brave thing you’ve done, Ryan. You’re gambling with your career, of course.” Another piped up: “Really courageous.”29 Taken aback, Ryan walked out of the screening room, crossed the lot, picked up his car, and headed home. Given what he had seen in the Marines, talk of bravery embarrassed him. But the executives’ remarks were the first reaction he had received outside of the cast and crew, and their subtext was obvious: if the public turned against Ryan, RKO would simply cut him loose.

*The film would ultimately be released as Till the End of Time (1946), starring Robert Mitchum and directed by Edward Dmytryk.

*A definitive genesis of the movie can be found in Janet Bergstrom’s “Oneiric Cinema: The Woman on the Beach,” Film History 11 (1)(1999): 114–125.