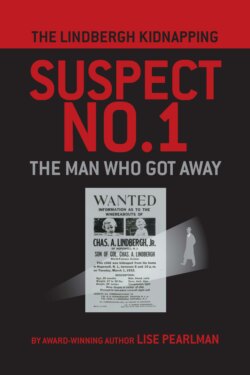

Читать книгу THE LINDBERGH KIDNAPPING SUSPECT NO. 1 - Lise Pearlman - Страница 24

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1.

The Police Arrive

THE HOPEWELL police recorded that it was 10:22 p.m. when Olly Whateley first called to alert them that the Lindberghs’ son was missing. The state police received a similar call at 10:25 p.m. State troopers, county detectives and local police had overlapping jurisdiction. The Lindbergh’s large estate straddled both Mercer and Hunterdon Counties. Technically, the house itself was over the line in the township of Amwell in Hunterdon County; the town of Hopewell was situated in Mercer County.

Rushing from Hopewell, Police Chief Harry Wolfe and Constable Charles Williamson intercepted Olly Whateley headed to town to buy a flashlight. Since the policemen had flashlights, Whateley turned around and came back with the officers around 10:35 p.m. Lindbergh called the state police at 10:40 p.m. to alert them that he had found an envelope in the nursery. This was new information since the first call; no one had apparently yet spotted it when the police were first notified of the child’s disappearance over fifteen minutes earlier.

Once the two local policemen entered the house, the nursery was the first place Lindbergh took them. Betty Gow said the room had been dark when she found the child missing at 10 p.m. just as it was when she left the room just over two hours earlier. Now the light was on. Lindbergh warned the two Hopewell officers against touching any surface. He wanted to leave the room as it was for the New Jersey State Police, including an unopened envelope on a windowsill to the right of the fireplace on the east wall. Lindbergh told Chief Wolfe that was where the kidnapper must have entered and exited. It was the one window for which the women could not make the shutters close when they put his son to bed earlier that evening. Lindbergh said he was in the study directly below the nursery from 9:30 until 10 p.m. and heard nothing unusual.

Looking around the room, it amazed the police chief that the nursery was full of undisturbed furnishings — quite a feat for a kidnapper to negotiate in the dark without knocking anything over. Chief Wolfe tried to figure out how that second-story window could have been the point of entry. The fellow would have had to stand on a ladder propped up against the house. Inside the room under the windowsill where the envelope lay sat a large chest, with a small suitcase on top and the roof of a wooden Noah’s ark on its surface. The police chief observed a smudge mark on the suitcase and on the floor nearby. But Wolfe was more “surprised at what he did not see.”

Having investigated many other crime scenes, Harry Wolfe expected much more evidence to be apparent this soon afterward. He saw no blood on the crib or the sheets or any place else. No handprints either. The standing screen that stood between the French window and the crib showed no signs of even having been moved. The window where the sealed envelope sat on the sill did not look like it had been forced open. The police chief concluded that to get through the window, a would-be kidnapper would have to be quite an acrobat to launch himself over the stack of obstacles without disturbing any part of it. There was no indication that the chest below that window had moved at all. The kidnapper would also have had to land on his feet in the dark without making any loud noise or disturbing any other furnishings.

Harry Wolfe considered the next step. He wondered how a kidnapper could possibly have carried a toddler out the same window without disturbing the chest that blocked his exit path. He later explained: “The culprit would have pushed it around in order to gain a secure foothold, he certainly would not have taken time to push the chest back into place, especially if he had a baby in his arms and was in the act of a desperate crime. But bear in mind — the chest had not been moved.”

Lindbergh then took the policemen to the yard to view with the aid of their flashlights ladder prints under the nursery window. Because of the mud, workmen at the farmhouse had placed planks on the ground around the house to walk on. Without a flashlight someone out in that yard on that stormy night might have easily tripped. Lindbergh guided their way out 75 feet or so to a spot where the Hopewell officers’ flashlights revealed a three-part sectional ladder — two parts lying together and one about 9 feet away. Constable Williamson was surprised that Lindbergh led them directly to the ladder. Lindbergh then pointed out to the two local policemen a chisel and dowel on the ground not far away. Back in the house at 10:53 p.m. Lindbergh called the state police again to say he had just located two ladders in the yard.

The head of the New Jersey State Police was 36-year-old Colonel H. Norman Schwarzkopf. (His son, American General H. Norman Schwarzkopf, would lead the Gulf War coalition in 1991 that ousted Saddam Hussein from Kuwait.) When Lindbergh’s first call came into headquarters in Trenton, Schwarzkopf had sounded the alarm right away via a teletyped broadcast. With Lindbergh’s blessing, the first allpoints bulletin was issued well before any state police arrived at the scene. By 11 p.m., New Jersey State Police were stopping and searching all cars headed toward Manhattan via tunnel, bridge and ferries and at checkpoints on the highways to Pennsylvania. Every license plate number they saw was recorded.

The Coast Guard and all airports were also placed on alert. New Jersey Governor Harry Moore immediately sent telegrams to his counterparts in every state in the region seeking their help. The news was already on every radio station nationwide and set in type for shocking front-page headlines on March 2 around the world from Paris and London to Moscow, from Shanghai to Cape Town, South Africa and all the way to Sydney, Australia.

New Jersey State Trooper Joseph A. Wolf arrived twenty minutes after the local police. It was then about five minutes to eleven. He sent for other troopers to join him and interviewed all the members of the household. He noted in a detailed report that night that the ground was saturated at the time of the crime; it was “very dark”; the temperature was about 34 to 40 degrees Fahrenheit and “a strong wind was blowing.” He also learned from Lindbergh that when Lindbergh first visited the nursery after Betty Gow reported his son missing from his crib, Lindbergh immediately noticed a window on “the east wall of the nursery was unlocked with the right half of the outside shutter open” and saw that a plain envelope sat on the sill. He told Trooper Wolf the “envelope had been left there by the person or persons who carried away his son.”

Lindbergh assured Wolf that he did not disturb anything in the room but went outside accompanied by Olly Whateley and explored the grounds. Wolf reported that they found footprints near the nursery and the ladder “some distance from the house” on the east side of the house before Lindbergh instructed Whateley to call the Hopewell police, before the State police were alerted, and before Lindbergh sent Whateley to town to get a flashlight. The state police would never note the significance of this chronology or apparently wonder how the two men found anything in the yard that night in the pitch dark.

The State Police fingerprint expert, Trooper Frank Kelly, arrived from Trenton around midnight — the same time as Lieutenant Arthur Keaten and Major Charles Schoeffel arrived to take over command of the investigation as ordered by Colonel Schwarzkopf. Lindbergh summoned Betty Gow to bring a knife to the nursery for the fingerprint expert. She later testified that was the first time she saw an envelope on the windowsill. She left the nursery as others gathered around the fingerprint expert.

Kelly slit open the dime-store envelope to find a ransom letter in poor English. Lindbergh swore all those present to secrecy and had an officer read the note aloud. The note demanded $50,000 in small bills (about $730,000 today) for the boy’s return and stated delivery instructions would be transmitted in two to four days. “We warn you for making anyding public or for notify the polise. The child is in gute care.”

Colonel Schwarzkopf greatly admired Lindbergh and would eagerly do whatever he could for the national hero in the biggest case by far in the agency’s history. Adhering to the warning in the ransom note was no longer possible. Police across the nation had already been notified. The State Police looked to Lindbergh for guidance on what to do next. Anne was reassured by the claim in the ransom note that her son was being cared for. It indicated the toddler was alive. The police had already observed there were no blood stains in the room — though one reporter would falsely claim otherwise. But Betty Gow had noticed something else that deepened her own anxiety. Although the toddler’s crib blanket was still pinned in place, the sheets now bore small rips where they were pinned. It looked like Charlie had been roughly pulled out by his neck or head. She feared for his safety.

Both of the Lindberghs told Joe Wolf they heard nothing unusual from the time Lindbergh got home until they discovered their son missing. The state trooper wrote down that the child was 29 inches tall. He asked Lindbergh “whether he had any suspicion as to who committed the crime or whether he could recall any incident such as strange noises or actions of his dog which was in the house that night.” His report that night summarized Lindbergh’s response: “He had no suspect nor was he able to recall anything at the time by which he might be able to fix the time of the crime.” The same was true of the Whateleys and Betty Gow — no odd noise heard by anyone in the house. Nor had their highstrung terrier ever barked until the police and reporters started arriving.

Kelly methodically went over every likely surface in the room for fingerprints. He was amazed to find none anywhere in the nursery, including the crib and the windowsill or on the ransom note. Even if the kidnappers wore gloves, some prints — primarily of Betty Gow and Anne Lindbergh — should have been left behind in the nursery. But no usable prints were found that night. One of the officers commented, “I’m damned if I don’t think somebody washed everything in that nursery before the print men got here.”

Lieutenant Louis Bornmann was sent to retrieve the ladder. It was so heavy it took him two trips to bring it into the house. Kelly found no fingerprints on it either. Amazingly, he could not even see any mud on the railings or rungs. In addition to alerting the police, Lindbergh had immediately summoned his lawyer Henry Breckinridge from New York. Henry and his wife Aida arrived around 2 a.m. after first detouring to Princeton University to ask Breckinridge’s 21-year-old stepson, Oren, to join them. Although the Breckinridges had themselves been there twice, Henry did not think he could locate the farmhouse in the pitch dark without Oren’s help navigating the countryside. Oren had heard the news of the kidnapping from the nursery over the radio but thought at first it must be a false rumor. As far as Oren knew when he left on Sunday, Anne and her son were planning to head back to her mother’s estate in Englewood on Monday morning as they had always done before.

It turned out that Henry Breckinridge would not have had much of a problem that night finding the farmhouse on his own. The Lindberghs’ property was lit up like a Christmas tree with all the lights on indoors, people milling around out in the yard with flashlights, and headlights of reporters’ cars and police vehicles parked in the long driveway. That in itself was extraordinary for the locals. Only one out of ten families in the vicinity even had electricity.

Hearst reporter Laura Vitray and several other journalists had made a beeline to Central New Jersey from Manhattan as soon as they heard the startling news bulletin. The reporters found they had open access to the Lindbergh estate. They parked in its driveway and stood in the yard peering in on the family and staff in the uncurtained living room.

Soon Detective John Fogarty, Lindbergh’s former bodyguard, arrived to assist Breckinridge. Both planned to stay at the farmhouse for as long as needed. Lindbergh turned down an offer from Princeton’s President to head a search of the nearby area with college students. He rejected, as well, the suggestion that they immediately assemble a team of bloodhounds to scour the area. Instead, in the wee hours of the morning, Lindbergh formed his own small search party composed of three officers and several volunteers.

Vitray and her colleagues were leaving the estate at about 3 a.m. when they encountered Lindbergh standing by his car. He told Vitray’s two male companions: “Boys, I rely on you to stay off the estate and not annoy me. For my part, I promise to give you a good break.” He got in his car and called out “So long” with a smile and a wave. The reporters looked at each other in surprise: “Hell, that is what you would call nonchalant.” Another added, “The Lindberghs are like that, they say. They never show any emotion, either of them.”

Lindbergh’s search party spent hours slogging through the dense, wet foliage on foot without anything to show for their efforts. Meanwhile, one of the first responders summoned a local trapper named Oscar Bush who had worked before as a deputy sheriff. Oscar was half descended from a Native American tribe and knew the backwoods better than anyone else. He arrived at the farmhouse around 4 a.m. on March 2 and made an important find: footprints under the nursery window and leading to the spot where the ladder was found.

Beneath the nursery window, Oscar spied a footprint from a woman’s shoe. Anne Lindbergh then told the police she had stopped there on her afternoon walk on March 1 to toss pebbles at the nursery window to attract Betty Gow’s attention so Betty would lift her toddler and Anne could wave to him. Outside, below the nursery, Oscar Bush found several large footprints and suggested they had been made by ribbed golf socks worn over men’s shoes. Police took a photograph of one footprint that was estimated to be about twelve inches long and four and a quarter inches wide.

Corporal Wolf issued an immediate order for troops to protect foot prints from any damage. Oscar traced additional footprints that he was inclined to believe were from two different persons. They went from the ladder through the field on the east side of the house to an abandoned dirt road called Featherbed Lane. There, the tracks ended. Featherbed Lane ran parallel to the cinder driveway to the Lindbergh estate about a hundred yards east of the house. Both the lane and the driveway could be accessed only from the road north that led to Wertsville, New Jersey. Oscar told investigators that whoever crossed the Lindberghs’ grounds in the dark had to know the property very well. “That ain’t easy.” Close by the footprints ending in Featherbed Lane were what appeared to be automobile tire tracks. Oscar told officers he thought two automobiles had been used in the kidnapping. Oscar assumed that the kidnappers would have known, as he did, that the only way to avoid the police was via the “isolated, muddy, almost impassable roads north to Neshanic.”

The Lindberghs’ nearest neighbors on the south side were the Conovers. The family reported seeing a suspicious car heading out of Featherbed Lane onto the Hopewell-Amwell Road around 6:30 or 6:45 p.m. on March 1. The driver turned off his lights as soon as the well-lit Conover house came into view, as if to avoid being seen. The incident struck the family as especially odd because the lane’s entrance was posted with a sign: “Road impassable — drive at your own risk.”

Oscar shared with police and reporters his conclusion of where the car on Featherbed Lane had headed on the night of the kidnapping:

“From the spot where those footprints headed at the Featherbed Lane, if you turn South you’re headed toward Hopewell and pretty soon, if you’ve got anything to be afraid about or to hide, you’ll be running straight into the arms of the police coming straight up from Princeton and Trenton.

If you turn north on the lane, you’ll be coming into the Wertsville Road … a dead end for getting anywhere. But you can turn off it into the Neshanic Road at Zion. And there’s no police up that way. For Neshanic is away back up in the hills, far from the police, but with good roads leading out … to Pennsylvania, to Summerville, New Jersey, or to Jersey City.

Or for that matter, you can drive on down again, through Skillman, with no one suspecting you, because you’d be headed the wrong way….”

Oscar’s sister Rebecca was also interviewed. She told a reporter: “Why don’t they ask us people up here to help them find the baby? We know every inch of the ground. We know the places the police will never find. But none of us is going to butt into other folks’ business until we’re asked. Even if we found the baby, we’d be a-scared to say so for fear we’d be suspected of stealing him and maybe thrown into jail for the rest of our lives.”

When Lindbergh returned to his estate in the early morning of March 2 after trekking through the woods to no avail, he saw reporters beginning to trample his yard. Unlike the rude attitude he often exhibited on prior occasions, he acted quite welcoming. He thanked reporters for their interest and had Elsie Whateley make sure there were ample sandwiches and coffee provided for them and the scores of state and local officers. The police had staked or boxed in the footprints and tire tracks, but efforts to maintain the integrity of the footprint evidence in the yard would quickly prove useless.

By then, Wahgoosh was barking almost nonstop. Lindbergh sent Olly Whateley to Hopewell several times to get more food. Lindbergh himself exhibited his usual huge appetite. He also readily joined in all discussions of what might have happened to the child, while his wife retreated from the invasion of her home. Three months pregnant with her second child, Anne felt disconnected from the trauma they were experiencing. It likely reminded her of a tragedy she endured at Smith when a good friend disappeared and was presumed dead: “A nightmare of reporters, papers, reports, clues, detectives, questioning.” Now, her own house was invaded night and day. Anne was “only occasionally seen wandering like a distracted ghost between the rooms.”

Yet while the details remained fresh in her mind, Anne wrote to her mother-in-law a chronology of what happened. She noted that Charles was downstairs in his study at 10 p.m. when Betty Gow announced Little Charlie was missing from his crib. Betty accused Lindbergh of perpetrating another of his pranks. “I did, until I saw his face.” Anne concluded that her son could not have been kidnapped between 9:30 p.m. and 10 p.m. because her husband was already in his study and would have seen or heard something. Any footsteps in the uncarpeted nursery directly above would have been clearly audible. Anne accepted her husband’s view that the crime had the look of professionals. Yet she knew that her own presence there on a Tuesday was by chance. She would not have stayed Monday and Tuesday night if her son did not have a cold. She assumed that the kidnappers must have closely followed their activities. It relieved Anne somewhat to consider the kidnapping well-planned. That gave her hope they were only after the money and would leave her son unharmed. Her first thought had been more dire — that it might be some “lunatic.”

When the Lindberghs were staying at their rental home a few miles south the prior spring a peeping Tom had peeked in their window. He might have been an escapee from the nearby Skillman State Village for Epileptics. A substantial percentage of the state’s diagnosed epileptics were segregated there on the mistaken belief they had incurable mental disorders. By the early 1930s, the village housed over 1200 inmates. Several of them had escaped over the past year, and not all had been caught.

Courtesy of the New Jersey State Police Museum.

The table with the medicine tray is between the two doors.

The same table and chair in the center of the room looking toward the east wall and the window to the left of the fireplace.

Courtesy of the New Jersey State Police Museum

The three-wheel “Kiddie Kar” parked in Little Charlie’s nursery

To the right of the fireplace behind the chair is the three-wheel Kiddie Kar State Trooper Joe Wolf described seeing on the night of March 1, 1932. To its right is the dresser, suitcase and roof of Noah’s ark against the east wall beneath the sill where the ransom envelope was left.

https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/Antique-KIDDIE-KAR-Trike-Scooter-Toy-By-H-C-White-Company-U-S-A-Patent-1918-/22347500324

Both images courtesy of the New Jersey State Police Museum

Close up of the window to the right of the fireplace with a small dresser and suitcase under it and the roof of Noah’s ark on the suitcase. Sitting on the sill is a stein. All appeared as they were when the nanny left the room at 7:50 p.m. The envelope with the ransom note was left on this windowsill.

Courtesy of the New Jersey State Police Museum

The dime-store plain envelope and ransom note left on the windowsill March 1, 1932, first opened by the state police at midnight.