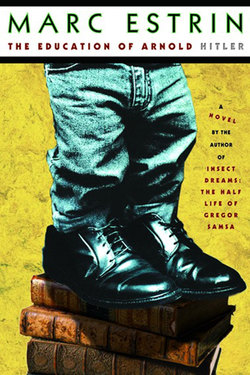

Читать книгу The Education of Arnold Hitler - Marc Estrin - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Twelve

ОглавлениеSenior year was chaotic, the zenith and the nadir of Arnold’s high school career. Preseason practice began on August 16th, in preparation for the opener on September 8th, the first Friday night of fall semester. Thirty-six boys in gym shorts and Tiger Ts gathered at Geyer Field under a blazing midafternoon sun to hear Head Coach Tommy Crews:

“Welcome, guys! You’re a good, tough-lookin bunch. You know there’s 347 boys at Mansfield High. You divide that by three, and that’s about 115 in each class.”

“Hundred and fifteen and two-thirds!” yelled Jerrod Sims.

“Sims, that slide rule’s fixin to wind up you know where.”

“Where’s that, sir?”

Snickering. Crews let it go.

“As I was saying, 115—and two-thirds—boys in each class, and here you are, thirty-six of you. That means you’re a very special breed. There are ballplayers out there who are just as good as you are, maybe better, but they’re not here now. For whatever reason, they weren’t able to stick it out, they didn’t have what it takes. You guys are special! It’s you guys who are gonna carry the torch for the ’67–’68 season. Some of you have been dreaming about bein here today since y’all were pint-size runts, and I know this is pretty special for you. If you work hard, if you pay the price, this season will be one of the great moments of your life. Be proud you’re part of this program, and keep up the Tiger tradition. What do Tigers say?”

The crew roared.

“I can’t hear you!”

They roared louder.

“I can’t hear you!”

“GGGRRRRRAAAARRRRRRH!”

“That’s better! Chuck has a couple of words for you.”

Assistant Coach Chuck Terwilliger: “Some of you boys haven’t played before, been in the spotlight. Well, I’ve got some advice for you. Have fun, hustle your ass, and stick the hell out of em. This isn’t gonna be a party. You’re gonna get hurt, and if you get hurt, that’s fine, you’re hurt. But if you get dumped, and you’re gonna lay there and whine about it, you don’t belong on the field anyway. Understand? What do Tigers say?”

While roaring half-heartedly, Arnold thought of Sammy Clayborn, who last year had lost a testicle toughing it out. No one had bothered to examine him after the game, and he hadn’t wanted to be a faggot and have some guy poking around in his pants.

“OK, guys,” Coach Crews continued, “this afternoon we’re gonna find out how hard you can play in 97 degrees. This is good practice for playing at 10 below when we go to State in December!”

A chorus of laughs and groans.

“Starting tomorrow morning, I want to see each and every one of you in the gym by 6:15 in the A.M. You know what that means? It means you’re in bed by 9—alone [knowing laughs]. It means no alcohol on weekdays—and that means you, Mahoney [more laughs]! It means you stay healthy—not for you, but for Mansfield. Understand? Today we’ll loosen up and do some playing. I want A through M over here and N through Z over here. One second. Chuck wants to say something.”

“Yeah. I just want to say that y’all notice there are nine colored boys in this room with us today. Let’s give em a hand. [Applause.] I think last year’s experience with our first colored team members was a rewarding one. They got a lot to offer, and we’re gonna treat em well. Right?”

“Right,” the boys affirmed.

“I can’t hear you, Tigers.”

“RIGHT!”

“OK, that’s it. A through M; N through Z.”

In the days before junk mail, young Texas boys never received letters, unless they wrote away to the ads in the back of comic books. But Arnold and his parents were first delighted, then shocked, then astounded at the daily arrival of recruitment letters: several apiece from Nebraska, Texas A&M, Arkansas, Notre Dame, the University of Houston, Clemson, Texas Tech, Oklahoma, Oklahoma State, LSU, SMU, UCLA. They kept arriving in slow crescendo.

Mr. Dawes, the postman, kept mental notes on all the senders and could narrate the week’s contents to Arnold, and presumably to everyone else he saw. Arnold was continually accosted by teachers, store owners, and mothers on the street: “You gonna accept Clemson? My brother went to Clemson. Loved it.” “Hey, the Aggies! That’s great. Great team. Terrific party school!” “Go, Arnie! Texas Tech. Way to go, buckeroo!”

Arnold Hitler, strong and tan, son of southwest sidewalks, being courted from as far away as Los Angeles! The siren song of foreign lands, arriving by mail in Mansfield, Texas, a rich mix of the Old South and the Wild West, where folks were friendly to a fault but fiercely independent; a God-fearing place, Mansfield, propped up by Baptist beliefs in flag and family but home to hell-raisers, always perched on the edge of violence, yet still, in some way, innocent. Arnold’s was the world of a small Texas town, isolated, insulated, a hodgepodge of junkyards and auto-supply stores, old mansions and new warehouses, all dusty and slightly seedy, a town where the four seasons of the year were football, basketball, track, and baseball but where one season dominated the rest as Christmas does the entire year. Mansfield coaches called upon the spirit of Texas individualism, plus the teamwork of the oppressed.

And now Los Angeles was calling on Mansfield for help. Our very Lady of Indiana seemed to be crying for Arnold. Because of him, the outside world was finally paying attention to Mansfield, a hitherto nowhere place where kids cruised Main and Broad on Saturday nights and teenaged honor was measured in beers. Amidst a building barrage of letters, the town anointed their annual hero as a representative, typical yet exemplary, of all the good people of Mansfield.

Arnold felt less than heroic. If anything, recently abandoned by Billie Jo, he was panicked. It was balm to his soul to take counsel with Stella Rawson.

“Mansfield? Mansfield has an awesome ability to bullshit itself. We’ve got the same proportion of assholes as anywhere. Of course we worship the football stars. There are so few things we can be really proud about. We don’t have a university, we don’t have a real library, we don’t have art museums, we don’t have theaters or concert halls. When somebody talks about Mansfield, they talk about football.”

“What are you saying, Ma?” said Edna, now sixteen and still an outcast. “It’s not that we don’t have theaters or concert halls—we don’t want them! What we want is a gladiator spectacle on Friday nights. You know what it costs to fly the team around the state? Eighty, ninety thousand a semester! Mrs. Hart, the best teacher in the school, with a master’s and twenty years’ experience, makes half of what that idiot Crews makes.”

Still, it was sweet to open the year with a forty-seven-yard touchdown pass on the first offense of the first game of the season. The fans took it as an omen of future glory, and to heighten that supposition, the Tigers treated the Highland Park Scotties to a humiliating 24-3 defeat. Arnold threw three touchdown passes and completed thirteen of fifteen others, setting off the Hitler-Frame myth of the year, the “dream duo in black and white,” proof of Mansfield’s racial sophistication.

BJ Frame was a black receiving end, six foot one like Arnold but even faster. He had starred at Terrell in his junior year and was the prize catch of Mansfield’s reluctant white fishermen. He and Arnold were not only a phenomenal team on the field over the year but they also became fast friends, the only real black-white combo at the school.

BJ began his association with Arnold with a defining act: “Hey, Mr. Doctor White Boy, I got something to show you.”

“Where’d you get this?”

“The bus station. In the black restroom. I thought you might be interested.”

Arnold examined the document, an unlined three-by-five card, neatly typed, the corners still bearing shards of scotch tape. At the top, “NOTICE,” and underneath a list of prices the white author would pay for various types of sex with Negro girls of descending age. Services would be free to any Negro woman over twenty. From there, the writer offered to pay two dollars for a nineteen-year-old, three for an eighteen-year-old, four for seventeen, etc., up to seven-fifty for a fourteen-year-old and even more for children. The card listed a contact point and urged any Negro man sitting in the stall who wanted to earn $5 to bring his friend, with proof of age.

“What’s your take on that, professor?” BJ asked.

Arnold looked him in the eye.

“You know, there’s always been plenty of nigger-lovers after the sun goes down.”

BJ nodded.

That was it. The die was cast. They understood one another beyond the words that had been spoken.

When BJ heard Arnold was applying to Harvard, he said, “Hey, man, you’ll never get into Hahvahd with that peckerwood accent. And if you get in, you better keep your trap shut for four years, or they’ll kill you up there.” There weren’t many whites in Mansfield that had an ear into the black community—and vice versa.

Thursday night was lasagna night at the Hitlers’. Jacobo had kneewise suggested a Thursday lasagna night, and Arnold was just reporting the news to his mom. Anna took these “messages” with a grain of salt. In Ferrara, when people wanted something but didn’t want to take full responsibility, they would hold up a pinky to an ear, pretend to be listening, and then announce, “My little finger says you need to give me two hundred lira for ice cream.” But how did Arnold know that when she was growing up, Thursday was lasagna day? In any case, she did need a way to celebrate her son’s celebrity and acknowledge her grudging endorsement of “American football.” So she announced that as of the very next Thursday, she would comply with Jacobo and have a Tigers’ lasagna festival every week of the season. Arnold could invite four different teammates each week, and he would see—they would all play better on Friday.

“Better than what?”

“Better than the boys that won’t have my lasagna.”

It turned out to be true. And by midseason an invitation for Hitler lasagna had become part of the stew of superstitions in which the Tigers swam. Tie a double knot in your right shoe but a single one in your left, rub your forehead with end-zone grass before each half, spit twice before a fourth down, try to get invited to Hitlers’ on Thursday, or at least eat lasagna at home.

Before the first festival evening, Arnold tacked a paper sign across the dining room: GO HANG A SALAMI! I’M A LASAGNA HOG!. He hung the half a salami that was in the fridge from the light fixture over the table. “What’s that all about?” his mother wanted to know. “C’mon, Mom, study it up,” was all he would say.

The guests arrived at 6, a group of hulking teenagers emerging from one small Nash with the combined mass of seventeen clowns. Ken Hall, center; Joe Bob Arthur, the three-first-name fullback; Darryll Ramey, 215-pound tackle—“Looks like a double portion for that one,” George whispered to Anna; and BJ Frame, the first black person to have entered the Hitler house.

“Pleased to meet you.”

“Likewise.”

“Beer?” George suggested.

“Not on weeknights,” Joe Bob explained. “Coach Crews would have our heads.”

“Dinner is served,” an accented voice announced, and the boys took seats at the table.

“In Italy, we always serve wine. Always. That’s why Italian football is better than American football.”

“Them’s fightin words, ma’am,” observed Darryll Ramey, friendly enough, but then again, you wouldn’t want to meet him in an alley.

They dug into the red-and-white helpings on their plates.

“Say, Arnold, what’s that salami doin hangin up there?” asked BJ.

“What do you think it’s doing?”

“Minds me of that effigy hangin up off the light at Broad and Main a couple of years ago. That guy Griffin, hangin there by the neck. Remember that?”

“I do,” said Arnold. “But no. It’s not Griffin.”

“Couldn’t get far enough away,” observed Joe Bob.

A whiff of racial tension sneaked across the table, which Arnold tried to disperse: “It’s not Griffin. It’s a salami. What’s salami spelled backward?”

“Imalas,” the group figured out, some checking the text on the sign.

“That’s pronounced ‘I’m a las,’” Arnold suggested.

“Hey, wait,” BJ called, “I got it. That whole sign reads the same frontways and back! Hitler, you are somethin! That’s amazing! But you know what? It still minds me of that Griffin hangin there.”

“He wasn’t ‘black like me,’” Ken Hall observed. “He was black for six weeks.”

“Well, that’s all past now,” said George. “Some of us had to be pushed, but there’s going to be integration in Mansfield, and things are already changing. Look at the team.”

BJ wanted to be polite. He had been trained to be polite. But he grabbed a teaching moment when he saw it as quickly as he grabbed a hole to run through. Fast on his feet, fast with his tongue.

“You know, Mr. Hitler, there’s integration and there’s integration. We fit as athletes, but we’re separate, still separate. Once we get off the field again? After the game? It’s like some magic change happens on Friday nights and we’re not just dumb niggers anymore. And then—back to reality.”

There was an embarrassed stillness in the room as several people silently agreed.

“There must be an angel passing over,” Anna said. “In Italy when the room suddenly is quiet, we say that.”

“If you’re strong and fast and black in Mansfield,” BJ continued, “you’re expected to do one thing and one thing only—play football.”

“Well, you people are good at that.” Joe Bob was trying to ease the subject with a compliment.

“Yup. We simple children of nature are good, unsoiled by civilization, uncompromised, uninhibited, instinctual, filled with compensatory graces—simplicity, naturalness, spontaneity, and high-grade sex.”

Arnold thought of Rousseau. The others simply thought it scary.

“You know, America may be the melting pot, but some of us got no intention to be melted.”

The angel circled the Hitler house for a long time, long enough for seconds to be passed and eaten, and apple pie à la mode—chocolate and vanilla—Anna’s low-profile symbolism. The talk turned to tomorrow’s game with Sweetwater. It had been a rich meal for all. For some, overly rich.