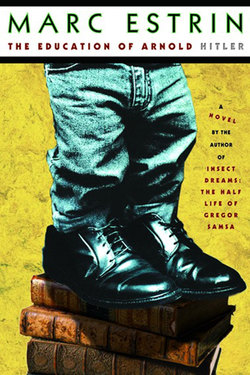

Читать книгу The Education of Arnold Hitler - Marc Estrin - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preface

ОглавлениеAll invention flows from words. We are their tributaries. They mark us as strongly as we mark them. Words for joy. Words for unhappiness. Words for indifference and hope. Words for things and for men. Words for the universe and words for nothingness.

And behind each of them, life, simple or complex, keeping its eyes on death.

—Edmond Jabès, The Book of Margins

In his Book of Practical Cats, Old Possum warned that “the naming of cats is a difficult matter” because cats require three levels of name. There are the everyday ones, low-brow to high, from Abby to Zelda, commonly parceled among the tribe. But, Eliot insists, a cat’s uncommon dignity demands better than that—some wildly uncommon name, for that cat alone: “Munkustrap,” “Jellylorum.”

Most important, however, is the cat’s Third Name, a name we can’t presume to give, and one that we’ll never know. When a cat lies eyes closed, “in profound meditation,” Eliot would have us understand that she is “engaged in a rapt contemplation” of her ineffable, “deep and inscrutable singular Name.”

We humans, too, have our common names—Marc and Donna, Mario and Hans. We may even have uncommon names: I well remember finding “Hopalong Abramowitz” in the Manhattan phonebook in the ’40s. Or we may be known by uncommon attributes, such as Edna (“the Brain”) Rawson, whom we will meet below.

But our Third Names, ah, how many of us know them? Do we know ourselves? I would submit that the goal of all education is—precisely—learning one’s Third Name.

And what would education be for someone whose second name was—Hitler? What graduation might be his? What commencement songs might be sung?