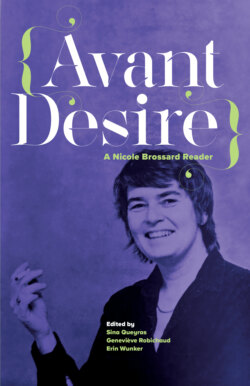

Читать книгу Avant Desire: A Nicole Brossard Reader - Nicole Brossard - Страница 25

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

HOTEL RAFALE

Оглавлениеfrom Baroque at Dawn

tr. Patricia Claxton

First the dawn. Then the woman came.

In Room 43 at the Hotel Rafale, in the heart of a North American city armed to the teeth, in the heart of a civilization of gangs, artists, dreams, and computers, in darkness so complete it swallowed all countries, Cybil Noland lay between the legs of a woman she had met just a few hours before. For a time which seemed a coon’s age and very nocturnal, the woman had repeated, ‘Devastate me, eat me up.’ Cybil Noland had plied her tongue with redoubled ardour and finally heard, ‘Day, vastate me, heat me up.’ The woman’s thighs trembled slightly and then her body orbited the planet as if the pleasure in her had transformed to a stupendous aerial life reflex.

Cybil Noland had felt the sea enter her thoughts like a rhyme, a kind of sonnet which briefly brought her close to Louise Labé, then drew away to pound elsewhere, wave sounds in present tense. The sea had penetrated her while whispering livable phrases in her ear, drawn-out laments, a lifelong habit with its thousand double exposures of light. Later, thoughts of the sea cast her against a boundless wall of questions.

In the room, the air conditioner is making an infernal noise. Dawn has given signs of life. Cybil can now make out the furniture shapes and see, reflected in the mirror on the half-open bathroom door, a chair on which are draped a blue T-shirt, a pair of jeans, and a black leather jacket. On the rug, a pair of sandals one beside the other.

The woman puts a hand on Cybil Noland’s hair, the other touching a shoulder. The stranger at rest is terribly alive, anonymous with her thousand identities in repose. Cybil Noland turns so as to rest her cheek comfortably in the curve of the other’s crotch. Neither thinks to move, much less to talk. Each is from somewhere else, each is elsewhere in her life of elsewhere, as if living some life from the past.

Cybil Noland had travelled a lot, to cities with light-filled curves shimmering with headlights and neon signs. She loved suspense, the kind of risk that might now take as simple a guise as strolling about among the buildings of big cities. She had always declined to stay in the mountains or the country or beside a lake, even for a few days. Her past life had unfolded at a city pace, in the presence of many accents, traffic sounds, and speed, all of which sharpen the senses. Over the years she had come to love sunsets reddened by carbon dioxide. It had been so long since she had seen the stars that the names of the constellations had long ago vanished into her memory’s recesses. Cybil Noland lived at information’s pace. Information was her firmament, her inner sea, her Everest, her cosmos. She loved the electric sensation she felt at the speed of passing images. Each image was easy. It was easy for her to forget what it was that had excited her a moment before. Sometimes she thought she ought to resist this frenetic consumption of words, catastrophes, speed, rumours, fears, and screens, but too late, her intoxication seemed irreversible. Between fifteen and thirty years of age she had studied history, literature, and the curious laws that govern life’s instinct for continuation. Thus she had learned to navigate among beliefs and dreams dispersed over generations and centuries. But today all that seemed far away, ill-suited to the speed with which reality was spinning out her anxiety with its sequences of happiness and violence, its fiction grafted like a science to the heart of instinct. As a child she had learned several languages, enabling her today to consume twice the information, commentary, tragedy, minor mishaps, and prognostications. Thus she had unwittingly acquired a taste for glib words and fleeting images. All she had learned in her youth finally came to seem merely muddleheaded, anachronistic, and obsolete.

On this July night that was drawing to a close in a small hotel in a city armed to the teeth, Cybil Noland had felt the sea rise up and swallow her. Something had spilled over, creating a vivid horizontal effect, but simultaneously a barrier of questions. The sky, the stars, and the sea had synthesized an entire civilization of cities in her when the woman came.

There between the stranger’s legs, questions arose, insistent, intrusive questions, snooping questions, basic questions seeking alternately to confirm and deny the world and its raison d’être. Borne on this current of questions, Cybil Noland vowed to renounce glib pronouncements without however willingly forgoing the dangerous euphoria elicited by the fast, frenzied images of her century.

The light was now diffused throughout the room, a yellow morning light which in movies of yesteryear gave the dialogue a hopeful turn, for the simple reason that mornings in those days were slow with the natural slowness that suited the movements made by heroines when, upon awakening, they gracefully stretched their arms, raising arches of carnal triumph in the air.

The woman has moved her legs to change position, perhaps to leave the bed. Cybil Noland has raised her head then her body in such fashion as to hoist herself up to the level of the woman’s face. The mattress is uncomfortable, with hollows and soft spots one’s elbows and knees sink into.

Since meeting, the two have barely exchanged three sentences. The woman is a musician and young. ‘But I’m not sixteen,’ she said with a smile in the elevator. Cybil Noland thereupon nicknamed her ‘La Sixtine.’ On arrival in the room, they undressed and the woman ordered, ‘Eat me.’

Now that Cybil Noland has the woman’s living face at eye level, her belly swells again rich with desire like a tempestuous wind. Kiss me, kiss m’again.1 With fire and festivity in her eyes, the woman looks Cybil over, caresses her, then thrusts her tongue between her lips. It might have been just a kiss, but what a way she has of breathing, of pearling each lip, tracing abc inside Cybil’s mouth with the tiniest movements, impossible to separate the letters abc, to stop, demon delirium abc a constellation of flavours in her mouth. Then the wind surges, sweeping eyelashes, drying the perspiration about the neck, smoothing silken cheeks, closing eyelids, imprinting the outlines of faces deep in the pillow. The five sibyls of the Sixtine Chapel orbit the planet and the questions return. Cybil Noland opens her eyes. There are still traces of mascara on the woman’s eyelashes. She too unseals her eyes. The look they give is laughing, languid, offering an intimacy glimpsable only in the strictest anonymity. Like a love-crazed thing all of a sudden, Cybil is aburn for this anonymous woman who had caught her eye in the bar of the Hotel Rafale. Something is exciting her, something about the anonymity of this woman encountered in the middle of a huge city, something that says, I don’t know your name but I recognize the smooth curvaceous shape your body takes when navigating to the open sea. Soon I shall know where your tears, your savage words and anxious gestures hide, the things that will lead me to divine everything about you at one fell swoop. Thus does imagination take us beyond the visible, propelling us toward new faces that will set the wind asurge despite the barrier formed by vertical cities, despite the speed of life that drains our thoughts and leaves them indolent. The priceless eyes of desire are right to succumb to seduction so that one’s familiar, everyday body may find joy in the thousands of anonymous others encountered along the way, bodies pursuing their destinies in cities saturated with feelings and emotions.

The stranger gives off a scent of complex life which coils about Cybil Noland. City smells clinging to her hair like a social ego; fragrant, singularizing sandalwood, a trace of navel salt, the milky taste of her breasts. Everywhere an infiltration of life, aromatic, while the child in one does the rounds of all the smells, anonymously like a grown-up in a hurry to get thinking.

The air conditioner has stopped. There’s silence. A surprising silence like the heady smell of lilac when the month of May reaches us at the exits of great, sense-deadening cages of glass and concrete. The silence draws out, palpable and appealing like La Sixtine’s body. The alarm-clock dial on the bedside table is blinking. A power failure. Which means unbearable heat in exchange for a silence rare and more precious than gold and caviar. The silence is now diffused throughout the room. Surprising, devastating. An unreal silence that’s terribly alive, as if imposing a kind of fiction by turning the eyes of the heart toward an unfathomable inner life.

The women lie side by side, legs entwined and each with an arm under the other’s neck like sleepy reflex arcs. Suddenly Cybil Noland can stand no more of this new silence that has come and imposed itself on top of the first, which had been a silence tacitly agreed between them like a stylized modesty, an elegant discretion, a kind of meditative state capable of shutting out the sounds of civilization and creating a fictional time favourable to the appearance of each one’s essential face.

Cybil Noland had brought the woman up to her room thinking of what she called each woman’s essential face in her own destiny. Each time she had sex with a woman, this was what put heart into her desire. She was ready for anything, any kind of caress, any and all sexual scenarios, aware that you can never foresee exactly when, or for how long, an orgasm will recompose the lines of the mouth and chin, make the eyelids droop, dilate the pupils or keep the eyes shining. Most often the face would describe its own aura of ecstasy, beginning with the light filtering through the enigmatic slit between the eyelids when they hover half-closed halfway between life and pleasure. Then would come the split second that changed the iris into the shape of a crescent moon, before the white of the eye, whiter than the soul, proliferated multiples of the word imagery deep in her thoughts. This was how a woman who moments earlier had been a total stranger became a loved one capable of changing the course of time for the better.

All, thought Cybil Noland, so that the essential face that shows what women are really capable of may be seen, vulnerable and radiant, infinitely human, desperately disturbing. But for this to happen, the whole sea would have to flood into her mouth, and the wind flatten her hair to her skull, and fire ignite from fire, and she would have to consider everything very carefully at the speed of life and wait for the woman to possess her own silence, out of breath and beyond words in the midst of her present. In the well of her pleasure the woman would have to find her own space, a place of choice.

So when the air conditioner stopped, Cybil Noland felt she had been robbed of the rare and singular silence that had brought her so close to La Sixtine. As if she had suddenly realized that while the words heat me vast2 were ringing with their thousand possibilities and her delicate tongue was separating the lips of La Sixtine’s sex, civilization had nevertheless continued its headlong course.

Now the new silence is crowding the silence that accompanies one’s most private thoughts. While groping for a comparison to explain this new silence, suddenly Cybil Noland can stand no more of it and wants to speak, will speak, but the woman comes close and reclines on top of her and with her warm belly and hair tickling Cybil’s nose, and breasts brushing over Cybil’s mouth, seems determined to turn Cybil’s body into an object of pure erotic pleasure.

You’d say she was going. To say. Yes, she murmurs inarticulate sounds in Cybil’s ear, rhythms, senseless words, catches her breath, plays on it momentarily, ‘That good?’ she breathes. ‘That better?’ Then over Cybil’s body strews images and succulent words that burst in the mouth like berries. Now her sounds caress like violins. The names of constellations come suddenly to Cybil’s mind: Draco the Dragon, Coma Berenices, Cassiopaeia, and Lyra for the Northern Hemisphere; Sculptor, Tucana, Apus the Bird of Paradise, Ara the Altar for the Southern. Then the whole sea spreads through her and La Sixtine relaxes her hold.

You’d say she was going to tell a story. Something with the word joyous in the sentence to go with her nakedness there in the middle of the room. Once she’s in the shower the water runs hard. She sings. When she lifts her tongue the sounds crowd up from under, full of vim. Joyously her voice spews out, zigzags from one word to another, cheerily penetrating Cybil Noland’s consciousness as she lies half asleep in the spacious bed.

‘I’ll tell you a story,’ La Sixtine said, opening the window before getting in the shower. The window opens onto a fire escape. The curtain moves gently. Cybil Noland watches the movements of the fish, seaweed, and coral in the curtain’s design. Life is a backdrop against which thoughts and memories overlap. Life moves ever so slightly, goes through static stages, skews off, brings its humanism to the midst of armed cities like a provocation, a paradox that makes you smile. In spite of yourself. The dark fish throw a shadow over the pinks and whites of the coral, Cybil Noland thinks before riding off again, a deep-sea wanderer aboard great incunabula.

The power’s back on. The air conditioner’s working. In the corridor, the chambermaids are bustling back and forth again.

When she got out of the shower La Sixtine turned on the radio. A sombre voice entered the room, spreading a smell of war and filth. The voice waded its way through ‘today the authorities’ and ‘many bodies in front of the cathedral, some horribly mutilated. Fetuses were seen hanging from the gutted bellies of their mothers. In places the snow seemed coated with blood. Old women, open-mouthed and staring toward the cold infinity of the region leading to the sea, spoke of human limbs scattered about the ground. Other witnesses talked of hearing the cries of children although no children have been found. At present the authorities are unable to say what group the dead belong to since from their clothing one cannot tell whether they are from the north-east or the east-north.’

One after another the sentences fall to the room’s pink carpet. Cybil Noland watches from the spacious bed. La Sixtine sits on the edge of the bed with a towel about her hips and seems to be breathing with difficulty. Then, as if tired of trying to find her breath, she turns and curls her body into Cybil’s trembling nakedness. Her head weighs heavily. Her body is heavy. The present is a body. The body is a live, pure present that goes on forever between the electrical thrum of the air conditioner and the voice from the radio.

Cybil Noland thinks about the morning she spent in a Covent Garden café. Her head that morning was full of a woman who wants to write a novel. This woman lacks vocabulary to describe the volcano of violence erupting in cities. She is sitting in a large kitchen. While she spoons sugar into her teacup with a little silver spoon, her hair brushes over the sugar bowl. She is young and resolute, in contrast with the fact that she is still in pyjamas at this late morning hour. There is a dictionary on the table. With one hand she holds the silver spoon and with the other absentmindedly turns the pages of the dictionary. She gets up and goes to the window, where for a minute she leans on the sill. From here she can see the approaches to Hyde Park, the texture of the day and the fine rain of this weather that penetrates the very core of one. She gazes into the distance. At the far side of herself, she ponders a fictional life. She observes so meticulously that the pondering fits her head and thoughts like a helmet. A book by Samuel Beckett lies on the table. The sugar bowl looks like a volcano. The woman lives alone, surrounded by ferns and a wealth of other plants to which she will put no names so that in their green anonymity they will create a fine, rich tropical forest for her. The rain falls slowly. She lights a cigarette. Why would she write this violent book? She has no special gift for it, or vocabulary or experience. She puts a hand on the dictionary and draws it close. The hand stays resting on the cover as though she’s about to take an oath. With the other hand she writes a list of violent words, words that turn one’s stomach, turn one’s head to suffering, to people and their progeny who thirst for vengeance. Beyond the window Hyde Park glows, adding to its mystery, offering its trees and green lawns as so many hypotheses that liven vertigo in contemplation of the future. Truth will never come without worry, nor will the illusion of truth. The woman pours herself another cup of tea. Her father’s oak-panelled library is filled with women’s books. Her father’s books are stacked in the north corner of the kitchen. They stand there like three Towers of Babel. Three towers of leather-bound volumes showing their gold-leafed spines.

The fine rain keeps falling and the woman treasures those images of the north that make her homesick. It isn’t memory that does it, it’s this taste of happiness split in two by silence.

Baroque d’aube

1995, tr. 1997