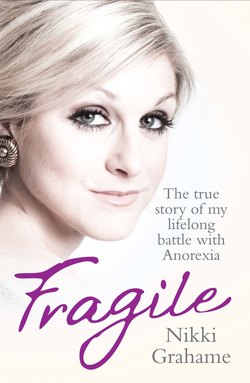

Читать книгу Fragile - The true story of my lifelong battle with anorexia - Nikki Grahame - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE MAUDSLEY

ОглавлениеI was lying on the sofa wearing a billowing white dress dotted with huge purple lavender flowers when the call came saying they had found a specialist unit for me.

That morning I’d crawled up to the attic and dug the dress out of our big red dressing-up box. I had a porcelain doll that had an almost identical dress and I decided I wanted to look like her. It must be easy being a doll, I thought.

I put the dress over my head, then, exhausted by the effort, returned to the sofa, where I lay and watched Mum vacuuming around me. By this point I was so sick I could barely move.

‘We’ve got a place for your daughter at the Maudsley Hospital in south-east London,’ the official-sounding woman on the phone told Mum. ‘Can you come straight away?’

‘Oh yes,’ Mum replied. ‘I’d go to hell and back to save my daughter.’ She didn’t know then that hell and back was precisely the journey she would be making over the next nine years.

The following few hours were a flurry of activity. Mum rang Dad, who came straight home from work, picking up Natalie from school on his way. We drove to the station, then set off on the tube journey to the Maudsley.

The Maudsley Hospital is the biggest mental health hospital in Britain. It treats people with all sorts of horrific mental problems, including kids with emotional and behavioural problems, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress, depression and other serious psychiatric conditions. When we turned up there that day, 5 March 1991, I had no idea I was being bracketed with kids so seriously ill.

The journey from Northwood Hills tube station to the other side of London was exhausting. When Mum helped me off the train at Elephant & Castle, people were staring at me. I must have looked like a kid dying of cancer. And when I saw the stairs leading up out of the station, I thought I couldn’t do it – I just didn’t have the energy to get up there. But somehow Mum and Dad helped me and we clambered up into the daylight and through the dirty doors of a red London bus. After about ten minutes the bus lurched to a stop and the doors flew open again. In front of us was the Maudsley.

It was certainly a serious-looking building, with two grand pillars flanking a flight of stone steps that led up to the main entrance. I felt tiny as I crept up the steps and entered the monstrous great building.

Inside we were greeted by a smiley nurse who showed Mum and Dad into a side room for a meeting with Dr Stephen Wolkind, the hospital’s expert in child psychiatry. Natalie and I were taken into another room by a nurse – let’s call her Mary – who gave us crayons and paper to keep us occupied. It felt like Mum and Dad were gone for hours. After Natalie and I had coloured and drawn everything we could think of we wandered outside and sat on the low bars of a climbing frame in the fading spring sunshine.

‘I wish Mum and Dad would hurry up so we can just clear out of this place and go home,’ I said to Natalie. It had never occurred to me I wouldn’t be back in time for Neighbours.

Then Natalie pushed me on the swings for a bit. I was too weak to push her. But still Mum and Dad didn’t emerge from their meeting. What could they be talking about?

Finally Mary, the nurse, came out to the swings and told me it was time to go in. She led me down a corridor and into a small cubicle. Inside there was a narrow single bed, a table and a chair. She sat me down at the table and told me to wait a moment. A couple of minutes later she returned carrying a glass of milk, a couple of cream crackers and some cheese.

‘Here’s a snack,’ she said, placing it in front of me, then sitting down herself on the edge of the bed.

I looked at the plate, barely able to hide my disgust at the big chunk of cheese plonked in the middle. Didn’t these people know cheese was about the most ‘bad’ food around?

‘Oh no, I don’t fancy that at the moment, thank you,’ I said quietly.

‘Nikki, you have to eat your snack,’ replied Mary. ‘I’ll talk to you when you have finished it.’

For more than an hour we sat in silence. A few times I tried to engage Mary’s eyes, buried deep in her pudgy face, but each time she looked away. It was only later I discovered that it was the Maudsley’s policy to avoid any interaction with eating-disorders patients during mealtimes. So instead I silently gazed out of the window watching aeroplanes etching white lines across the sky of south London.

Finally, another nurse came into the room.

‘Right, Nikki,’ she said brusquely. ‘Your mum and dad are going home now, so you’d better say goodbye to them.’

Mum was standing in the doorway behind the nurse, her gaze flickering between me and the floor. I could tell by the red puffiness around her eyes that she had been crying. Even Dad looked shell-shocked.

At first I couldn’t quite understand what was happening. I’d always thought we were just here for a meeting with specialists. It hadn’t occurred to me for a moment that they might want to keep me here. But the look on Mum and Dad’s faces told me in a second that this was exactly what was happening.

‘No, no. Don’t take my mum away,’ I pleaded, my voice high-pitched but starting to choke with the realisation of what was happening.

‘I need my mum. Please don’t make her go. I need her.’

As Mum and Dad moved towards me to kiss me goodbye, I started to wail. This just could not be happening. Mum couldn’t be abandoning me. Not her, surely? OK, Grandad and Dad had left me, but Mum wouldn’t do that. Would she?

My screams grew louder and louder, like the howling of a wounded animal. I watched the nurse gently take hold of Mum’s elbow and lead her back out into the corridor. ‘No, no, noooooo,’ I screamed.

I lunged forward and flung my bony arms around Mum’s thighs, my screams now subsiding into loud sobs as I begged her not to leave me in this strange place surrounded by strange people.

Tears were sliding slowly down Mum’s face as she tried to untangle my arms from her legs and steady herself.

‘I’ve got to, Nikki,’ Mum kept saying. ‘I’ve got to – the doctors are going to make you better. You’ll be home soon, I promise.’

But I didn’t hear any of that. My head was thumping and my ears were filled with a strange howling – I didn’t realise then that it was me making such a horrific noise.

Mary and the other nurse peeled me away from Mum but I started screaming and lashing out at them. I was so angry, so furious that everyone would gang up and do this to me. Why me? After everything else, why me?

I flung myself around the room, banging into the bed and table, flailing my arms and legs.

Eventually, Mary pinned me to the floor to stop me smashing my head while the other nurse gently pushed Mum and Dad into the corridor.

For a moment I stopped struggling and took a breath. Through the glass window of the door I could see Mum looking back at me over her shoulder as she walked away. She had walked away and left me sobbing on the floor. Mum, who’d been there me for every second of every day, who carried me like a baby from room to room, who cuddled me to sleep and kissed my tears. She had left me.

I lay totally still and heard the lock on the door at the end of the corridor click shut. I was eight years old and totally alone. I cried until my head pounded and I was shaking with exhaustion.

After five minutes Mary picked me up from the floor and eased me back into the chair by the table.

The two cream crackers and lump of cheese were still sat there on the plate. My whole life had been upended once again but that chunk of cheese wasn’t going anywhere.

‘Now, Nikki,’ she said, ‘we’re going to work you out an eating programme which is going to make you better.’

She was fat and spoke with a strict, headmistressy voice that I could tell meant she wouldn’t put up with any negotiation. I was so scared.

‘If you stick to the programme and eat your food you will see your Mum in a couple of weeks,’ she told me. ‘As for now, eat your snack up and then we’ll talk to you.’

‘When am I going to see my mum?’ I mumbled through my tears.

‘Eat your snack and then we will talk to you.’

‘But I need her. I need her.’

‘Eat your snack and then we will talk to you.’

‘Please let me see her. Please.’

‘Eat your snack and then we will talk to you.’

And that is how it went on. Me, sobbing, begging and way beyond being able to think about eating. Them, refusing to talk to me, comfort me or even look at me unless I started eating.

At six o’clock they took away the plate of crackers and cheese and replaced it with a meat casse role dish with mash and peas. Again I looked at it and refused to eat. Again they sat near me at the table, refusing to speak unless I ate.

‘Please, when can I go home?’

‘Eat your dinner.’

At eight o’clock they took the cold, congealed food away and brought a glass of milk and a small KitKat.

‘When am I going to see my mum?’

‘Eat your snack.’

At 8.30 the chocolate and milk were taken away and the nurse said it was bedtime. I looked over to the bed where the pyjamas Mum had sneaked into her handbag on the way here had been laid out for me.

The only time I’d ever been away from home before was at a Brownie camp and then I was so miserable I’d wet the bed. How on earth was I going to manage in this place with absolutely no one I knew around me and no idea when I might be going home?

I was shaking as I swung my legs in between the plain white sheets. I thought of my teddy-bear duvet cover. I thought of my sticker collection. I thought of Mum and Dad and Natalie all doing just what they had done last night, last month, last year – but without me.

How could this be happening?

One of the nurses sat on the bed as I lay there and closed my eyes. It can only have been exhaustion from that long day that made me able to sleep.

Next morning it all began again. I was woken by a nurse and got up and dressed myself. At eight o’clock a tray was put on my table with a bowl of cornflakes, a slice of bread and butter and a glass of orange juice on it. I allowed myself the orange juice and left everything else.

Then they set about weighing and measuring me. My weight had dropped to 18 kilos (2 stone 12 lb) – the average weight for a four-year-old. And I was a month off my ninth birthday.

The doctor’s reports from that assessment say I was ‘finding reality of life too hard to bear and wished to be dead to be reunited with her idealised grandfather’. I was the worst anorexic case they had ever treated at the Maudsley and there was a real concern that unless the weight went back on immediately, I could die.

‘You are dangerously underweight,’ Mary, my key nurse, told me. ‘You will not be allowed to see your Mum until you eat. And you will not be allowed to speak to your Mum until you eat. And if you still refuse to eat we’re going to take you to a medical ward, put a tube into you and force-feed you.’

No one ever asked me if I wanted to put the weight back on. No one ever considered I might not want to get better.

But I realised then that this woman was totally serious and this wasn’t a battle I was going to win.

And, young as I was, I was old enough to know that my only option was to play the system.

OK, I’ll comply with their rules, I thought. But as soon as I get out of here I’ll eat whatever I want and get as skinny as I can as soon as I can. I’ll eat whatever they serve me up and pretend I’m better.

The food’s just like medicine, I told myself. I’ll take it to get them off my back. So every mealtime I sat obediently at the small, square table, pushed up against a blank wall, and slowly yet surely cleared my plate.

It was real old-fashioned school food, like liver with potatoes and green beans, steak and kidney pie and shepherd’s pie. All of it was disgusting but I got my head down and got on with it.

During mealtimes there was no one to talk to, nothing to look at and nothing to do. In some ways eating the food relieved the boredom – and knowing this was just a game, something I’d do to shut everyone up, made me feel like I was still in control too.

And when I ate my food everyone treated me so much more nicely. If I ate my meals I’d be allowed out of my cubicle to play with the other kids on the ward. There were about ten of them, but I was the only one with an eating disorder. The rest were just oddballs.

A girl called Janey used to run up and down the ward shouting and swearing at the nurses. She’d been kicked out of school and seemed totally out of control.

Then there was Anna, who was about the same age as me, and she had behavioural problems and Down’s Syndrome. At that stage I was really into Felt by Numbers, a cross between Fuzzy Felt and Painting by Numbers. I was mad about it and for a while Mum had been buying me a box of it every weekend. When I’d finished my felt works of art I Blu-Tacked them up all around my room and they looked amazing.

One morning Anna came into my room when I wasn’t there and pulled every single one of my Felt by Numbers off the wall and threw them on the floor. When I returned and saw hundreds of pieces of felt lying higgledy-piggledy all over the floor I was heartbroken. I squatted down, picked them up and stuck each tiny piece back in its correct place. It took hours.

Next morning Anna came back and did exactly the same again.

The boys on the unit were really naughty too – some had behavioural problems and others would shout and swear at any time of the day or night. And we had another couple of Down’s Syndrome kids too.

I’d never come across kids with mental problems before and it was utterly terrifying. The screaming and shouting at night, the dramatic mood swings and violent outbursts were all alien to me and I felt so isolated. If one of the kids was having a temper tantrum at night, I’d pull the sheets and blanket over my head and try to block out the noise by thinking about home.

But the other kids’ rages and fits taught me something too – it got them attention and for a short while it gave them control. I think that on some level this sunk into my brain because within the year I was ranting and raving like the rest of them.

My first week at the Maudsley seemed to last for ever but within a month I understood the system and just got on with it. As a child you become institutionalised very quickly.

I made friends with a couple of the other girls and even the really weird kids started to seem more normal with every day that passed. There was a girl called Emily who used to shout all the time and couldn’t stop lying. She probably had Tourette’s Syndrome or something similar, but at the time I thought she was just mental. Even so, we became friends and would hang around together. Well, it was either that or being on my own all the time.

I’d been in the Maudsley for a fortnight before Mum and Dad were finally allowed to visit. When it was time for them to leave I cried hysterically again, grabbing hold of Mum’s leg. After that they came every week and I got more used to the partings, but it was never easy. Mum was relieved that I had a bit more meat on me and that for the moment I was safe, but they didn’t dare look any further forward than that.

Natalie came to visit a couple of times but only because she was ordered to by Mum. I could tell from the way she looked around the place out the corner of her eyes that she hated it. I don’t blame her at all. She was still just a kid herself and it was a dark, horrible, looming building filled with all these nutcase kids.

I think she also felt sorry for me having to live there. As my big sister, she felt bad I was there and not her, but at the same time she couldn’t help feeling glad it wasn’t her too.

Spending all weekend on the ward was really miserable. All the other kids went home on a Friday evening so I’d be on my own apart from a couple of nurses who were called in especially to look after me.

Chesney Hawkes’s ‘The One and Only’ was number one in the charts at the time and whenever I hear that song I’m instantly transported back to the Maudsley with that playing on radio and me playing the hundredth game of KerPlunk with a nurse in a deserted day room on a Saturday afternoon.

Those weekends dragged on for ever. Sometimes one of the nurses would take me out on a little trip but other times I’d just watch films or write letters to my friends.

Then, after three months, I was told that as long as I continued to reach my target weight each week I would be allowed to go home at weekends. I was over the moon.

I was weighed every Friday afternoon and if I hit my target, Mum and Dad could come and collect me. If I didn’t hit the target, though, there was no way on earth I could persuade the doctors to let me go.

The first weekend I was allowed home, I was so excited. Mum and Dad came to pick me up and we went home together on the tube.

I kept thinking about climbing into my old bed, seeing Natalie and my friends. And best of all, I wouldn’t have to eat as much as in hospital. Re-sult!

‘Am I going to have to eat this weekend?’ I asked Mum as the train doors slid shut at Elephant & Castle.

‘Yes, you are,’ Mum replied firmly. ‘We’ve been instructed by the hospital exactly what you have to eat – they have given us menu sheets and told us how much weight you’ve got to maintain over the weekend. So you have to eat.’

Mum and Dad would take it in turns to pick me up for ‘home weekends’. Their divorce was finalised in July that year but they were still living under the same roof and on reasonable enough terms to present a united front to me. You didn’t have to dig far below the surface, though, to hit a wall of mutual resentment between them.

The moment I walked out of the gates of the Maudsley on a Friday evening, rush-hour traffic roaring up and down Denmark Hill, I felt elated, free and victorious that Mum and Dad were there together to pick me up.

But by the time I’d stepped through my front door an hour and a half later my thoughts had already turned to how I was going to get out of eating between then and Sunday night. My goal for home weekends soon became purely to lose the weight I’d had to put on during the week – and I’d do my damnedest to achieve it.

Relations with Nat could be pretty fraught on my home weekends too. In the months I’d been away she had been transformed from ‘Natalie Grahame’ to ‘Nikki Grahame’s sister’. At school she felt other kids and teachers only wanted to talk about me and how I was getting on, when I might be back and if I was feeling any better.

Things were tense between Natalie and Dad too, as she was mad at him about the divorce. She had always been closer to Mum than to him and in some ways had been quite pleased at first that they were splitting up because she felt he had been so horrid to Mum. But then Nat didn’t want Tony being close to Mum either. So she was mad at Dad for allowing that to happen too.

There was certainly a lot of anger in our house back then. Some of the doctors were concerned about me returning to that environment at weekends but Mum and Dad could have been attacking each other with chainsaws as far as I was concerned – I just wanted to be at home.

Yet as the weeks rolled by, home visits became more and more about skipping meals and exercising secretly in my bedroom than about seeing my family. In fact the longer I stayed away from home the less I cared about Mum and Dad, Nat, friends, school, gymnastics, everything really. All I could think about was how I was going to lose all the weight they had made me put on in hospital. But while I was at the Maudsley I complied with their rules.

Each morning after breakfast of a bowl of cereal and a slice of toast we would go to the hospital’s classroom. It wasn’t like a proper school but it was OK. I did a project about flowers, learning their names and colouring in pictures. That took us up to lunchtime – and one of their stomach-churning meals.

Then, in the afternoons, we would either go to the park or play outside. The Maudsley offered us lots of things to do and sometimes we did have fun. There was a toy room, an art room, a gym and a Sega room where you could play computer games. We could watch telly and videos too. My favourite video was Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. I watched it over and over again and loved the bit where the Golden Ticket-winning kids were allowed inside the factory. I’d look at all the chocolate and think, Oh, I wish I could eat that. But I knew there was absolutely no way I could allow myself – the guilt would be too unbearable.

There was also a day room where we’d sit around and do jigsaws or play board games like Buckaroo and draw Spirograph pictures.

In the evenings I’d write letters to Mum. Each week she sent me writing paper and stamps and I’d spend hours drawing pictures and writing notes for her and my friends from school. By now I’d been gone a matter of months and almost every day letters decorated with childish colourings and stickers arrived from my old classmates. I glued them up all around my room.

Evening was also the time for us kids to visit the tuck shop. Of course all the other children were beyond excited about that – but I hated it. The doctors encouraged Mum and Dad to give me 50 pence a week to spend on sweets. But why on earth would I want to do that? I was already eating massive meals every day. I didn’t want to spend money on sweets in the evenings. I wanted to buy comics and magazines but the staff weren’t having any of that. It was Chewits, Chewits and more Chewits. Sweets felt like a punishment to me.

There were some good times at the Maudsley, though. One time they took us camping in the New Forest for a few days. One of the nurses, Clive, left a trail of red paint through the woods and we had to follow it. It was such a laugh just doing normal kids’ stuff.

But even that trip had its moments. Mary was there and one morning she said to me, ‘It’s snack time, Nikki. You can have a packet of crisps and a fizzy drink.’

‘I can’t eat crisps,’ I said. ‘I can’t.’

Mary barely looked up and just threw four biscuits at me instead.

The following evening everyone else was making warm bananas with melted chocolate around the camp fire. ‘Can I have my banana cold, on its own, please?’ I asked. Mary tossed the banana in my direction with a look of disgust.

They also took us on trips around London and to the Water Palace in Croydon, an indoor water park. It was fun, but there was a lot of crying and shouting too.

At the hospital there was an occupational therapist called Charlotte. Her job was to help me express my feelings through art and crafts. I liked making things but I just wasn’t interested in her constant questions about my mum. Did she watch what she ate? Had she encouraged me to diet? Did I get on with her? It all seemed so irrelevant. Why couldn’t everyone just leave me alone to eat – and not eat – exactly what I wanted? What none of them realised was that I couldn’t give a toss about getting better. I just wanted to get out.

The staff did try really hard to make us kids feel comfortable. There was a young nurse called Billy who everyone thought was really cool. And there was lovely Pauline who used to cuddle me when I was sad.

Clive was cool too. But one morning he said to me, ‘You’re filling out a bit.’ Surely anyone – most of all a qualified nurse – would know that is not the sort of thing you say to an anorexic. That had a massive effect on me. I already hated what they were doing to my body. I could feel my thighs become softer and see my tummy getting rounder and it disgusted me. I was gutted that they were undoing all the work I’d done to my body over the past year. So for Clive to then say I was filling out threw me into a new depression.

But worst of all the nurses was Mary. I remained terrified of her until the day I left the Maudsley. She would stand behind me during meals and make me scrape every last scrap of food off my plate. If I didn’t finish it, she’d tell me off. I was still just a child and found her really frightening.

If any of us played up we were given a certain number of ‘minutes’ to stand and face the wall. Mary was always handing out the minutes to me for being cheeky by saying ‘Shut up’ to the nurses or even a couple of times ‘I hate you’ when they made me eat something I couldn’t face.

One of the nurses would read me a story when I got into bed but when she turned the light out there were no cuddles or goodnight kisses like at home. Often I would lie there and quietly cry. About missing Mum, missing Dad, being stuck in hospital and another destroyed Felt by Numbers.

Other nights I’d feel stronger and make plans about what I’d do when I got out of there, how I’d set about losing the weight they’d made me put on and how I’d get back in control of my life. All I could focus on was the day they would let me home. To reach that day, though, I knew I just had to get on with doing what I was told and so I did start gaining weight.

After a couple of months of eating all my meals properly, sitting at the table in my cubicle, I was allowed to eat in the main sitting area, although my table was still shoved so that I was facing the wall with a member of staff sitting next to me.

When I’d done that OK for a month, I was allowed to eat in a downstairs office, although still it was only a blank wall and a nurse for company.

Then finally, four months after arriving at the Maudsley, I was allowed to eat my meals with the other children in the main dining room. Chatting and giggling during meals again was fantastic. I felt normal. There were three tables in the children’s dining room: the Dinosaur table, the Happy Eaters table and the Care Bears table. They put me on the Happy Eaters table! What a joke that was. If only it had been funny.

It had taken me virtually my entire stay at the Maudsley to work my way up to that table but it meant I was one of the kids who behaved during mealtimes and, most importantly for my doctors, I was eating my meals.

At the beginning of September, after six months at the hospital, I was told I would be going home. I’d gained 6 kilos (13 lb), to bring my weight up to 26 kilos (4 stone 1 lb) and although still skinny I was closer to the average weight for a child of my age.

But although on the outside I appeared to have recovered, inside my head I was still as intent on starving myself as the day I’d arrived there. If anything, I was more determined than ever. The big difference was that I was now far cleverer at fooling people about what I was thinking.

To celebrate my last day at the Maudsley the staff treated all the kids on the unit to a McDonald’s. I ordered a hamburger, chips and a strawberry milkshake and hated every minute of it. For me the entire trip was a nightmare, although the other kids were having a great time. I ate and drank with a smile on my face, making sure everyone thought I’d come through my problems and was as right as rain again.

But in my mind there was no doubt – as soon as I was home the starving would begin. And this time it was going to be serious.