Читать книгу Architecture. Dialectic. Synthesis - - Страница 16

Essays on the History of Architecture by Antithesis

Cubicity – Sphericity / Straightness – Curvilinearity

ОглавлениеSphericity relates to cubicity in the same way that identity relates to difference. Sphericity is the state of a form when all its parts are so identical that it is no longer possible to distinguish any parts on the surface of the form. From the absence of parts, it follows that a spherical form is a pure identity that has no internal boundaries. The ball is infinite for an ant crawling on it, although it is finite for the person holding it in his hand.

The geometrically modified boundary category is an edge. An edge is what divides a form into distinct parts and makes it differentiated. A form containing edges, and therefore faces, is a difference from the point of view of eidos. It's a cubic form.

Thus, a spherical form is a single surface in which we cannot distinguish parts (faces), since we have no edges (borders). The cubic form is quite clearly composed of several clearly distinguishable surfaces.

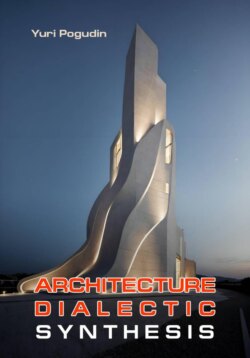

The synthesis of sphericity and cubicity (facetedness) is a form containing both sphericity and cubicity. This form, on the one hand, is spherical, streamlined, and has no edges, and on the other hand, it is divided into distinct faces. Dialectics strives to preserve the subject as a whole and therefore insistently reminds that any sides, aspects, predicates, etc. of any subject are both identical and different at the same time. An object is a synthesis of its sides, properties, etc. in one indecomposable unity.

The limiting expressions of sphericity and cubicity in the geometric domain are, respectively, a ball and a cube. The ball is a pure identity, since it has the same curvature at all its points, and is completely identical to itself in any spatial position, absolutely symmetrical with respect to any axis passing through its center. The cube perfectly expresses the principle of facetedness, since all its adjacent faces are perpendicular. Perpendicularity is the ultimate degree of difference between two or more straight lines and planes. Any other angle between straight lines or planes will be their convergence, which tends to complete coincidence of the elements (at an angle of 0 or 180 degrees).

Let's give examples of cube and sphere synthesis:

1) a cube made up of balls or a ball made up of cubes

2) a straight cylinder with a height equal to the diameter of the base (one of its orthogonal projections coincides with the projection of a ball (circle), and the other with the projection of a cube (square)

3) the eighth part of the ball is the most complete synthesis (from the one side, an exact cube, and from the other, an exact ball)

4) all the countless complex stereometric forms with rectilinear and curved surfaces

The antithesis of sphericity and cubicity becomes especially intense when we take it in its mythological aspect. Sphericity is a property directly visually and mythologically attributed to the sky, as evidenced by such a stable expression as "celestial dome". Both the physical and spiritual sky possess the property of "globularity". "… The world of bodiless powers, or the Heaven, is a sphere that has a straight line around it <…> We look at the Heaven so that the Sun is between it and us. Therefore, we look at the Heaven from God's side. It is quite understandable that it appears to us as an overturned Chalice. The Heaven is a Chalice not because it seems so to our subjective gaze, but it seems so to us because the Heaven, in its inner and most objective essence, is nothing but a Chalice.43"

If the heaven is a chalice, then what is the earth? According to the principle of a simple opposition, the earth is a cube. According to A. F. Losev, the ancient Greek thinkers associated the element of the earth exactly with the cube44. The body is an earthly, earthy principle in man (Adam was created from the earth), and therefore "the whole body, made up of individual members, is square.45" The body is square not in appearance, but in the sense of its relation to the spirit, expressed geometrically.

Thus, within the spherical nature itself, we find both sphericity (heaven) and cubicity (earth). According to this division, the antithesis of top and bottom appears in the building: the roof, which interacts with the sky, and the foundation with the walls, which determine the interaction with the earth. It is easy to notice that most roofs and ceilings in the "old" architecture of different styles and eras are often spherical (domes, arches, cones, etc.). Both the Pantheon and St. Sophia of Constantinople are covered by a spherical form. The lower part of buildings, on the contrary, is solved as faceted, cubic. This correspondence of the bottom of the building to the cubic form, and the top to the spherical form, is probably partly due to the round shape of the human head – the upper part of his body. In ancient Russian architecture, there was a direct associative correlation: the dome is the helmet of a warrior hero.

The antithesis of "ball-cube" has a deep philosophical significance. It geometrically expresses the semantic opposites "nature-technology", "heaven-earth", "spirit-body".

In this regard, it is possible to suggest a classification of architectural structures. An orthogonally parallel structural system – a rack-and-beam one – corresponds to the cube. Arched, vaulted, shell-shaped structural systems correspond to the ball.

The struggle between the cubic and the spherical permeates the history of architecture. In the history of classical architecture, these trends were most obviously crystallized in the rationality of Classicism and the emotionality of the Baroque, which became a ramification of Renaissance synthetism. An example of the synthesis of these styles is the Palace Square in St. Petersburg.

In modern architecture, this struggle is even more acute, on the basis of which A. V. Ikonnikov argued that "it was only in the architecture of the twentieth century that trends emerged that focused on one of the polarities that had always previously acted inseparably.46"

The cubic form is often correlated with the technical one, and the spherical form with the natural, bionic one, although this correlation is optional. The architecture of Antonio Gaudi may serve as an example of the second case. One of his most famous works, the Casa Milà in Barcelona (1902-1910), is characterized by its "naturalness", smoothness of lines, curves, and fluidity of form. This is an example of Art Nouveau architecture, tending towards natural, curved outlines.

In German architecture of the 1920s, the "struggle between cube and ball" was expressed in the confrontation between neoplasticism (Theo van Doesburg, Piet Mondriaan, Gerrit Rietveld) and expressionism (Erich Mendelsohn, Hans Poelzig)47.

This antithesis can also be traced in Soviet architecture – in the difference between the design methods of constructivists and rationalists. "Constructivist buildings also reflect orthogonal drawings in their style, and there is little plasticity in them. The works of rationalists are more plastic, often there are no facades at all that could be drafted in orthogonal drawings.48"

Ivan Leonidov is a non-typical constructivist. "Back in the late 20s and early 30s, Leonidov used forms with a second-order generating curve, shell vaults in his projects along with rectangular prismatic volumes…"49.

Expressionism has become a relatively synthetic trend in modern architecture, one of the representatives of which is E. Mendelsohn. "Unlike the orthogonal, monochrome solutions of the modernists, Mendelsohn uses the contrast of orthogonal forms with curved ones.50"

In the history of architecture of the twenty-first century as a whole, there is a strong bias towards complicated curved forms, accompanied by criticism of modernism51.

Let's move on to the next point of the architectural form – let's consider it not only by itself, but also in relation to the otherness of space.

43

Losev A.F. (1999) Lichnost i absolyut [Personality and the Absolute], Moscow: Mysl, – p. 500, 505. (in Russian)

44

See Losev A.F. (1993) Bytie. Imya. Kosmos [Genesis – Name – Cosmos]. Moscow: Mysl. – p.300. (in Russian)

45

The thought of St. Ambrose of Milan. Quoted in: Zubov V.P. (2000) Trudy po istorii i teorii arkhitektury [Works on the History and Theory of Architecture]. Moscow: Iskusstvoznanie. – p. 268. (in Russian)

46

Ikonnikov A.V. (1986) Funktsiya, forma, obraz v arkhitekture [Function, Form, Image in Architecture]. Moscow: Stroyizdat. – p. 177. (in Russian)

47

See: Ikonnikov A.V. (2001) Arkhitektura XX veka. Utopii i realnost [Architecture of the Twentieth Century. Utopias and reality]. Volume 1. Moscow: Progress-Tradition. – pp.186-193. (in Russian)

48

Khan–Magomedov S. O. (1996) Arkhitektura sovetskogo avangarda. Kniga pervaya. Problemy formoobrazovaniya. Mastera i techeniya [Architecture of the Soviet Avant-garde. Book One. Moscow: Stroyizdat. – p. 242. (in Russian)

49

Alexandrov P.A., Khan-Magomedov S.O. (1971) Ivan Leonidov. Moscow: Stroyizdat, p. 105. (in Russian)

50

Maklakova T.G. (2000) Arkhitektura XX veka [Architecture of the Twentieth Century]. Moscow: Publishing House of the Association of Construction Universities. – p. 45. (in Russian)

51

See, for example, The Parametricist Manifesto (2008) by Patrik Schumacher.