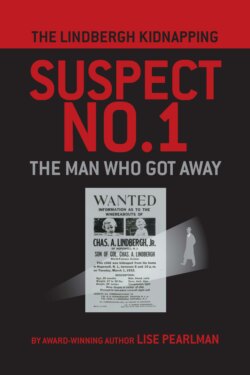

Читать книгу THE LINDBERGH KIDNAPPING SUSPECT NO. 1 - Lise Pearlman - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4.

The Search for the Perfect Mate

AFTER his historic flight, Lindbergh was viewed as the most eligible bachelor in the country, if not the world. Deluged by fan mail and hounded by autograph seekers, the Midwestern pilot was fawned over by women and teen-aged girls everywhere he went. The unwelcome attention started with a young Parisian woman who rushed up to plant a red-lipstick kiss on his cheek shortly after he landed at Le Bourget.

Star-struck girls who idolized “Lindy” had no idea that at age 25 he had never dated. Indeed, not long before, when he lived in obscurity with fellow pilot Philip “Red” Love in St. Louis, every time Love got on the telephone with a young woman he was interested in, Lindbergh “sang, shouted, whistled, stamped his feet — he banged things, dropped things, rattled things, screeched things” to force his frustrated roommate to end the call.

Facing hordes of reporters and fans on his return from Paris in May 1927, the reclusive pilot was woefully unprepared for the spotlight. He still had the uncouth habits of spitting on the ground in public and wiping his nose on his sleeve. He was tongue-tied when it came to small talk. He did not have his late Congressman father’s affinity for glad-handing, nor had he ever absorbed his mother’s social skills.

Philanthropist Harry Guggenheim immediately took the awkward new celebrity under his wing. The Swiss Jew headed the Foundation for Aeronautical Research. Guggenheim sequestered Lindbergh at his Long Island estate and helped Lindbergh acquire a suitable wardrobe and improve his social skills. Of greatest consequence, Guggenheim paired Lindbergh with his own attorney, Henry Breckinridge, for legal and business advice. The two became an inseparable team driven by unbridled ambition.

Breckinridge had his own far-reaching connections to powerful men. He was then 41 and in the prime of his career. The six-foot-one Ivy Leaguer, from a long line of bluebloods on both sides, was just a generation removed from the schism in his Kentucky family over the Civil War. Two of his father’s brothers fought for the Confederacy, while his father became a Union officer, and later rose to the rank of Major General before retiring.

With his family connections, a Princeton college degree and a law degree from Harvard Law School, Breckinridge’s career took off quickly. In 1912, he supported New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson (former President of Princeton) as the Democratic candidate for President. After Wilson won, he tapped Breckinridge to serve as Assistant Secretary of War — at the age of 27. Lindbergh was likely far more impressed that Breckinridge won a bronze medal in fencing in the 1920 Summer Olympics and was now training for the 1928 Olympics as the head of the U.S. fencing team. Breckinridge was also an amateur pilot. Lindbergh soon trusted Breckinridge implicitly with all his affairs.

So many accolades and opportunities had begun cascading upon the Minnesota barnstormer his head was spinning. After Congress voted Lindbergh the first medal of honor awarded a civilian, requests for endorsements poured in, totaling $5 million in what seemed like a blink of an eye. Lindbergh was immediately offered a starring role in a Hearst-produced movie opposite the newspaper mogul’s mistress, Marion Davies. He accepted the offer but managed to wiggle out of it after Breckinridge convinced him he would regret it.

Chief among the proposals Breckinridge suggested Lindbergh should accept was Guggenheim’s plan to bankroll a four-month promotional tour for commercial aviation. Lindbergh earned $50,000 visiting every one of the then forty-eight states, landing in over eighty cities that each honored him with a parade. By one later estimate, nearly a fourth of all Americans turned out to see him. Throughout this tour Lindbergh was accompanied by a bodyguard, John Fogarty, a former detective, who had worked with one of Breckinridge’s brothers when he was in the New York District Attorney’s office.

Though Lindbergh turned down millions of dollars in offers, and donated gifts to museums, he accepted shares in new airline companies, which asked him to sit on their boards. Lindbergh soon also profited handsomely from his autobiography. Less than a year since he had scraped by, counting every penny, Lindbergh would become a millionaire, never in danger of going broke again. He made sure his mother was financially secure, too.

That summer and fall, Guggenheim introduced him to wealthy patrons who immediately embraced the national hero as one of their own. Lindbergh was of white Protestant stock at a time when control of America remained firmly in the hands of those with a similar religious and racial makeup. Of pure Nordic descent on his father’s side, the tall blond pilot, was the very image the elite wanted to project of traditional wholesomeness, bravery, and self-reliance.

From his arrival in New York after his flight to Paris, in or out of his flight clothes, on or off the field, journalists and cameramen hounded the aviation pioneer. This was only the beginning of an insatiable media appetite for family photos and details of his background for newspaper editors to manipulate to fit the image of the hero the public craved to admire.

During his tour across America that summer, Lindbergh focused single-mindedly on expanding interest in commercial aviation. He was repulsed time and again by obsessed female fans who made off with souvenir pillow slips he had slept on or underwear they filched from his hotel laundry service. More than once someone absconded with his fedora left with a restaurant hat checker. He took to scowling at the camera and behaving rudely toward mobs of adoring fans. He soon began burning all the myriad letters he received without having anyone open them to sort out those he might wish to read and consider a reply.

Lindbergh remained surrounded by pretty young women almost everywhere he went. Yet he found it difficult to get beyond the awkward exchange of pleasantries. It got under his skin that the press wrote up any hint of interest he showed in the few females he found worthy of his attention. Some reporters even fabricated dates with women he had never met. For relief, Lindbergh turned to his usual source of amusement. He annoyed his new assistant Harry Bruno with practical jokes: “He’d put a fish in your camera, a blunt blade in your razor or switched the keys in your typewriter.” The public never realized the extent of that nasty habit.

By late July 1927, New York Times reporter Carlisle MacDonald was nearing completion of the ghostwritten manuscript for Lindbergh’s autobiography that Lindbergh had agreed to do in May. Lindbergh read the draft while secluded at Guggenheim’s Long Island estate. He became incensed at MacDonald’s presumptuous retelling of his life. Lindbergh remained at the estate while he set about rewriting the story in his own words. What disappointed Lindbergh most was that the ghostwritten draft left out all of his pranks. Rewriting the book that fall, the newly acclaimed paragon of “American idealism, character and conduct” took special delight in inserting some of his more memorable pranks, as well as racist anecdotes from his barnstorming days. In retelling some of his favorite stories, Lindbergh was careful to suppress incidents of his most sadistic behavior.

The “most notorious and cruel” of Lindbergh’s practical jokes involved a younger pilot he recruited to his airmail team — Harlan “Bud” Gurney. One night when the two shared a room at a boarding house, Lindbergh filled the water pitcher with kerosene. Gurney quickly drank two dippersful from the pitcher before he realized he was not downing water. He wound up in the hospital with a severely burnt throat, lucky to be alive. Uncharacteristically, Lindbergh later regretted that he had not devised a more “moderate” practical joke to teach Gurney a lesson for Gurney’s thoughtlessness in not doing his fair share of refilling the pitcher for the two of them. The near disaster did not dissuade Lindbergh from devising cruel tricks against other hapless victims.

As Lindbergh worked on his autobiography, “WE,” he mostly avoided all women except his mother. Yet the tall blond hero began seriously considering his marriage prospects. Lindbergh approached the issue of marriage and family scientifically. In the summer of 1927 Lindbergh had received a plaque from the Minnesota Eugenics Society “in recognition of his superior hereditary endowment.” He felt he had a special obligation to pass on his acclaimed genes to help perpetuate the most advanced race of people. By then, eugenics had become firmly entrenched as “the religion of aristocrats” who believed “Western civilization was in danger of committing racial suicide as a result of the rapid reproduction of the unfit coupled with a decline in the birth rate of the supposedly ‘better’ classes.”

Yet Lindbergh was also painfully aware of his lack of social skills: dancing, small talk and etiquette. Getting up the nerve to invite a woman to the theater or a restaurant totally baffled him. He did know what he wanted to avoid. He had been disgusted by the paid sex pursued by his fellow Army recruits. Lindbergh felt strongly the whorehouse was “not an environment conducive to evolutionary progress.” He was just as nauseated by the one-night stands of his libidinous pilot buddies. Their dating habits did not reflect “selectivity, hardly any desire for permanence and children.”

A year before Lindbergh’s flight, prominent doctors, lawyers, politicians and professors launched an organization expressly devoted to improving the gene pool, the American Eugenics Society (AES). Both the AES and the more established American Genetics Association (AGA) counted among their members the nation’s leading geneticists, strongly supported by powerful politicians and wealthy philanthropists, including the nation’s two richest men, steel magnate Andrew Carnegie and oil baron John D. Rockefeller.

Lindbergh likely first became aware of the AES in 1926 when it started an annual national contest promoted in county and state fairs — places where barnstormers then often performed. Dubbed “Fitter Families for Future Firesides,” these “Fitter Family Contests” awarded annual trophies through competition. The contestants vied for designation by AES doctors as the couple who produced “the most viable offspring based on physical appearance, behavior, intelligence, and health.” Invariably, the winners were those of white Northern and Western European ancestry.

By the summer of 1927, Lindbergh’s own elevated view of self-worth matched eugenicists’ concept of ideal characteristics — narcissism that groupies reinforced everywhere he went. Looking for a wife in 1927, Lindbergh embraced the AES standard. He wanted a woman of “good health, good form, good sight and bearing.” Biographer A. Scott Berg describes Lindbergh’s formula as “more about animal husbandry than human relations…. emoting less about choosing a wife than a farmer might in selecting a cow.” But Lindbergh saw human procreation through that same lens. He felt he had a special obligation to pass on his acclaimed superior genes to help perpetuate the most advanced race of people.

By his twenties, Lindbergh had clearly absorbed the knowledge that Nordic supremacy was a widely shared view. He, too, believed other races were inferior. Indeed, no one who came of age in the 1920s could escape the white supremacist message underlying the national agenda. In 1924, Congress passed a draconian immigration policy aimed at homogenizing the gene pool by excluding Asian immigrants and severely limiting the number of “Hebrews, Slavs, Catholics and Negroes” permitted to immigrate to the United States. Birth control advocate Margaret Sanger reduced the policy to a slogan: “More children for the fit; less for the unfit.”

By the late 1920s, the widely publicized goal of eugenicists was both to purge the gene pool of as many people with “inferior” traits as possible and to encourage procreation by the best white families. Support for the eugenics movement hit its high point less than three weeks before Lindbergh’s solo crossing of the Atlantic. That was when the United States Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling endorsing forced sterilization of those deemed unfit. The Supreme Court’s ruling in Buck v. Bell prompted a major push to pass legislation to rid the country in future generations of “the socially inadequate” — defectives, dependents and delinquents. All of this coincided with the national campaign to encourage preferred white couples to compete in creating Fitter Families for Future Firesides.

It is easy to see how Lindbergh felt compelled to be part of the solution. Like Teddy Roosevelt, who had been C.A. Lindbergh’s hero,

Lindbergh believed people exhibiting excellent family traits had a duty to intermarry and produce numerous offspring. Lindbergh considered it important to have a definite objective in mind before committing himself to a plan of action. He decided he could best help improve the gene pool by producing twelve children like himself. He focused on finding a marriage partner with “good heredity,” a lesson learned from his “experience in breeding animals on our farm.”

In the fall of 1927 when Lindbergh worked weekdays on rewriting his autobiography, Guggenheim continued his own mission. One wonders if he was inspired by the character Professor Henry Higgins in George Bernard Shaw’s enormously popular play “Pygmalion” (later remade as the musical “My Fair Lady”). Guggenheim similarly planned to transform his houseguest from an uncouth barnstormer to the toast of high society. The debonair New Yorker had already fitted Lindbergh with a tuxedo and several hand-tailored suits. That fall, the wealthy philanthropist featured Lindbergh at numerous weekend parties held at the Guggenheims’ Long Island mansion.

Lindbergh was still a virgin. He shunned women who wore too much makeup. He did not play tennis and found it awkward to learn parlor games or chat about movie stars or the latest styles. He was not comfortable holding doors open, discussing literature or escorting women to the theater. He studied girls’ bodies to see if the clothes they wore might be obscuring defects in their builds. He invited some of them swimming to see for sure. But Lindbergh was wary of showing too much interest in a particular young woman. Otherwise, the newspapers were prone to instantly have them engaged.

While being feted at millionaires’ private estates, it crossed Lindbergh’s mind that one of their daughters would be a smart pick. He wanted a mate with a high-achieving father, a woman who would enjoy air travel and was game to assist him on future flights. He wanted a free-thinking girl, not a regular churchgoer with strong religious convictions. He also assumed she would be Caucasian. Guggenheim introduced the shy celebrity to a who’s who of powerful men: Herbert Hoover, Orville Wright, John Rockefeller, and J. P. Morgan among them.

Dwight Morrow, whom Lindbergh had already met, attended gatherings there as well. Morrow was a self-made man, who quickly mastered any subject he was assigned. J. P. Morgan had quickly nurtured Morrow’s consummate negotiating skills. When Lindbergh was still in high school, Morrow, through Morgan’s influence, had served as the top American civilian aide to General Pershing in France in World War I. (Morrow’s path to riches exemplified the war profiteering C.A. Lindbergh had railed against at the time.)

When Lindbergh met his future father-in-law, Morrow occupied the powerful position of general counsel of Morgan’s bank. Morrow was also one of the trustees of the Guggenheim Foundation for the Promotion of Aeronautics and had been one of the first dignitaries to greet Lindbergh on his arrival in Washington from Paris. Morrow then headed a board created by President Coolidge to elevate the air service to an Army Air Corps. At the time, an American war with Mexico loomed as a distinct possibility. The Coolidge administration hoped to avoid hostilities between the two countries.

On meeting Lindbergh, Ambassador Morrow instantly realized the pilot’s potential value in smoothing relations with the nation’s southern neighbor. That fall, Morrow invited Lindbergh to his apartment in New York and persuaded the pilot to take the Spirit of St. Louis on another international trip before donating it to the Smithsonian — an historic nonstop flight to Mexico City from Washington, D.C.

Anne Morrow first met Charles in December 1927, after her father engineered that public relations coup. At the invitation of Mexico’s President, Lindbergh took off from the nation’s capital on December 13, 1927, shortly after noon and flew through the night to Mexico City. Lindbergh emerged from the cockpit to yet another elaborate hero’s welcome. Dwight Morrow brought the pioneering aviator back to the embassy and convinced his wife to invite Lindbergh and his mother to join their family for the holidays. At first, only the Morrows’ two youngest children were present with their father and mother at the embassy: Dwight, Jr., aged nineteen and Connie, aged fourteen.

On December 19, 1927, the Morrows’ two eldest daughters took the train to Mexico City to join their family for Christmas. Like their mother, both attended Smith College. Elisabeth, age 23, had already graduated and Anne, then 21, was in her senior year. Though Anne enjoyed her older sister’s company, she could not help feeling inferior. Elisabeth was the taller of the two, and a striking blonde adept at witty conversation. (She was named for her mother, but the Morrows spelled her first name with an “s” instead of a “z.”) Elisabeth seemed to draw beaux at will.

Anne was a petite brunette, pretty, but with her mother’s less arresting features. Though athletic, she was bookish by nature, a tendency that filled her with self-doubt in mixed company. Anne did possess dazzling, violet-blue eyes, and two other things her older sister did not — excellent health and total infatuation with Lindbergh.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Dwight_Morrow.jpg

Ambassador Dwight Morrow

Source: Smith College Archives

Elizabeth Cutter Morrow

Source: Lansing State Journal, December 3, 1934

Elisabeth Reeve Morrow

At the request of Ambassador Dwight Morrow, newly minted American hero Charles Lindbergh made an historic nonstop flight to Mexico City in December of 1927 From Washington, D.C. Invited to spend Christmas with the Morrows and their four children, he was instantly attracted to their oldest daughter Elisabeth.