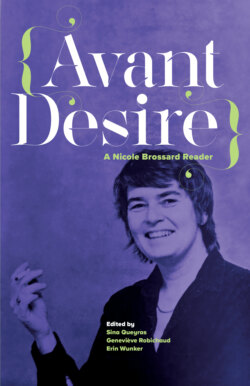

Читать книгу Avant Desire: A Nicole Brossard Reader - Nicole Brossard - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

AVANT DESIRE,THE FUTURE SHALL BE SWAYED

ОглавлениеAn Introduction by

Sina Queyras, Geneviève Robichaud, and Erin Wunker

‘I occupy space in Utopia. I can push death away like a mother and a future.’

In the epigraph above, taken from Picture Theory, the speaker makes a statement that is both factual and futuristic: I occupy space in Utopia. It feels risky even to speak of Utopia when, at the time of this introduction, we see irrefutable evidence of the destructive forces of late capitalism, of heteropatriarchy, of racism and colonialism. None of these structures that fundamentally shape our different lives make space for Utopia, and yet Brossard writes that future into the present. The confidence and power of her speaker is both seductive and generative. Here, in Utopia, the speaker can push death away like a mother, without having to be a mother.

Nicole Brossard’s work is both thrill and balm – and now, in Avant Desire: A Nicole Brossard Reader, readers can encounter the full range and scope of her trajectory. We have worked to curate selections that will be relevant and, we think, exhilarating to new and returning readers of Brossard’s work, and we have moved across genres and through time, not in a linear way but in a way that fits the always-aliveness of her work. If Utopia seems impossible to readers in 2020, Brossard’s work reminds us that when we gather – either on the page reading, or in rooms together – our co-presence conjures the possibility of Utopia.

Over a fifty-year period, Nicole Brossard has published more than forty works of poetry, prose, essays, and non-fiction. She has broken through the bonds of sexual and linguistic repression, and in doing so has reached across several generations and two solitudes to enchant avant-garde, feminist, and academic readers and writers nationally and internationally, creating a radical, complex, and influential body of literature. It is work that never forgets the importance of pleasure, and that never loses hope in the possibility of Utopia. For the scholar Susan Rudy, Brossard’s writing is comparable to Virginia Woolf in being ‘uncompromising’ in its ‘critique of patriarchal reality, unrelenting in her love for women, and unequalled in [its] aesthetic experimentation.’1 Has any other Canadian writer enjoyed the kind of feverish collaboration and translatory attention paid to Brossard? And has any other Canadian writer had the kind of attention that comes not from the established literary complex down but from the ground up? Poets, writers, and translators have taken up Brossard’s work largely as a labour of love. This is quite impressive when you consider that at the core of this fervour is a radical lesbian innovative writer who comes to English only through translation.

Brossard’s work was initially made accessible to non-French readers through her collaboration with the late Barbara Godard. In an interview with Smaro Kamboureli, Godard noted that she, a bilingual feminist academic, was working to create ‘institutional spaces for intellectual work … and especially feminism in the 1980s when it emerged as an academic discipline.’2 Godard translated Brossard’s poetry for a reading with Adrienne Rich for the Writers in Dialogue conference (1978), as well as her editorial work for Room of One’s Own (1978). Then, frustrated with the lack of conversation between feminist writers in English and French Canada, Godard held the Dialogue conference (1981), which was designed to bring together ‘people across language barriers.’3 A similar urge for connection between English Canada and Quebecois writers would push Godard and Frank Davey to create the Coach House Press Translation Series, which ran from 1974 to 1986.4 Brossard’s work was among the first to be published in the series. Godard largely introduced Brossard’s work to readers in English Canada, translating L’Amèr (1977) and in turn introducing her to the writing of continental French theorists such as Gilles Deleuze: ‘I recognized in particular the serial system of Brossard’s diction and its exploration of “surfaces of sense,” of making the textual body a virtual surface for the inscription of desire.’5 The significance of this collaborative moment is striking. Here, Godard underscores not only the labour involved in translating writers from French to English in Canada, she also acknowledges Brossard’s theoretical influence on her own feminist intellectual development beyond national borders. We see, too, the threads of connection woven between a feminist theorist translating a feminist writer-intellectual in the title of the final publication in the Quebec Translation Series (Surfaces of Sense, 1989). Brossard’s work has forged transformative connections between English and French feminist writers in Canada, and beyond.

The fabric of Brossard’s poetics is one that is also, and importantly so, an invitation to a sensory experience. She has been involved in founding editorial projects like La Barre du jour (1965), Les Têtes de pioches (1976), and La Nouvelle barre du jour (1977). She has helped create numerous anthologies (Anthologie de la poésie des femmes au Québec, 1991; Poèmes à dire la francophonie, 2002; Baiser vertige, 2006; and Le Long poème, 2011). She has also been involved in collaborative stage productions and monologues such as La Nef des sorcières presented at the Théâtre du Nouveau-Monde in Montreal in 1976 (translated by Linda Gaboriau and published as part of Coach House Press’s Quebec Translation Series in 1980 under the title A Clash of Symbols), and Célébrations, which was also presented at the TNM in 1979, as well as Je ne suis jamais en retard at the Théâtre d’aujourd’hui in 2015. There is also her most recent multisensory spectacle and collaboration with Simon Dumas, Le Désert mauve, at L’Espace Go in the fall of 2018.

It is hard to oversell the benefits of the kind of space Brossard creates, even as we are in the midst of an exciting feminist publishing renaissance – a space rooted in many particularities of time, politics, aesthetics, and community, but perhaps foremost this space is an example of the potential of what can be created when thinking through language and in relation to others. This is crucial and central to both Brossard’s work and her position as writer and thinker. In addition to those scores of books, there are countless collaborations, including the documentary Some American Feminists (1977), an endeavour between Brossard, Luce Guilbeault, and Margaret Wescott. The collective buoyancy of the feminist moment in the seventies is well captured in the documentary film, which chronicles the uninhibited powers of a feminist utopian imaginary. For Brossard and her contemporaries, establishing a ‘system of feminine values, the movement and strategies of feminine and/or writing’6 became a way of subverting the patriarchal language that occluded them. How can writing, reading, theorizing, and translating be rethought, they asked, and how can language and literature alter or mark one’s presence in the world? Collaborative thinking, utopian thinking, desiring thinking: all these theoretical models matter.

As the writer Lisa Robertson puts it in her introduction to the English translation of yet another of Brossard’s collaborative engagements, Theory, A Sunday (excerpted here), ‘theory was not only an institutional discourse but a manual and testing ground for political revolution.’ It is our hope that this reader will work as both archive and incentive. As an archive, we aim to show Brossard’s artistic and intellectual work both. In turn, we hope that the resonance of her thinking in these texts acts as motivation and material for future revolutions.

Our selection process has been a dynamic one. In addition to working across provincial borders and time zones, we editors have been thinking together across linguistic and lived experiences that differ from each other. We feel this is a strength, and that the dynamism of our process is in conversation with what we see in Brossard’s work. Avant Desire is organized by thematic sections, which we will go on to describe more fully below. Readers will notice the ways in which these sections cross-pollinate. This is both deliberate and inevitable: Brossard has been orbiting and evolving her writerly attention around some key themes. Desirings; Generations; The City; Translations, Retranslations, Transcollaborations; Futures: each of these descriptors hails, for us, some of the central concerns and beautiful obsessions of Brossard’s work.

Readers familiar with Brossard will recognize some key texts from her oeuvre. Mauve Desert, for example, with its feminist innovations on the form of the novel and its translative play is indispensable to new and returning readers. Likewise, the poetic consciousness-raising of The Aerial Letter reminds those of us familiar with her work of Brossard’s ability to intertwine historical reflection on the effects of heteropatriarchy with a buoyant hope in a feminist future we so desperately need, then and now. We have worked to present some of Brossard’s less-known, less-accessible writing, as well as some new translations of her work. Our thinking, throughout this process, has been to highlight the importance of collaboration, of translation, of returning to key themes, images, and concepts over the course of this writer’s life. Readers will encounter some of the compromises we have made, as well. For example, in order to make tangible the discursive nature of Brossard’s translations, as well as her work with translators, we have sacrificed the usual airiness of her layouts in service of more crosstalk. We are confident that our commitment to bringing these particular selections together plots a course full of delicious tributaries for the reader. Our work, which has taken us to archives and libraries, through emails and conversations with each other and with other writers, and, wonderfully, to Brossard’s dining-room table, has led to some joyous discoveries.