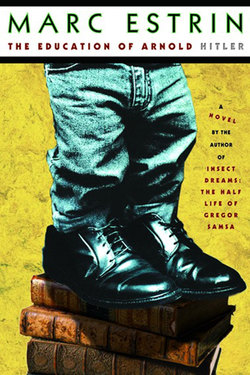

Читать книгу The Education of Arnold Hitler - Marc Estrin - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Nine

ОглавлениеTomorrow the day of the stone will break.

Edmond Jabès, Book of Yukel

High school! Emancipation (some)! Adulthood (almost)! By now Arnold Hitler was more than six feet tall and sang low tenor in the school chorus. In two years he would be able to drive. But best of all, he was the only sophomore accepted to junior varsity football, an up-and-coming Mansfield Tiger, as yet small of tooth but tall, fast, and eager.

High school football in the South, and especially in Texas, comes charged with the oversized power of a two-hundred-pound linebacker. In Mansfield, Friday night high school football was a cult, a quasi-religious experience at the very core of town life, something for Mansfield to hold on to as its children and its traditional values slipped away into the ’60s. Friday night grit, its courage, its sacrifice, mirrored in concentrated form the plight of white working-class men and women in their struggle against the encroaching forces of—everything. It was not entertainment but social self-affirmation, and the town spirit distinctly reflected each Friday’s win or loss. All this—on the padded shoulders of teenagers.

The players were up to the task. They too lived for Friday nights, and imagined themselves gladiators, Christians going up against a variety of lions, ready to bleed for the lustful shouts of a juiced-up crowd. This was their most important rite of passage, males and females alike, for the players on the team and for the golden-haired girls in short skirts and tiger-striped, patent-leather boots—the Mansfield Tiger Rebelettes—anointed to cheer them on. For these young men and women, Friday nights were a high beyond booze, beyond drugs, beyond even sex, to be equaled only by the rumored descent of the Holy Ghost into the bodies of the chosen. The season might end with a sacred pilgrimage: a trip to the high school playoffs, the most intoxicating sports event in the world, possibly to go all the way, to push on to Jerusalem itself, to “State”!

Though a decade had passed since Brown vs. Board of Education, not a single black face could be found in the hallways, classrooms, or locker rooms of alma mater. But now Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had stipulated that federal funding would not be allocated to school systems practicing discrimination, and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 had offered vastly increased federal funding to public schools operating under the integration guidelines.

There was much agony that summer at the Mansfield Independent School District. But as the Vietnamese say, “If one has money, one can even buy fairies.” And so, after eleven years of white resistance and black frustration, in the fall of 1965 thirty black teenagers were registered at Mansfield High, with no repetition of the events that had marked Arnold’s initiation into school.

But it wasn’t fairies some people in town were interested in: nine of the best black athletes were signed up to join Mansfield Tiger football, and several others were about to join the school band.

A cynic like Stella Rawson would claim that there was absolutely no social motive in the desegregation effort, that the “Big Change” in Mansfield had everything to do with percentages, how many whites, how many blacks, how much federal money, how many yards gained, how many touchdowns. There was no integration—just desegregation. Perhaps she was right. But the school district’s money grab and football strategy changed Arnold’s understanding of the world.