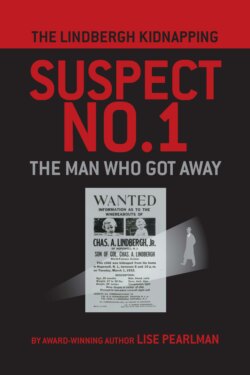

Читать книгу THE LINDBERGH KIDNAPPING SUSPECT NO. 1 - Lise Pearlman - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5.

Hooked

AT FIRST, Anne had been irritated to learn that the close-knit family’s Christmas holiday would include entertaining a famous stranger. She feared he would be boorish and put a damper on their activities. To her surprise, she found Lindbergh to be introverted. He seemed extremely young, though he was four years her senior. She noticed that he often withdrew into uncomfortable silence.

Lindbergh seemed instantly drawn to Elisabeth’s beauty and vivacious personality. Anne wondered why it was that good-looking men inspired her older sister to perform “at her best and always … put me at my worst?” Whenever the Morrows and their guest went out in public, Anne observed that Lindbergh left everyone he met spellbound. She assumed he either symbolized “the most stupendous achievement of our age” or simply exuded “personal magnetism.”

Soon Evangeline Lindbergh arrived from Detroit via San Antonio with great fanfare — transported to Mexico City in a Ford passenger plane flanked by five smaller planes for escort. The Morrow family greeted her at Valbuena Airport with a huge crowd that had gathered to watch the planes descend. Anne recorded in her diary how thrilled she was at the sight — “the tremendous excitement as of a strong electric current going through you.” Photographers and reporters also mobbed the embassy on their return, shouting “Viva Lindbergh.” Anne confided to her diary, “I can see how they all worship him.”

Anne felt tongue-tied. She envied her older sister’s conversational skill. During his stay, Lindbergh offered Elisabeth a ride in the three-engine Ford plane that had brought his mother to Mexico City. He extended the invitation to Connie and Anne, his mother, their Aunt Alice Morrow and a Ford engineer. The plane could seat them all strapped into wicker chairs in the cabin.

Arriving at the airport, Anne found the very sound of airplane motors “intoxicating.” All three Morrow daughters found their modern magic carpet ride thrilling beyond belief. Lindbergh was so sure of himself and relaxed in the air. The lift-off left Anne breathless. She told her diary: “I will not be happy till it happens again.” Elisabeth asked him at lunch if they could all learn to fly, and he encouraged them to get lessons. When Lindbergh departed on December 28 for a goodwill tour of South America, he left the family in awe. Anne later acknowledged that meeting Lindbergh completely altered “my world, my feelings about life and myself.” She now felt that the sky was something open to her to possess as well, like a soaring bird or a winged unicorn.

When contemplating graduation from high school, Anne had fantasized about marrying a hero. Long after Lindbergh departed, she still felt his glow. Despite knowing she was his intellectual superior and far more sophisticated, Anne found herself magnetically attracted to him. Anne felt she had touched greatness. She thought he exuded “clean-cut freshness … complete absence of falseness … tolerant good humor.” She was beguiled by “his smile, his attitude hands in pocket looking straight at you.” At the same time, Anne realized Lindbergh barely noticed her. Being realistic, she expected him to remain utterly inaccessible to someone like herself.

Anne soon learned that her father had invited Colonel Lindbergh to join the family again that summer at their vacation home on the island of North Haven, Maine. There, the family and guests relaxed each summer swimming, sailing, and playing golf and tennis. Anne excelled at swimming and tennis. Their estate in New Jersey also boasted a tennis court and pool, but North Haven provided a much-needed respite for Dwight Morrow away from the intensity of Wall Street. Anne envied Elisabeth. She pictured yet another handsome young man falling under her sister’s spell, while Anne stood by like a wall flower. Lindbergh was attracted to Elisabeth’s “sparkling vivacity,” while he barely noticed her younger sister Anne.

In the spring of 1928, Lindbergh made more headlines that Anne followed with fascination. While finishing up at Smith, she dated college boys who seemed all too commonplace. She resumed her focus in her last semester on classical literature and poetry, a concentration she disparaged as “utterly worthless compared to the world of Elisabeth and Colonel Lindbergh.” Yet an essay and a highly imaginative story she polished that spring won Anne two coveted literary prizes.

Late in March Anne found herself at the movies in Northampton enthralled by the documentary, “Forty Thousand Miles with Colonel Lindbergh.” It amazed her that she had met the hero of that film. On the way to the American Embassy in Mexico City, Anne and her mother got off the train in St. Louis in hopes of seeing the new Lindbergh exhibit at the Jefferson Memorial Museum, but they arrived too late for entry.

Anne kept thinking about Lindbergh. He was clearly someone from a different planet. “It is so idiotic to sentimentalize him, to see into his personality things we want to see there — things which could never, never be there. Everyone has made that mistake: he has been made a kind of slop bowl for everyone’s personal dreams and ideals.” Yet she did not heed her own warning. Soon, Anne was exclaiming to her diary that Lindbergh was “the last of the gods.”

On her way back from Mexico to Smith, Anne studied the handbook, Airmen and Aircraft. Though she had played basketball in high school, she did not believe she had the physical endurance and coordination the book considered indispensable for pilots. She credited herself with excellent vision, but it dismayed her to read that an ideal pilot should have other attributes she considered herself to lack: fearlessness,” “level-headedness at all times,” and “adaptability.”

In her spare time Anne got her license to drive and fantasized about flying again. She pored over issues of “Popular Aviation” and even wrote a few poems on the subject. In April, Anne and a friend stopped by an airfield near Smith College where Anne peppered an affable pilot with questions and wangled an invitation to sit at a parked plane’s controls so she could try them herself. In early May, Anne talked her friend into going back. Despite heavy winds, a pilot took them up on a bumpy and noisy ride, but as they flew over the college, local hills, fields and neighborhoods, Anne “felt like God.” It was “a shock of revelation, as if one suddenly saw the world upside down.” Anne went up with a pilot twice more that spring, once joined by her sister Elisabeth.

Meanwhile, Lindbergh continued making front page news with his exploits, dodging reporters ever eager to track his moves. Anne read voraciously any news she could get of him, but still dreaded his visit that summer. She could tell that both her sisters had appealed to him more. She even imagined him marrying Connie in a few years’ time, if he did not propose to Elisabeth.

In late April 1928, Lindbergh made banner headlines flying to Quebec through a snowstorm with a potentially life-saving antibiotic serum for rival pilot, Floyd Bennett. Bennett had been on his own rescue mission when he came down with a severe case of pneumonia in mid-flight, causing his hospitalization. Racing to Bennett’s aid was just the type of high-risk, high-reward challenge Lindbergh thrived on. Only he could potentially make it in time — and there was some irony involved. Bennett had been favored, along with Commador Richard Byrd, to win the Orteig Prize in 1927 but got sidelined with a serious injury during a practice flight, leaving the field open to Lindbergh.

Lindbergh’s courageous rescue mission deeply impressed Anne, though the medicine arrived too late to make a difference. In May, her idol flew from St. Louis to New York, but created the heart-stopping headline “Lindbergh Missing” after he failed to check in on arrival. The aviator was presumed dead, like so many hapless pilots before him, until he turned up and mocked the fake news he had engendered. Anticipating Lindbergh’s next visit at the Morrows’ new summer home, Anne fantasized about him once more, telling her diary it might be “sentimental hero-worship” but he was “the finest man I ever met.” Yet she considered him “someone utterly opposite to me” and clearly outside of her world.

Lindbergh’s schedule proved too busy to join the Morrow family in Maine. Then Anne learned from her aunt that he still planned to see Elisabeth that fall in New York. She concluded his marriage to Elisabeth was “inevitable.” Anne confided to her diary: “That dream is peacefully dead — speedy burial advised.” She and her sister Connie started speculating about who would come to Elisabeth’s elaborate wedding.

If Lindbergh had tried to woo Elisabeth Morrow that fall, he likely would have faced a surprising rebuff. Earlier that year Elisabeth had made a pact with her close friend from Smith, Connie Chilton, to love each other and no one else. The two made plans to start a preschool together in Englewood, New Jersey. Her parents feared the young women had begun a lesbian relationship. The Morrows did their best to keep the pair apart. In September 1928, Elisabeth left on a trip to Europe.

Meanwhile, on Henry Breckinridge’s advice, Lindbergh accepted a job at Pan American Airways and a position as technical advisor and board member at Transcontinental Air Transport, which later became Trans World Airlines. In exasperation at how much the media dogged his every move, Lindbergh told a colleague: “I’m going to quit! I’ll go out of my mind if they don’t stop pushing me.” He completed his farewell tour in the Spirit of St. Louis with a flight from St. Louis to the nation’s capital and returned to Manhattan where he often stayed with Breckinridge between travels.

Breckinridge was then newly married to his second wife, Aida, who was also an aviation pioneer of sorts. As a teenager in 1903 she took a few flying lessons from inventor and aviation pioneer Alberto Santos-Dumont and made a short hop on her own in his dirigible — the first woman in the world to fly solo in a powered aircraft. (It was a brief adventure. Aida accidentally landed it in the middle of a French polo match.)

The Breckinridges provided a welcome refuge from paparazzi and fans. Lindbergh now intended to move forward with marriage plans. Meanwhile, at Dwight Morrow’s urging, Lindbergh ventured into politics. On October 3, 1928, the pilot endorsed Herbert Hoover for President. That same day, Lindbergh called the Morrows’ home in Englewood and asked for Mr. or Mrs. Morrow or Elisabeth. Lindbergh learned that Elisabeth had gone to Europe, but that Anne was expected home later that night. He called back the next day and offered to make good on a flying lesson. Anne put him off because she was scheduled for minor surgery. The following week when they met up, her excitement diminished when the first thing he asked her was when Elisabeth would return from her trip overseas. Anne was his clear second choice. Lindbergh wanted to avoid the press, so they agreed to a late morning rendezvous at the apartment house in Manhattan of a close colleague of Anne’s father. Anne assumed they would grab sandwiches before heading out to Long Island in his new car to board his plane. She had dressed for the open cockpit flight in her mother’s raincoat, an old wool top of her mother’s, her sister Connie’s riding pants, and her father’s golf socks incongruously stuffed into high-heeled shoes. She carried a leather jacket in case she needed it in the open-air cockpit and apologized to Lindbergh for not wearing boots. Anne was both surprised and painfully embarrassed when Lindbergh brought her first to the Guggenheim mansion for an elaborate luncheon. All the other women showed up in high fashion. Before entering, Anne put on her smarter-looking red leather jacket instead of her raincoat. She proceeded to swelter through the unexpected ordeal.

The Guggenheim estate had its own landing field where Lindbergh said he would pick her up. Lindbergh then departed for Roosevelt Airfield to fetch his biplane. During his absence, the Guggenheims shocked Anne with stories of the stunts he had pulled on them while staying as their guest. One of his favorites was when they went canoeing. He would tip the canoe over to watch them get drenched and scramble for shore. Between the army and barnstorming, Lindbergh had developed a large repertoire of practical jokes he could not resist playing on anyone he spent significant time with.

Whatever misgivings Anne had about Lindbergh’s immaturity went by the wayside when he came back with a helmet and pair of goggles for her to don for their aerial tour of the city and parts of New Jersey. He also showed her how to use a parachute in the unlikelihood they had to ditch the plane. Lindbergh then tested her ability to subordinate herself unquestioningly to his will. Once safely airborne, he instructed the petrified neophyte to take the wheel temporarily, assuring her it was safe. Despite her fright, she obliged. Anne pushed herself well beyond her comfort zone to do whatever he commanded.

Anne was soon writing to her sister Connie about the flying lessons but did not tell Elisabeth or their parents. Elisabeth was still in London, having taken to bed with recurrent pneumonia. Her mother had already heard about Anne being with Lindbergh at the Guggenheims and warned Anne that her father would not appreciate seeing her name turn up in newspaper gossip columns. Despite her excitement, Anne herself had developed major reservations about Lindbergh as a suitor. She considered him “terribly young and crude in many small ways.”

While her parents remained in Mexico City, Anne and Charles visited the new family mansion, “Next Day Hill,” in Englewood, New Jersey, under the watchful eye of the housekeeper. Lindbergh suggested that he and Anne take a drive through the local countryside. Anne later wrote a fictionalized account of a couple very much like herself and Charles on a similar driving date. The young man was also considered a “great catch,” but terrible at small talk. Once he parked the car, he gave his date a lecture on carbon monoxide poisoning and then suddenly made “an awkward lunge across the front seat and blurt[ed] out a proposal of marriage. Astonished at winning such a prized beau, she accepts.”

To escape for time alone together during their stay in Mexico with her family in the fall of 1928, Anne and Charles would disguise themselves and slip out a servants’ entrance to avoid reporters. Despite how exhilarating it felt to be engaged to “the Prince of the air,” Anne vacillated over her decision during the next couple of months. She sometimes felt there was a “hideous chasm” between her world and his.

By the end of the year Anne informed her parents she had agreed to marry Lindbergh. The Morrows were, by then, less than thrilled with the prospect. The Morrows were sophisticated and worldly-wise. Dwight Morrow was highly educated and read voraciously. He enjoyed stimulating conversations about politics and was partial to alcohol. Lindbergh was a college drop-out, poorly informed, but opinionated. He was also a teetotaler with a puerile sense of humor and few manners. When the family went canoeing, he would pull the same trick he had pulled on both the Guggenheims and Breckinridges. Anne found it tiresome.

Lindbergh’s later claim that his choice of Anne Morrow to marry and bear his children was a product of careful study of her heredity did not match even cursory knowledge of her family’s health history. Certainly, by the fall of 1928 he figured out that Anne was a sturdier choice for having children than Elisabeth. Elisabeth’s slow convalescence from a second serious bout with pneumonia had the family quite worried. Lindbergh likely learned from Anne that Elisabeth had rheumatic fever as a child that left her with a heart murmur. Nor was her father a strong physical specimen. He stood under five-feet-five inches tall, suffered from chronic migraines, bouts of depression and digestive problems, and had one deformed arm.

As a teetotaler, Lindbergh also must have noticed Dwight Morrow’s chronic drinking problem. Anne’s mother, Elizabeth Cutter Morrow, was smart and industrious, but also prone to ailments. She was a twin, whose sister died as a child of tuberculosis. Elizabeth Morrow had another sister with severe developmental disabilities. Dwight Jr., the only son, had also been frail and sickly as a child. Some thought him manic-depressive. He had already been hospitalized several times. When Lindbergh met the young man, he stuttered, was subject to major mood swings and claimed to hear voices. He would collapse in a nervous breakdown in early 1928.

It seems obvious that Lindbergh decided to marry Anne despite her family’s many health problems. He was a man of action with no real interest in courtship. Having been handed a golden opportunity to marry into a highly influential family, his primary concern was a spouse healthy enough to bear him the twelve offspring he envisioned, and so besotted and enthralled with him and with flying, that she would dutifully follow his every command.

Dwight Morrow asked Anne what she really knew about his background. He and his wife had courted for ten years before they married. At the time Anne was deaf to their concerns and overwhelmed by “merciless exposure” to the media. She later realized the unreality of it all made it extremely difficult for her to acquaint herself with “this stranger well enough to be sure I wanted to marry him.” Yet when explaining to her younger sister Connie why she resolved all doubts in favor of marrying Charles, she confided, “Can’t look in his eyes and do anything else.” Anne’s diaries from Christmas 1927 until their wedding in May 1929 revealed she was “besotted with physical desire” — a “powerful sexual attraction” for America’s hero she could not resist had she wanted to. From the first time Anne shared the cockpit alone with the fearless pilot, the danger and excitement of flight acted like “an aphrodisiac.”

That spring of 1929 Lindbergh took Anne on one of several flights to picnic in private in the Mexican countryside and lost a wheel in the rough terrain. He flew around for several hours to ensure that too little fuel remained to cause the plane to explode on impact when it landed back in Mexico City. The plane did roll over but did not catch fire. Lindbergh told their rescuers it was only a slight “mishap.” Anne did not answer how she felt about it, but let her fiancé speak for her. He had already warned her against speaking honestly to interviewers, or even sharing her misgivings with those in their inner circle. He insisted that she also refrain from writing anything down that she would not want to go public.

Though Anne felt smothered, she ceased writing a diary for the next three years and self-censored her letters to friends and family. One biographer noted, “From now on Charles would be her voice.” Lindbergh got Anne to fly with him again three days after their crash landing in Mexico City. He wanted to prove how safe they felt in the air. She honored his ban on expressing any contrary view, but she later wrote about similar harrowing experiences that each time left her vowing never to do it again.

In late April, as newspapers covered closely Anne’s return by train from Mexico, the Morrows were preoccupied with her sister Connie’s welfare — an incident that would become of interest again when Little Charlie disappeared. Connie went down to Mexico on her spring break and then returned to her boarding school in Milton, Massachusetts. On her return, she received a letter from an extortionist that warned she could wind up dead unless her father paid $50,000. The anonymous letter included reference to a Smith student who had recently gone missing (someone Anne knew). It also mentioned Anne and her mother’s return from Mexico, which led police to suspect someone quite familiar with the family. The letter included a demand the police not be notified. Connie told her father, who summoned Connie home while he turned the letter over to the Milton police for investigation.

A follow-up letter in mid-May gave specific instructions where to leave the money in a crevice of a wall bordering an estate near the Milton boarding school. By then, all three of Connie’s siblings had been apprised of the threat, as well as Anne’s fiancé. Lindbergh gallantly offered to whisk his future sister-in-law in his plane to the family vacation home in Maine as a safe hideaway. Meanwhile, a young actress attended the school in Connie’s stead. A box filled with paper instead of money was delivered to the designated drop-off spot. The Milton police kept the site under surveillance, but no one ever claimed the fake extortion payment. The police requested writing samples from the Morrows’ circle of friends for purposes of comparison, but never found out who threatened Constance.

* * *

Despite repeated inquiries, the family kept the wedding date secret. At the groom’s insistence, there would only be twenty guests. Given the Morrows’ social standing they had likely wanted to invite hundreds. (When Connie had a coming out party in 1932, there were a thousand guests.) During the couple’s short engagement, Lindbergh battled his prospective mother-in-law over the size and other details of the wedding, including his opposition to having a minister officiate. Anne surprised her parents by agreeing with her fiancé. Mrs. Morrow wrote in her diary: “He has her. And we have lost her.”

Source: wikimedia.com

Lindbergh’s lawyer and close advisor Henry Breckinridge

Source: Library of Congress

Henry’s second wife, Aida de Acosta Breckinridge

Source: Library of Congress

Charles and Anne Lindbergh America’s Royal Couple. Photo taken in the summer of 1929 shortly after their marriage.