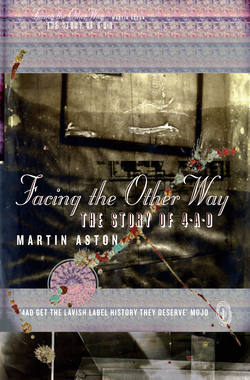

Читать книгу Facing the Other Way: The Story of 4AD - Martin Aston - Страница 13

chapter 4 – 1981 Art of Darkness

Оглавление(AD101–CAD117)

Axis had kicked into life in 1980 with four simultaneous singles, three of unknown origin. 4AD’s first complete year of operation, 1981, began in similar fashion, with three singles from two new bands, one so far unknown in the UK. Though the trio were not released on the same day, each seven-incher in its illuminating sleeve represented the same opportunity, as Ivo saw it, to ‘serve their own beautiful purpose. A record for a record’s sake.’

And much like the original Axis offensive, with the exception of Bauhaus, and much of the Presage(s) collective, none of the singles by Sort Sol, Past Seven Days and My Captains reappeared on 4AD; none were re-pressed after selling out their initial pressing, and only Sort Sol survived to release another record. These false dawns remained immaterial to Ivo: ‘The fact that a record was coming out on 4AD meant that it was a success already, which was absolutely at the heart of what I wanted to do.’

The first of the three was ‘Marble Station’, a sombre, glacial jewel by Copenhagen, Denmark’s Sort Sol (which translates as Black Sun), who had recorded two albums as The Sods before shedding its punk identity for something suitably post-punk. Ivo had heard their second album Under En Sort Sol and the band agreed to have his two favourite songs released as a single. The six-minute ‘Raindance’ by Sheffield’s Past Seven Days adopted an ominous backdrop of synths but represented a chink of light in 4AD’s assembled heart of darkness, coiled around a chattering quasi-funk rhythm guitar in the style of Factory label peer A Certain Ratio, and a matching, insistent vocal melody. The self-titled EP by Oxford quartet My Captains restored the generic setting of gloom, and was less exciting for it, while reinforcing the notion that 4AD’s core constituents might be reduced to, as the cliché had it, those shoulder-weighted interlopers in long raincoats with Camus novels under their arm.

Stylistically, all three singles were reminiscent in some form of another band from Sheffield, The Comsat Angels, which had signed to Polydor in 1979. But the Comsats’ smouldering style eventually lasted for nine albums; Sort Sol never released another track in the UK; My Captains simply vanished; and Past Seven Days were, Ivo says, ‘lured away’ to Virgin offshoot Dindisc. However, there were potential perils in joining a major label – Dindisc founder Carol Wilson once said, ‘I never signed a band unless I thought they could be commercially successful.’ Soon enough, the band asked Ivo if they could return to 4AD. ‘I was a bit of a bitch and said, no, you went away,’ he admits.

Yet just as The Birthday Party’s debut 4AD single ‘The Friend Catcher’ had followed Presage(s), so the band’s debut 4AD album Prayers On Fire swiftly counteracted the mood of short-term disappointment. The Birthday Party had started recording the album within a month of landing back in Melbourne at the tail end of 1980, and when they returned to London in March to headline The Moonlight Club (supported by My Captains), Ivo was shocked. ‘I wasn’t expecting an album, or how it sounded. Where had these Captain Beefheart influences come from?’

Cave claimed his inspiration was, ‘the major disappointments we felt when we went to England’. There was a sense of a channelled energy for one of gleeful vitriol and anger; Rowland S. Howard’s guitars humped and splintered around Cave’s brattish authority, tackling religion and morality with a drug-induced fever; as they phrased it in ‘King Ink’, this was a world of, ‘sand and soot and dust and dirt’.

Ivo may not have cared that 4AD’s releases weren’t making an indelible impression, or that the bands were often petering out, but if Bauhaus’ previous success had paid for the label’s next handful of releases, what might pay for 1981’s next batch? What he did have, finally, was a 4AD artefact that he could build into something – and how ironic that Ivo’s interest in The Birthday Party had been lit by that old-fashioned instrument, the Farfisa organ. The UK music press unreservedly embraced Prayers On Fire: ‘A celebratory, almost religious record, as in ritual, as in pray-era on fire, a combustible dervish dance, and another Great Debut of ’81,’ claimed NME’s Andy Gill.

‘The Birthday Party started to swing it for 4AD,’ says Chris Carr. ‘One by one, through word of mouth, journalists got on board.’ With John Peel already on side, Ivo recalls, ‘Birthday Party gigs started getting very well attended, very quickly. And the more frenzied audiences became, the more frenzied Nick Cave became.’

The band and singer alike were being driven on an axis of disgust, keeping itself one step removed from the UK scene the band despised. They might have been secretly impressed by the jazz/dub/punk verve of Bristol’s The Pop Group, but frequent comparisons to the Bristol band had annoyed Nick Cave so much that he studiously avoided mentioning them in interviews. He referred to Joy Division as ‘corny’, only talking up Manchester’s ratchety punks The Fall and California’s rockabilly malcontents The Cramps, whose singer Lux Interior had mastered the unhinged, confrontational performance. Mick Harvey admits he’d enjoyed Rema-Rema and Mass, but says that though he liked Bauhaus as people, ‘I just didn’t get them musically. Being preposterous was part of their charm, but Peter running around with a light under his face, I was just laughing. You couldn’t take them seriously.’

Nevertheless, The Birthday Party had a pragmatic core and set off on tour around the UK with Bauhaus in June. The Haskin brothers’ testimony to their rakish support band’s penchant for alcoholic breakfasts confirmed the Australians were willing to act out the fantasies implied by their songs, as each city and town was taken on as an enemy to be conquered. Yet in Cambridge, the support act joined the headliners for a show of solidarity during the encore of ‘Fever’.

‘It was good exposure for us,’ says Harvey. ‘Some of the audiences hated us – they just wanted to see Bauhaus – but others got us. By the end of 1981, we’d gone from playing to 300 people to 1,500. 4AD was helping on a daily basis, though not so much with funds, which Ivo didn’t have. We ran things ourselves as we’d done back home.’

But Ivo willingly offered friendship. Mick Harvey wasn’t spending his down time trying to score, unlike some other Birthday Party members, and he and his girlfriend Katy happened to live around the corner from Ivo’s west London flat in Acton, not far from the old Ealing shop, so they would periodically visit him and girlfriend, Lynnette Turner. It gave Harvey the opportunity more than most to see Ivo from a closer and more personal angle. ‘He had an underlying sensitivity that was inscrutable to me,’ Harvey recalls. ‘Australians tend to blurt stuff out, but the English tend to not let on about what they think or feel, until you get to know them well, and sometimes not even then. Ivo was very forthcoming about ideas, but you could sense something in there that bothered him, that nagged away, that he found difficult to put somewhere. The depressive tendencies, I could sense, were being covered with him getting on with everything and by his enthusiasm. He was very earnest and it was obvious how incredibly important the music was to him. It defined him.’

The Birthday Party only needed 4AD as a production house, while bands such as Modern English needed mentoring. As the youngest in a big family, perhaps Ivo enjoyed adopting the older, wiser role in a relationship, and he was far more knowledgeable about music than Modern English, even though he couldn’t play a note. But Ivo didn’t feel qualified to bring out a musicality in a band the way a producer could, and so following a Peel session for the band, he paired them with Ken Thomas, who had midwifed two Wire albums and similarly quintessential post-punk landmarks by The Au Pairs and Clock DVA.

Ivo joined the band for part of the fortnight’s session at Jacob’s residential studios in Surrey – confirming a budget beyond previous 4AD releases. He didn’t try and impose himself. ‘You got carte blanche with Ivo,’ recalls Robbie Grey. ‘He let us roll and evolve.’ Mick Conroy recalls Ivo would say what he liked and what he didn’t. ‘“Grief”, for example, sounded amazing, but apparently not at nine minutes, so he suggested we shorten and restructure it. He wasn’t a person who’d say, “Play G minor after E, play that section four times, move on to the middle eight”. But none of us were amazing musicians anyway.’

Ivo, however, thought the album had the same problem as Bauhaus’ debut; it didn’t capture the energy via the spontaneity of the Peel session. In Modern English’s case, he blames the lack of budget available to hire an engineer familiar with the studio, as he saw that Ken Thomas was unfamiliar with the mixing desk: ‘It wasn’t entirely Ken’s fault by any means,’ he adds.

Teething problems, at least at this stage, were not going to bring a band down, and in any case, the album was recorded mostly live, to keep the desired level of urgency, most notably on the opening ‘Sixteen Days’, which bravely began with an experimental stretch of guitar and sampled voices (about the only audible words were ‘atomic bomb’), and ‘A Viable Commercial’. But with four songs around the six-minute mark, more trimming would have helped, as the band’s dedication to mood building rarely led anywhere. More melodic ingenuity would have helped too: ‘Move In Light’ had the best, perhaps only true hook, to counteract the densely packed arrangements.

That The Birthday Party’s Prayers On Fire was 4AD’s first album of 1981, and it was already April, showed that Ivo – without Peter Kent’s speedy momentum – was pacing himself. But at least the finished Modern English debut album, Mesh & Lace, was scheduled for the same month. Perhaps The Birthday Party had warmed up NME writer Andy Gill, as Mesh & Lace was also favourably reviewed by him, and in the same issue as Prayers On Fire. After establishing that Modern English ‘exist in the twilight zone of Joy Division and Wire – a limbo of sorts as both bands are now effectively extinct’, he acknowledged it was ‘a worthwhile place to be … in some respects, this is the modern, English sound, Eighties dark power stung with a certain austerity’.

Gill also nailed where 4AD had positioned itself by claiming the band had ‘an edge of sincerity which sets Modern English apart from the new gloom merchants’. He summarised Mesh & Lace as, ‘not an essential album by any means, but certainly one of the more interesting offerings at the moment’, adding, ‘And if we must have groups deeply rooted in the Joy Division sound … then I’d just as soon have Modern English as any other.’

If the sound wasn’t uniquely arresting, the cover of Mesh & Lace certainly was. The full-frontal male nude tooting a long horn on the cover of Bauhaus’ In The Flat Field showed 4AD was prepared to be provocative: it’s impossible to imagine such an image in this paranoid age of sex-ploitation. Modern English’s cover star was again male, but partially clothed this time, in a kind of toga, with blurred hand movements that inferred the motion of masturbation to anyone with even a limited imagination, especially, as Robbie Grey admitted, the dangling fish ‘represented fertility’.

In a converted south-east London warehouse very near the Thames River in Greenwich where Nigel Grierson combines home and work, images that will be included in a forthcoming book of photographs line the walls. But though Grierson is also plotting a 4AD-themed book, there is no visible evidence of his role in creating the label’s visual portfolio, alongside his former partner-in-crime Vaughan Oliver.

Grierson also hails from County Durham, and was one year below Oliver at Ferryhill Grammar School. The pair had bonded over music (‘a Jonathan Richman album sealed our special friendship,’ says Grierson), literature (he introduced Oliver to the novelist Samuel Beckett; Oliver later christened his first son Beckett) and sleeve design. Grierson followed Oliver to study graphic design at Newcastle Polytechnic, where the pair bonded further over anatomy books – ‘old books, intriguing images, strange, static forms’ – and collaborated on projects. For example, a photographic series of the nude figure in nature, influenced by American photographers Bill Brandt and Wynn Bullock, but featuring the pair’s own bodies: ‘We couldn’t get any girls to pose naked!’ Grierson grins. ‘But the masculine figures gave the work another edge.’

After college, Grierson secured a work placement at album art specialists Hipgnosis, where he was mentored by co-founder Storm Thorgerson. ‘Storm was an inspiration, though he was heading in a more conceptual, less impressionistic direction than my own work was beginning to take,’ says Grierson. But while Oliver took full-time work, Grierson changed tack to a photography degree at London’s Royal College of Art; he later took a film degree but photography remained his preferred medium. At the RCA, he conceived of images ‘from the viewpoint of imagination over reproduction, more concerned with the inner world, in my head. The work Vaughan and I did was all about the “feel”, and an abstraction, reflecting the feel of the music itself. An “idea” often recedes into relative insignificance in the finished cover.’

Visual influences that Grierson and Oliver shared included vintage Polish poster design, artist – and Gilbert and Lewis collaborator – Russell Mills, and the Quay brothers Stephen and Timothy, who, Grierson feels, were ‘purveyors of the dark and intriguing’. He recalls, ‘We were a generation of people brought up on monster movies, and Hammer horror films on TV every Friday night, which I’m sure had a profound effect on our childish imaginations that manifested in the dark, macabre yet romantic feel of much of Eighties popular culture – and not just goths.’

Grierson’s approach to music took the same course, as his tastes shifted from rock to country and swing, ‘forever searching for something new’, before punk and post-punk was fully embraced, especially Siouxsie and the Banshees’ ‘Germanic atmosphere’. A few months after moving to London, Grierson had met Ivo at Oliver’s suggestion. Grierson instantly approved of 4AD’s core roster, bands like Modern English. ‘And I must have ended up seeing The Birthday Party ten times – they were the best thing I’d ever heard, so hostile and breathtaking, especially live.’

Ivo used two of Grierson’s photographs for the front and back of the Sort Sol single but the sleeve for Mesh & Lace was the first venture under a new partnership that Oliver and Grierson christened 23 Envelope. ‘It was in opposition to the egotistical way advertising agencies used a list of surnames,’ Oliver explains. ‘23 Envelope was more fun, a lyrical bit of nonsense, which also suggested a studio with a number of people and a broad palate of approaches. I didn’t want to get known for a certain style. How naïve we were!’

Mesh & Lace’s surreal composition benefited from Modern English giving Grierson the same freedom as Ivo had given the band. ‘To describe the image as sexual is too blunt,’ Grierson argues. ‘I agree the fish is a phallic suggestion, but the lace is simply feminine, and I was into [British figurative painter] Francis Bacon and movement in photos. So there’s this slightly strange context and a whole bunch of influences.’

It would have been interesting – if not a ramping up of the homo-erotica – if Oliver had managed to see through his original idea for the album’s working title, Five Sided Figure. ‘Vaughan had this drawing of a fifty-pence coin with five blokes around it with their knobs hanging out on the table,’ Mick Conroy recalls. ‘I don’t think we’d have gone with it!’

Ivo remains unconvinced by the finished cover. ‘I don’t think Nigel would argue that it worked. But 23 Envelope’s work was done on faith, and my ignorance. Vaughan and Nigel brought character and taught me how to look at things, to position things, and to contrast between fonts. But at that point, besides Modern English, all the artists 4AD worked with were doing their own artwork.’

What might 23 Envelope have imagined, for example, for the B.C. Gilbert/G. Lewis seven-inch single ‘Ends With The Sea’? The duo’s chosen seascape, the water flattened and calm at the edge of the sand, was restful but a far too literal interpretation. Just like the pair’s Cupol intro ‘Like This For Ages’, the new single was more of a song than soundscape, its nagging little melody buffeted by some electronic undertows, which converged to a mantra for the flipside ‘Hung Up To Dry While Building An Arch’.

‘Ends With The Sea’ was a reworking of ‘Anchor’ from the duo’s improvised Peel session. ‘We asked Ivo, “Can we make a single? We have this top song”,’ recalls Lewis. ‘But we couldn’t recapture it in the studio.’ This was becoming a pattern for post-punk artists, whose energies and ideas were more suited to short, sharp turnarounds, not deliberation. The single turned out to be the ex-Wire men’s 4AD swansong, as Gilbert and Lewis began a project with Mute Records’ founder Daniel Miller, and gravitated towards his label, but Ivo values their short residency at 4AD. ‘It’s easy to dismiss those works as just doodling, but they were a really important part of the freedom people had, after punk, to experiment. Bruce and Graham showed a lot of bravery.’

Mass was a classic illustration of this ingrained liberation. Peter Kent’s last task at 4AD had been to organise the band’s debut album, Labour Of Love, recorded at The Coach House studio owned by Roxy Music guitarist Phil Manzanera. ‘Mass took a very loose approach to recording and there was a lot of improvisation,’ Kent recalls. But not, it seems, to positive effect. ‘There were a couple of good tracks but overall the album was disappointing.’

‘A collection of great ideas but poorly executed,’ is Mark Cox’s similar conclusion. ‘Part was down to our attitude that we wouldn’t be produced, or let anyone in. Wally Brill, who had produced the Rema-Rema EP, took his name off it after an awful row.’

There was certainly no middle ground with Labour Of Love. Its shivering, dank and claustrophobic aura was the fulcrum of 4AD’s ‘dark and intense’ origins, a take-no-prisoners expression of borderline madness, from the opening ten-minute track’s musical embodiment of howling rain and fog. Mick Allen’s first declaration, which arrived four minutes in, was, ‘help is on its way’.

‘Mass frightened people,’ claims Chris Carr. ‘We had some press support early on from the greatcoat brigade, writers like Paul Morley, but it was too heavy for general consumption.’

Even so, the NME ignored Labour Of Love for four months, and then accused Mass of being one of the countless Joy Division imitators: ‘They parade angst, guilt and all the other seven deadly sins and just leave it at that: a charade … this album represents one emotion, one dimension, one colour, that of greyness.’

The album only struck a chord in America. Punk/new wave authority Trouser Press Guide called it: ‘dark and cacophonous, an angry, intense slab of post-punk gloom that is best left to its own (de)vices’. On its eventual CD release in 2006, the website Head Heritage claimed Labour Of Love was ‘the Holy Grail of British Post-Punk’, but also highlighted why Mass were hard to swallow: ‘… drums sounding like things being thrown downstairs, and a bitter and plaintive Cockney vocal by Michael Allen barely masking severe disappointment and contempt.’

According to Cox, ‘something dark and serious lay at our core. It wasn’t encouraging. Gary told me his relationship with Mick was often tense, and went off to Berlin and sort of didn’t come back. And Danny followed Gary.’

‘Mick and I were both stubborn, and things had started to fracture and stagnate,’ says Gary Asquith. ‘Looking back, I still held a lot of disappointment with Rema-Rema, which had been the most important stage of my sordid career so far. Mark was desperately hanging on to Mick, and it felt like time to go our separate ways, to see what happened. Berlin had a great little club scene, and I was hanging out with this all-girl group, Malaria.’

Back in London, says Cox, ‘Mick and I were still making sounds, but the energy fell apart. Mick needed to stop smoking spliff, which he eventually did. But he had a bad acid trip, which I think left a bit of a legacy.’

The night of his LSD misdemeanour, Allen had turned up at Ivo’s home, showing that even a renegade such as Allen trusted in Ivo’s company. ‘He was a strange, sometimes awkward, shy fellow,’ Allen recalls, ‘but I liked him. I saw Ivo as an older brother, and we’d talk about music in the same way, though I’d take the piss out of what he listened to! He was obviously from a certain background, and we were working class, but we connected.’

Mass’ unencumbered liberty was mirrored by 4AD’s next release, the most esoteric to date: an instrumental album, snappily titled Provisionally Entitled The Singing Fish, from a vocalist by trade – Gilbert and Lewis’ former Wire sparring partner, Colin Newman.

Newman had been raised in the thrills-free province of Newbury, 60 miles west of London, and attended art school in the marginally more engaging city of Winchester and near to the capital in Watford, which had London pretensions without its credibility. Newman thought he’d be an illustrator, but admits, ‘I wasn’t very good. I was at art school to join a band.’ After being asked to sing in an end-of-term performance by the college audio-visual technician, Bruce Gilbert, Newman had found his vocation, adding pop nous and oblique lyricism to the Wire formula.

When the band had fractured, Wire’s manager Mike Thorne had approached Martin Mills at Beggars Banquet, who used some of the Gary Numan profits to fund Newman’s album A–Z. Newman didn’t arrive at 4AD via his Wire bandmates or even Beggars, but after meeting Peter Kent at a party. Kent had, in turn, introduced Newman to Ivo, knowing they’d have much in common: both were the same age (twenty-seven), they both loved Spirit and the late British folk rock singer-songwriter Nick Drake – to Newman’s surprise, ‘as I thought nobody else knew him then’. The musical conversation had turned to an instrumental record that Newman had in mind, and Ivo was happy to have another Wire representative on board. ‘I liked Colin, and I’d loved A–Z, which to me was the great lost fourth Wire album. And I thought he would do something good again. And he did.’

On Newman’s side, Ivo felt he’d benefit from having access to the independent charts. ‘That was one of his lines,’ Newman recalls, ‘and I’m sure it was true. But that wasn’t why I made the record. I wanted to do an alternative to a “song” record.’

Newman recorded all twelve impressionistic tracks – titled ‘Fish One’ to ‘Fish 12’ – of Provisionally Entitled The Singing Fish by himself (except for ‘Fish Nine’, which featured Wire drummer Robert Gotobed). ‘It was ahead of its time,’ he feels. ‘People would later do the same with sequencers and sampler, fiddling with varispeeds, flying stuff in off different tapes, building music by layers and extemporised in the studio.’

There was an appreciation for Newman’s ‘wealth of nuance in such a stripped structure’, according to NME, in a review that concluded by noting ‘surreal dreamscapes whose icy beauty is unusually attractive’. But the only instrumental, filmic exercises that had more than a limited esoteric appeal came from former Roxy Music synth magus – and inventor of ambient music – Brian Eno. Singing Fish was too rarefied to compete.

‘It upsets me greatly that what Colin did on 4AD is written out of our history,’ says Ivo. ‘But not as upset as when it happened to Dif Juz.’

Few bands set an agenda that would be barely acknowledged at the time, and yet emulated by so many in years to come, as Dif Juz. While Colin Newman had been experimenting without voices, the London-based quartet was instrumental from the off, laying the groundwork for what became known as post-rock during the mid-Nineties, a genre that eschewed the rhythm and blues-based recycling of rock’n’roll cliché for a more striking, freeform approach. Shorn of words, Dif Juz’s only point of view was an exploratory fusion, which pinpointed 4AD’s willingness to allow artists to exist in worlds only of their own making.

The saga of Dif Juz is uniquely mesmerising if only for what came after – or what didn’t. So total is the disappearance of the band’s creative hub, guitarists and brothers Alan and David Curtis, that not even their former bandmates Richie Thomas and Gary Bromley know of their current whereabouts. Neither does the band’s music publisher, who cannot send royalty cheques without personal details. There isn’t one lead online either. When 4AD released the Dif Juz CD compilation Soundpool in 1999, a website had temporarily appeared displaying the words, ‘By us about us’ and ‘more soon’. Since Dif Juz was imbued with mystery, from its name to its sound and song titles, it all has a rational, if sad, logic.

‘David and Alan were nice people. Quiet, reclusive, and great guitarists,’ is the memory of Dif Juz bassist Gary Bromley. The last time drummer Richie Thomas saw the Curtis brothers was in 2002 at his mum’s funeral: ‘They liked my mum. Alan was working as an electrician, and they’d do painting and decorating. They were just different. Your first impression of Alan was of a university graduate, very well spoken, and an intellectual. But he was a working-class kid, like me. David was cool, edgy, interesting, a great sense of humour, amiable, but volatile too. Things could go a bit crazy if he was pushed in the wrong direction. I saw him on stage once; his guitar kept cutting out, so he kicked the amp and punched out the stage light above his head. There was glass and smoke everywhere.’

The other curious aspect to the Curtis brothers, who hailed from Birmingham in the Midlands, was that the classically trained David Curtis was even, briefly, a member of the embryonic version of New Romantic icons Duran Duran (Andy Taylor took his place in the final, famous line-up). Legend has it that Curtis vanished one night, fearing for his safety, after Duran hired local nightclub owners as their managers.

Down in London, the brothers formed the punk band London Pride. Richie Thomas saw them play at the Windsor Castle pub. ‘I told the singer, “Your drummer’s shit”. He said, “OK, give me your number”. After we rehearsed, I joined.’

Raised in the same north-west London area as the Models/Rema/Mass boys – though being younger, he only crossed paths with them years later – Thomas tells a familiar tale of glam, hard and progressive rock habits surrendering to punk. He was just thirteen when he discovered the Sex Pistols: ‘They had so much energy, and when I bought a Damned album, that was it, I was gone.’ He even customised his own clothes, which got him vilified. ‘I always felt like an outcast, with everyone having a go at me,’ he says.

The same year, Thomas began drumming for a local band, Blackout. When he joined London Pride and met the Curtis brothers, he’d hang out at the band’s squat in nearby Alperton. ‘This north London gang had been after me so I went to live there, this druggy madhouse.’ Under the influence or not, Thomas embraced the brothers’ new plans, to make instrumental music, which began with a demo of ‘Hu’ that was re-recorded for the opening track of debut Dif Juz EP Huremics. ‘It sounded completely new and tantalising,’ Thomas recalls, ‘out of the Roxy Music school, but unlike anything I’d ever heard.’

No one is sure of the origins of the band’s name Dif Juz. Was it a variation on Different Jazz? Years later, Ivo heard it was to be spoken with a soft Hispanic accent, like, ‘diffuse’. Thomas’s memory is vague, but he says everyone was stoned at the time. ‘Someone asked about our name, which we didn’t yet have. Something was suggested on the spur of the moment, and later on, someone said, “What was that name again? Was it Dif Juz?” It was onomatopoeic, and it stuck. When people said it meant “Different Jazz”, we’d go along with it.’

Gary Bromley was another admitted stoner, who had also seen London Pride and met the Curtis brothers. Bromley now lives in Louisville, Kentucky (from where his wife hails), but he was raised in west Ealing, where a strong Jamaican community had given him an early taste for reggae and marijuana. Punk was just around the corner: Bromley says he spiked and dyed his hair, and joined a band, Satty Bender And The Gay Boys: ‘Homophobic, I know, but we didn’t know better back then,’ he says. Adulthood arrived alongside post-punk, and Bromley – a regular customer at the Beggars shop – took great interest in PiL bassist Jah Wobble’s adventures in dub. ‘But only after joining Dif Juz did I take the bass seriously,’ he admits.

Dif Juz’s lack of a singer, Bromley says, ‘was down to the necessity of the situation’. According to Thomas, the band auditioned some vocalists, but says, ‘It was hopeless; too much ego going on.’ In any case, a voice would have competed with the brothers’ musical foraging. It didn’t hold Dif Juz back; at only the band’s second show, at the west London pub The Clarendon, EMI’s progressive rock imprint Harvest, which had had a rebirth, made possible by signing Wire, offered to release an album – if they’d accept a producer of the label’s choice. ‘A few labels were interested, actually,’ Thomas confirms. ‘But we didn’t think anyone else would know what to do with our music. We felt very protective of it.’

Ivo attended the following Clarendon show a month later. ‘Word had got out,’ says Thomas. ‘I’d bought “Dark Entries” and “Swans On Glass”, so I knew who 4AD were. Back then, Ivo had a little ponytail; I’d never seen a picture of Eno at that point and I imagined that Ivo was what Eno looked like! I wasn’t far off. He was arty, genuine, and very interested in us.’

Ivo: ‘Dif Juz had this husband-and-wife management, who brought me the tapes, and I really, really liked it. They were an interesting bunch. Gary had been at school with [Mass drummer] Danny Briottet, and he did the best Robert de Niro impression! He looked a bit like de Niro too.’

‘Ivo wanted us to make an album, but we didn’t want to be in debt, so we agreed on an EP, to see how things went,’ says Thomas. ‘Ivo was willing to take a chance and let us produce ourselves. The engineer said, “You can’t do that, you can’t move things around on the [mixing] desk, the EQ and faders”. I replied, “Is there a rulebook that says so?” I was adding reverb, making it quieter, and the guy started getting into it and suggested tape loops, extra echo and other effects.’

Recorded at Spaceward studio in Cambridge, ‘Hu’, ‘Re’, ‘Mi’ and ‘Cs’ made up the four-track EP Huremics, an imagined word that hinted at something indefinable, like the music, which stretched between rock, dub and ambient. Today, Dif Juz would be lauded by the tastemakers of the blogsphere, but in 1981, not even John Peel got it. ‘And as you know, you’ve got nowhere to go without Peel,’ says Ivo. ‘They never got off the ground.’

Undeterred, Dif Juz released a second EP, Vibrating Air, only months later. Thomas recalls rehearsals taking place religiously every Sunday: ‘We’d smoke pot and jam for hours, making the music we wanted to hear because no one else was.’ Recorded at Blackwing with John Fryer, who was now engineering a succession of 4AD recordings, the four new tracks were called ‘Heset’, ‘Diselt’, ‘Gunet’ and ‘Soarn’, all anagrams, spelling out These Songs Are Untitled. It was a dubbier affair than Huremics, setting it even further apart. ‘Dif Juz was ahead of its time, like so much of Ivo’s A&R,’ says Chris Carr. ‘Look at what happened to Modern English, and to Matt Johnson. Ivo went where others would eventually go. His view was, it may take time but it will flourish.’

Modern English had also been visitors at Spaceward and subsequently upped their game after Mesh & Lace with ‘Smiles And Laughter’, a sharper and sleeker single that restored Ivo’s faith: ‘The sound was again appropriate,’ he says. Yet Carr still found it hard to raise the band’s press profile. ‘Modern English were caught between two stools, on the edge of experimentation, but with a pop angle. Independent music was beginning to take off on radio, and while Daniel Miller employed radio pluggers for bands like Depeche Mode, Ivo wouldn’t do the same. He wasn’t willing to play that game. It was a judgement call, but also financial.’

Among Mute’s growing stable of synth-wielding acts, from cutting edge to pop, Depeche Mode gave the label daytime radio exposure and a profile that didn’t depend on John Peel or the music press. Ivo wasn’t even looking for pop acts, and pop acts weren’t looking for 4AD. Not that the label wasn’t a repository of great singles, such as The Birthday Party’s ‘Release The Bats’, recorded after the band had returned to London, and the perfect lurching anthem to make the most of the band’s burgeoning popularity.

The single topped the independent charts for three weeks in August. With the lyric concluding, ‘Horror bat, bite!/ Cool machine, bite!/ Sex vampire, bite!’, Nick Cave may have intended a withering parody of the goth theatrics he’d witnessed close up on tour with Bauhaus, but ‘Release The Bats’ is considered a genre classic, making number 7 (one place behind ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead’) in NME’s ‘20 Greatest Goth Tracks’ list in 2009, claiming, ‘Here was a compelling sonic template for goth’s lunatic fringe.’

A month later, in September 1981, The Birthday Party made their maiden voyage to the USA. It was literally a riot by all accounts, with interrupted and cancelled shows, blood spilt and audiences riled. According to band biographer Ian Johnston, at the band’s US debut in New York City, Cave weaved the microphone lead around a woman’s throat and screamed, ‘Express yourself’, and the next night, he repeatedly beat his head on the snare drum (both shows got cancelled). It was followed by a debut European tour and a short UK tour, where the hostility didn’t let up. Ivo was starting to have doubts. ‘The shows were very exciting but it had got too rock’n’roll for me, too grubby. I’m not interested in violence and someone on stage kicking a member of the audience in the face.’

Ivo was on more comfortable ground with 4AD’s next single, an oddity that came from a meeting between Bauhaus’ David J and René Halkett, the only surviving member of Germany’s original Bauhaus school of Modernist craft and fine arts founded in 1919. David J had recorded the octogenarian Halkett in the summer of 1980, at the latter’s cottage in Cornwall, supporting his frail voice with a cushion of electronics, upbeat on ‘Amour’, soothing on ‘Nothing’. Despite Bauhaus’ shift to Beggars Banquet, David J had stayed in contact with Ivo: ‘I told him about the project. He heard it just the once and said he’d release it on 4AD. It was where Ivo was heading with the label: off-the-wall, arty projects.’

Bauhaus’ profile would have ensured enough sales to pay for something so left-field, but as Ivo notes, ‘It was a lovely thing to do. The single could be described as dreadfully pretentious but who gives a fuck? Halkett was a nice man, and it meant a lot to him that David wanted to do this.’

Ivo’s affection for his friends, even those that had left 4AD, was clear, and delivered much more satisfaction than sales-based decisions. 4AD was growing into a little family, and Ivo recalls he felt like an older brother to Matt Johnson during the making of his debut album Burning Blue Soul. ‘I was shy and introverted, then, still a teenager,’ Johnson concurs. The relationship had strengthened when Johnson was unhappy with new demos he’d recorded with Bruce Gilbert and Graham Lewis, and had turned to Ivo, who got more involved with the recording.

As Johnson recalls, ‘I was recording a couple of tracks at a time, in different studios with different engineers and co-producers. Ivo wasn’t there for a lot of it and his role was more as an executive producer, but he became far more hands on with a couple of tracks at Spaceward [studios]. He’d suggest ideas but wasn’t precious about them. I liked that he’d test you to make sure you believed in what you were doing. If he thought differently, he’d strongly argue his case, but ultimately he’d ensure power resided with the artist. He liked working with artists who had a clear vision and self-belief and saw his role as facilitating unusual projects no other labels would take a chance on.’

Given free rein, Burning Blue Soul was raw and adventurous, with an unusual blend of bucolic British psych folk and Germany’s more fractured krautrock imprint, bearing only distant traces of the sophisticated blend of subsequent The The records. The opening instrumental ‘Red Cinders In The Sand’ was almost six minutes of ominous churning, and even calmer passages such as ‘Like A Sun Rising Through My Garden’ sounded infested with dread. Johnson’s vocals were often electronically tweaked, boosting the alienation. Johnson recalls: ‘It was considered the most psychedelic album in many years when it came out.’ (No doubt aided by the sleeve design’s heavy debt to Texan psych pioneers The 13th Floor Elevators’ album The Psychedelic Sound of …) ‘In reality,’ Johnson concludes, ‘it was almost virginal in its innocence, and unlike some albums I made afterwards, it was made on nothing stronger than orange juice.’

‘It’s an unusual record, a real mish-mash that works,’ Ivo rightly asserts. ‘Maybe Matt hates it now, but I’d like to think we had a lot of fun, in the studio and driving back and forth. Watching Matt work was fantastic; he was so fast, and he had that wonderful voice, like [Jethro Tull’s] Ian Anderson.’

Actually, Johnson reckons Burning Blue Soul still sounds great: ‘It was made for all the right reasons; I was just a teenager when I wrote and recorded it so there was not only a fair degree of post-pubescent anxiety but a real purity and unfettered creativity. I didn’t know the rules of songwriting then so I wasn’t bound by them, but I was able to put into practice a lot of the studio techniques I’d learnt at De Wolfe. It’s also the only album where I play all the instruments. So I’m proud of it.’

The post-pubescent anxiety that Johnson describes gave Burning Blue Soul a rare burst of politicised anger to match In Camera’s David Scinto ( coincidentally, both hailed from Stratford, though had different social circles). An upbringing in an East End pub would have borne witness to the volatility of crowds and Johnson says the summer riots across Britain that spring and summer, from London to Birmingham and Liverpool in protest at Margaret Thatcher’s economic squeeze on industry, employment and taxes, fed into the album’s levels of stress. Likewise the assassination attempts on the Pope and US President Ronald Reagan, specifically on ‘Song Without An Ending’.

In its own way, standing apart from all other singer-songwriter records of the time, Burning Blue Soul wasn’t much less of an oddity than Dif Juz, and with few exceptions, the UK press was very cool (and Peel again didn’t bite despite initially supporting ‘Controversial Subject’), at least to start with. ‘Ivo and I really believed in Burning Blue Soul,’ says Chris Carr. ‘And we couldn’t understand why it wasn’t clicking with people. It took six months to get a review, but when we did, that’s when The The took off, and I’d get calls from journalists asking for a copy of the album. I asked Ivo for more stock, and he said, “Fuck off, they can buy it back from Record & Tape Exchange, where they’ve sold their original copies”.’

Johnson says how much he enjoyed his time at 4AD, but another figure took control of his career in a way Ivo would have categorically avoided. The singularly named Stevo, the founder of the Some Bizzare label and a committed student of Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren’s method of major label-fleecing, had become Johnson’s manager and solicited a very sizeable offer from CBS, which was raised by competing bids by other majors. ‘There was no advance for Burning Blue Soul and no royalties for quite some time, so I was always broke,’ Johnson explains. ‘At certain times of your life, it is very hard to resist these kinds of siren calls. In some ways, I regret not staying on 4AD for another couple of albums. Ivo warned me against CBS – he said it was too soon for me to make the switch and that I could fulfil myself on 4AD. He was extremely gracious and didn’t guilt-trip me about it. I’ve no regrets as I was with CBS [which turned into Sony] for eighteen years and I was allowed a huge amount of artistic freedom, but I sometimes wonder how it would have panned out if I’d stayed with 4AD. Ivo was one of the big influences on my career.’

‘I don’t remember being disappointed,’ says Ivo. ‘I was totally committed to the idea of one-off contracts, and if someone didn’t want to be with 4AD, that was fine by me. But I wish we’d stayed in touch for longer because I really enjoyed Matt.’

Johnson: ‘One last example of Ivo’s integrity was that when I decided to change the artist title of Burning Blue Soul from Matt Johnson to The The (when the album was re-released in 1984), Ivo didn’t want to, despite the fact that it would result in more sales as it would be stacked with my other The The albums. He insisted we put a disclaimer on the cover to explain that it was my decision to change the name. Can you imagine a major label resisting selling more copies on a point of principle?’

Points of principle, however, were a mark of the times. Commerciality meant selling out; integrity and authenticity were the presiding philosophies. After playing shows with The Birthday Party and In Camera, Dance Chapter had also recorded at Spaceward, producing the prosaically named Chapter II EP, inspired by the pursuit of beliefs that eventually led Cyrus Bruton to the spiritual comfort of the Bhagwan community. Parts of Chapter II, particularly the clotted tension of the eight-minute ‘Attitudes’, matched the first Dance Chapter single. The track tackled, says Bruton, ‘how prejudices build walls, kill love and create pain, which was obvious but I felt it needed to be said in a song’. ‘Backwards Across Thresholds’ and ‘She’ addressed desire and relationships while ‘Demolished Sanctuary’ tackled the suffocation of individual needs within the crowd.

‘Punk was cathartic in the sense you could scream and jump, and out of it came a lot of creativity,’ he concludes. ‘But I felt that people needed to have more faith in their own perception, about how to find their way, in relationships, sexuality, drugs and alcohol, handling money, aspirations and rebellion. I was myself trying to find a way through the impressions and inputs. We all were.’

However, in Ivo’s mind, this struggle had manifested itself in the studio, where he’d driven to survey proceedings. ‘No one seemed in the mood, so I just left,’ he recalls. ‘I’d heard the demos, and anyone who has released records based on demos knows that proper recording can lose something. Chapter II is OK, but there was no real direction, guts or energy. So for those reasons, I started to get involved more in the studio after that. If things were going wrong, at least I’d know why.’

‘It wasn’t my impression that things weren’t going well,’ says Bruton. ‘Either way, being on the edge was part of the creative process.’ The problem was, Dance Chapter’s collective spirit was fast dissolving, over money, or the lack of, and personal ambition. ‘We were also going in different directions. Steve [Hadfield] was still studying, and he left soon after the recording. I wasn’t looking to make a career from music, though I’d have gone on. But I didn’t have a way to hold a group together, or rebuild it. Ivo suggested I move to London and see what happened, but by then, I’d reached the places I needed to go, and I had the freedom to look at things in another way.’

Dance Chapter was the first of 4AD’s artists to fall at the second fence, and again, its four constituents didn’t make inroads into other music. If the band’s demise was a downbeat conclusion to the year, there was enough achievement to end 1981 with a compilation, which Ivo assembled for the Japanese market via major label WEA Japan, which was distributing 4AD in the Far East. Housed in a photo of two wrestling male nudes from one of Vaughan Oliver’s medical journals, Natures Mortes – Still Lives was a personal inventory of 4AD highlights, including the early Birthday Party single ‘Mr Clarinet’ that Ivo had reissued on 4AD, and tracks from Rema-Rema, Modern English, Matt Johnson, Mass, Sort Sol, In Camera, Cupol, Past Seven Days, Psychotik Tanks and Dif Juz. Gathered in isolation, 4AD’s formative years sound distinctive, predominantly original and, with hindsight, undervalued, though only in light of what was to follow.

In a letter to the American fanzine The Offense towards the end of 1981, Ivo said he thought he was ‘moving away from rock music, even in its broadest sense, as much as possible’. There was even talk of Aboriginal chants. He concluded, ‘I’m confident of change and a very valid and varied output – but my search for something far removed from anything I’ve ever done will continue.’

Ivo already had something in mind that fulfilled that brief. Driving back home from Spaceward after abandoning the Dance Chapter session, he stuck on a demo that he’d been given at the Beggars shop that week. ‘I got called upstairs and whoever was behind the counter said, that’s Ivo, and this cassette got stuffed into my sweaty hand,’ he recalls. ‘Something was quietly said, and the couple left. When I listened, I immediately enjoyed it. It sounded familiar, like the Banshees, though with a drum machine. And a voice you could barely hear. There was no indication that she was great or bad. But the power of the music made me call them to suggest they make a single.’

When Ivo called, he discovered his visitors that day, guitarist Robin Guthrie and vocalist Elizabeth Fraser, had come down from Grangemouth in Scotland to see The Birthday Party. ‘We first saw The Birthday Party open for Bauhaus, and we started to follow them around on tour,’ recalls Guthrie. ‘We were just teenagers, and painfully shy, but we started talking to them after shows. Eventually they said, are you in a band? Yeah, we said. They said they’d met these people in London – which was 4AD.’

Nothing would be the same for 4AD after Cocteau Twins.