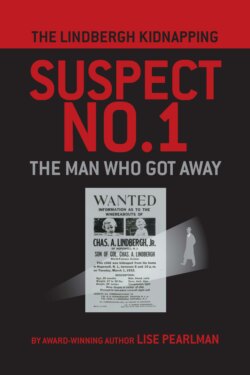

Читать книгу THE LINDBERGH KIDNAPPING SUSPECT NO. 1 - Lise Pearlman - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление9.

Getting Reacquainted with “Hi” and “Mum Mum”

ACHAUFFEUR drove Mrs. Morrow and her daughter Elisabeth up to Maine to bring Betty and Little Charlie back to Englewood. Left alone with Betty for a month, the toddler clung to his nanny, and she doted on him. While in Maine, she had his hair trimmed slightly and purchased a new outfit for him out of her wages. (No one had left her money for out-of-pocket expenses.) She was thrilled when his first word was “Betty.” Anne would not be.

Following her husband’s sudden death, Mrs. Morrow found great solace in being reunited with her grandson. When Anne and Charles arrived back at Englewood, a noticeable gloom pervaded the formerly happy household. Anne was still in shock and just beginning to grieve for her father, deepening her emotional reaction to seeing her son again. After being left behind by his parents for almost three months, Charlie did not recognize them. He cried when they approached, as he did with any stranger.

Upon returning from the Far East, Lindbergh was not happy that photographs of his son had been taken during the couple’s absence. He immediately forbade any new pictures of his son, whose blond curls still partially obscured the size of his head. Starting at the end of October 1931, Lindbergh took steps to ensure no new photos of the Little Eaglet would be released to the press by the family.

From time to time, Anne had confided in letters to her mother-in-law concerns about her husband’s ambivalence toward their son. In the spring of 1931 Anne had described Charles taking the baby and squeezing him around the neck, perhaps playfully, but her choice of wording was ambiguous: “He smiles and holds out his hands … and then strangles him affectionately.”

As the Lindberghs settled back into their spacious quarters at the Morrow mansion that November, Anne was pleasantly surprised that her husband now took more interest in the boy. He fed him some toast with jam from his own plate, swung him “ceiling flying” and nicknamed him “Buster.” Charlie called his father “Hi.” The little boy enjoyed being swung in the air and asked his father to do it “den!” (“Again!”). Yet others noted that Lindbergh bestowed another, far less endearing nickname on his son — “It.” Someone on the Morrow staff leaked to reporters that the little boy began repeating “It” among his very first new words after his father’s return.

The Lindberghs could not wait to resettle in their secluded new home. Most of the work getting it ready for occupation had been done while they were on their trip to Asia. While it was under construction, a local man named Lee Hurley had been hired to watch over the property to prevent theft of building materials and supplies. Anne was especially concerned about how they would keep the public out of their property after the house was finished. Her father must have known that Lindbergh was paying a local man to protect the building site. Had he still been alive when the farmhouse was completed, Dwight Morrow would have been outraged to learn that his son-in-law refused Hurley’s request to be kept on as a permanent guard.

The Lindberghs took a day trip to their new home on October 25, 1931, accompanied by Mrs. Morrow and Elisabeth. Access to the new property was difficult. Many roads were not marked; some were unpaved. For Mrs. Morrow’s chauffeur from Englewood, finding the estate north of the small town of Hopewell was hard to do even during the day. Once you got there, you had to negotiate a long snake of a driveway before reaching the farmhouse.

The $50,000 French Provincial home was not visible from the public road. Its two-and-a-half stories consisted of two, two-story wings jutting out east and west from the main part of the building. Its large basement was fitted with special wiring so Lindbergh could build a laboratory there. The house was constructed of local fieldstones finished in white cement and, as yet, had no window coverings. The half story at the top remained an unfinished attic.

The Lindberghs’ new home still had no beds, but that was soon remedied. On Halloween night, Anne, her mother and sister spent one night there with Little Charlie. Instead of having help from a nanny, Anne wanted time to bond with her son herself. But rising at 6:30 a.m. to change him and give him breakfast was not what she had in mind. She asked Elsie Whateley to get Charlie from the nursery and take care of him until Anne completed her own morning routine.

On the Sunday of their overnight stay, the family enjoyed leisure time with Little Charlie on the terrace. Anne may have already been following Dr. Van Ingen’s advice to get the boy as much sun as possible. Anne planned to fill the downstairs study with her extensive book collection. Her husband’s smaller collection, consisting mostly of scientific books, would be shelved in their bedroom. Originally, Anne had hoped to move into their new home before Thanksgiving, but it still needed painting inside. Anne thought the yard would look better with a bed of tulips by the house and put white ones in before winter hit.

Lindbergh had been home from their China trip only for a few weeks before he was off again on a two-week trip to the Caribbean for Pan-Am in mid-November. Anne declined to accompany him. She wanted to stay with her widowed mother in Englewood and reestablish a bond with her toddler without a nanny. Lindbergh agreed to give Betty Gow three-months’ leave.

There was still no way to avoid constant public scrutiny of the Lindberghs’ every move. One of the most widely read gossips of the time was syndicated columnist and radio host Walter Winchell. Two thousand newspapers around the world carried his column each day and twenty million people heard his Sunday night radio program. So, Anne must have felt acutely self-conscious when Winchell publicly announced that she must be pregnant again if she was not flying to Panama with her husband. Actually, Anne would not learn until December that she was pregnant with her second child.

Anne realized that her husband might feel otherwise, but she did not consider herself to be missing out by staying home while he flew solo to Panama. The last trip had been extraordinarily grueling, with three forced landings. She had always been close to her mother and wanted to be with the family as they grieved the loss of her father. She also delighted in seeing Charlie develop his father’s grin. It pleased her immensely to hear Charlie call for “Mum Mum,” or sometimes “Mummy,” instead of “Betty.” Anne enjoyed seeing her mother so delighted by Little Charlie as well. The little boy called his grandmother “Tee” after she had started letting him play with her golf tees.

Feeling extremely unwell by mid-November, Anne let her mother talk her into sending Little Charlie with Elisabeth to her preschool. Anne soon discovered that her concerns were amply justified. Charlie was only seventeen months old at the time — a full six months younger than any of the other preschoolers. The shy child with his baby curls was instantly viewed as an object of curiosity to the other tots. Bullied by some of the children and intimidated by others, Charlie could not defend himself from having his thick curls pulled, or from getting hit. He cried for the first few days. The school’s psychologist suggested leaving Charlie by himself in a sandbox until he developed social skills. (One would think that an unlikely way to get the toddler acclimated to playmates.) Left alone, he did much better, content to play by himself.

People across the country again began speculating about Charlie’s health. Rumors recirculated about him being traumatized in utero from “prenatal drumming of airplane motors.” Maybe some parent at Elisabeth’s day care started the rumor he was deaf. Or, perhaps, some staff member at the Morrows’ Englewood mansion. There was also speculation the reason Little Charlie did not interact with other children was because he was mute. No such diagnosis could have been made by the doctor at the Little School who checked all the children’s health once a week. Anyone who regularly interacted with the boy could tell that Charlie had an expanding vocabulary. To his mother and grandmother’s delight, he had also begun to learn to count.

Meanwhile, at the end of November, Lindbergh stopped in Florida for an airline promotional event on his way back from Panama. Coming home, he got severely delayed navigating through heavy snowstorms and an icy gale, prompting reporters to call the Morrow house with false reports that calamity must have struck. Instead, he had detoured with unannounced stops on his trip north. Lindbergh returned home in the middle of the night three days later than expected. With him he carried the mangled body of a seagull that had gotten stuck in his plane’s propeller. For some bizarre reason, he left the dead bird on the ground outside his and Anne’s bedroom window for several days before it was disposed of.

Catching up with home life in his absence, Lindbergh reacted angrily to news that his son failed to defend himself at the preschool. Like his own father, he did not want to raise a weakling. In December, Lindbergh built a large wire pen in the yard of the Morrows’ mansion. He then told Betty to dress his son warmly for the winter weather and put him in the pen with one of his toys “to fend for himself.” Charlie sat bewildered by his isolation in the cold outdoors, crying off and on for hours. Betty could not take it any longer. She went to Anne and begged her to bring the boy in. Anne turned to her, with tears in her eyes and replied with resignation, “Betty, there’s nothing we can do.”

In late December 1931, Anne’s morning sickness became compounded by food poisoning. The family spent that Christmas at the Morrows’ Englewood estate, joined by Lindbergh’s mother from Detroit. Charlie particularly enjoyed his gift from “Tee” — a wooden Noah’s Ark with dozens of animals. The toddler and his father played with it for hours that day. Again, the next day Lindbergh made a game of testing his son’s ability to name all the animals. Charlie was quite good at that, possibly surprising his father with his intellectual development.

There may have been a medical reason for Lindbergh to engage in that game with his son. If Lindbergh had learned by then that an enlarged head and unclosed fontanel could be signs of hydrocephalus, increased pressure of fluids on Charlie’s brain could begin to cause mental impairment. So, checking on his memory would be a way to test that theory.

Likely highest on Lindbergh’s list of concerns would have been whether all his children would turn out like Little Charlie. Lindbergh did not consider his firstborn an example of the fittest. Playing on the floor with his young son may also have brought back memories of the joyous days Lindbergh spent playing in the attic when he was three, before the twin horrors of nearly drowning and losing all his toys in the fire that destroyed his home.

The day after Christmas, Mrs. Morrow heard her grandson howling from the bathroom where he had been playing with his new rubber toys in the tub. Mrs. Morrow started screaming at her son-in-law, “sure that he had been ducking him ‘to test his courage.’” Betty got to the bathroom first. She told Mrs. Morrow that she found “Colonel Lindbergh laughing his head off. He saw that the baby wasn’t hurt, just frightened.” Mrs. Morrow never really trusted Lindbergh afterward.

Anne heard a different version of the bathroom incident from her husband that she reported to her mother-in-law. Evangeline had given her grandson the bath toys as a Christmas present. Anne told Evangeline that Little Charlie had accidentally slipped in the tub while playing with the new toys. But that did not account for why Lindbergh was found chortling at the child’s misery. Indeed, when interviewed many years later, Betty recalled “there was something about the Colonel — that little bit of sadism.” Neither Betty Gow, nor Mrs. Morrow had reason to know of Lindbergh’s terrifying “sink or swim” lesson at threeand-a-half from his own father.

The Lindberghs spent New Year’s Eve at their new home with his mother, Betty Gow and the Whateleys. By then Little Charlie was accustomed to “Elthie” as one of his caregivers. It was Betty’s first trip to the isolated property, and she dreaded it. Once the family moved for good, gone would be her daily interaction with a score of other staff. Her new boyfriend would be upset, too. She would be stuck two hours away from him in the middle of nowhere.

As much as Evangeline Lindbergh enjoyed seeing her only grandson, she refrained from hugging or kissing him, something she remembered months later after it turned out to be the last time Evangeline ever saw him. To Anne, the last months of 1931 would in retrospect feel as if she were on a “swift-flowing stream … rushing headlong to the sheer drop of tragedy.”

Courtesy of the New Jersey State Police Museum

Animals from Little Charlie’s Noah’s Ark

https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/Antique-KIDDIE-KAR-Trike-Scooter-Toy-By-H-C-White-Company-U-S-A-Patent-1918-/22347500324

Antique three-wheeled Kiddie Kar similar to the Kiddie Kar owned by Little Charlie