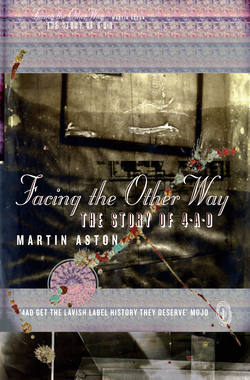

Читать книгу Facing the Other Way: The Story of 4AD - Martin Aston - Страница 14

chapter 5 – 1982 The Other Otherness

Оглавление(CAD201–AD215)

Sorry for the delayed reply. I’ve been somewhat affected, in a truly depressed sort of a way since you came here. Not your fault, buddy, just a barrel load of worms wriggling about in my consciousness which I’m not dealing with too well. Apart from that, well, I’m OK.

Someone much wiser than me once told me that I had to make peace with my past in order to enjoy the present, but what if one’s past becomes one’s present.

And that, my friend, is where I am at.

Worms, Can, Opened.

(Robin Guthrie, email, July 2012)

Rennes, to the east of north-west France in the region of Brittany, is an hour by plane from the southern tip of England. It’s where Robin Guthrie met his French wife, but it’s a convenient location, near enough to keep in touch with his past, far enough to keep out of reach.

Fifteen minutes’ drive from Rennes city centre, the house where the Guthrie family (they have a daughter of eleven) live is elegantly aged and comfortably spacious. The vast attic doubles as home studio, office and storeroom for his solo career, which is predominantly about albums but also occasional touring. Posters, photographs and record sleeves, detailing triumphs from Cocteau Twins and solo eras, line the walls.

These days, Guthrie sports a beard, the significance of which will become apparent. He once claimed to be ‘too fat to be a goth’, and given the cooking skills he displays over the weekend, he won’t be dieting any time soon. Cheerful and broody in equal measures, Guthrie keeps the conversation flowing, but the can of worms lies open, kicked around, its contents spilling out. The past still lives, heavy, bewildering and threatening, in his head, especially since he’s recently heard that Elizabeth Fraser, his Cocteau Twins partner, and his girlfriend for seventeen years (the couple have one daughter, born in 1989) was to play her first ever solo shows, a full fifteen years after Cocteau Twins had split. The problem wasn’t her belated return, but her plan to sing Cocteau Twins material, music that Guthrie had written and arranged, for which he says he will receive no credit during the expected adulation for the singer.

Fraser, on her part, has admitted that she finds Cocteau Twins too difficult to talk about; since 2000, she has only discussed it twice, and passes up the opportunity to recall her side of the story for this book, a story stained by dysfunction, vulnerability, substance addiction, childhood trauma and astonishing music. ‘You take each other’s breath away by doing something or saying something they never saw coming,’ she told Guardian in 2009 when she released her first solo single ‘Moses’ (a tribute to her late friend Jake Drake-Brockman). ‘They were my life. And when you’re in something that deep, you have to remove yourself completely.’

Guthrie’s memories are clearly torturous as well. Long after midnight on the first day of recollection, Guthrie disappears upstairs, returning five minutes later, beaming, with a box full of memorabilia, of cuttings, stickers, leaflets, tour laminates, letters. The next morning, Guthrie’s mood appears to make it more likely he’ll burn the box’s contents. ‘And then, I found that big bag of stuff,’ he wrote in an email a month after we’d met. ‘Goodness, some revelations were made which have left me feeling, if possible (!!), less comfortable with my past than even I could have imagined. My wtf? turned into a WTF? I feel like I’ve had surgery performed but the surgeon forgot to sew me back up.’

Earlier in the afternoon, he’d sat down to recall his and Fraser’s first visit to Hogarth Road. ‘I don’t remember meeting Ivo, but we already knew 4AD because we’d collected their records. We were enthralled by The Birthday Party and also Dif Juz. I quite liked Bauhaus, Elizabeth more than me, though I loved “Bela Lugosi’s Dead”, and Rema-Rema. We’d hear things on John Peel and read the music papers. I wasn’t into Cupol but I’d been a bit of a Wire fan. Burning Blue Soul was one of the best records of that decade, right out of the mould. But The Birthday Party was the most exciting thing I’d ever heard. And Rowland Howard’s approach to guitar – I didn’t realise you could do that and still be taken seriously.’

Equidistant from Glasgow and Edinburgh, on the banks of the Firth of Forth, ‘Grangemouth was a village around an oil rig,’ claims Ray Conroy, who was to become Cocteau Twins’ tour manager after first taking on Modern English through his brother Mick’s connection to 4AD. Guthrie and his schoolmate Will Heggie were among the town’s punk renegades, making stroppy, noisy protest in bands such as The Heat. ‘Punk to us didn’t mean your clothes, but doing what you want,’ says Guthrie. ‘Self-expression. A teenage cry for help.’

Guthrie had worked as an apprentice for BP Oil, with a talent for electronics, which he put to good use by building effects pedals for his guitar. ‘The aim was to make music with punk’s energy but more finesse and beauty, and that shiny, dense Phil Spector sound. I was trying to make my guitar sound like I could play it, so I was influenced by guitarists who made beautiful noise, like The Pop Group, or Rowland S. Howard.’

The new band couldn’t be complete until they’d found a singer. They vaguely knew a girl, Elizabeth Fraser, two years below them at school, who they’d see dancing at the Hotel International, a local club where Guthrie would sometimes DJ. His playlist included The Birthday Party and The Pop Group: ‘Most people weren’t happy with my choices, but Liz was, as she kept dancing,’ Guthrie smiles. ‘We struck up a bit of a friendship.’

Colin Wallace, one year above Guthrie and Heggie at school, recalls Fraser as, ‘This little vision in fishnet tights, leather mini-skirt and shaved head, smoking cigarettes, playing truant until lunchtime. Shy and quiet too. She was ostracised at school, as a weirdo, but to me she was unbelievably brave.’

Wallace recalls Guthrie saying, ‘If she’s that good a dancer, I bet she can sing. Robin asked her, and she said yes, but she wouldn’t even sing in front of Will. But I’d hear them rehearse, above some shops, and in the old derelict town hall, and she was astonishing.’

Guthrie: ‘Liz was insanely shy but as her mum later told me, she always sang as a child. We just assumed that she’d be brilliant, like I thought we were all great. We were very naïve and idealistic then.’

The name Cocteau Twins came via the Glasgow new wave band Simple Minds, who The Heat had once supported: ‘They had a song called “Cocteau Twins”, so we nicked it,’ says Guthrie. This wasn’t any reference to the fact that the band initially had a second vocalist: ‘Carol, a friend of Liz’s,’ Guthrie recalls. ‘But she only stayed two weeks. I forget why she didn’t last.’ There was also a drummer, John Murphy, though his request for travel expenses encouraged Guthrie to choose the cheaper and more manageable option of a drum machine. The band even broke up for a couple of months: ‘Liz and I probably fell out with Will, or he was busy elsewhere,’ Guthrie thinks. ‘But a friend asked us to support his band, so we re-formed.’

Fraser’s memory, in an interview with Volume magazine, was that she’d got fed up: ‘I didn’t feel like [the band] was for me at all … I think it was more the lyrics that I didn’t have the faith in. But I started going out with Robin, so I came back into the band.’

During rehearsals in the local community hall, Communist Party office and a squat the trio developed their nascent sound, and after just two shows, they recorded a demo of ‘Speak No Evil’, ‘Perhaps Some Other Aeon’, and ‘Objects D’Arts’ (Guthrie says Fraser purposely spelt it wrong). Fraser’s buried voice, Guthrie recalls, ‘wasn’t done on purpose, we just couldn’t record it any better. We only had one microphone and one cassette recorder, so we had to record the songs twice [Wallace says more than twice, as he has a copy too], once for a tape to give to Ivo, the other to John Peel when we met him [at The Birthday Party show]. We had no phone so I wrote down the number of the phone box down the road and “call between five and six” on the cassette box, and I’d wait outside every night for a call! There wasn’t a doubt in my mind that they’d both ring.’

Ivo initially sent the trio to Blackwing to record a single, where he was astonished to hear a voice rise out of the music’s shivery dynamic: a powerful, plaintive, hair-raising cry of a voice. Recording the new versions of ‘Speak No Evil’ and ‘Perhaps Some Other Aeon’ went so well that Ivo suggested Cocteau Twins record an album instead. The band readily agreed. ‘We got very handy at the night bus, up and down from Scotland, sixteen hours each way,’ says Guthrie. ‘No one would take us seriously in Scotland, or give us any shows, because we weren’t hipsters from Glasgow or Edinburgh, and we weren’t on Postcard Records.’

The Glasgow-based independent Postcard had been started in 1980 by nineteen-year-old Alan Horne as a vehicle for the band Orange Juice, fronted by his friend Edwyn Collins, whose knowing and inspired marriage of The Velvet Underground with The Byrds initiated the Sixties revival that was eventually to redefine the British underground sound, from The Smiths to The Stone Roses. Adding Josef K, a cooler and droll version of monochromatic post-punk, and the exquisite folk-pop of Aztec Camera, Postcard operated with a lightness of touch and irony – each record had the logo ‘The Sound Of Young Scotland’, a pastiche of Motown Records – with Horne more of a media-savvy, plotting figure in the mould of Factory’s Tony Wilson than reticent Ivo. As a result, Postcard had instantly been championed by the press in a manner withheld for the more heavyweight and less conceptual 4AD.

Ivo appreciated Josef K’s ‘It’s Kinda Funny’ but saw 4AD ‘as an alternative to Postcard’, though he says he understood Postcard’s dedicated following. Ivo would not have deviated from obeying his A&R instincts for a similar concept or status, yet it’s a curious coincidence that 4AD’s next find – via a demo – involved members of Josef K and a spindly, hyper-literate Postcard-ian pop that broke the conventional 4AD mould.

The Happy Family wasn’t the most satisfying or productive vehicle for the band’s singer-songwriter Nick Currie – or Momus, the alter ego he subsequently chose for his solo guise, after the Greek god of satire and mockery. Having lived in London, Paris, Tokyo, New York and Berlin over the years, Currie’s current home is Osaka, Japan, where he continues to fashion spindly, hyper-literate albums but in a electronic/folk fusion he calls ‘analogue baroque’. He also writes novels and essays, teaches the art of lyric writing and gives, he says, ‘unhelpful’ museum tours.

Currie was born in Paisley, to the west of Glasgow, a centre of printed wool manufacture that gave its name to the Indian pattern so popular among Sixties flower children. Currie was no hippie or drop-out, taking an English Literature degree at Aberdeen University while leaving time to study John Peel’s radio show at night. At a gig in Glasgow, he’d given Josef K guitarist Malcolm Ross a demo with instructions to pass it on to Alan Horne at Postcard, but Ross kept it, and after Josef K’s surprise split, Currie found himself in a band with Ross, Josef K bassist Dave Weddell and local drummer Ian Stoddart.

Currie christened the quartet The Happy Family. ‘It was tongue in cheek,’ he declares. ‘I already had a concept for an album, about two children in the [German terrorist organisation] Red Brigade who assassinated their lottery-winning fascist of a father.’ The anticipated album would be called The Man On Your Street: ‘It was about totalitarianism, the idea that your street equals the whole world, with fascism as a global threat, and mapping that with the oedipal dynamics of the family. My mother had just run off with a wealthy accountant with very conservative views. I was working through the break-up of my actual happy family.’

Currie hoped that his perception of Josef K’s ‘star power in the press’ would rub off on The Happy Family – ‘People were shocked by Josef K’s early demise and interested in what would come out of it,’ he says. Ivo admits he was one of them: ‘I never had any intense involvement with any of the band, but Nick was a smart fellow, and I liked his concept.’

Currie agrees that he and Ivo never bonded. Both men were shy, though Currie’s droll, intellectual way of compensation was more Alan Horne than Ivo. At their first meeting, Currie suggests, ‘To Ivo, I probably looked extremely young, skinny and chinny, and not like a pop star.’ Such criteria weren’t deal-breakers at 4AD, so Currie is probably more accurate when he adds, ‘I was probably an opinionated and prickly kind of fellow’, which also described Ivo to a point. But Currie did feel some connection: ‘Ivo was kindly and avuncular, a very good teacher and indoctrinator, with a very strong aesthetic, and he knew all this music.’

Currie also got a glimpse early on of Ivo’s home when The Happy Family stayed at his flat: ‘It was awful, suburban hell on the outside but aesthetic and tidy inside, painted lilac and everything filed away beautifully, with fine art coffee table photography books like Leni Riefenstahl in Africa and Diane Arbus. He drove us around in his BMW – the cheapest model [only leased, Ivo says], but still a BMW. So he resembled a playboy entrepreneur to me. But in his mild English way, he talked about his childhood on the farm. I said, “That’s great, all the family together like that”, and he looked at me strangely, like it was my ideal and not his.’ Which was true: a happy family wasn’t how Ivo remembered his past.

Before any album was recorded, Ivo wanted to release a Happy Family single. A three-track seven-inch headed by ‘Puritans’ was recorded at Palladium Studios, ‘a weird pixie-like place in the hills outside Edinburgh, a bungalow with a studio inside,’ Currie recalls. Ivo didn’t know it but Palladium would soon become as crucial to 4AD’s fortunes as Blackwing, handy for any local Scots and for bands that needed a residential wing for extended visits. Palladium was cheaper than Jacob’s Studios, and run by Jon Turner, a musician whose accomplishments were far in advance of any 4AD artist – he’d even regularly backed Greece’s psychedelic hero turned MOR entertainer Demis Roussos.

Blackwing was still the preferred choice for 4AD’s London-based acts, though Colin Newman preferred Scorpio Sound in central London, where he hoped to begin another solo album, this time of songs. But Beggars Banquet was less keen: ‘I’d got a good advance for A–Z and it hadn’t sold as many as they’d wanted,’ Newman recalls. ‘Beggars also wanted me to tour, which I didn’t. Because I wasn’t playing ball, they wouldn’t give me another advance.’ But Ivo was eager for a record of Newman’s off-kilter, Wire-style pop, and after agreeing a more modest budget, the album was finished, and even featured three-quarters of Wire, with Robert Gotobed and Bruce Gilbert among the guests.

If A–Z was the missing fourth Wire album, Not To was the fifth, and represented yet another diversion from the cornerstone sound of 4AD’s sepulchral origins. But the label’s reigning masters of foreboding were hardly down and out. A concert by The Birthday Party at London’s The Venue in Victoria had been recorded in November 1981, and though it would have been a bigger money-spinner as a whole album, the band didn’t think the recording was good enough to be released in its entirety, only picking four tracks (including a cover of The Stooges’ ‘Loose’) for a budget-priced EP. In reality, it was a mini-album since the band had had the idea to feature the evening’s support slot, Lydia Lunch.

From Rochester in the northern part of New York State, by her own admission, Lydia Anne Koch was a precocious child. She told 3:AM magazine that, when she was just twelve years old, she’d informed her parents that she needed to attend ‘rock concerts until well after midnight, for “my career”’. By fourteen, she was taking the train to Manhattan with ‘a small red suitcase, a winter coat, and a big fucking attitude’. At nineteen, she was fronting Teenage Jesus and The Jerks, a prominent part of America’s own post-punk response, known as No Wave, an experimental enclave marked by dissonance, noise and jazzy disruption. Lunch’s confrontational howls chimed with The Birthday Party’s own, and after she’d attended the band’s third New York show in October 1981, a budding friendship led to Lunch being added to the Venue bill with an impromptu backing band that included Banshees bassist Steven Severin.

The vinyl’s Birthday Party side was called Drunk On The Pope’s Blood; the title of Lunch’s side, the 16-minute The Agony Is The Ecstasy, nailed the essence of the semi-improvised atonal festival of dirge. A month after its release in February 1982, The Birthday Party once again returned to Britain after another profitable summer’s break in Australia, both touring and recording a new album. Only this time, bassist Tracy Pew had had to remain behind, detained in a labour camp for three months following a drink-driving offence. His deputy was Barry Adamson, bassist for Manchester new wave progressives Magazine, who had befriended The Birthday Party after marrying one of their Australian friends. Bottom of the bill at The Venue was a band playing only their third show – Cocteau Twins. ‘Talk about being propelled into it,’ says Guthrie.

The Cocteaus had returned to Blackwing to record an album, which Ivo had scheduled for September, leaving time and space for a series of less pivotal 4AD releases. Daniel Ash was the next escapee, after David J, from Bauhaus, collaborating with school friend (and Bauhaus roadie) Glenn Campling for a four-track EP, Tones On Tail, whose unusual rhythm and ambience was more Cupol than Bauhaus. ‘I was pleased that Daniel contacted me about something outside Bauhaus, and I liked him, and said yes,’ Ivo recalls. ‘No offence to Daniel, but for me, it’s one of the least essential of 4AD releases.’

Ivo considered In Camera’s latest release to be one of the more essential of 1981, certainly among the band’s own records. But the band’s three-track Peel session, which had been recorded at the end of 1980, was named Fin because it was their epitaph. The 11-minute ‘Fatal Day’ suggested a band at the peak of its powers, but like Dance Chapter, In Camera had fallen apart after one seven-inch single and EP, finding that ethics had become an insurmountable barrier.

A fear of compromise had eaten away at the band’s soul. Contracts were the first issue. ‘We signed one [for the EP], which wasn’t a very good deal,’ says Andrew Gray. ‘But what terrified us was that if we sold x amount of units, Beggars could nab us, as they’d done with Bauhaus, and we’d have had to strike up new friendships.’

Ivo says they shouldn’t have been worried. ‘In Camera wasn’t a group to make the same transition as Bauhaus. We were only doing one-off contracts by that point. Beggars had decided very quickly to let young, or independent, people get on and work.’

Other personal pressures were present as well. There was an intensity to In Camera’s mission: David Scinto recalls one drunken moment when he and bassist Pete Moore did a blood-brothers ritual, ‘Pete with a knife, me with a Coke can ring. That was nasty. But that’s the sort of thing you did.’ So no decision was ever taken lightly. When Ivo had requested an album, and Moore and drummer Jeff Wilmott felt ready, Scinto decided they needed more songs while Gray was again ‘terrified’ a producer might corrupt the band’s fiercely protected sanctum of unity. ‘Any ideological flaws,’ says Gray, ‘meant we couldn’t carry on.’

‘For the band,’ Scinto muses, ‘we’d tried to remove our egos. But ego drives you on. I guess we didn’t have the ego to fight for the band.’ Scinto certainly lacked the ego of a frontman, a rock star. ‘I would have given anything to be a rock star!’ Wilmott laughs. ‘But we’d all sat back and let things happen, rather than drive things ourselves. We almost expected 4AD to do the work. Most gigs were arranged by Peter [Kent], and we should have been gigging every other night. We were jealous of Bauhaus’ relationship with their tour manager, who pushed and assisted them in achieving their goals. But I still wouldn’t change a thing about how we interacted. In Camera was more like an art club than a band.’

The variety of personalities trying to make headway in post-punk times – art school experimentalists, musical terrorists, career opportunists, politically driven ideologists – ensured that most independent labels of any stature would represent a menagerie of interests. For every aesthetically rigid In Camera, there were more pliable types like Modern English, who happily accepted Ivo’s suggestion of a producer for their next album who, says Mick Conroy, ‘could make more sense out of us’. Hugh Jones had produced Echo & The Bunnymen’s panoramic 1981 album Heaven Up Here, which was widely admired by both Ivo and Modern English. Jones provided an instant reality check. Conroy recalls asking him what he thought of their songs: ‘Hugh replied, “There aren’t any”.’

But Jones says he was still attracted to the project. ‘I liked bits of Modern English’s music, but more, I just liked them, which is my chief criteria, along with having chemistry with an artist. I also thought I could contribute a lot.’

Jones had engineered Simple Minds and Teardrop Explodes albums before stepping up to produce the Bunnymen; all had been major-label commissions. Ivo was, he recalls, ‘the first record company person I’d met that didn’t come across as brash’. The pair also bonded over favourite albums: for example, both believed The Byrds’ Notorious Byrd Brothers was a contender for the best album ever made. In the process of working with Modern English, Jones says he introduced them to the delights of British folk rock luminaries Nick Drake and Fairport Convention, and American pop-soul prodigy Todd Rundgren, to give them an insight into chorus-led songwriting and arranging.

Out of it came a distinctly altered Modern English. When Ivo had reckoned that pop bands were unlikely to approach 4AD, he wasn’t expecting it would come from inside the 4AD camp. The band named the album After The Snow: ‘Mesh & Lace had been a very cold, angry record,’ says Robbie Grey.

Just as Echo & The Bunnymen and Orange Juice had bypassed punk’s disavowal of music of a radically different hue by respectively resuscitating The Doors and The Byrds, After The Snow had adopted a broader, defrosted outlook. There was even a flute on ‘Carry Me Down’. ‘Ivo thought Gary’s guitars sometimes resembled The Byrds, whereas he’d previously sounded like he was kicking a door in!’ says Conroy. ‘I think making the album in the Welsh springtime meant that we ended up sounding like the countryside.’

By comparison, The Birthday Party resembled a night in a city gutter. The band had returned from Australia with a virtually complete new album, Junkyard, on which Barry Adamson had played most of the bass given Tracy Pew’s incapacitated status. The artwork by the cult cartoonist and hot rod designer Ed ‘Big Daddy’ Roth featured his Junk Yard Kid and Rat Fink characters on a journey towards, or from, mayhem, and the album was rife with exaggerated figures such as ‘Dead Joe’, ‘Kewpie Doll’ and ‘Hamlet (Pow Wow Wow)’, and pulp-fiction violence – for example ‘6" Gold Blade’ and ‘She’s Hit’. The band drove the point home with exhilaratingly malevolent moods, with Nick Cave acting the snorting and dribbling despot. If only the Mass album Labour Of Love had managed to articulate their own drama and tension in the same manner.

By having both Modern English and The Birthday Party at the label, 4AD showed it could handle dark and light: from Ed Roth’s craziness to Vaughan Oliver’s graceful design for After The Snow, with dancing horses on a backdrop of crumpled tissue paper inspired by a line on ‘Dawn Chorus’ (‘strange visions of balloons on white stallions’). ‘That was a breakthrough, graphically, my first extensive use of texture to create a mood,’ Oliver says. ‘It was an act of perversity but also of tenderness, given it was tissue paper.’

While The Birthday Party was giving the impression of heading further out of control, Hugh Jones had guided Modern English to a newly minted pop levity. 4AD adapted accordingly, acting like a major label by taking a single from an album before the album was released. ‘Life In The Gladhouse’ was sleek and gutsy with a busy funk chassis, a musical advance but also a commercial retreat, losing the band the post-punk audience cultivated via John Peel without replacing it with a mainstream audience. It reached 26 in the UK independent chart, ten places lower than even ‘Smiles And Laughter’.

The Birthday Party had made no such alterations, plunging further onward, on tour through the UK and Europe with Tracy Pew back in the ranks. It wasn’t a surprise that the wheels were falling off this careering bus, the first instance being the sacking of odd-man-out drummer Phil Calvert, with Mick Harvey taking his place both on stage and in the studio. What’s more, the bus was leaving town for good. The Birthday Party decided they were over Britain, and having met Berlin’s industrial noise fetishists Einstürzende Neubauten, the Australians chose the divided city as its new base.

Ivo had funded new recordings at Berlin’s famous Hansa Studios (where David Bowie had recorded his ‘Heroes’ classic), but before the band departed, Lydia Lunch and Rowland S. Howard (who had formed an alliance and played several of The Birthday Party shows as the support act) offered Ivo a cover of Lee Hazlewood and Nancy Sinatra’s 1960s psychedelic oddity ‘Some Velvet Morning’ that they’d recorded in London. 4AD duly released it as a twelve-inch single, with the original ‘I Fell In Love With A Ghost’ on the B-side, and much the better track; Ivo’s fondness for the A-side is perplexing given his love of singing, and given the Lunch/Howard duet features a man who couldn’t sing and a woman who gleefully sang out of tune, desecrating the song’s magnetic allure.

‘Some Velvet Morning’ showed that although Ivo’s own taste might lean towards the extended listening experience of the album format, he remained committed to singles, a collectable and affordable format that could sell in tens of thousands. Following the pattern of Gilbert and Lewis, Colin Newman followed up an album with a new seven-inch, ‘We Means We Starts’. However, he didn’t intend it to be his last 4AD release.

Ivo recalls Wire’s re-formation as the reason it was: ‘I don’t remember turning down more of Colin’s demos,’ he says, though the band’s reunion was still two years off. Newman says he did submit demos to 4AD, which, he says, ‘Ivo didn’t think were pop enough’. But the singer’s dissatisfaction went deeper. ‘I didn’t have a way forward at that point. Independent labels tended to live on a wing and a prayer, and if things work out or not, it’s fine either way. I didn’t feel part of how everything worked at that time, and so I disengaged myself. I’d been to India for fourteen months and I’d had enough of the beast of the music industry. I did vaguely talk to Ivo about another project, but we drifted apart. I don’t feel close to those records I did on 4AD, or that part of my life.’

Newman also admits to other frustrations with Ivo: ‘He didn’t want me to produce his bands, even though I’d produced an album for [Irish art rockers] The Virgin Prunes that had done really well. And I think I’d have been more honest with his bands than he would have. I think he had his eye on producing himself.’

Ivo does recall a conversation with Newman about production, but says the only outside producer in 4AD’s first three years was Hugh Jones. ‘Most bands wanted to produce themselves and we didn’t have the budgets that Colin was used to with EMI and [Wire producer] Mike Thorne. It’s lovely to fantasise about what, say, the Mass record would’ve sounded like had they been interested in input and Colin had been keen to get involved.’

As Newman suggests, Ivo did take a more active role in Cocteau Twins’ debut album. Garlands was recorded at Blackwing, with Eric Radcliffe and John Fryer engineering and Ivo given a co-producer credit alongside the band. Guthrie recalls they had quickly regarded Ivo as a mentor: ‘He was very intelligent, one of the first grown-ups we’d met, with a car and a flat; we didn’t know anyone like that! He was switched on to music, and he was listening to us! We were enthralled by him.’

Ivo, however, downplays his role. ‘I might have suggested an extra guitar part, or sampling a choir at the end of “Grail Overfloweth” in the spirit of [krautrock band] Popol Vuh’s music or sampling Werner Herzog’s masterpiece, Aguirre, the Wrath of God, but it was minimal stuff. I also suggested, stupidly, extending the start of “Blood Bitch”. But I was there because someone had to say yes or no, and the band lacked the confidence to do so.’

Elizabeth Fraser was an especially vivid example of deep-set insecurity. Back in Rennes, Guthrie paints a picture of a girl who left home at fourteen, with Sid Vicious and Siouxsie tattoos on her arms, self-conscious to an almost pathological degree. In the mid-1990s, after becoming a mother and having therapy, Fraser told me about the sexual abuse she suffered in her youth, from within her own family. In 1982, she was still a teenager, her issues still fresh and unresolved, and facing not just decisions about her life but being judged on her creativity.

‘When we mixed the album, you’d isolate an instrument or voice to concentrate on it,’ says Ivo. ‘Whenever we’d solo Liz’s vocal, she wouldn’t let it be heard, or she’d have to leave the room. She had very low self-esteem. On stage, she’d wear a very short mini-skirt and bend over, showing her knickers, and she’d strike her bosom. She was a striking presence on stage, doing all this stuff with her fingers, and you’d see the pain on her face.’

Guthrie later told the NME that Garlands sounded ‘rather dull compared to what we know we’re capable of’, but it was a promising start. ‘In the same way as 4AD hadn’t yet proved its individuality, the Cocteau Twins didn’t with their first album,’ says Ivo, but both label and band could be proud of creating an uncanny and original template with such extraordinary potential. Garlands may have drawn some comparisons to Siouxsie and the Banshees, but it had its own enchanted and anxious tension. Heggie’s trawling bass and Guthrie’s effects-laden yet still minimalist guitar was rooted to a drum machine that occasionally lent a quasi-dance pulse. It gave Fraser a restlessly inventive backdrop for her melodic incantations and lyrical disorder, for example: ‘My mouthing at you, my tongue the stake/ I should welt should I hold you/ I should gash should I kiss you’ (‘Blind Dumb Deaf’) and, ‘Chaplets see me drugged/ I could die in the rosary’ (‘Garlands’).

The sleeve dedication to Fraser’s brief singing cohort followed suit: ‘Dear Carol, we shall both die in your rosary: Elizabeth.’ There were thanks to Ivo, Yazoo’s Vince Clarke, who lent the band his drum machine, and Nigel Grierson, whose photo graced the cover. Robin Guthrie disliked the Banshees comparisons, so it’s good he didn’t know the original inspiration behind the photo, which Grierson says the band selected from his portfolio; it had been part of a college project on alternative images for Siouxsie and the Banshees’ own album debut The Scream. ‘I didn’t hate it, but I didn’t want it, and I wasn’t asked,’ Guthrie counters. ‘It looked really gothy, and we had enough trouble with that as it was, with our spiky hair! We quickly got a goth audience but we never wore black nail varnish.’

Ivo disputes Guthrie’s statement that the band weren’t consulted; Grierson suggests that the trio’s chronic shyness meant they never articulated their own views or verbally disagreed. The mercurial Guthrie takes another view: ‘[The band appreciated] everyone was helping us make this record, but the underlying attitude was, what do you know about art? You never went to art school. You’re not an aesthete, you’re from Scotland.’

But Ray Conroy confirms Grierson’s summary. ‘Cocteau Twins would stay at my flat. I was their translator; they were so shy and timid,’ Conroy explains, adding: ‘Liz had her head shaved all round the side, with a long ball on top of her head, like a pancake or a bun had landed on there. With Robin and Will, it was all about hairspray! Boots unperfumed. And the amount of speed they did! A ton of it. It was all part of the fun.’

Yet amphetamines didn’t loosen anyone’s tongues. Chris Carr was entrusted with the duo’s first press coverage. ‘Liz and Robin were so incredibly shy, I thought that if anyone was to interview them, could the journalist hear them speak? How could we overcome this? But Ivo had faith. And he knew that, musically, something was there.’

As it turned out, Guthrie did speak up in interviews, and was hardly shy; more headstrong and even comical. ‘How can we be stars when we’re so fat?!’ he asked NME journalist Don Watson. Guthrie also expressed shock at Garlands’ extended occupancy in the independent charts despite ‘hardly any reaction from the press,’ he claimed. John Peel’s role could never be underestimated.

The interview made up in part for the fact that NME hadn’t reviewed Garlands, though Sounds praised, ‘the fluid frieze of wispy images made all the more haunting by Elizabeth’s distilled vocal maturity, fluctuating from a brittle fragility to a voluble dexterity with full range and power’. Even so, Guthrie felt the trio were much better represented by the sound – and art – of the Lullabies EP that followed just a month after the album. For this, Grierson chose two complementary images of a dancer and a lily, illustrating an elegant beauty over any overt angst and darkness. ‘At least they asked us about that one,’ Guthrie concedes.

Lullabies’ three tracks – ‘Feathers-Oar-Blades’, ‘Alas Dies Laughing’ and ‘It’s All But An Ark Lark’ – were written specifically for the EP, and initially recorded at Palladium where Jon Turner’s newly purchased and expensive Linn drum machine added a crispness and a drive to the Cocteaus’ base sound. Overdubs were added in London, the petrol for the trip from Grangemouth paid for by shows in Bradford and Leeds along the way.

A measure of how quickly Cocteau Twins’ popularity grew is that all three Lullabies tracks made John Peel’s annual Festive Fifty listeners’ poll. Added to The Birthday Party’s unnerving charisma, Cocteau Twins’ mercurial charm upped 4AD’s profile and credibility. According to John Fryer, ‘NME would review 4AD like, “another shit record on 4AD”, but after the Cocteaus, it was, “this amazing label that signed this amazing band; the future of music”.’

‘You knew something was happening,’ Chris Carr agrees. ‘And Ivo had great faith in Cocteau Twins. They weren’t out there like Mass, but left of centre enough for things to develop. There was a new wave of music journalists arriving, and discovering their own music, and from here on in, 4AD started being taken more seriously. You could identify Ivo’s vision, his mission statement. He knew what he wanted to sign, and it wasn’t going to be the next whatever, but things that had their own individual fingerprint. And everything had to be as right as possible, down to the artwork. His vision was different. It wasn’t sexy but people were getting seduced.’

This growing profile included a newly expanding audience in the States, where this strange, enigmatic parade of records housed in often oblique artwork, culminating in Garlands and Lullabies, had struck a chord.

‘My friend Leo said, “If you like David Sylvian and Japan, you need to hear Cocteau Twins”,’ recalls Craig Roseberry, a New York-based producer, DJ and record label owner who was a deeply impressionable teenager at the time. ‘Garlands was fantastic, and I asked another friend who worked in a record store if he had more records on 4AD. He mentioned Modern English and Bauhaus. I bought “Dark Entries”, and after that I needed everything on 4AD. I’d heard all this British music at [New York club] Danceteria, yet nothing on 4AD sounded like anything else.’

Fronted by David Sylvian, Japan’s sound was austere and romantic, a world unto itself. Roseberry found 4AD similarly fascinating: ‘It defied definition, but evoked the same feeling, what I’d call an “other otherness”. It was an esoteric version of music like Siousxie and the Banshees, music to the left of what was already left of centre. By then, I’d discovered lots of art, like Bauhaus and Dada. I understood from 4AD artwork, which was just as left field, that 4AD was coming from an art aesthetic more than simply music. It was informing me how to see the world.’

Roseberry began collecting every 4AD release, right back to Axis. ‘It was something to obsess over, even more than with Prince or David Sylvian. It was more obscure and niche and when you found it, you cherished it because it seemed to appear out of nowhere. It had such mystique. But what struck me the most was the catalogue numbering! So I had to own it all, and file everything in sequence. 4AD was more than a record label or art house; it became a culture.’

The attention to cataloguing aided the collectability of 4AD (the prefixes extended to DAD, GAD and HAD). It was all part of the bespoke detail that set independent labels apart from the majors. It created an identifiable culture that had grown big enough to support its own distribution system and trade magazine. The Cartel was a new association of independent regional UK distributors, which was partly funding the monthly title The Catalogue, which was based in the Rough Trade distribution offices, with listings and features covering the ever-expanding alternative movement of labels and artists.

The Catalogue’s Australian-born founding editor Brenda Kelly had first discovered 4AD while working at Melbourne’s alternative radio station 3RRR. ‘The Birthday Party was a key and radical Melbourne band, and any label that signed them had to be interesting, but what first attracted me to 4AD was Cocteau Twins,’ she says. ‘All of the four big UK independents – 4AD, Rough Trade, Factory and Mute – had maverick qualities, but, more so even than Factory, 4AD was special because it created an atmosphere around beauty. It was art for art’s sake. The artwork gave 4AD the most clearly articulated and uncompromising identity, which was crucial to the independent movement at that time – things were more complex and subtle than “do it yourself”.

‘People forget that art is a part of youth culture rather than just a succession of trends or an attitude, and such a consciously arty label like 4AD meant the independent scene was enriched and broadened. It created a space for bands and labels to build a roster and create a strong identity and base for their bands. Some independent labels, particularly 4AD, didn’t talk much about the politics of independence, but Ivo understood and supported the space that independent distribution created.’

If enough people responded with the same belief and support as Kelly and Roseberry, 4AD had a fighting chance of creating something bigger than an esoteric cult. If there could be songs that US or UK mainstream radio responded to, there might even be hits, to match Depeche Mode at Mute or New Order at Factory. Modern English were 4AD’s best hope, and in the major label tradition, a second single was plucked off After The Snow after the album had been released.

‘I Melt With You’ had a simple structure, breezy timbre and matching chorus, which Sounds writer Johnny Waller described as, ‘a dreamy, creamy celebration of love and lust’. Yet the single barely broke the indie top 20. The video showed 4AD’s inexperience in catering to a broader demographic: ‘It was one of the most awful we ever did,’ Ivo recalls. ‘It was filmed in a dingy basement with two hired dancers, and Robbie bleeding from a scab after a cat had scratched his face.’

If Modern English’s new identity had lost John Peel’s patronage, The Happy Family never had the DJ on side to begin with. This was despite the fact that Peel had always supported Josef K, and line-up changes increased the number of former Josef K personnel; though Malcolm Ross and Ian Stoddart had left (the former, to join Orange Juice), their respective replacements were Josef K roadie Paul Mason and drummer Ronnie Torrence. New keyboardist Neil Martin made five).

Nick Currie recalls that The Happy Family had effectively ambushed Peel at the BBC Radio 1 offices, to hand over the debut album, The Man On Your Street. ‘I saw [Altered Images singer] Claire Grogan in the lobby, who Peel was famously besotted by, and when John emerged, my first words where, “Oh, we just saw Miss G”, with a saucy grin on my face. He looked really embarrassed, as if he’d been consorting with her. It was embarrassingly awkward. Peel never did give us a session.’ Despite his very public profile, Peel was as shy as Ivo (whose approach in the past had been to send the Cocteaus-besotted DJ his own acetate of Garlands, letting music alone do the talking).

The album didn’t find much press favour either. The album’s brittle, wordy atmosphere was always going to be divisive: Don Watson at NME – reviewing it two months after release – seemed divided himself, referring to the album’s ‘flat sound that borders on dullness’, but also saying, ‘It barbs your brain with a bristle of tiny hooks.’ Currie says Josef K supporter Dave McCullough at Sounds was more certain: ‘He gave it a bit of a trashing, saying it was too verbose, and the time wasn’t right for the return of the concept album.’

Indeed, The Man On Your Street was the least popular album in 4AD’s early years, selling just 2,500 copies. Currie thinks Ivo wasn’t that keen on the record himself: ‘The song he liked the most of ours was “Innermost Thoughts”, which to me was the musical equivalent of 23 Envelope sleeves, a delicate object, with a fully-flanged bass line that was the hallmark of miserablist bands at the time. But the album had moved away from that style. I’d got sick of all the long raincoats, the Penguin Modern Classics book poking out of the pocket top, the Joy Division scene. [NME’s] Paul Morley was the critic of the time, and he was promoting this new, shiny, happy pop music [meaning the likes of ABC, and also Orange Juice] after turning his back on miserablist Scottish pop. The Happy Family was going with that tide, moving away from 4AD’s aesthetic.’

Currie had also declined Vaughan Oliver’s input, going for his own bizarre mish-mash, a Sixties retro layout that included the subtitle Songs From The Career Of Dictator Hall and an out-of-place primitive folk art drawing to the side of a colour photograph of the earth. ‘I stubbornly wanted to do the cover myself,’ he admits. ‘The photo of the globe cost Ivo a lot more than Vaughan!’ It was more expensive, actually, than the album’s recording budget, which illustrated 4AD’s commitment to packaging.

Currie thinks The Man On Your Street would have fared better if Oliver had taken over, giving it an identifiable 4AD cachet: ‘We were an anomaly on 4AD. I was deliberately trying to undermine their image, to show 4AD could go to other places. I think Ivo was flummoxed by our brash, alienating irony and a narrative music hall sensibility that was at odds with him, and we didn’t have that sense of beauty that he liked. It also had this Puckish, communist streak, and I don’t think we saw eye to eye politically. But I’m very grateful to Ivo. It was a terrific adventure.’

Currie also saw Ivo’s patronage and 4AD’s early achievements as part of a watershed era for British music. ‘It was the first generation of record label bosses who were creative themselves, and trying to shape a sensibility. Though in the end, I found it easier dealing with old-fashioned record labels that were just a marketing department and a bank!’

As Momus, Currie thrived, but The Happy Family didn’t. ‘Ivo wasn’t interested in another album, nothing was happening in Scotland, and I felt guilty about being the band’s dictator, even though the others wouldn’t write their own parts. The more we rehearsed, the worse we sounded, so I returned to university before moving to London.’1

If Ivo’s intuition had failed him on this occasion, his next discovery was another maverick mould-breaker in the Happy Family tradition, albeit in a radically different form. Coming at the end of the year, it finally put paid to the idea that 4AD was a repository of Stygian gloom – even if the title of Colourbox’s debut single was ‘Breakdown’.

From his home in the Regency seaside town of Brighton on England’s south coast, Martyn Young seems to have as many reasons as Robin Guthrie to consider his past in a someone regretful light. The fact is he is the driving force behind the only act in UK chart history never to have attempted a follow-up to a national number 1 single. In fact, Young and his younger brother Steven haven’t released one piece of original music since Colourbox’s spin-off project M/A/R/R/S scaled the charts with ‘Pump Up The Volume’.

Not that Young cares: he admits that he never truly wanted to make music to begin with, preferring the technical aspects of music, the manuals and the mixing desk; a boffin at heart rather than a musician, who has spent his ensuing years computer programming and studying music theory. In any case, he now has twins (two years old at the time of writing), and though his first course of anti-depressants (he and Ivo have exchanged emails about brands and effects) have lifted him, he doesn’t imagine he will make any more music. Given its association with depression, anger issues, creative blocks, writs and extreme food diets, why would anyone choose to return?

Young was born Martyn Biggs, which, he says, ‘sounded like “farting pigs”, so I used my mother’s maiden name of Young’. Home life was dysfunctional; his father had been sent to prison before Martyn was a teenager. At school in Colchester in the East Anglia region, he was two years above his brother Steven and Ray Conroy (whose brother, Modern English bassist Mick, was a year below them). Young’s musical path is familiar: a Bowie obsession led to a wider appreciation of art and progressive rock before punk’s conversion. ‘It immediately made me want to play guitar,’ he says.

Young says his first band, The Odour 7, was only a half-hearted teenage exercise, but the following Bowie/Devo-influenced Baby Patrol released a single, ‘Fun Fusion’ on Secret Records. ‘We were particularly crap and I destroyed every copy of the single I could find. I’m singing and the lyrics are so embarrassing. But I was still young.’

After dyeing his hair following Bowie’s blonde/orange rinse, Young was labelled a ‘pouf’ by his father and told he couldn’t sleep in the same room as his brother. ‘So I started squatting with Modern English in London.’ In this new world, Young borrowed a synthesiser and drum machine and spent a year unlocking their secrets. His next move was a band with Steven (known as Scab because of the scabs on his knuckles that he kept picking, Ivo explains) and Baby Patrol’s Ian Robbins; Colourbox was the title of an animated film from 1937. Mutual friends introduced female vocalist Debian Curry and the quartet recorded a demo that included ‘Breakdown’ and ‘Tarantula’. As Ivo recalls, Ray Conroy – acting as the band’s manager – came to Hogarth Road in 1980 to give the more dance-conscious Peter Kent the Colourbox demo, ‘because why would 4AD put out a dance record? I guess Peter wasn’t around, so Ray played me the tape. I liked “Breakdown” but I loved “Tarantula”. It’s such a sad song.’

Musically, ‘Tarantula’ resembled the moody cousin of Yazoo’s synth-pop ballad ‘Only You’, but unlike Yazoo singer Alf Moyet, Debian Curry’s cool delivery reinforced the withdrawn mood at the song’s core: ‘I’m living but I’m feeling numb, you can see it in my stare/ I wear a mask so falsely now, and I don’t know who I am/ This voice that wells inside of me, eroding me away …’

‘I’ve only recently come to understand that I’ve always suffered from depression,’ Young says. ‘I used to think my strange mood swings were caused by something like food, so I’d try and eat raw salad for months. But anti-depressants mean I’m no longer wallowing in misery and pent-up negativity.’

Ivo and Martyn Young’s bond wasn’t just musical, but personal, united by their shyness and sadness. ‘Ivo had a reputation for being dour, but he wasn’t with us,’ Young recalls.

Ivo: ‘I really liked Martyn. He looked like he was chewing gum and smiling at you at the same time, which was charming. Scab was younger and quieter, and the best drum programmer I’d ever met.’

Steve Young was also a good pianist and arranger, with Ian Robbins making a trio of strong contributors to the Colourbox sound. They were also interested in the new electro-funk sound that had succeeded disco as the prevailing club soundtrack in America’s clubs and street scenes, led by Mantronix and Afrika Bambaataa, which filtered into ‘Breakdown’, making the A-side of Colourbox’s debut single a brighter and more pulsing affair than its flipside ‘Tarantula’.

The single stood at odds with 4AD’s last release of the year, a compilation title released by Warners’ Greek office that was named Dark Paths, which undermined the fact that Ivo had begun to shed the gothic image. Only seven acts were selected: Bauhaus, Rema-Rema, Modern English, Mass, Colin Newman, Dance Chapter and the David J/René Halkett collaboration. In fact, over three years, 4AD had released more than fifty records by thirty acts; a pattern that Ivo recognised was unsustainable in the long run.

‘It took a few years for me to find my focus, and my confidence, and to get a feel for what the label might become,’ he recalls. ‘And to be absolutely happy to not have many releases. The less, the better, I thought! I was constantly counting our artists, and if we had more than six, I’d get nervous. But that hadn’t been possible in the first few years. We had no long-term contracts, no real careers. Besides Modern English, everyone was contracted record by record.’

The haphazard nature of 4AD’s development – the one-offs, the artful projects, the short shelf life of bands that promised much more, and both Bauhaus’ defection and Modern English’s slow progress – confirmed that Ivo really had no game plan to speak of. Things could either lead nowhere in particular or could build to something tangibly greater than the sum of its parts. In any case, Ivo had imagined 4AD would only be an interlude in his life, though it wasn’t true, as an offhand comment of Ivo’s had claimed, that the four in 4AD stood for the number of years he anticipated it would last.

But while it did last, Ivo could only follow an intuitive, personal path, one that paid no notice to the social and political traits of the staff at the NME who thought large swathes of post-punk had reneged on punk’s revolution. Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren – who had continued to ruffle feathers with his new puppets of outrage, Bow Wow Wow – mocked what he saw as a return to, in the words of writer Simon Reynolds, ‘student reverence and cerebral sexlessness’.

But, in light of music’s powerful effect beyond polemic, there was another way to view 4AD’s anti-manifesto. In January 2013, for a profile of Bosnian singer Amira Medunjanin in The Observer newspaper, journalist Ed Vulliamy also interviewed a law professor, Zdravko Grebo, who had begun an underground radio station, Radio Zid, during the Serbian siege of Bosnia’s capital Sarajevo during the Nineties. ‘The point was to get on air but resist broadcasting militaristic songs,’ explained Grebo. ‘Our message was: remember who you are – urban people, workers, cultured people. We thought the situation called for Pink Floyd, Hendrix and good country music, rather than militaristic marches.’

Nick Currie, one of 4AD’s most articulate observers, could also see what 4AD had achieved, and what might come:

I saw 4AD as a coffee table label, with a mild bourgeois aesthetic worldview, which appealed to other tender-minded people. Ivo seemed attracted to suburban places to live in or an office slightly out of the centre of town, with these semi-detached English houses, but then you’d notice some of those very houses had an Arts and Crafts sensibility, with stained glass windows, which opened my eyes to the possibilities of being an aesthete, and importing those sensibilities into people’s lives. Indie labels were not so well known or established at that time, yet labels like 4AD and Factory were already so refined, in a new hyper-glossy manner, with top-flight art direction. It was at the peak of post-modernism, and it felt distinct from what had come before. In my mind, Ivo and Vaughan were very much going to define the decade.

1 In 1983, Currie signed to London independent Cherry Red’s artful imprint él and released his first recording, The Beast With Three Backs EP (catalogue number EL5T), under the name Momus. Currie’s new baroque folk sound felt more like 4AD than The Man On Your Street. Currie sent Ivo an advance copy of the EP. Inside was a sheet of paper with a limerick that gently mocked 4AD, as well as the label’s system of catalogue numbering that has assisted in its collectability: ‘There was a songwriter so glad to be given two sides of a CAD/ That his blatant good humour carried dangerous rumours/ That life was more funny than BAD/ But when he composed EL5T consistent in perversity/ He slowed and depressed it, dear Ivo you’ve guessed it–/ He out 4AD’d 4AD!’ Sadly, it never reached Ivo, or he never realised the sheet was inside before selling it. The EP, with sheet of paper still inside, was eventually bought in a second-hand store and its purchaser revealed the limerick in an online blog.