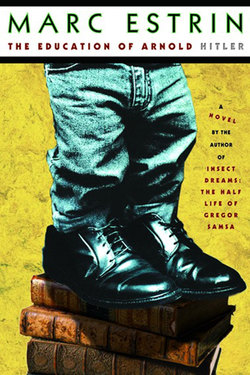

Читать книгу The Education of Arnold Hitler - Marc Estrin - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

One

Оглавление. . . because there is perhaps a song tied to childhood, which, in the bloodiest hours, can all alone defy misery and death.

Edmond Jabès, Songs for the Ogre’s Feast

Arnold’s earliest detailed memory is of being held above a crowd by his father—hard thumbs digging into his armpits—to see the cross lying there, burning on the high school lawn. It leaped and danced like huge candles at a party, just for him. In later life, he could call up the scene, fresh as ever, just by pressing his thumbs hard under his arms.

It was Thursday, August 30th, 1956. George and Anna had taken him to register for first grade, the registration to be held this year for the first time in the Mansfield High main building. But the ordeal was more difficult than they’d expected. What was going on? Where the hell were they supposed to park? Why didn’t they know this was happening?

There wasn’t a parking place up or down Broad Street within four blocks of the entrance, and citizens, some with signs, were streaming toward the school. George and Anna parked several blocks away. “What’s up?” they asked Charlie Trumbull, who was passing them hurriedly on the right.

“Three niggers think they’re gonna register this mornin,” he said, and continued his puffing trot toward the action.

“Three niggers,” Arnold said.

“Don’t say ‘nigger,’” his mother told him.

“Nigger, nigger, nigger,” Arnold said to himself.

The broad front lawn of Mansfield High was jammed with men, women, and children—all white—all milling around. There were reporters, there were cameras, there were sound-trucks. But there was little tension—at the moment it seemed more like a chance to visit neighbors, a Fourth of July picnic at the end of August. In place of the barbecue, a six-by-ten-foot wooden cross lay on the grass, burning inside a shallow firebreak. The crowd kept a respectful distance from the flames, and beefy men from the volunteer fire department stood by with fire extinguishers, making sure nothing got out of hand. “Stay back, stay back, please. We don’t want no injuries. Safety first.”

“Why don’t you stand it up?” George Hitler asked.

“Well, hell, how’re we gonna barbecue them chickens when they get here?”

George didn’t know what to make of this answer. Anna thought it was a joke. Maybe not.

Arnold had never been in such a crowd before. Fourth of July was out at the big ball field, not jammed into this kind of smaller space. His father had lifted him up, then lowered him back down. Amidst all the legs and bosoms and belts of the day, this was what he heard:

. . . here to stand together against any nigga students attempting to enroll . . .

“He said ‘nigger,’” said Arnold. But his parents didn’t hear him.

. . . not against the Negro. We think the Negroes are making great strides in improving their race and commend them for it, as long as they . . .

. . . chalkboards, typing tables, bus passes to cover their fare to Fort Worth, what the hell more they want?

. . . be like them “integrated” niggers sitting in separate rooms, sitting alone in the cafeteria after the white students finish their meal? We don’t want to do that to our niggers. . . .

“He said ‘nigger.’ Why can’t I say ‘nigger’?”

“Different people talk differently. We don’t say ‘nigger’ in this family,” George said. “We say ‘Negro.’”

We got nothin against em, but they’re being used. . . .

That NAACP may be an organization for the nigger people, but three-quarters of it is white. . . .

And Comminist!

“Daddy, what’s NAACP?”

“National Alliance for Advancing Colored People.”

Serendipitous correction from the crowd: National Association for the Agitation of Colored People is what it stands for! The National Association for the Agitation of Colored People.

“Daddy, what’s agitation?”

. . . the goddamn NAACP forcin these colored folks down here to do this. They . . .

“It’s when you stir things up and make trouble.”

“Trouble like now?”

Arnold and his parents made their way through the crowd, past the effigy hanging on the flagpole—a straw-stuffed child, head and hands painted black, overalls spattered with red paint—and under a second, similar puppet hanging by the neck from the front-door cornice. “Eeny, meeny, miny, mo,” Arnold chanted to himself. “Catch a nigger by the toe.” He was registered to begin first grade the following Monday.

His father had lifted him up under the armpits and put him down. This was his first real memory, and amidst all the legs and bosoms and belts of the day, those were the words he heard.