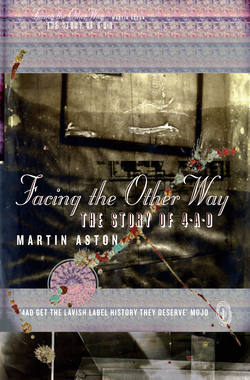

Читать книгу Facing the Other Way: The Story of 4AD - Martin Aston - Страница 15

chapter 6 – 1983 The Family That Plays Together

Оглавление(BAD301–MAD315)

The conversion of a large dry cleaning and laundry service gave the Beggars Banquet and 4AD labels the chance to leave the Hogarth Road shop for a standalone office. Alma Road was a street of Victorian houses in London’s south-western borough of Wandsworth, an anonymous suburb six miles from central London’s entertainment hub where every major record label occupied office blocks or stately mansions. The Slug and Lettuce pub was conveniently located on the opposite corner of the road from their building, at number 17–19.

Alma Road also symbolised the difference between 4AD and its independent label peers. Mute was based over in the west London enclave of Westbourne Grove, near to Rough Trade’s shop and label, deep in the heart of Notting Hill, the heartland of West Indian immigration, reggae, Rock Against Racism, carnivals, riots and streets of squats, a thriving low-rent bohemia that had made the bumpy transition from the hippies to the punks. Wandsworth had its less salubrious quarters but carnivals and riots were in short supply.

With room to breathe, and enough funds, Ivo also took on his first employee: Vaughan Oliver, who had previously been designing in a freelance capacity. Ivo knew design and packaging was part of 4AD’s identity, a visual language that gave 4AD an extra dimension of distinction. He could also see that many of 4AD’s artists were producing sub-standard images when left to their own devices.

It was a mutual admiration society between the two figures; strongly opinionated, stubborn and deeply involved with their particular line of work. ‘Ivo had this whole world of musical knowledge that enthralled me, and I looked up to him, and adored him, from the start,’ Oliver recalls. ‘And I think he had a secret admiration for me, educating him visually.’

Ivo: ‘Vaughan singlehandedly opened my eyes to the world of design. In his portfolio, he had samples of Thorn EMI light bulb sleeves. It hadn’t occurred to me that behind every object, utensil or drainpipe was a designer and I never saw the world in the same way again. Maybe I didn’t show it at the time, caught up in the sheer business and joy of watching this thing called 4AD blossom, but it was a privilege that I still cherish, sitting four feet away from this outpouring of creativity. Nigel [Grierson] was around a lot too and Vaughan and Nigel at full throttle was an experience to remember.’

The friendship was firmly based around work: ‘We didn’t talk about anything but music, and we didn’t have a drink together – Ivo didn’t go to pubs,’ Oliver says. ‘Whereas one reason I took the job was the pub over the road!’

As Ivo discovered, Oliver was not one to dirty his hands with anything but ink. ‘I seriously expected Vaughan, like any other employee when they later joined, to help unpack the van when it arrived with records. But you’d always have to track him down. I saw very early on, for example, that he’d take two weeks to design, by hand, each individual letter for the Xmal Deutschland logo. Design was a full-time job for Vaughan.’

Oliver’s first task as staff employee was The Birthday Party’s new four-track EP, The Bad Seed. The band had handled its own artwork to date, with mixed results, and Oliver was forced to work with supplied ideas: the band’s four faces and realistic illustrations of their core subjects, a heart wrapped in barbed wire, a cross and flames. The contents were much more inspiring, ‘Deep In The Woods’ tapping a newly smouldering vigour (perhaps because, for the first time, Rowland S. Howard didn’t write anything on a Birthday Party record), though Cave’s opening gambit – ‘Hands up who wants to die!’ – on the thrilling ‘Sonny’s Burning’ was as much a self-parody as anything he could accuse Peter Murphy of.

The Bad Seed had been recorded in West Berlin after the quartet had decamped there two months after Junkyard’s unanimously strong reviews. Though Ivo considers the EP the band’s ‘crowning glory’, the cost of maintaining The Birthday Party overseas was prohibitive. ‘Ivo was disappointed but pragmatic about not being in a position to provide financial support,’ recalls Mick Harvey. ‘That’s when we switched over to Mute. They’d had worldwide hits with Depeche Mode and Yazoo and were pretty cashed up.’

Chris Carr: ‘I think Ivo was miffed, but he realised there was nothing he could do, given the financial structure that Beggars could then cope with.’1

As one band departed 4AD for Germany, taking their testosterone-fuelled fantasies with them, so a band departed Germany for 4AD, bringing a jolt of oestrogen, but with as much energy and discipline. If anyone thought Ivo’s penchant for dark paths had diminished, Xmal Deutschland would make them think again.

Living again in her native Hamburg after several years in New York, Xmal’s founding member and singer Anja Huwe has abandoned music for painting, but she describes herself as a synesthete (a stimulus in one sensory mode involuntarily elicits a sensation in another) who paints what she hears. ‘I had a wonderful time playing music, and achieved everything I wanted,’ she says. ‘But colour is my ultimate music.’ It’s why she turned down the chance to go solo when Xmal Deutschland finally split in 1990. ‘Music was art to me; I didn’t want to be a pop star,’ Huwe says. ‘I knew the price would have been me. It’s why 4AD was perfect at the time. I saw it as a platform or a nest. People there understood what we did.’

Huwe was destined to be a model, but she turned down an offer to move to Paris when she was seventeen after visiting London in 1977 and seeing The Clash and the all-female Slits at the London Lyceum. ‘The bands were our age, whereas even Kraftwerk felt like old guys to us,’ she recalls. ‘I also saw Killing Joke and Basement 5 on that trip, bands that had this fantastic mix of punk, ska and reggae. I started buying this music, cut my hair very short, and started seeing every band I could in Hamburg.’

The original Xmal Deutschland line-up had joined forces in 1980. ‘We weren’t in either punk or avant-garde camps, and we had a keyboard. No one could label us,’ says Huwe. That didn’t stop the German press from trying: ‘We were repeatedly told we sounded more British than German. A friend recommended we move to London, which wasn’t meant in a nice way. But we thought, why not?’ Once there, their black garb, nail varnish and song titles such as ‘Incubus Succubus’ (the second of two singles that had been released in Germany) had Xmal tagged as goth. ‘That drove us nuts. The Sisters of Mercy, The Mission – that all came later.’

A foothold in London was established after sending 4AD a rehearsal tape. ‘It was the label we wanted, because of Bauhaus and The Birthday Party,’ says Huwe. ‘Our English wasn’t that good, and we were aliens really. But Ivo respected what we did.’

Ivo says he had instantly enjoyed what he heard: ‘They were boiling over with energy, and Manuela Rickers was an incredible, choppy rhythm guitarist. I flew to Hamburg and agreed to an album.’

Xmal Deutschland became 4AD’s first European act, but didn’t record anything until their line-up settled on Huwe, Rickers, Scots-born keyboardist Fiona Sangster, new drummer Manuela Zwingmann and the first male Xmal member, bassist Wolfgang Ellerbrock. The German contingent found London a marked contrast to Hamburg, where people had ‘health insurance, affordable apartments and heating’, says Huwe. ‘Many British bands we met were very poor, and desperate for success. I spent a summer with Ian Astbury [frontman of Beggars Banquet’s similarly goth-branded Southern Death Cult), spending his advance. He’d say, I will be big one day, a pop star, and he did everything he could to get there. That wasn’t our goal.’

That was clear from Huwe’s decision to sing almost entirely in German, which she saw as a much harsher language than English and which suited the band’s pummelling mantras and Huwe’s chanting style. ‘I was like Liz Fraser,’ she recalls. ‘British audiences couldn’t understand us! But they got the spirit of it. Ivo sometimes asked what I sang about. Oh, this and that, I’d reply! Relationships, loneliness, emptiness … what young people sing about. But I saw my voice as an instrument and myself as a performer, not a songwriter. The performance and the sound was the most important.’

Xmal Deutschland’s debut album Fetisch – ‘a word in both German and English, and a word of the time,’ says Huwe – was a faster and harsher take on the cold, black steel of Siouxsie and the Banshees, Joy Division, Mass and In Camera. John Fryer engineered the session at Blackwing, where Ivo was again co-producer with the band, but the album could have sounded less dense and flat. ‘I did them a disservice by producing,’ Ivo reckons. ‘I don’t take all the blame, as John wasn’t the best at that time at micing up a drumkit, which then hinders positioning the guitars around it.’

On stage, Xmal was freer to pull out the stops. The memory of the band’s debut UK show, opening for Cocteau Twins at The Venue, is etched in Ivo’s memory: ‘I’d never seen an audience, clustered around the bar, run so fast to the front of the stage when Xmal plugged in. You could see the audience think, who are these women? They looked really striking.’

Both bands set off on tour, sharing a base in London. ‘Because of their Scottish accents,’ says Huwe, ‘only Fiona could understand a word they said – and the other way around too!’ Xmal later supported Modern English. At that time, Huwe says, ‘4AD felt like a family’.

Oliver expanded the 4AD family by briefly dating Xmal drummer Manuela Zwingmann, who Ivo says he alienated by hiring a Linn drum machine for his lengthy remix of Fetisch’s opening track ‘Qual’. ‘What Manuela played on Fetisch was fantastic, but she struggled to get good takes, and the drum sound was the weakest part,’ he feels. Ivo’s remix remains his favourite Xmal recording, though at the Venue show, Ivo recalls John Peel DJing between sets: ‘After he played the “Qual” remix, he said, “That’s another interminably long twelve-inch single”. And he was right.’

The Qual EP was still fronted by the original album version, but longer remixes were to become a permanent fixture of singles and EPs, as the newly expanding synth-pop, New Romantic and electro sounds accentuated the dance element across both mainstream and alternative scenes, leading to an increase in club audiences and more specialist radio stations. Post-punk’s monochrome palate was slowly receding. Even a resolute rock band such as Xmal got the twelve-inch remix treatment. The apotheosis of the medium was New Order’s single ‘Blue Monday’, released in March, which was to become the biggest selling twelve-inch single of all time; it had only been just under three years since Ian Curtis died, but Joy Division felt like gods from a past age.

At least the twelve-inch format gave Vaughan Oliver the opportunity for a larger canvas for singles. Ivo encouraged every 4AD signing to use the services of 23 Envelope, as it made both artistic and financial sense. The finished image might result from Oliver’s interpretation of a demo or a finished track – for example, his book of medical photographs for ‘Qual’. However, Nigel Grierson was responsible for the layout of Cocteau Twins’ new single ‘Peppermint Pig’, as well as the photo of a woman (shot from behind, submerged in water) in an outdoor Swiss spa bath. ‘That was more for the texture of the hair and the soft misty feeling,’ Grierson explains. ‘I can’t recall why the band chose it. Maybe they didn’t have much input.’

Robin Guthrie approved of the image for the single, but not the music. The Cocteaus had accepted Ivo’s suggestion of taking on, in Guthrie’s words, ‘a pop producer’. Alan Rankine of The Associates was dispatched to Blackwing. ‘That was a huge mistake,’ says Guthrie. ‘Alan just sat at the back and read magazines. I did all the work.’ Guthrie also claims that Ivo suggested the band ‘write something upbeat for a single’. According to Guthrie, ‘We had a tour coming up supporting Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark and we needed a record out. “Peppermint Pig” is absolutely terrible, but we didn’t have the strength of character to wait for the right song to come along. It was an early indication of the power of the music industry, and of too many cooks.’

Contrary to Guthrie’s view, Ivo recalls he was very happy with the single, though says it does sound too much like The Associates. ‘But if I was interested in a “pop” producer, I’d have chosen someone like Mike Hedges [who had produced The Associates’ 1982 masterpiece Sulk]. I know Robin wasn’t happy with the single but it’s silly to suggest that I was trying to commercialise their music. It’s not my interest or one of my strong points. But accepting a producer actually did Robin a favour. By imposing myself on Garlands and Lullabies and then foisting Alan Rankine on them, he was so pissed off that he took control from then on.’

‘Peppermint Pig’ was only kept off the top of the independent singles chart by ‘Blue Monday’. But it’s easily Cocteau Twins’ least memorable single for a good reason: none of its assets – the melody, the production, the cover – are special. That all was not right in the band’s camp was underlined by the departure of Will Heggie. The OMD tour had been fifty-two dates long, a huge number for an inexperienced band such as Cocteau Twins, and the bassist left the band as the band itself left the tour two shows before the end. Guthrie says it was Heggie’s decision: ‘Maybe he had more integrity than me. He didn’t want to tour that much, or to move away from Scotland as we had planned.’

Ivo also suggests that Elizabeth Fraser felt Heggie had come between her and Guthrie, while Guthrie wonders if Heggie was himself keen on Fraser. Ivo only knows for sure that it was Guthrie and Fraser’s choice, and that he was asked to tell Heggie. ‘They all returned to London, but only Robin and Elizabeth stayed with me. I remember Liz doing some ironing in the living room when they said they no longer wanted Will involved. The next day, he and I met at Alma Road.’

‘I didn’t know that,’ says Guthrie. ‘To my knowledge, Will said he was going home – and I’d suddenly lost my best mate, so what the fuck’s happened there? But every cloud has a silver lining, because that’s when Cocteau Twins started to really happen for me.’

By bringing the core down to two members, Guthrie and Fraser closed ranks to create a strong unity and, it seems, more confidence. That touring had meant a dearth of new material only inspired the pair. As Guthrie recalls, ‘We were in a chip shop, unable to eat because of the speed we’d taken, and Liz said, “Let’s make the next album, just the two of us, get money off 4AD and say we have lots of songs, and then produce it yourself.” We wrote it all in the studio, and everything just fell into place. It felt like the chains had been taken off.’

It was still a big step to allow Guthrie to take charge, so Ivo sent John Fryer up to Palladium to assist. ‘John and Jon [Turner] were happy to play pool and let Robin get on with it,’ says Ivo. ‘This is where his courage to do these huge reverbs first appeared.’

‘I’d leave Robin on his own, and if he needed help, obviously I was there,’ Turner recalls. ‘Liz was another story. She had to be in the right mood to sing, so it was better if I walked out. I’m amazed how it all came together. I was used to people knowing exactly what they were doing, and on what budget, but I learnt from the Cocteaus that it doesn’t matter how you get there, the end result is what counts, and they got great results. But it seemed a stressful way to work if you were in a relationship.’

Ivo also felt that Colourbox needed objective input, enlisting Mick Glossop (whose post-punk CV included PiL) for a re-recording of both ‘Breakdown’ and ‘Tarantula’: ‘The band wanted another go, and we thought it was worth using a successful producer,’ Ivo explains. If this was a step up, it was also a worrying step; didn’t Colourbox have new songs they wanted to record?

Martyn Young was more interested in perfecting the editing tricks he’d heard from the pirate radio tapes that Ray Conroy and Ivo had started to bring back from trips to New York. ‘These incredible mixes, which would sound nothing like the twelve-inch single,’ says Ivo. ‘Nowadays, you press a button and it’s done for you, but back then, you’d bounce down fifteen snare hits and edit them together to get a repeat sound. Mick [Glossop] and John Fryer would do the actual cuts amazingly fast, with Martyn to guide them, but he became an incredible editor.’

The new ‘Breakdown’ (‘Tarantula’ was only remixed in the end) wasn’t radically different, just sharper and fuller. The single even got interest from the States. Before the licence deal with major label A&M, Ivo had been exporting every 4AD record, in limited numbers. This helped financially but also built an aura of enigma for this UK imprint with the atmospheric underground sound and artfully enigmatic sleeves that rarely featured the artists. Who were these bands? What was their story?

Ivo’s introduction to major label culture had not been auspicious. A&M in America was already licensing Bauhaus from Beggars Banquet, so Ivo had accompanied Martin Mills to a meeting. ‘Martin introduced me as 4AD, Bauhaus’ original label, and the A&M guy said, “Listen to the radio, get an idea of what works here or doesn’t.” It turns out he thought I was Kevin Haskins. I gave him copies of “Breakdown” and by the time I’d got to the airport, Martin had paged me to say A&M told him they had to license “Breakdown”. Yet they never again licensed anything by Colourbox.’

A&M would have clocked a cool-Britannia take on American influences – a winning combination. But neither A&M nor 4AD had any success with ‘Breakdown’, though the twelve-inch mixes went down well in the clubs, where the edits came into their own. After a period that might be kindly referred to as ‘research’, Gary Asquith and Danny Briottet were to begin their own dance project, mixing hip-hop, sampling and electro as Renegade Soundwave, with Mick Allen and Mark Cox closing ranks as a duo to become The Wolfgang Press, named after German actor Wolfgang Preiss. ‘We added “The” to the front, which conjured up an image, something massive, a big machine,’ says Allen. ‘I thought it was funny.’

Ivo had agreed to go halves on funding new Allen/Cox demos, and on the evidence of two songs, ‘Prostitute’ and ‘Complete And Utter’, asked for more. It was partly an altruistic act, and one of faith: ‘I liked Mick and Mark so much, I wanted to support them,’ Ivo says. ‘They were the only people ever on 4AD I worked with that wasn’t just based on enjoying their music.’

Mark Cox: ‘I never asked Ivo how many records Mass had sold. He was slightly frustrated, almost dismayed, that we had no ambition and were still asserting our right to be free. Compare that to Modern English – they had a dream that Ivo could relate to, but he wasn’t sure what to do with us. We weren’t interested in playing live, and we lived in short-life housing with no phone, so things could take days or weeks to happen.’

Mick Allen: ‘Rightly or wrongly, we were left to our own devices because Ivo had confidence in us. I wanted to make music that you hadn’t heard before, although drawing from the past. I was aware of PiL, the bass and the drums and the simplicity and the space, and I think we achieved that.’

The PiL comparison was to dog them: NME claimed The Wolfgang Press’s debut album The Burden Of Mules could be marketed as a collection of PiL studio out-takes. But freed from accommodating a guitarist at the start, Allen and Cox had begun to explore a wider remit, sometimes gravitating towards a mutant funk that unfolded through a shifting landscape, as though Mass had opened the doors and let in some light and air. But the mood was still oppressive, such as the opening and typically provocative ‘Prostitute’ (‘Prostitute/ Spice of life’) with Allen’s slightly creepy delivery, while the title track – too closely – tracked the ‘death disco’ aura of PiL. ‘Complete And Utter’ wore more urban-tribal colours but ‘Slow As A Child’ was six minutes of unsettling and shifting ambience, and ‘Journalists’ (a soft target, though Allen says his lyric was aimed at anyone in his path) and the ten-minute finale ‘On The Hill’ were as uncomfortably intense as the Mass album.

Ivo still wasn’t won over. ‘It’s a very difficult record and I didn’t like it deeply at all. Like Mark said about Labour Of Love, it had great ideas, badly executed.’

Cox: ‘We were still determined not to be produced, or to be open to guidance in case it meant compromise. But we still didn’t know how to achieve our aims.’ Even so, the duo had agreed with Ivo’s suggestion to add some guitar, and to use In Camera’s Andrew Gray – they had all met when Mass and In Camera had shared bills in London and Manchester – whose oblique approach fitted their own better than Marco Pirroni or Gary Asquith’s heavier style. Dif Juz drummer Richie Thomas and In Camera’s David Scinto (on drums, not vocals) also chipped in.

Gray also signed up for a handful of Wolfgang Press shows, supporting Xmal Deutschland. Allen says it was a frustrating experience: ‘We were not easy listening. It affirmed what we were doing was either bad or unheard.’ Gray soon stepped down. ‘The crowds wanted a particular industrial punk sound, and I didn’t. I’d become more interested in photography at that point.’

Ivo: ‘My take on Mass, The Burden Of Mules and the first live experience of The Wolfgang Press is that people were scared away from them for life. It was impenetrable to some, a different type of music.’

While the nocturnal sounding The Wolfgang Press had been recording an album during the cheaper night shift at west London’s Alvic Studios, Modern English had been taking the daylight shift for parts of After The Snow’s pop levity. The band hadn’t had much success in Britain but the album had been licensed to America by Warners subsidiary Sire. Seymour Stein, the label’s savvy and experienced MD, claims to have been the first to re-appropriate the cinematic term ‘New Wave’ for the new breed of bands after he’d felt that the punk rock tag was putting people off before they’d even heard the music. He had signed the Ramones, Talking Heads and The Pretenders, and after snapping up an unknown local singer called Madonna, he had turned his attentions back to the UK and added Modern English to his stable of UK licensees (The Undertones, Depeche Mode, Echo & The Bunnymen), to be joined by The Smiths.

Stein was especially keen on Modern English’s ‘I Melt With You’. ‘I knew within the first eight bars that it was a smash, it was so infectious and strong,’ he recalls. ‘I also knew I had to grab the band there and then, without hearing any other songs, or someone else would take them. Other things Ivo signed were too experimental for me, though you could always expect the unexpected from 4AD.’

Ivo’s A&R ears weren’t attuned to unearthing or spotting hits, though his brother Perry Watts-Russell – now working as the manager of the fast-rising LA band Berlin – says he’d instantly recognised the value of ‘I Melt With You’. ‘It struck me as really catchy and a definite hit, which didn’t sound much like 4AD but could take 4AD into a different space.’

Modern English had played just a handful of US dates in 1981, and when After The Snow was initially on import, Sire had licensed ‘I Melt With You’ at the end of 1982, becoming the first 4AD track to be licensed in America. Sire followed it by licensing the album in early 1983 when the band returned for an east coast tour. But the breakthrough turned out not to be via a show, or even radio, but a film soundtrack. Stein secured ‘I Melt With You’ a spot in what became that spring’s rom-com film smash Valley Girl, and MTV began rotating the video despite its alarming absence of merit. American audiences simply saw Modern English on a par with Duran Duran, without any of the post-punk image baggage that might have been hindering them in the UK. ‘It all went haywire from there, in a Beatles and Stones way, with all the trappings that went with it,’ says Robbie Grey. ‘We played Spring Break in Florida to thousands of kids going bananas.’

Ivo: ‘I had the bizarre experience of seeing Modern English one afternoon, with screaming girls throwing cuddly toys at them. The band’s name moved to the top of the film poster when “I Melt With You” kept selling.’

The single reached 78 in the national US charts in 1983, with After The Snow making number 70 and also selling half a million. But the breakthrough could, and should, have been even greater. ‘Warners didn’t open their cheque book to help move things to the next level,’ says Ivo, ‘such as the top 40. “I Melt With You” is still one of the most played songs ever on American radio.’

For Modern English, the joy of popularity was tempered by the reality of where they’d landed. ‘We played San Diego baseball stadium to 60,000 people, with Tom Petty top of the bill,’ recalls Mick Conroy. ‘The change was immense and the pressure got insane. Ivo hooked us up with an American manager, Will Botwin, who gave us practice amps, and said to start writing the next album, between gigs. It was so different to 4AD’s approach.’

That didn’t stop 4AD from joining in marketing the band, with a view to breaking them further. As Sire did in America, 4AD released ‘Someone’s Calling’ in the UK, its first attempt to take a single from a preceding album – though the twelve-inch version had a new, booming remix by Harvey Goldberg and Madonna associate Mark Kamins – and a similarly amped ‘Life In The Gladhouse’ remix by Goldberg and Ivo with additional edits from Martyn Young. The latter was a reasonable success in American clubs but ‘Someone’s Calling’ reached a miserable 43 on the UK indie chart, barely higher than ‘Swans On Glass’ three years earlier.

One thing Modern English did achieve was a knock-on shift in profile for 4AD. Even legendary Asylum and Geffen label head David Geffen, who had worked with several of Ivo’s American west coast icons, ‘was sniffing around, wondering what the story was,’ says Mick Conroy. The story for Modern English turned out to be a typical one, of success breeding pressure. Tour manager Ray Conroy was the first to bail. ‘I’m very cynical about arrogant singers – once they start believing it all, it’s not worth the bother,’ he explains. ‘Nick Cave, for example, I found full of shit. And Robbie turned into an asshole. We had a flaming row in New York, and when we got home from America, they went off on their merry way.’

Robbie Grey: ‘We were pushed too hard. I especially didn’t like soundchecks, standing around for hours, only to go on stage and the sound would be all different anyway. I was probably snappy and distant, but I was in my own cocoon, protecting myself.’

Ray Conroy was now tour-managing any 4AD band that required help, such as The Wolfgang Press, Xmal Deutschland and Dif Juz, but he singles out Cocteau Twins as the stand-out live act of the time, even without Will Heggie. ‘Robin had just one guitar pedal and a drum box, but as they got more popular, he got the biggest FX rack ever! It was pretty raging stuff, with Liz screaming her head off. Robin loved noise and our mission was to make them the loudest band in the world.’

The personnel of Modern English and Cocteau Twins became entwined in a project of Ivo’s instigation. He had flown over to see Modern English play New York’s The Ritz in December 1982, where the band’s encore conjoined two tracks, the ‘Gathering Dust’ single and Mesh & Lace cut ‘Sixteen Days’. Ivo liked the version enough to ask the band to re-record it in that segued form, but they turned it down: ‘We were more interested in recording our new material,’ says Mick Conroy.

Trusting in his own judgement, and in John Fryer to press the right buttons, Ivo decided to create his own version. He asked Elizabeth Fraser to sing ‘Sixteen Days/Gathering Dust’ accompanied by Cocteaus’ pal Graham Sharp, who had sung the high, delicate vocals on the band’s second Peel session and was now fronting his own band, Cindytalk (Sharp now likes to go by the first name of Cindy). Martyn Young and Modern English duo Mick Conroy and Gary McDowell were on hand to create the backing track. ‘Ivo was so much into music and creativity that it seemed a natural step for him,’ says Conroy.

Ivo: ‘I loved the experience of affecting the sound of a record, but it wasn’t my place to impose anything. I couldn’t play music and I wasn’t technical. So I needed to create a situation where people gave me sounds that I could have ideas about, that could be manipulated in the studio.’

With Sharp woven around Fraser’s lead, the vocals had power and presence, but the speed of the recording and Ivo’s inexperience of direction showed in the stiff and overlong (at nine minutes) result. ‘The programming is boring and I’d rather forget about it,’ Ivo says. ‘But obviously I thought it was good enough at the time to release as a single.’

Ivo now needed a B-side. He had a brainwave: to conjoin his new vocal crush, Fraser, with the song that Ivo had told the pro-4AD American fanzine The Offense Newsletter ‘was probably the most beautiful song ever written by anybody’, and to UK music weekly Melody Maker, he said, ‘[It’s] probably the most important song ever … it’s moved me more than anything.’

Today, Ivo still holds the track, and the singer, in the same regard. ‘If anyone wanted to demonstrate what’s so special about Tim Buckley,’ he says, ‘I’d play them “Song To The Siren”, because he soars. His voice is the closest thing to flying without taking acid or getting on a plane.’

Though he had first recorded ‘Song To The Siren’ in 1968, Buckley didn’t release a (re-recorded) version until 1970, after being stung by a comment poking fun at the song’s lyrics, written by his writing partner Larry Beckett. In either incarnation, ‘Song To The Siren’ had that uniquely, uncannily eerie lull, using metaphors of drowning to allude to what Ivo calls, ‘the inevitable damage that love causes’.

Fraser agreed to record Buckley’s ballad a cappella, and Ivo gave her a tape of his version so that she could familiarise herself with it. ‘Liz never went anywhere without Robin at that time, so he came along to the studio too,’ says Ivo.

This turned out to be a godsend for Ivo. ‘I couldn’t think of what to do between the verses,’ he recalls, ‘so Robin had, very reluctantly, put on his guitar, found a sound, lent against the studio wall looking decidedly bored, and played it once to Tim Buckley’s version in his headphones.’ He, Guthrie and John Fryer sat in the garden as Fraser – who hated being watched, worked out what to sing.

Ivo: ‘I couldn’t bear the suspense so I crept back inside and listened to what she was doing! I probably only heard her sing it once before I let her know I was there and thought what she was singing was brilliant. But because I couldn’t make the whole thing work without any instrumentation, and because what Robin had spontaneously done was so gorgeous, it was easy to forget my original a cappella idea. Three hours later, the track was finished. I tried to think of ways of taking away the guitar, but I just couldn’t get away from that swimming atmosphere, which is a tribute to Robin’s genius.’

John Fryer: ‘A-sides of singles can involve tension and stress but B-sides like “Song To The Siren” have less pressure on them. This was one of those times, and the B-side totally outshone the A-side.’

Bucking the trend of cover versions paling in comparison to the original, this new ‘Song To The Siren’ was exceptional, casting its own and equally haunted spell. ‘Buckley got so close to the edge of a loneliness and yearning that’s almost uncomfortable and stops you in your tracks, whereas Fraser’s version floats in your ears and washes over you, like the sea that’s constantly represented,’ reckons singer-songwriter David Gray (who covered ‘Song To The Siren’ in 2007). ‘Each time I hear either version, I’m transported somewhere else, outside of myself.’

‘Jesus Christ, I made that happen!’ was Ivo’s reaction. ‘And I wanted to do more.’

On the same September day in 1983 as Modern English’s ‘Someone’s Calling’ and Xmal Deutschland’s re-recorded version of ‘Incubus Succubus’ – prosaically called ‘Incubus Succubus II’ – 4AD released a twelve-inch of ‘Sixteen Days/Gathering Dust’. An edited version on the seven-inch became the B-side to the lead track ‘Song To The Siren’. The name that Ivo gave to this collective adventure was This Mortal Coil, a phrase that had originated in William Shakespeare’s most famous play, The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, whose themes centred on treachery, family and moral corruption. The play’s most famous speech, beginning with ‘To be or not to be’, contained the lines, ‘… what dreams may come/ When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, must give us pause.’

The word ‘coil’, derived from sixteenth-century English, was a metaphor for trouble, or in the Oxford English Dictionary’s view, ‘the bustle and turmoil of this mortal life’. Not being academically minded, Ivo hadn’t known the provenance of the phrase; his source had been Spirit’s 1968 track ‘Dream Within A Dream’, specifically the line ‘Stepping off this mortal coil will be my pleasure.’

‘This Mortal Coil somehow suited the music,’ Ivo explains. ‘I didn’t take long to decide. I can’t say I still love the name, but I became comfortable with it.’

Less comfortable with the affair was Fraser, who was mortified to discover after the recording that she’d got a lyric of ‘Song To The Siren’ wrong. The promised sheet music from the publishers had never arrived, so she’d tried to decipher the words from Buckley’s version. ‘A few mind-bending substances were involved along the way,’ recalls Sounds journalist Jon Wilde, whose flat Fraser and Guthrie stayed in for several months. ‘By the time they had to go to the studio, one line continued to elude us.’

Fraser eventually sang, ‘Were you here when I was flotsam?’ instead of the correct line, ‘Were you hare when I was fox?’ which was an understandable error given the context for Beckett’s lyrics was water and not earth. The mistake compounded Fraser’s already self-conscious view of her performance; she’d felt rushed into the recording and was unhappy with what she’d achieved. But this was just for a B-side so it she let it pass.

The NME, while featuring Depeche Mode on the cover, buried its review low down on the Singles page, citing, ‘a respectable job on “Song To The Siren” and that’s about it – no revelation’. But if the leading UK music paper was still being sniffy about 4AD (The Burden Of Mules had been reviewed six weeks after release), ‘Song To The Siren’ entered the independent chart, and Fraser and Guthrie were asked to perform it live on BBC TV’s late night show Loose Talk. ‘I’ve never been more nervous in my life for anyone as I was for Liz that day,’ says Ivo. Fraser was visibly shaky but still cut a mesmerising figure.

The duo also agreed to make a video, and by the end of its run on the UK independent singles chart, ‘Song To The Siren’ was to rack up 101 weeks, the fourth longest ever in indie singles chart history, behind Bauhaus’ ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead’ (131 weeks), New Order’s ‘Blue Monday’ (186 weeks) and Joy Division’s ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ (195 weeks). ‘Song To The Siren’ also reached number 66 in the UK national charts, selling in excess of half a million copies, without the film soundtrack or major label marketing that had launched ‘I Melt With You’.

Only a reissue of Bauhaus singles on the 4AD EP separated the release of ‘Song To The Siren’ and new Cocteau Twins records, which had been recorded before the This Mortal Coil sessions. Having had one-off contracts for Garlands, Lullabies and Peppermint Pig, the band had signed a contract for five albums, or to run five years, whichever condition was fulfilled first. Colourbox signed the same kind of deal. ‘Both bands wanted a wage and I thought they deserved a certain standard of living,’ says Ivo. ‘I also wanted to carry on working with them. We all recognised we were part of something that was becoming quite special.’

Cocteau Twins’ second album Head Over Heels was released at the end of October, followed just one week later by the EP Sunburst And Snowblind, a collective hit of newfound freedom, expressed in a lush, panoramic drama that far exceeded Garlands’ stark origins. The album cut ‘Sugar Hiccup’ also fronted the EP with an equally new-found commerciality, while the album’s serene opener ‘When Mama Was Moth’ further extinguished all convenient Banshees and goth comparisons. Equally, ‘Glass Candle Grenades’ fed in a graceful, rhythmic imagery and ‘Musette And Drums’ was a magnificent finale.

Ivo: ‘Robin and Liz’s relationship and their music had just blossomed. Head Over Heels showed an extraordinary growth, especially Elizabeth’s singing. The Peel session recorded shortly after includes my favourite ever Liz vocal, in the version of [Sunburst And Snowblind cut] “Hitherto”. It’s the track I play people if they’ve never heard Cocteau Twins. She sounds completely unfettered and it still gives me shivers.’

If Cocteau Twins could magic this up on the spot, what could they do with a little planning? Part of the music’s magic was down to the euphoria between the duo, bound up in the album title’s expression of love and Fraser’s new engagement ring. ‘We were young and in love,’ Guthrie recalls. ‘We’d just moved to London, people were saying how great we were, which fuelled us. As did loads of speed!’

23 Envelope mirrored Cocteau Twins’ huge pools of reverb with a silver-metal pool of ripples (inspired by a key scene in Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 film Stalker) and a fish disappearing, stage right, from the photo. ‘That was a mackerel,’ Nigel Grierson explains, ‘in coloured ink, in a bath of water, into which we’d thrown flower petals. Everyone at 4AD went nuts over the image, and from there, we were directing operations more, trying to create a connection between the music and the visuals, without narrowing the interpretation, but to let the imagination work.’

Yet Guthrie again didn’t find 23 Envelope’s choices suited his own image of the band. ‘Some of Nigel’s other photos were joyous and beautiful but the one they chose was dark, dull and ugly. We’d say what we didn’t like, but they still did what they wanted. We had this joke, that Vaughan put fishes on everything, and we’d say, “No fish!” So I think he’d put it on there to piss us off. But I liked the Sunburst And Snowblind cover.’

Guthrie also resented the sleeve credits. ‘John Fryer only came in towards the end and listened to the mixes, but got a co-producer credit, which I didn’t know until I saw the sleeve. Best of luck to John and I’m sure he got some work out of that, but he had nothing to do with it.’

His mood would have lifted when John Peel played all of side one of Head Over Heels, and all of side two on the following night’s show. Like ‘Peppermint Pig’, the Sunburst And Snowblind EP fell just one place short of topping the independent chart, while reaching 86 in the UK national chart. But Head Over Heels was 4AD’s first record to top the indie charts, and only fell one place short of the UK national top 50. This wasn’t Depeche Mode-level success, but it added to 4AD’s tangible sense of arrival.

If would be a perfect end to the year if Colourbox could make similar advances. At least the new EP, called Colourbox, had a new direction: Ivo knew Martyn Young’s reggae/dub predilections and had suggested reggae specialist Paul Smykle as a producer. New singer Lorita Grahame was a reggae specialist too, in the ballad-leaning area of lover’s rock, despite the band’s advertising for a soulful singer. Grahame had a more expressive soul than her predecessor Debian Curry, but she didn’t have enough to bounce off apart from ‘Keep On Pushing’.2 The problem was, Young’s obsessive edits and mixes were wearing down the sonic quality of the music. ‘Nation’ had a memorably funky synth-bass riff but it had been as arduous to make as it was to listen to, at ten minutes long.

‘Some tracks were created with three Revox machines, cutting and pasting sound from the TV, which pre-dated sampling,’ Ray Conroy recalls. ‘One track might take three days, chopping it about. Martyn was so anal at getting it finished. But Ivo gave them a lot of time and space.’

‘The record was a real hotchpotch,’ Ivo concludes, ‘and not the most likely thing to progress their visibility and popularity.’

The EP cover wasn’t designed to make it an easy sell, and the fact it didn’t create a stir showed Colourbox’s low profile. Among fans, the Colourbox EP was known as ‘The Shotgun Sessions’ after the lead track, but also ‘Horses Fucking’ after the chosen image, a photo (in reversed negative, so that the horse’s red penis turned green) taken by Vaughan Oliver years earlier while working a glamorous summer job at a local sewage works. In a manner more befitting a provocateur like Mick Allen, Colourbox had requested ‘something revolting’, says Oliver, who was encouraged by the EP song title ‘Keep On Pushing’. From the pretty horses on After The Snow to the rutting equine couple on Colourbox, Oliver could never be relied on, he says, ‘to take the easy road. I like to provoke, to be perverse.’

‘We thought the cover was funny,’ recalls Martyn Young. ‘You could discuss things with Vaughan, and then he’d go and do his own thing, but they were better than our ideas.’

It was a temporary lull in a year that had seen 4AD on an upward trajectory that climaxed with Cocteau Twins’ first American visit, playing two shows in New York interspersed with a show in Philadelphia on New Year’s Eve, ‘to about twelve people in the audience,’ recalls Ivo, who flew over to celebrate. In the heat of excitement, he even suggested he could manage the band, and give up 4AD in the process: ‘I was so proud to be involved with them,’ Ivo recalls. ‘I felt total commitment. I’m truly grateful they never responded to that particular idea!’

In the meantime, there was a shared sense of love, pride and excitement – and tour profits to revel in: ‘I have a picture of Ivo with three grand in his hand!’ Guthrie grins. Grangemouth and Oundle would have felt a long way in the past.

Another band in the giddy heat of ascendancy was The Smiths, who happened to be on the same New York flight as the Cocteaus, to make their own US debut. But Smiths drummer Mike Joyce fell ill and had to return home after one show, so their dates were cancelled. At a consolation party in promoter Ruth Polsky’s tiny New York apartment, Guthrie recalls, ‘being cornered in the kitchen by Johnny Marr – a lovely guy but all he wanted to talk about were Rolling Stones records! I was more, “OK, let’s have more drugs!”’

1 The Birthday Party turned out to only have one more EP left in them, the four-track Mutiny, which, in 1989, Mute allowed 4AD to add to the CD reissue of The Bad Seed, ensuring that every Birthday Party release did end up on 4AD. Mutiny rang the changes for The Birthday Party as Rowland S. Howard didn’t turn up for sessions and Einstürzende Neubauten’s Blixa Bargeld stepped in on guitar, lending a more controlled, less jagged aura to the sound. Harvey confirms that communication between Cave and Howard had broken down, and the band had ‘no new direction’. Even before Mutiny had been released, Harvey had proposed the band split up; Cave and Howard instantly agreed, paving the path to the formation of Cave’s solo career with his Bad Seeds backing band, which changed over the years but started off with Bargeld, Harvey and Barry Adamson.

2 Without Ivo’s knowledge, Martyn Young had recorded a phone conversation with him, and part of it was spliced into one of the Colourbox EP tracks: ‘It was one of Ian’s,’ Young reckons, which makes it either ‘Nation’ or ‘Justice’. Yet the only audibly sampled phone call appears to be ‘Keep On Pushing’, even though the accent sounds more like Ray Conroy than Ivo. ‘When Ivo found out, he wasn’t pleased,’ Young adds. ‘It’s still on there, but we had to disguise his voice.’