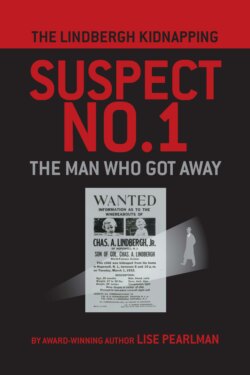

Читать книгу THE LINDBERGH KIDNAPPING SUSPECT NO. 1 - Lise Pearlman - Страница 22

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление10.

Little Charlie’s Last Days

AS THE new year began, neighbors thought the celebrated couple had not yet moved into their country estate. Mostly, Elsie and Olly Whateley stayed there alone. To alleviate the boredom, Olly gave unauthorized tours to curious fans of the celebrity newcomer. The Lindberghs still spent weekdays at the Morrows’ mansion in Englewood, but in January 1932, the Lindberghs started staying most weekends at their new home outside Hopewell. They brought Skean with them. Lindbergh called their new home “the farm,” though he had no known plans for cultivating the property. The family came down on Saturday morning and stayed just two nights. The first weekend of February Mrs. Morrow came down to the farmhouse with them. The middle two weekends of February the family stayed in Englewood because of family colds. After weekends at the farmhouse, Lindbergh’s destination on Monday mornings was Manhattan. His wife would separately pack up so Olly Whateley could drive her, Charlie and Skean back to her mother’s estate in Englewood.

That same month, Lindbergh badgered Anne to accompany him to Los Angeles to an air race show. Though three-months pregnant with her second child, she grudgingly agreed. Her husband told Anne she was self-indulgent for wanting to stay home with her toddler, and the new baby when it came. It bothered him how thrilled Anne was to see her son now mimic everything said to him.

The little boy was very sure of his likes and dislikes, which he indicated with “uh huh” and “naw.” He loved running around with the family dogs and playing with his new Christmas toys. He had his own three-wheel wooden scooter among the toys in his nursery. He enjoyed turning the crank on his music box all by himself. He also made Anne laugh when he bent over and viewed her through his legs. Charlie attended the Little School on and off through late February 1932, missing more than half of the sessions. The bullying apparently ended, and he began to enjoy the experience. Connie Chilton had noted in Little Charlie’s January 1932 evaluation that he still preferred not to interact with other children. Instead he would carefully observe what they were doing and wait until they were out of the room to repeat their activities. His report card showed “good muscular coordination,” but his “periods of concentration” were “very short,” as one would expect at a year and a half.

Writing to her mother-in-law, Anne could not help going on at length about the delight she took in everything her son said and did. He enjoyed having “Tee” and Mum Mum read and sing to him, but Tee had just left on a trip to Mexico. “Tee — all gone.” Charmed by her baby’s determination and sense of humor, and eager to share her joy in his games and laughter, she rambled on for pages until her husband intervened. This was not the first time. Lindbergh did his best to discourage his wife from writing long letters to anyone, but especially resented her recent preference for Charlie’s company to his own.

Anne had other recent occasions to sense her husband becoming quite tense. When he drove the family south for a weekend at their farmhouse outside Hopewell with the Breckinridges at the end of January 1932, their car got rear-ended by another vehicle. Lindbergh got out and banged his door shut. As he and the other driver exchanged irate accusations, Anne followed her own instincts and grabbed their toddler. Charlie noticed his father had left the car and said, “Hi — all gone.”

Movie star and newspaper columnist Will Rogers reported on his own observations. An avid flyer himself, Rogers had befriended the Lindberghs in California. He and his wife visited the family at Englewood on Sunday, February 14, 1932 — just over two weeks before the boy disappeared. In a newspaper column in early March, Rogers noted the “affection of the mother and the father and the whole Morrow family for the cute little fellow … [with] almost golden [hair] . . all in little curls.”

The Rogerses had watched Anne play with blocks on the floor with her son for an hour. Then Lindbergh repeatedly tossed a sofa pillow at his toddler while the little boy walked unsteadily in front of the adults. Each time Little Charlie got up and took a couple of steps, Lindbergh knocked his son to the floor — as if he were a carnival target. Rogers could not help but comment: “I asked Lindy if he was rehearsing him for forced landings. After about the fourth time of being knocked over he did the cutest thing. He dropped of his own accord when he saw it coming.”

Rogers might not have found the game so amusing if he knew that Charlie suffered from rickets — a Vitamin D deficiency indicative of weak muscles, easily fractured bones and skeletal deformity. The Lindberghs’ pediatrician would confirm that diagnosis later that same week. Maybe Lindbergh had kept knocking his son down so the Rogers would not notice anything odd about the boy’s gait. At the visit on February 18, Dr. Van Ingen had difficulty standing Charlie up straight for measurement at 33 inches. He also noticed that “… both little toes were slightly turned in and overlapped the next toe.” More significantly, Dr. Van Ingen noted that Charlie had an enlarged “square head.” The soft spot in the boy’s forehead would normally have closed months earlier, but Charlie’s fontanel still measured about ¾ inch in diameter. Though Charlie was tall and big-chested for his age, most other developments were far slower than Dr. Van Ingen routinely observed of twenty-month-olds. Dr. Van Ingen also noted that the boy’s skin was “unusually dry all over his body.”

Lindbergh had already begun issuing harsh commands for altering his son’s behavior. When Charlie sucked his thumb, Lindbergh ordered special thumb guards put on him at night. The thimble-shaped wire caps were attached to a string tied around each wrist. This would be part of the nightly ritual from then on. (It might have been prompted by fear that thumb-sucking was the reason a couple of canine teeth were coming in at an angle.) Because of the rickets diagnosis, Dr. Van Ingen likely warned Anne and Charles that their child was quite fragile. He likely had already prescribed strong doses of Vitamin D, a sun lamp and plenty of exposure to sunlight. Those recommendations would remain.

To prevent Little Charlie from being teased as a “sissy” or have his hair pulled again, Anne arranged to get him his first real haircut a few days after his checkup. A local hairdresser was invited to the Morrow mansion to shear off his mop of curls. The rite of passage took place in his grandmother Tee’s bedroom. Mrs. Morrow took clippings and saved them in an envelope. Very likely she also took before and after pictures despite her son-in-law’s aversion to photos of Little Charlie. The next day, Anne and her mother came to the Little School to observe Little Charlie in his rhythm class. He was obviously having a great time attempting the various moves. Mrs. Morrow left on a trip out of state on Friday, February 26, not having any idea she would never see her treasured grandson again.

That Saturday, Aida Breckinridge’s eighteen-year-old daughter Alva Root took the ferry from New York and joined Anne for lunch at the Morrows’ Englewood estate. Alva had babysat for Little Charlie before and was invited to do so this weekend as well. Her parents and brother would join them at the Lindberghs’ farmhouse. After lunch, a chauffeur from the Morrow estate drove Anne, Charlie and Alva to the new estate. Skean had somehow gone missing so they left without him. They arrived around 5:30 p.m. Anne was glad to give Betty Gow weekends off. (Betty was, too.) Alva had watched Charlie on other occasions. She and Anne set about getting him fed and put to bed at his usual 7 p.m. bedtime. The area was drenched with heavy rain driven by a chill wind.

Lindbergh spent the morning at the lab in Manhattan. Directly after lunch, he drove to Henry Breckinridge’s apartment. The timing of their friend’s arrival surprised Aida. She had understood that their plans were to leave in the late afternoon. But Lindbergh wanted to spend a couple of hours with Henry beforehand. They left New York around 4 p.m. Aida’s son Oren would make his own way to the farmhouse from Princeton where he was a student.

When Lindbergh drove the Breckinridges to the new farmhouse, Olly Whateley and Wahgoosh came out to greet them in the garage. They found Anne in the living room by a roaring fire. Aida later recalled how much Lindbergh said he enjoyed having a home in the rural countryside as opposed to the city. The couple shared some tea while Alva went upstairs to the nursery, keeping Charlie company on the floor playing with his Noah’s ark and alphabet blocks.

Anne and Aida soon came up to join Alva playing with Little Charlie in the nursery. He knew Aida as “Mimi.” It pleased her that he seemed to remember her from her visit two weeks before. Soon, Elsie Whateley arrived with his dinner, and Charlie greeted her by name as well. He delighted in his “toast” and “applesauce” and sat down to eat and drink his milk without help. Aida was impressed at how rapidly the toddler’s vocabulary was expanding. Anne then took him to wash up in his bathroom and dressed him for his evening nap in the crib with a stuffed rabbit to cuddle with. She opened a window slightly for ventilation and the two women and Alva came down to join the men for dinner.

The conversation focused on national politics. Their host seemed to be in particularly good spirits. Anne was distracted somewhat, thinking about her son’s cold. Her husband had already established a household rule that Anne was not to check on her son after he was put to bed. After dinner she looked in on him once anyway and found him sneezing a lot. She, Alva and Aida went back up at 10 p.m. Charlie remained asleep when Anne lifted him from the crib to undress him and put him on his potty seat. Aida recalled that “he woke up crying quite hard in a rather high pitch.”

After Elsie Whateley gave him some prune juice, Anne rocked him gently and sang him a favorite song as he bobbed his head to the tune. Anne then put her hefty toddler back in his crib for the night. The men came up to bed at 10:30 p.m. Alva would sleep in the nanny’s room next to the nursery, and her mother and stepfather occupied a guest room at the end of the hall. Around 11 p.m. Lindbergh joined Anne in the nursery to give Charlie some nose drops. After all the lights were out, Aida and Henry were startled out of bed by what they thought were flashes of lightning. They ran from their room as the whole house experienced intermittent bursts of light. It turned out to be a practical joke. Lindbergh had a master switch set up that would operate all the lights in the entire house at once. He was toggling the switch for his own amusement to observe their frightened reaction.

When everyone else had gone back to bed, Aida went to check on her daughter and then stopped by the nursery. She adjusted the blanket and tucked the rabbit back in the crook of Charlie’s arm. He looked quite peaceful. The next morning Anne realized that Charlie had slept better that night. Perhaps the medicine had helped. Elsie took him from his crib around 7 a.m., changed and dressed him. The whole group had breakfast in the dining room together, including Charlie. He fed himself his cereal and toast and got down from his chair to go ask Elsie for more. When he returned, he chased Wahgoosh around the table while the adults finished their own breakfast.

After breakfast, Lindbergh and Henry Breckinridge disappeared for a private talk in the library. Anne got her son’s coat and hat, and she and Aida took him outside to play on the patio and get some sun. At some point Aida’s son Oren arrived from Princeton, where he was an undergraduate. Oren had spent many weekends with the Lindberghs at their rental home in Mount Rose and had been to the farmhouse outside Hopewell before.

For a good hour Charlie entertained himself poking a stick in the dirt and running up and down. He still had a runny nose and started to fuss. They went in to let him have his lunch in the nursery. Like his father, a cold did not affect his appetite. When he was ready for his nap, Lindbergh came up and adroitly administered the nose drops. Again, the little boy seemed to have no trouble sleeping.

Later in the afternoon, the women took Charlie outside again with Wahgoosh, but his cold started to make him miserable. Back inside, Alva sat with him on the floor to play marbles. Lindbergh came by and chided the women for “fussing too much” about Charlie. He told Anne to take him back upstairs and leave him by himself in the nursery. Soon, the boy seemed too quiet. When Aida went to check on him, she found that Charlie had gotten out of the nursery into the bathroom all by himself. Apparently, none of the adults realized how dangerous it was to leave a toddler unattended — six adults and a teenager in the house, and Charlie could have accidentally drowned by falling headfirst into the toilet.

Anne, Alva and Aida then joined Charlie in the nursery and held up different miniature wooden animals from Noah’s ark. He correctly named all of them — lion, tiger, giraffe, bear. Later, he got fussy again and Anne cuddled her son and sang to him. Her new favorite was the jazz song “All of Me.” Aida noticed how exhausting it had been for the three women to keep up all day with the energetic boy. For Anne, that last weekend with Charlie would be a cherished memory she replayed over and over in her mind in an attempt to replace the horrific images that chilled her to the core after his death.

That Sunday afternoon, Aida noted that their host seemed restless. From time to time, he busied himself with various odd jobs around the house. Then he and Henry went out walking the grounds late in the day huddled in further private conversation. When they returned, the two men again holed up in the library with the door shut. Henry told her that he and Lindbergh were reading. That was not likely true. Later that spring, Aida shared with Lindbergh’s mother something Henry had told her about his private discussions with Lindbergh the weekend before Charlie disappeared. Henry told Aida that Lindbergh had confided that he hated to leave Anne alone at the isolated farmhouse: “He worried that the baby might be kidnapped.” (That sudden concern for Anne’s and the baby’s security at their isolated new home apparently was not relayed to Anne; nor, as far as is known, did Lindbergh ever tell the police he harbored that fear just two days before the kidnapping. The police might have wondered why he encouraged his wife to stay at the unguarded farmhouse Monday and Tuesday nights instead of returning to her mother’s fortress in Englewood.)

At six, Anne and Aida went up to the nursery to get Charlie ready for his bath. The little boy was quite out of sorts but managed to eat the cereal and applesauce and drink the milk Elsie brought him. Anne had just put him in the crib when Charlie recognized his father’s footsteps on the stairs. He greeted his father with: “Hi! Hi! Hi!” It made the women laugh. Then Charlie hid under his covers to encourage the adults to yell “Boo” so he would pop his head out again.

Anne loved how bold and playful her son was. Aida held his head still while Anne gave Charlie nose drops for his lingering cold. Unlike when his father administered the medicine, the little boy wriggled so much the effort was mostly unsuccessful. He then snuggled under the covers with his stuffed rabbit and went right to sleep. Shortly after the adults ate dinner, the Lindberghs drove Aida, Henry and Alva to catch an evening train at Princeton Junction back to Manhattan. Oren went back to Princeton. Meanwhile, Anne sent Olly Whateley to the store for some Milk of Magnesia for Charlie, which Anne thought might make him feel better.

If Lindbergh did harbor any fears of kidnapping, it did not stop him from leaving as usual on Monday morning without even looking in on his son. Lindbergh called Anne at the farmhouse later that day to ask that Anne stay there one more night even though he would not be returning. He did not tell Anne or Olly Whateley to take any extra precautions. Without a guarded entrance to the estate, except for an excitable terrier, security was negligible. The opposite was true of the fortress-like mansion at Englewood. With any reason for concern, Anne would surely have asked Whateley to drive them back to Englewood rather than stay at the ungated farmhouse without her husband or Skean. If worried about potential kidnappers, Lindbergh should have requested her to return that night to Englewood.

On that Monday, February 29, 1932, Little Charlie stayed inside from the wet weather as his cold got worse. He remained mostly with his mother. During the day, Anne went out for a couple of walks and left her son with Elsie Whateley. With her husband gone that night, Anne kept the doors open from the master bedroom to the master bath and nursery. She checked on her son several times.

The following morning Anne saw that Charlie remained congested. Lindbergh called to suggest that, for their son’s sake, Anne should again stay at the farmhouse. He apparently made no mention of any fear of kidnappers. Lindbergh told his wife he would drive home from work to arrive in time for dinner. He gave Anne additional specific instructions regarding the baby’s care, including another dose of medicine. Sleep-deprived and under the weather herself, Anne called the Morrow mansion in mid-morning and asked to have Betty come to the farmhouse to help with Charlie. The Morrows’ butler answered the telephone and gave the message for Betty to parlor maid Violet Sharp. Sharp would later fall under police suspicion as a possible accomplice in the toddler’s kidnapping. Betty arrived around 2 p.m. in a gusty wind and heavy rain.

Anne spent most of the afternoon with her son in the living room, reading and singing to him. She went out for a short walk after Betty arrived and stood under the nursery window at one point and tossed pebbles up against the glass to attract the nanny’s attention. Betty brought Little Charlie to the window to wave at his mother. About 5:30 p.m. the toddler went looking for Betty in the kitchen. She took the little boy upstairs to his nursery, read to him and gave him some cereal at about 6 p.m., his normal dinner time.

Anne joined them in the nursery at 6:15 p.m. after her toddler had eaten. Little Charlie was still recovering from his cold. She and Betty made sure all three nursery windows were closed. They shuttered two of them, but the bolt on the pair of shutters on the east-facing window to the right of the fireplace would not lock even when both women yanked on the shutters together. It was a problem that her mother had observed on their last visit to the farmhouse the first weekend of February. Anne mentioned to Betty that the shutters would need to be fixed. They then gave the toddler nose drops and his medicine precisely as his father had instructed. Charlie disliked the medicine and spit some of it up. Somehow, they had not mastered Lindbergh’s technique of getting his son to take his medicine without fuss or spillage. Betty got him another set of night clothes to change into.

Because he had a “croupy cough” Anne suggested that the toddler’s chest be rubbed with Vick’s VapoRub ointment as Mrs. Whateley had done for him on Monday. They wrapped a flannel bandage around Charlie’s chest to keep the ointment from rubbing off on his new T-shirt and sleeper, but then decided he might not be warm enough. Betty remembered she had a flannel remnant of an old slip in her sewing pile. Anne left to fetch a needle and thread from Mrs. Whateley. When she returned, she played with her son while Betty cut the flannel and ran it through her sewing machine to make Charlie another undershirt. The nanny sewed the shoulder seam on only one side so it could be easily removed over the baby’s head. The two women then put the flannel T-shirt on Charlie. Betty then got him back into his new, store-bought undershirt. He was already diapered and had on rubber pants. Over the underwear, they dressed him again in Dr. Denton pajamas and put him in the crib.

The two women covered Charlie snugly with a sheet, two blankets and a quilt. It was already 7:30 p.m., half an hour later than the toddler usually went to bed. They knew Lindbergh wanted them to follow his instructions to a T. He usually arrived from work at about 7:45 p.m. He would expect his son to be asleep when he arrived. Betty thought the room might get too stuffy without ventilation, so she and Anne discussed opening one of the windows slightly. Anne said she normally opened the French window on the wall nearest the crib, but only after taking into account the direction of the wind. She headed downstairs as Betty unlatched the French window and opened it slightly for ventilation while the little boy slept. Betty secured its shutters again so they would not flap in the wind and turned out the light as she left.

Anne went down to her desk in the living room. Betty washed Charlie’s clothes in the bathroom next to the nursery. The nanny checked in on Charlie again around ten minutes to eight, attached the thumb guards, and used two large safety pins to secure the blanket to the mattress. She turned out the light as she left and then turned out the light in her own bedroom across the hall. Betty went downstairs with the toddler’s wet clothes to hang them to dry in the basement. On her way, she passed Anne in the living room. The nanny reported that Charlie was breathing more normally and had “gone to sleep unusually quickly.” That was the last anyone would report seeing him alive.

Source: UCLA Leon Hoage Collection

The archivist of the Leon Hoage — Lindbergh Kidnapping Collection at UCLA identified the boy on the tricycle as being Charles Lindbergh Jr. shortly before the kidnapping. (https://www.library.ucla.edu/blog/special/2011/11/04/evidence-in-the-crime-of-the-century.) If so, this photo was likely taken in January or February 1932 at the Little School (presumably by his grandmother or Aunt Elisabeth) and may be the only full-length photo of Charlie at 19–20 months. The tricycle appears to be a Colson Fairy Model No. 1, which was a popular high-end model in the 1920s and early 1930s. The boy on the trike looks about twice the height of this model’s 16 inch front wheel: Charlie’s height was 33 inches when last measured on February 18, 1932. Although this model was advertised for 3- to 4-year-olds, Charlie was very large for his age, exhibited good coordination according to his teacher, and had his own smaller, three-wheeler in his nursery. Lindbergh himself was fascinated with bikes as a child and would likely have wanted to foster similar mechanical aptitude in his son.

Colson Fairy Model No. 1, see “1920s Colson Fairy Catalogue”: https://oldbike.eu/1911-colson-fairy-ball-bearing-velocipede-model-no-1/Fairy; Children’s Vehicles Holiday Advertisement 1930, 4 https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p267401coll36/id/7002.

Little Charlie at 20 months

Pictures taken of Little Charlie presumably on Thursday, February 23, 1932, less than a week before he disappeared. These were printed in several newspapers the week after he was kidnapped. The source of these photos was not reported but was likely his grandmother, Elizabeth Morrow, who kept locks of his hair in an envelope as a souvenir of his first haircut. (The envelope with her handwritten notations and the clippings themselves are now at Yale University archives. Yale also maintains in its Anne Morrow Lindbergh collection a typed list of photos of Charles, Jr. on Charles Lindbergh’s stationery with a handwritten notation mentioning pictures taken at Englewood in February 1932).