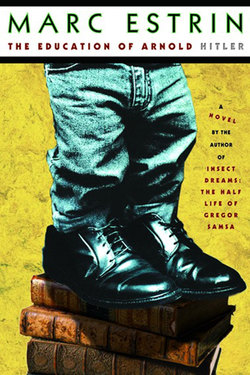

Читать книгу The Education of Arnold Hitler - Marc Estrin - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Four

ОглавлениеYou will remain in truth as long as you maneuver within its limits.

Edmond Jabès, Hand and Dial

Unlike Stephen Dedalus and his own son, Arnold’s father had a name that would fly.

George Andrew Hitler, born in 1924, grew up at a time when it was fine to be so named. Until the age of nine, his last name was neither here nor there—just another moniker, that of his own father, Tom. From nine to eighteen, the homonym was noticed by only a minority of North Texans whose newspaper reading went beyond the sports page, the funnies, the local letters and obits. And for them, it was Adolf Hitler, if anyone, who seemed the imposter, some German politician who had made off with George’s good name. Until Anna, there were no Jews around to take umbrage: in Mansfield, they knew that Bill Monroe was not Marilyn Monroe, that Floyd Jefferson, the nigger car-washer at Cluny’s Garage, was likely unrelated to Thomas, and that Adolf Hitler’s escapades could do nothing to besmirch George, a hardworking mill hand and patriotic veteran, a man who later married the woman he had wounded. Texans understood the difference.

. . .

By the time he was three, Arnold was noticing differences too, not only that between boys and girls but between his mother and everyone else. He’d become expert in helping wrap her stump and settle it into the container of her new prosthesis, in buckling it behind her right hip and helping her adjust the tension of the articulated knee. As she learned to walk, he would coach, “Kick it up, kick it up,” just as he heard the man at the hospital do when his mom was on the parallel bars. With four-and-a-half-year-old seriousness, he advised her, “The more vigorously you walk, the more resistance you will want.” She found it hilarious. He didn’t know why.

“Kick it up, kick it up,” became the secret of his success, first as a fast-running kid and later as an all-star quarterback who often had to run. There were few who could catch him, and even fewer who could stop him, so hard did he pump those long, muscular legs. In times of stress, some men think back upon their mothers. In Arnold’s case, sitting on his mama’s knee was enough to inspire his running.

His friend, Sam, was pretty smart, too—at least Arnold thought so. Especially when Sam, six, sat Arnold, five, down for a December explanation of the facts of life. At first, Arnold was incredulous. “Git outta here,” he averred. “Grownups would never do a dirty thing like that!” But Sam teased and titillated and awed and finally reasoned with him enough for Arnold to consider it a hypothesis to be checked with other kids, and, if possible, tested himself, or directly observed. His sixth birthday, then, embraced a secret “now I am a man” quality usually reserved for bar mitzvah celebrations.

Arnold was a Christmas-day child, one of a cohort famous for feeling gypped. Their birthdays have been subsumed in something so much greater than they, their annual gift quotients are generally half that of their friends, and when relative-visiting occurs, it is for Christmas dinner with a little birthday thrown in. That was why Arnold had grabbed the “nigger” demonstration as an early birthday event just for him.

His real sixth birthday proved to be quite special. Under the tree were two packages from Italy. The more obviously significant one was from Nonno Jacobo—an inexpensive but still elegant set of chess pieces with green felt bottoms, contained in a wooden box with a sliding top. With it, a hinged wooden chessboard and a set of instructions in Italian. The package said, “This is birthday present, not Christmas present.” The more subtly significant one was from Nonna Lucetta, marked, “This is Christmas present, not birthday present.” It was a child-sized Italian sailor suit, about which more anon.

It fell to Anna to teach him chess. Who else could read the instructions? They learned the moves together, and after a few weeks the family chess club was joined by George, who bought a book in English.

Anna and George were dumbfounded at Arnold’s insights. He seemed to be driving some sleek mental chess machine along a highway without a speed limit, destination unknown. Within a month of occasional games, both mother and father had given up all pretense of “letting him win.” Now each was struggling for self-respect. How could this little upstart who could barely read or spell, who got subtraction wrong, who was completely innocent of multiplication and division—how could this mere child beat the pants off them when they were trying as hard as they could to win? In February, Arnold suggested that he play both of them at the same time, first as a team, then, after he had won three games, with Anna on the chess board and George on a crayoned-in sheet of paper, using shirt cardboard cut into little chessmen.

There comes a point in every parent’s life when the subtle competition of master versus upstart gives way to frank and admiring defeat. But at age six? It was too early to concede. George, the more competitive, suggested his son play him blindfolded, a chess master’s trick he had heard about during the war. When he was soundly whupped, he upped the ante. Would Arnold play both him and Anna blindfolded?

When they each went down to defeat, they announced it was time to have a little talk. Arnold was petrified they were going to quiz him about what he knew about penises and vaginas, or even demonstrate true sexual technique to correct his childish notions. But no, they wanted him to tell how he did it, how he could always beat them though collectively they were fifty-nine years older and two hundred pounds heavier. How did he do it? This was a most unfair question for a child.

The best he could offer, with his limited abstract vocabulary and his even more limited experience at introspection, was this: “I don’t know.”

“What do you mean, you don’t know?”

“I mean I don’t know how I do it. It’s just . . . obvious.”

“What’s obvious?”

“The diagrams. The pictures on the board. I look at the pictures.”

“You mean you don’t plot out the moves, like ‘if I do this, then she’ll do that, then I’ll do this, and if she does that, then I’ll do this, but if she does that, then I’ll do this’?”

“No. I never do that. I just look at the board, and . . .”

“What about when you’re blindfolded?”

“I can still see the board in my head. Not the whole board—just the parts that matter. It’s like there’s a strain, like when I wind up my airplane, or when I have to go pee, or there’s not enough room on the sidewalk to get by—and I just see how to make it . . . not be strained. Then I move the pieces to do it.”

The answer was even more stupefying than the problem.

The second gift—the Christmas one—was more fateful. For when Arnold put on the white blouse, white pants, and white beret with the blue band, he resembled no one so much as a baby Billy Budd. Even his mother, who had read the story in Italian, felt a melting heart of recognition—followed by a shudder. The blond and handsome little sailor. The unpretentious good looks, unaffected and naturally regal. The reposeful good nature. The welkin-eyes of starry blue.

But who trifles with being Billy Budd must needs meet up with John Claggart. It’s dangerous to flirt with archetypes, to try them on to see how they look. If the fit is too easy, they cling to the skin, even after repeated washings, and they call forth scripted playmates and their consequences.

In addition, this Christmas gift from Nonna Lucetta was archetypal with glorious trimmings. On the blue hatband, embroidered in gold, for reasons stranger than fiction, was the word “CARDUCCI,” the aforementioned poet, but here a destroyer in the Italian fleet. The warship aside, the name alone would explain the gift’s attraction for the Giardinis: put such a name on the little one’s forehead and by homeopathic magic turn Arnold Hitler into a romantic genius.

What the Giardinis did not know was that in 1943 the Carducci had been enveloped in uncontrollable fire and sunk in the Mediterranean by aircraft from a new British carrier, the HMS Indomitable—the very name that, thirty feet below him, captioned Billy Budd’s last, neck-snapping dance from the yardarm. This is surely a dangerous world. “God bless Captain Vere!” With this double dose of destiny, it wasn’t long before the first of a series of Claggarts would show up to haunt Arnold-billy’s life, an ugly line of anti-beings who found him intolerable and longed for his annihilation.

“Arnold, will you write a note to Nonno Jacobo and Nonna Lucetta to thank them for your presents?”

“Can’t I just thank them through my knee? Even if only Grandpa hears, he can tell Grandma.”

“It would be fine to thank them through your knee, but I think you should also write something to show them how well you can write.”

This he did, and never wore the sailor suit but once. Bright-eyed as usual, proud, white and blue, he marched one day into class in his Carducci regalia, only to return home crestfallen and confused. Though the girls had loved it, an older boy had teased him all day about being “a fag.”

“What’s a fag?” Arnold demanded of Anna.

She didn’t know.

George: “It’s a kind of sissy. Like a boy who only wants to play with girls, play with dolls—that kind of thing. Johnny was being stupid.”

“Ah, said Anna, “finocchio.”

“I teach you something if such ever happens again. You just say to him, ‘Stick and stones can break my bones,’”—and here George joined in—“‘but names can never hurt me.’

“Can you say that?”

“Yes.”

“Say it.”

He did, putting “stick” instinctively in the plural.

“Good,” said his father, and punched him affectionately on the shoulder.