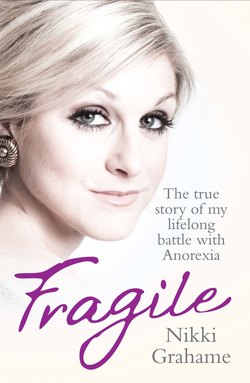

Читать книгу Fragile - The true story of my lifelong battle with anorexia - Nikki Grahame - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THINGS FALL APART

Оглавление‘Will you please stand on your feet and not on your head?’ Mum yelled at me one Saturday morning. ‘You spend more time upside down than the right way up,’ she grumbled.

It was about the millionth time she’d had a go at me about it, half jokingly, half worried I might do myself some permanent damage by spending so much time performing handstands. I’d even watch TV upside down. And when I wasn’t doing that I would be cartwheeling and backflipping my way up and down the wooden floor of our hall.

‘OK,’ Mum finally said, ‘if you love all this acrobatics so much we might as well put it to some use.’ The following week she’d signed me up for the Northwood Gymnastics Club. I was beyond excited. I was still only six years old but getting dressed up in a royal-blue leotard, my long, dark-brown hair pulled back in a pony tail, I felt so important – like a proper gymnast.

All those hours spent on my head had obviously been worth it, because I quickly showed a real ability at gymnastics. And I loved it all – the training, the competitions and just messing around with the other girls afterwards. Cartwheels, somersaults and flips on the mats, vaulting and the asymmetric bars – I couldn’t get enough of it.

Within a couple of weeks the coach must have decided I had some natural talent because I was selected to become part of the gym’s squad.

I was so proud of myself. It was amazing. But being part of the squad instantly meant a lot more pressure. I was representing the London Borough of Hillingdon and there was a gala every six months and a new grade to work for every couple of months. And that meant a lot more training. Within a couple of months this had shot up from gymnastics once a week to sessions three evenings a week and for three hours on a Saturday morning. We’d often do a full hour of tumbling followed by an hour of vaulting. It was exhausting and any sense of enjoyment quickly seeped away.

Being the way I was, I couldn’t be happy unless I was the best in the squad and unfortunately there were girls there who were clearly better than me. One Saturday morning we were in the changing rooms, messing around in our leotards at the end of a tough, three-hour session. One of the other girls was standing behind me, staring at me, when she suddenly said, ‘Haven’t you got a big bum, Nikki?’

I could feel myself going bright red but I just laughed and pulled my shell suit on quickly. How embarrassing.

That evening I crept into Mum’s bedroom when she and Dad were watching telly downstairs. I opened their wardrobe door and stood in front of the full length mirror bolted to its inside.

I analysed my bum carefully. Then I stared at the slight curve of my tummy and then my fleshy upper arms.

Maybe that girl at gymnastics was right – maybe my bum was a bit on the lardy side. Maybe that was why I still couldn’t get those flips right.

After all, that other girl’s arms were much thinner than mine. And she had a tiny bum and virtually no tummy at all and she was brilliant at flips. In fact she was better than me at almost all the routines. Plus, she was really popular with the other girls too.

And I guess that is how it all began. Somewhere in my seven-year-old brain I started to think that to be better at gymnastics and to be more popular, I had to be skinny. And because I didn’t just want to be better than I was at gymnastics, but to be the best, then I couldn’t just be skinny. Oh no, I would have to be the skinniest.

‘I’ll keep my tracksuit bottoms on today, Mum,’ I said as I went into the gym the following week. She didn’t think anything of it then, but I’d decided I didn’t want anyone laughing at my fat bum ever again.

Yet it would be too easy to say that one girl’s catty comments sparked off the illness which was to blight the next ten years of my life and which will inevitably be with me in some way until the day I die.

No, I think that was just what brought things to a head. Looking back, I think I was already vulnerable to any kind of comment that may have been made about my size. Because already a whole truckload of misery was slowly building up behind the front door at Stanley Road.

Dad was having a really rough time at work. Things had always been rocky for him there, but it was getting worse. He kept clashing with his bosses and felt everyone was out to get him. After he joined the union and became heavily involved with it, he felt his bosses were out to get him for being an activist.

‘They’re destroying me,’ I’d hear him rant at Mum.

‘Just keep your head down and stop causing trouble, Dave,’ she would tell him. ‘We need the money.’

But that would just drive Dad into a fury. ‘You don’t understand what it’s like working there,’ he’d rage.

For 18 months he was involved in disciplinary action and subject to reports. It sent him – and all of us – crazy.

Because Dad was convinced he was about to be sacked, he started working part-time at a stamp shop he set up in part of his dad’s jewellery shop off the Edgware Road. So, on top of all the stress at work, he was also working really long hours in his second job, desperate to keep paying the mortgage so we could stay in our perfect home.

He was angry all the time. Looking back, he was probably suffering from depression or stress, perhaps both, but at seven all I could see was that the dad I adored had turned overnight into some kind of raging monster.

In many ways I feel sorry for my dad because he’d had a really tough childhood. He was born in America but at six his father moved to London with a new wife while his mother, Magda, stayed in New York with her new husband. Magda had custody of Dad but, according to the family story, his dad went over there and brought him back to Britain. Having got him back, though, his dad and his new wife realised they didn’t really want him. They didn’t take care of him and he ended up stuck in a children’s home.

Magda still lives in Manhattan in some plush apartment but my dad doesn’t have much contact with her and he doesn’t speak to his father at all. So Dad has had it hard himself in life – he says that’s why he can’t show emotion in front of his kids. But I tell you, he could certainly show anger back then.

And although I can see the reasons for his behaviour now, at that time I was just a little girl who desperately wanted her daddy. And Dad had changed so much – he didn’t want me following him to the betting shop any more and there were no more runs around the streets.

One day I entered a gymnastics competition and won second place. I was so proud of myself and sprinted straight from the gym to Dad’s stamp shop, my silver medal bouncing around my neck as I ran down the road.

I walked into the shop and said, ‘Hi,’ waiting for Dad to notice the shining medal on my chest and to throw his arms around me and tell me how proud he was of his favourite daughter. I waited as he looked up and gave me half a smile over a book of stamps. Then I waited some more. And some more. He didn’t notice, and it was soon obvious he was never going to notice. He hadn’t seen my medal and, worse still, he hadn’t registered the sheer joy on my face. In the end I said, ‘Look, Dad, I came second.’ I can’t even remember how he reacted. Whatever he did or said, that isn’t the bit I remember about that day.

Dad began missing my and Natalie’s birthday parties. And if we had friends round after school and were being noisy he’d go mad. One evening I had my friend Vicky Fiddler round to play. We were busily brushing each other’s hair at the kitchen table when Dad burst into the room in a fury. ‘Who’s this?’ he yelled, glaring at us both. I was devastated he could act so mad in front of one of my friends.

He was always so angry. For as long as I can remember he had called me ‘Fatso’ and ‘Lump’ but it had always seemed like a joke. Now the things he was saying seemed more cruel. He said to Natalie that at night sawdust would fall out of her head on to the pillow because she was so stupid.

At that time Dad was working a lot of night shifts too, which meant Natalie and I had to creep around the house all day, terrified we would wake him up. And when he was on normal day shifts we would skulk around when he was due home, waiting for the sound of his key in the lock, at which point we would run upstairs and hide.

One afternoon we accidentally scratched his backgammon board with my shoe buckle and were so terrified of how he’d react that we spent the entire afternoon hiding in Mum’s wardrobe.

Dad wasn’t violent towards us – although I can remember the odd whack if we were playing up – but just really, really angry. Most of his anger he was taking out on Mum and they were rowing all the time. A lot of their fights happened first thing in the morning when Dad came in tired and grumpy from a night shift and got into bed with Mum. Natalie and I didn’t need to eavesdrop at their door to hear what was going on. We’d wake up and look at each other as we heard every word being hurled across their bedroom. Often it was about stuff I just didn’t understand, other times it was Dad’s problems at work or how we’d keep our house if he didn’t have a job.

As the months went by it felt like they were rowing about everything, right down to what dress Mum was wearing. One time I remember her coming downstairs all dressed up for an evening out. ‘Why are you wearing that?’ Dad said. Mum’s face crumpled and she looked totally lost. ‘You’ve never had any class,’ he sneered at her as she turned around and slowly went back upstairs to change.

I understand now how complicated marriages can be and that there are two sides to every story. And there were probably times when Mum was nasty to Dad or wound him up, but I don’t remember them. I just remember Mum becoming less and less sparkly, less and less pretty and more and more ground down. She stopped having friends round to the house and looked exhausted all the time.

One day I heard Dad tell her she was hopeless and had no vision.

‘You and your family have never thought I was good enough,’ Mum shouted back at him. Mum had been brought up a Catholic and Dad’s family hadn’t liked it, although by this point the two of them couldn’t even agree what channel to watch on the telly, let alone on big things like religion. They never went out the way they had once done and there was no more cuddling up in front of a video.

I was seven and all I wanted was for my daddy to play with me and Natalie and to talk to us, but all we saw of him was him arguing on the telephone with this massive firm, being horrible to our Mum and shouting at us.

Things took a turn for the worse around about the time I turned eight, in the spring of 1990. Mum sat me and Nat down one day and told us Grandad was ill – really ill. People kept talking about the ‘C-word’ and although I didn’t really have a clue what it really meant, it was clearly bad.

Mum took me out of school to visit Grandad one afternoon at the Central Middlesex Hospital, where he was being treated. She’d popped into the baker’s on the way to collect me and she gave me a gingerbread man to eat on the train on the way there. It all started out feeling like a real treat.

But as soon as I saw Grandad in the hospital I knew something was badly wrong. I think it was the first time I’d ever seen him without his woolly cardigan on and that was enough of a shock. Instead, he was wearing a white hospital smock which seemed to smother him, he was so thin and pale. There was no pipe sticking out of his mouth any more and any Popeye strength had clearly been sapped away.

I sat on Grandad’s bed and chattered about gymnastics and Brownies and the latest dramas at Hillside Infant School while Mum squeezed into an adjoining toilet with a doctor ‘for a word in private’. It was the only place they could find to tell her that her father was dying.

When Mum walked back into the room her whole body was shaking except for her face, which was totally rigid.

The doctor had just told her the results of surgery on a blockage in Grandad’s bowel. ‘We opened him up but saw immediately there was no point in operating – it was too far gone, so we just sewed him up again. Mrs Grahame, I’m terribly sorry, but there is nothing further we can do for your father.’

Mum nearly passed out from shock but pulled herself together to come back into the room, where I was still talking Grandad through my flip routines.

We chatted for a bit longer, then Mum and I walked back to the station. When we got home she told me run out and play in the garden while it was still sunny. It was years later that she admitted to me that, while I cartwheeled up and down the lawn, she slid down our living room wall and sobbed and sobbed and sobbed.

Mum had always adored her father and it was obvious there was something special between them. I think that is why she had always understood and accepted the closeness of the bond between me and Dad.

Mum’s childhood had been pretty tough. Her family were hard-up and Grandad had a fierce temper, but no matter how violent or angry he had been, she always idolised him and never blamed him for any of the troubles between her parents.

When Grandma died of cancer when she was 51 and Mum was 18, Mum had been upset, but not devastated. But, faced with the prospect of losing Grandad, she just went into freefall – she couldn’t cope at all.

Grown-ups don’t use the word ‘terminal’ to kids and even if she had done, I don’t suppose I would have known what it meant. But I could see myself that every time we went to visit Grandad he was thinner, paler and more ill-looking. He didn’t have the energy for corny jokes any more and seemed to find it exhausting enough just breathing in and out. He was fading away in front of us.

And as Grandad slipped away, it seemed Mum was going the same way. ‘But he’s never been ill in his life and he’s not even 70,’ she would repeat again and again. She would get choked up at the slightest thing and tears were never far away.

So there we were that summer of 1990. Mum sad all the time, Dad mad all the time. Mum and Dad fighting, me and Natalie fighting. Grandad dying.

Then Rex fell ill and was taken back and forth to the vet. He was diagnosed with a tumour on his back leg and the vet said there was nothing more they could do. He’d have to be put down. Dad adored Rex, so when I saw him crying as he stroked his head one morning, I knew what it meant.

Rex was 18 and he’d been there all my life. The house felt so quiet without him. No mad mongrel racing up and down the hall every time the doorbell went. Just silence.

It was tough going back to school at the start of that new term. I’d never been academic but I’d always had fun at Hillside and been popular with the other girls. But even teachers noticed I had lost my energy and enthusiasm. Now there were so many more things to think about in my life than there had been a year ago.

And rather than just playing French skipping in the playground with all the other girls, I would spend more and more time staring at my friends, asking myself the same old questions: ‘Is my bum bigger than theirs?’, ‘Are my legs chubbier?’, ‘Is my tummy fatter?’

Nicola Carter was one of my best friends even though her bum was smaller than mine, her tummy flatter and her legs thinner. She had long, brown hair like mine and freckles scattered across her nose but oh, she was so skinny. She looked amazing.

All the kids in our class called us ‘Big Nikki’ and ‘Small Nikki’. Well, you can imagine how that made me feel. I was clearly just too big.

With so much bad stuff going on at home I threw myself into gymnastics more and more. And the more gymnastics I did, the more competitive I became about it. I may only have been seven but I was incredibly determined and driven. I only ever wanted to be the best. I knew I wasn’t as good as the other girls, not as pretty as them and not as thin as them. But rather than just think, Oh well, that’s the way it goes, I was determined to become the best, the prettiest and the skinniest.

Gymnastics had become a constant round of grades and competitions and although there wasn’t much enjoyment left in it for me, I was still desperate to excel.

One evening I was standing in the gym with the other nine girls as we waited for the results of our grade five to be read out. Finally the coach got to me. ‘Pass,’ she said. ‘Not distinction this time, Nikki. That’s a bit useless for you, isn’t it?’ She probably didn’t mean anything by it and if she did she was probably just trying to gee me up a bit, but all I heard was the word ‘useless’. It stuck in my brain like a rock and I just couldn’t shift it.

Shortly afterwards Mum was watching me line up to collect my badge at a county trials competition. She remembers that as I waited my turn she looked at my face and all she could see was torment and misery. I was only seven and I’d reached a pretty good standard as a gymnast but I felt useless.

I had to improve, I had to get better. And for that, I had to get thinner. I also deserved to be punished for not being as good as I should have been. Well, that’s what I thought. So I started denying myself treats.

Every week Mum would buy me a Milky Bar and Natalie a Galaxy to keep in our sock drawer. It was up to us when we ate them but we were both ultra-sensible and limited ourselves to one cube a day as that way they lasted longer. I’d also treat myself to a cube before training on a Saturday morning.

But when I started feeling more and more useless at gymnastics and more and more unhappy finding myself in the crossfire between Mum and Dad at home, I thought, I’m not going to have my cube of Milky Bar today. I don’t need it.

That very first time I denied myself, it felt good. Like I’d finally achieved something myself. And I liked the feeling so much that I did it again.

The other treats I had loved as a little kid were Kinder Eggs. I’d always been an early riser, which drove my parents mad, so years earlier Mum had made a deal with me that if I stayed in bed until seven o’clock I got a chocolate egg.

For ages it was just brilliant. Early in the morning I’d be wide awake but as soon as seven o’clock came round on my panda bear alarm clock, I’d go rushing into Mum and Dad’s room, climb into bed between them and claim my Kinder Egg.

But when I started wanting to be skinnier I started opening my reward, throwing away the chocolate and just keeping the toy inside.

And if anyone else, like my auntie, offered me a bag of sweets I’d just say I was full up or I didn’t like them. When I deprived myself it felt good. But even then I knew this had to remain a secret – I couldn’t tell anyone.

During that long, miserable summer the rows between Mum and Dad just grew more vicious. Mum was usually teary and weak, Dad raging or sullen. And Grandad was fading away. Everyone was pulling in different directions, caught up in their own personal tragedy.

For me, how to avoid eating became something to think about instead of what was going on at home.

By the end of the summer Grandad was really ill. One evening all four of us went to visit him. After a while Dad, Natalie and I went and sat in the corridor so that Mum and Grandad could have a bit of time alone together. We’d been sitting there about 20 minutes when she came out of his room shaking. She didn’t need to say anything. Grandad had gone. He was 69.

All the way home in the car I wailed until we got back indoors and Dad tipped me into bed exhausted.

Mum was utterly distraught and lost the plot entirely. She was 36 but felt her life was over too. It was like she was drowning but had no idea how to save herself.

‘Pull yourself together,’ Dad would shout at her when he found her crying yet again. It was his idea of tough love but Mum couldn’t pull herself together. Dad couldn’t understand why not, so they drifted even further apart.

Mum went to the doctor and said she was in a mess, she couldn’t cope any more with her grief, Dad’s anger and their fighting. The doctor said she would talk to Dad about things if he’d make an appointment to see her.

‘Please go to the GP, Dave,’ Mum begged one evening as she washed the dishes. ‘You need support for all the stress at work otherwise we’re not going to survive this. I haven’t got any energy left to fight you any more. We need proper help.’

But Dad just refused. ‘I’m not going,’ he said. And I think at that moment, with Mum leaning against the kitchen sink and Dad standing in the conservatory, my parents’ marriage ended.

A couple of days later – about a fortnight after Grandad died – Mum woke up and thought, Right, this is it. Life really is too short for all the rowing and fighting. I want a divorce. Just like that, after 15 years of marriage, she decided she’d had enough. Natalie and I would have had to be blind, deaf and very stupid not to realise that this time things were really bad. But, because divorce is such a big thing for a kid to get their head around, I don’t think either of us had really thought it would happen.

One morning, soon after Natalie had left for her school and I was waiting for Mum to walk me to mine, she came into my room, knelt down in front of me and just hugged me and burst into tears. I said, ‘Mum, why are you crying?’ And she just wouldn’t tell me. I kept asking her why, but she couldn’t say.

It was a Saturday morning a couple of weeks later when Dad and Mum told us what was really happening. They had been rowing for hours, shouting and screaming at each other. Nat and I just wanted them to hurry up because Dad always took us swimming on a Saturday morning.

Then they came out of the kitchen and took us into the living room. ‘Right,’ said Mum, ‘Your dad and I are going to separate.’

I felt numb. Mum was crying, then Dad started sobbing like a baby. Every time she went to speak, he would shout over her. Then Mum was screaming, ‘Let me speak, let me speak,’ but when she began he stormed out of the room. It was like something out of EastEnders – I didn’t think this could happen in real life.

My whole childhood had been blown apart.

Half an hour later, Dad took me and Natalie swimming and we had a really cool competition to see who could stay underwater the longest. Weird, isn’t it?