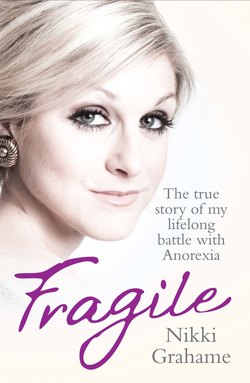

Читать книгу Fragile - The true story of my lifelong battle with anorexia - Nikki Grahame - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

FUN, FOOD AND FAMILY

Looking back to the house at 37 Stanley Road before everything went wrong, it always seems to have been summer. Back then everything was good, better than good. I had one of those childhoods you normally only see in cereal adverts.

We didn’t have bags of money or live in a huge mansion, but we had fun. There were summer holidays to Greece, Mum and Dad would cuddle up on the sofa to watch a video on a Saturday night, I had a grandad I adored who had an endless supply of corny jokes, and sometimes my older sister/occasional friend/usually arch enemy Natalie even let me play with her collection of scented erasers!

There was Mum and Dad and Natalie and me (and Rex, our dog). And it worked. My mum, Sue, was tall and slim. She was shy compared with other kids’ mums but she doted on me and Nat. She worked as a dinner lady but was always home in time to cook our tea – and she was an amazing cook. Nothing fancy, but proper home cooking that we all sat around the table to eat. Every night it was something different – spaghetti Bolognese, lasagne or a macaroni cheese that was worth running the full length of Stanley Road for.

Then there was my dad, Dave. And while of course I loved Mum, with Dad it was something more – I adored him.

Mum always laughs that the love affair between me – Nicola Rachel-Beth – and Dad started within minutes of my arrival at Northwood Park Hospital on 28 April 1982. After Natalie, Dad had been hoping for a boy but when I burst into the world screaming my lungs out he was, for some reason, totally smitten. From that point onwards I was the apple of his eye.

After the birth, the nurses wheeled Mum away to stitch her up. She left Dad sitting in a corner of the room by a window, holding this little bundle with jet-black, sticky-up hair and chubby cheeks.

When Mum was brought back an hour later, the sun had gone down and the room was pitch-black but Dad hadn’t even got up to switch the light on. He was still sitting in exactly the same position, transfixed by the new arrival – me.

As I got older the bond only grew stronger. But it was kind of OK because there was an unspoken agreement in our house – Mum had Natalie and Dad had me.

I couldn’t leave Dad alone. And for him little ‘Nikmala’ was pure delight.

By the time I was four or five, every time Dad left the house to go to work or pop down the pub I’d go belting down the road after him, begging to be allowed to stay with him.

I’d spend hours standing outside the betting shop at the corner of our street after Dad disappeared inside, rolled-up racing pages clenched in his hand as if armed ready for battle. Kids weren’t allowed in and the windows were all covered over, but whenever the door was pushed ajar I’d sneak a glimpse of that mysterious male world of jittery TV screens, unfathomable numbers and solitary gamblers, all engulfed in thick cigarette smoke.

It became a standing joke in our family that whenever Dad emerged from the bookies’ with a brisk, ‘Right, off home now, Nikmala,’ I’d reply, ‘Can’t you take me to another betting shop, Dad? Please?’

By the age of five I’d started going running with Dad. He loved keeping fit and so did I.

Dad worked shifts at a big bank in London, looking after its computer system. It meant he wasn’t around a lot of the time but the moment he stepped inside the door I was all over him.

Everyone wanted to be around Dad, to laugh at his jokes and hear his stories. Well, at the time I thought it was everyone, but looking back I think it was probably just women. In fact even at seven I knew that Dad was a bit of a ladies’ man. He couldn’t take us for a plate of chips at the Wimpy without chatting up the girl behind the counter.

You name her, Dad would try to turn on the charm for her – my nursery school teacher, the lifeguards when he took me swimming on a Sunday morning, holiday reps; pretty much anyone really. But at that point it just seemed harmless, a bit of a fun. I had no idea what was really going on in my parents’ marriage and how it would soon tear our family apart.

We also spent a lot of time with my Grandad, my mum’s dad. He always had a pipe sticking out of the corner of his mouth and Natalie and I called him ‘Popeye’. He had just one tooth in his bottom gum which he’d wiggle at me, ignoring my squeals, as I sat on his lap, cosy in the folds of his woolly cardigan.

Up until I was seven everything was fun. With just two years separating us, Natalie and I were constant playmates. Then, as now, our relationship veered between soul mates one day and sworn enemies the next, but hey, at least things were never boring.

We were always very competitive with each other. Natalie was a jealous toddler the day I first appeared home from hospital in the back of the family Morris Minor. And we still fight over Mum’s attention now. Mum always went out of her way to treat us fairly and make sure we both felt included in everything. But it was never enough to stop the bickering. If I even thought about touching one of Natalie’s favourite Barbie dolls, she’d go mad. But I was just as protective over my toys.

When I was five or six I would pore over the family photo albums and jealously interrogate Mum about any pictures I didn’t appear in.

‘Why are you cuddling Natalie in this picture and I’m not there?’ I’d demand. ‘You weren’t born then, Nikki,’ Mum would explain.

In another picture from that old album Dad is pushing me in the buggy while Mum holds Nat’s hand. ‘But why weren’t you pushing me that day, Mum?’ I said. Even though I had Dad’s total devotion, I wanted Mum’s too. And if that meant trampling all over Natalie to get it, so be it.

My competitive nature and quick temper had probably been bubbling under since birth. I cried pretty much continuously for the first fortnight after I was born, which should have given Mum a bit of a clue what she was in for.

And as a toddler I was pretty tough. Certainly any three-year-old who ever went for a spin in my favourite bubble car at the Early Learning Centre in Watford never made that mistake twice. Mum found me pulling one kid out of the car by his jumper before leaping in and driving off round the shop myself.

At play school I had to stand in the toilet on my own one morning for putting a wooden brick on one of the other kids’ heads. Another time I was hauled up for kicking one of the boys.

At infant and then junior school I was always up to something, getting into scrapes. Dad called me his ‘little bruiser’ but I knew he was proud of me for sticking up for myself. But I was popular in class too – I had a big group of friends and I was always the leader.

I was in the Brownies, went to the church’s holiday club, loved swimming at weekends and was always out playing on my bike after school with kids from our street. My friends Zanep and Julidah from down the road were always round our house and we’d play for hours in the twin room I shared with Natalie.

Our house was a fairly typical chalet bungalow in the north-western suburbs of London, with two bedrooms overlooking the street at the front and above these a big attic which we used as a playroom. Our garden was magical. Back then it seemed huge to me, with its long slope of grass stretching from a wooden-boarded summerhouse all the way down to the living room window. To one side of the garden was a ‘secret’ passageway which got narrower and narrower until it reached the special spot Natalie and I used for burying treasure – well, Mum’s old jewellery from the 1970s. In another corner there were swings, a slide and a climbing tree.

On the patio at the top of the garden, we would help Dad light bonfires in the winter and in summer we would stage our theatrical productions there, prancing and dancing up and down.

Sometimes I think that house in Stanley Road will haunt me for the rest of my life – I was so happy there and I was a kid there. Because what I didn’t know then was that the time spent living in that house up until I was seven was my childhood – all of it.

The only thing that made it OK to be called inside from that magical garden was the thought of one of Mum’s dinners. Up until the age of seven I would eat pretty much anything she put in front of me. I was never one of those ‘just three chips and half an organic sausage’ type of kids.

I’d fed well as a baby and as soon as I went on to solids, anything Mum served up, I’d eat. On Sunday it would be a big roast and then midweek we would have home-made burgers, meatballs or liver and veg. And that would be followed by a proper dessert – a steamed pudding or fruit with custard. I loved Mum’s food. We all did.

And going out to restaurants was a real treat too. I was only two when we all went on holiday to Crete and I ordered a huge plate of mussels in a restaurant. ‘You might not like those, Nikki darling,’ Mum warned, but I wasn’t going to be dissuaded.

When my meal arrived everyone in the restaurant was staring at this tiny little toddler tucking into a huge plate of shellfish – but I loved it.

Back then food was fun and a big part of our family life. But within a few short years there was no fun left in either food or our family.