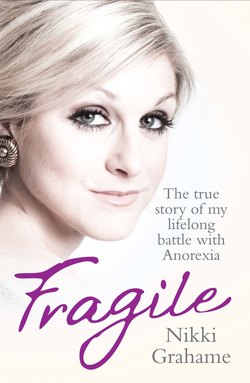

Читать книгу Fragile - The true story of my lifelong battle with anorexia - Nikki Grahame - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A BIG, FAT LUMP

ОглавлениеI pulled my Benetton stripy top over my head and slid my jeans with the Minnie Mouse patches down over my ankles, then just stood and stared.

I was standing, again, in front of the floor-length mirror inside the door of the wardrobe in Mum and Dad’s bedroom, wearing just my knickers. In reality I was probably a tiny bit chubby at the time, but all I could see was someone mega fat compared with everyone else at gymnastics and everyone else in my class at school, if not the rest of the world.

By now I was spending more and more time analysing my body and staring at the bodies of other girls around me to see how I compared. At that time cycling shorts were really in fashion and everyone was wearing them. I’d look at anyone wearing them and if their thighs touched when their feet were together they were fat. If their thighs didn’t touch they were skinny and I wanted to look like them. Mine touched.

School swimming lessons were a total nightmare – all those girls in their swimming costumes looking slim and gorgeous and athletic, and then there was me. I was just a big lump. I felt fat compared with all my friends and virtually everyone else.

I spent ages working out which girls in my class had bigger thighs than me, which had rounder tummies and which had chubbier arms.

And just when I thought I couldn’t look any worse plodding from the changing rooms to the swimming pool, the unthinkable happened – Nicola Carter got a green swimming costume with ruffles on it. Exactly the same as mine! Now it would be obvious to everyone that my bum was totally massive next to hers. I’d never ever live down the ‘Big Nikki’ label.

I hated the way I looked. Giving up chocolate had made me feel good but it hadn’t really done anything to make me lose weight, so I had to take more drastic action. At eight years old I was too young to understand about calories, but I knew – like all kids do – that some things are ‘bad’ for you. For goodness sake, adults never stop going on about it: ‘Don’t eat all those crisps, they’re bad for you’ or ‘Eat your cabbage, it’s good for you.’

So really it was quite easy to know what to do – just follow the grown-ups’ rules. I started denying myself all the ‘bad’ things that Mum, Dad, my friends’ parents and teachers had ever talked about – chips, pastry, custard, puddings, chocolate and crisps. If Mum was going to cook ‘bad’ foods I’d suggest something else instead, saying I’d gone off chips or wasn’t in the mood for custard. And at first, preoccupied with her own losses and sadness, Mum didn’t have a clue what I was up to.

I took any opportunity I could find to deprive myself of ‘bad foods’. One Saturday afternoon it was Joanna Price’s birthday party. Her parents had arranged for a swimming party but while everyone else was chucking each other in the pool and screaming crazily, I stood quietly at the shallow end, checking out their thighs and tummies. Afterwards, back at Joanna’s house, I carefully picked all the fruit out of a trifle, leaving the jelly and custard at the bottom of my bowl. I was determined I would be the skinniest girl in a swimming costume for the next party.

Then I started giving away my food at lunchtime. Every morning Mum would send me off to school with my yellow teddy-bear lunchbox filled with sandwiches, a bag of Hula Hoops, a Blue Riband chocolate bar and a satsuma. And every night I returned with the box empty except for a few crumbs stuck to the bottom.

What Mum didn’t know was that I’d hardly touched the food she had put inside. It was easy to offload the crisps and chocolate to any of the greedy-guts who sat near me at dinner break. After a couple of months I started depriving myself of the sandwiches too. They were more difficult to give away, so I’d stick them straight in a bin instead.

With a couple of hundred kids all sitting eating their lunch in the school hall, there was no way a teacher could notice what I was doing. One day my friend Joanna asked why I kept giving my food away but I just laughed and changed the subject. I didn’t really have an answer for that question myself.

As I never, ever felt hungry, I didn’t care about going without lunch. I just felt good inside when I denied myself. I felt kind of victorious, as if I had won a battle that only I was aware was taking place.

By the autumn of 1990 my thinking had moved determinedly into a place where I was going to eat as little as possible and become as skinny as possible. Then I started skipping breakfast. Before, Mum had always made me and Natalie sit down for a bowl of Frosties or Ricicles. But it was so frantic in our house in the morning that it was dead easy to chuck them in the bin or ram them down the plug hole of the sink without Mum or even Natalie noticing.

Mum would be dashing in and out of the shower to get dressed and make her own breakfast and I quickly learned how to get rid of any evidence very fast indeed. Other mornings I’d say to her, ‘Don’t bother sorting any breakfast for me. I’ve already made myself a couple of slices of toast.’ Even then I was like a master criminal – I’d crumble a few crumbs of bread on a plate, then leave it on the draining board to make my story appear believable.

At first Mum bought it, but then she noticed I was losing weight and her suspicions were aroused. One afternoon I walked in from school and instead of her normal cheery smile and ‘Hi, darling,’ she just stared at me. I could see the shock in her eyes. She had noticed for the first time that I had dramatically lost weight. My grey pleated school skirt was swinging around my hips whereas before it had sat comfortably around my tummy. And my red cardigan was baggy and billowing over the sharp angles of my shoulders.

‘Nikki, you’re wasting away,’ she half joked. ‘You’ll have to eat more for your dinner.’ But behind the nervous laugh there was strain in her voice. Maybe in the back of her mind she had noticed I’d been getting skinnier for a while, but now it was blatantly obvious.

It didn’t bother me how worried she was, though. I was losing weight and it was good, good, good.

From then on Mum watched me like a hawk at every meal. The next breakfast time I used my ‘I’ve had toast earlier, Mum’ line she was on to me in a flash.

‘Well, if you have, young lady, how come the burglar alarm didn’t go off when you went into the kitchen, because I set it last night?’ she said.

She angrily tipped a load of Frosties into a bowl, doused them in milk and slapped them down in front of me. I spent the next 20 minutes pushing them around the bowl with my spoon until she nipped into the hall to find Natalie’s school shoes or something and then I leapt out of my chair and shoved them down the sink. Ha, ha, I’d won after all!

Dinner times got a lot harder too. For a long while I had been eating the meals Mum made me at night – I’d allowed myself that much, but no more. But that autumn, as the days grew shorter and the weather colder, I just got stricter and stricter on myself until there were only certain bits of dinner I would allow myself to eat.

Why was I doing it? I had started out just wanting to be thinner and a better gymnast but quite quickly my eight-year-old mind had come to see not eating as something I had to do. It was like a compulsion. I had to eat less and be in total control of what I was eating. And if Mum tried to stop me I had to find a way to get away with it.

By now, depriving myself was just as important as, if not more than, becoming skinny.

Dinner times became a battleground. As soon as the front door slammed shut behind me as I walked in from school there would be the usual yell, ‘What’s for dinner, Mum?’, that is heard in millions of homes across the country every afternoon. But while most mothers’ replies are normally greeted with a ‘Yeah, yummy’ or at worst a ‘Yuk, that’s gross,’ in our house Mum’s evening menu was just the beginning of a negotiating session that could last for hours.

Usually Mum gave in and made me whatever I demanded because she was desperate for me to eat something and she thought that if she gave in to me, at least I would have something. But even that didn’t always work. Often she would slave for ages cooking something that she thought I might find acceptable, chicken or fish, only for me to shove it away the moment she laid it down on the table.

Mum tried everything to make me eat. She tried persuading me: ‘Go on, Nikki, just for me, please eat your dinner up.’ And she tried disciplining me, threatening that I wouldn’t be allowed to go out with my friends or to gymnastics unless I ate.

Sometimes she got so frustrated with me that she totally lost it and started screaming and shouting. But that was fine. I’d just scream and shout back.

Other times she simply sobbed and sobbed, begging me to eat while I looked at her blankly. Getting Mum crying was always a result. It meant she hadn’t the strength to fight that particular mealtime and it was a victory for me. Dad was still living in the house but he was normally at work at mealtimes, which meant Mum was desperately trying to cope with me on her own – as well as watching her marriage collapse and trying to come to terms with having lost Grandad.

Although only eight, I was already an accomplished liar. ‘Did you eat your lunch at school today, Nikki?’ Mum would ask. ‘Yes thanks. The egg sandwiches were great,’ I’d say. I always gave just enough detail that Mum couldn’t be entirely sure whether I was lying, although deep down she must have thought I probably was.

I’d also discovered a brilliant new way of getting thin – exercise. I started with sit-ups every single night in my bedroom. It was great because Natalie now slept in the attic room, which meant I could get up to anything in my room and no one would know.

‘Night, darling,’ Mum would say, tucking me into bed and kissing my forehead. ‘Night, Mum,’ I’d call out to her as she shut the door, already throwing back the duvet, ready for at least 200 sit-ups before allowing myself to sleep.

Soon the bones started to jut out at my elbows and my legs looked like sticks. Mum was becoming more and more worried. She was equally concerned by what she saw in my face – a haunted, troubled look and eyes that had lost every bit of sparkle. My sense of fun had disappeared and I was withdrawn, distracted and sullen.

One Sunday lunchtime all four of us went to the Beefeater for a roast. It was a birthday ‘do’ and so we were all making a show of togetherness.

When we got to the table, Mum, Dad and Nat all sat down while I hovered at the edge. ‘Sit down, Nikki,’ said Mum. But I couldn’t. I had to keep moving, had to keep using up that energy inside me to make me thinner. And I didn’t want to be near all that food – it felt disgusting.

I refused to sit down for the entire meal. Mum and Dad both tried to persuade me and got mad with me, but nothing could make me sit at that table. That was when they really started to worry there was a major problem emerging. And they were scared.

It was about this time that The Karen Carpenter Story was on television. It was on too late at night for me but Mum saw it and immediately spotted the similarities. And it was then that the presence of ‘anorexia’ as an illness first entered our lives.

Anorexia – the name given to a condition where people, usually women, starve themselves to reduce their weight – has probably been around since the end of the 19th century. In Victorian times it was thought to be a form of ‘hysteria’ affecting middle- or upper-class women. It was only in the 1980s in America that it became more recognised and clinics began treating sufferers.

The death of Karen Carpenter, one half of the brother-and-sister singing duo The Carpenters, played a huge part in increasing understanding of the illness. She had refused food for years and used laxatives to control her weight before dying in 1983 from heart failure caused by her anorexia.

It was only after the film of her life, made in 1989, was aired in Britain that people here had any idea about what anorexia really was. And even then it was regarded as a condition which only affected teenage girls. That’s what made Mum think at first that it couldn’t be what was wrong with me. I was only eight, so how could I possibly have it? But still she was worried.

‘Right, if you won’t eat your dinner, I’m taking you to the doctor – tomorrow!’ she shouted at me at the end of another fraught meal.

The following evening after school – it was towards the end of 1990 – Mum marched me into our local surgery in Northwood. Our family GP was off on maternity leave, so we saw a locum instead. Mum explained to him how I would agree to eat only certain things and how at other times I’d refuse to eat entirely or shove food in the bin or down the sink when I thought no one was watching.

The doctor was one of those types who treat children as if they’re all a bit thick. ‘So, my dear,’ he said slowly, ‘what have you eaten today?’

This was going to be a breeze, I just knew it.

‘Well,’ I said quietly and hesitantly, my very best ‘butter wouldn’t melt’ look on my face. ‘I had a slice of toast for breakfast, then my packed lunch at school, although I didn’t have the crisps because they’re not very good for you, are they?’

Mum looked at me in disbelief. ‘Tell the truth, Nikki,’ she hissed.

‘But I am, Mum,’ I lied effortlessly, thinking of the one mouthful of sandwich that had passed my lips all day.

‘Well, Mrs Grahame,’ said the doctor. ‘I can see she’s a bit on the skinny side but I don’t think it’s anything to worry about at this time. It’ll all blow over, no doubt. You know what girls are like with their fads and fashions.’

‘She’s not faddy,’ insisted Mum. ‘I know my daughter and it’s more serious than that.’

‘Well, let’s just keep an eye on her and see what happens,’ said the doctor, his decision clearly made.

We drove home in silence, Mum feeling defeated again and me victorious once more. No way was anyone going to be ‘keeping an eye’ on me!

And when I wasn’t doing the screaming and shouting it was Mum or Dad’s turn. After their initial decision to split they had decided to give their marriage another go. Then the rows just became even more vicious and after a torturous couple of months they returned to the idea of divorce. But because they couldn’t agree on what to do about selling the house and splitting the money, we all carried on living under the same roof.

In my eyes Dad was still acting like a monster. He’d gone from someone I would chase down the road every time he left the house to someone so bitter and angry that I didn’t want to be around him. I transferred all the intensity of my feelings for Dad straight over to Mum. And now I’d lost Grandad and Dad, I clung to her, both emotionally and physically. I reverted to acting like a toddler. If we were watching television I’d insist on sitting on her lap and if she went out I’d stand by the window waiting for her to return. If it was evening time I’d lie on her bed until she got home.

Mum became the focus of everything for me – both my intense love on the good days and my anger and frustration on the bad.

By worshipping Dad rather than Mum I’d probably backed the wrong horse, but I wasn’t going to lose out now. No, that would have to be Nat. That caused big rows between me and her then – and it still does even today.

But even though Natalie and I both desperately needed Mum, she didn’t really have much left to give us. She was weak, crying all the time, and I was just so needy that she felt exhausted, which in turn made me feel abandoned.

My world was falling apart.

When Mum couldn’t stand sharing her bed with Dad any more she decided that she, Natalie and I would all move up into the attic and live there. From now on I slept on a double bed with Mum as I couldn’t bear to be physically apart from her. Natalie slept on an old brown sofa. All our toys were still scattered around the room, so it seemed like a bit of adventure having Mum up there with us, but it was kind of weird too.

By now I was struggling at school. The less I ate, the harder I found it to concentrate. And so much of my energy was being spent thinking about how I was going to dodge the next meal, how much I’d eaten so far that day and what Mum might be thinking about making for dinner that night, that I just couldn’t focus on lessons at all.

Then at break times I started going to the girls’ toilets and doing sit-ups. I would do dozens in a session before the bell, then dash back to my desk all hot and sweaty. One of the girls in my class must have told on me because one day a teacher came in and found me and said I wasn’t allowed to do it any more.

That must have been when school started getting really worried about me and called Mum in for a meeting. They said they were concerned about my rapidly falling weight and that I didn’t seem able to concentrate in class any more.

Mum hauled me back to the doctor again. It was a different locum, so we went through the same charade of my pretending to be eating a healthy if meagre diet and the doctor believing me. Again we were sent home, Mum even more dejected and me even more triumphant.

Dad was seldom around at mealtimes despite still living in the house, so he rarely saw the battles. When Mum tried to talk to him about me, it just ended up in another row as they tried to blame each other for my getting into such a state. Although what kind of state it was exactly, they still weren’t sure themselves.

One night Dad was in the pub when my friend Sian’s mum walked up to him.

‘Are you Nikki’s dad?’ she asked. Dad nodded and this woman he’d never met before grabbed his arm with a terrible sense of urgency.

‘My daughter is really worried about Nikki,’ she said. ‘She’s hiding in the toilets at school doing exercises and refusing to eat. Are you aware of what’s going on?’ she said.

Dad looked blank and was forced to admit he didn’t really know the extent of what was happening at all.

‘Well, you need to be worried,’ my friend’s mum told him. ‘If you don’t do something, your daughter is going to die.’