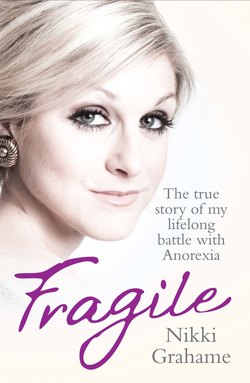

Читать книгу Fragile - The true story of my lifelong battle with anorexia - Nikki Grahame - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

NEVER GIVE IN

ОглавлениеSo why was I doing it? I can imagine that a lot of people reading this will find it totally weird that someone should want to put themselves through the pain and misery of starving themselves. Not to mention all the upset and stress it causes for their family.

As an eight-year-old I had no idea about the big ‘why’ behind it all – it was just something I had to do. A bit like other girls had to get every single badge at Brownies or had to get 100 per cent in a spelling test. But this was obviously more compulsive. And potentially fatal too.

Some of the anorexia counsellors I’ve had have said that maybe my eating disorder started as a bid to make myself literally disappear in the warring situation at home, as if by physically getting smaller I would just fade from view. And another expert said he thought I simply went on a hunger strike that got out of control. He thought I was so angry and devastated at how my perfect life had been shattered that I was refusing to eat until someone picked up all the pieces and put them back together again.

Counsellors have also quizzed me endlessly about my mum and whether she was to blame in some way but I really don’t think so. Mum has always been slim but not skinny and I never remember her dieting. But I do once recall her taking me and Nat to Folkestone for a weekend just when things were starting to go badly wrong with Dad. She was really stressed and hadn’t been eating properly. She stood in the hotel bedroom admiring her flat tummy in the mirror and said, ‘Ooh, I’ve really lost weight.’ But I honestly don’t think that alone could have caused it – there can’t be a woman in the country who hasn’t said something similar at some stage and not all their daughters have become anorexic.

Another counsellor – trust me, I’ve seen dozens – thought that on some subconscious level I was trying to copy the way Grandad had just faded away from life. He reckoned it was a ‘mourning reaction’ and I was trying to identify with Grandad by losing weight myself. And while I guess there might be some truth in that, part of me still thinks I would have become anorexic whatever happened. It was in my nature from before I was born, and the events of that year only brought it on at that particular time.

I also believe that anorexia just gave me something for myself that year as my life fell apart. I felt unhappy about everything that had happened, useless at gymnastics and inadequate at keeping my family together. But not eating was something I was good at. Not eating became my hobby, something that was all mine and that I could be in control of while my family and my perfect life fell apart around me.

In fact how much I ate was about the only thing I could control in the deepening chaos. And maybe I began to realise that not eating actually brought me quite a lot of control. Very soon I was pulling all the strings in my family. Mum’s every waking moment became filled with begging me to eat, pacifying my moods, sorting out my medical support and worrying about me. And while I remained anorexic, all her attention remained focused on me.

And as I’d always wanted to be the best at everything I did, long before I’d even heard the word ‘anorexic’ I’d set about becoming the very best anorexic ever.

I didn’t tell Natalie what I was doing and she never asked. I didn’t tell my friends and certainly not Dad. And when Mum asked, begged or pleaded with me to tell her what the problem was, I simply denied there was a problem.

Even though I’d started depriving myself of food to get skinnier for gymnastics, that soon went out of the window and before long losing weight became an end in itself. In fact my gymnastics was only getting worse as by losing weight I was also losing muscle. I couldn’t do the flips, I couldn’t jump, I couldn’t do rolls any more – and that made me feel even more useless.

Then, just as you might have imagined things couldn’t have got much worse at home, they did – with bells on! Dad found out that Mum had started seeing another man. Even though they were supposed to be separated despite living under the same roof, he went mad.

It wasn’t even as though Mum was having some mad, passionate affair. She’d just struck up a friendship with a bloke called Tony who used to pop round to fix her old Morris Minor whenever it broken down – which was pretty often!

Natalie and I had always quite liked Tony. We’d usually be playing out in the street on our bikes while he messed around under the bonnet. He’d talk to us and ask about school and he seemed harmless and friendly. After he had finished on the car he would go inside to wash the grease off his hands and have a cuppa and a chat with Mum. And that is how it all started. Tony’s marriage had been a bit rocky and I think he and Mum were two lost souls clinging to each other for a bit of comfort.

Natalie and I worked out what had been going on when the rows in our house reached volcanic proportions.

But, despite Dad’s jealousy, there was no way Mum was ditching Tony and having Dad back. Because what I didn’t know then was that, all through what I’d thought of as my perfect early years, my dad had been having a string of affairs.

Natalie was just nine months old when Mum and Dad had decided to have another baby and Mum fell pregnant almost immediately. But around the same time Dad started going out most nights with his mates, leaving Mum looking after a small baby alone and expecting another.

It was only one day when she found a long blonde hair wrapped around one of his socks as she filled the washing machine that everything became clear. Dad admitted it all. It was a woman who worked in one of our local shops. What a cliché! But it was easy, I guess – and so was she.

I love it when Mum tells the story about how she threw her best coat on, strapped Natalie in the buggy and marched up to the counter of the shop, pushing in front of all the other customers.

‘I hear you’ve been screwing my husband,’ she said calmly to the woman, suddenly finding herself the centre of attention in the shop as all the other customers listened in.

‘Leave him alone,’ Mum said determinedly.

‘Are you threatening me?’ the woman sneered.

‘You’re bloody right I am,’ said Mum, spinning the buggy round and storming out.

I’ve always liked to think that moment was Mum’s victory over a woman with the stunted imagination, let alone morals, to shag a man with kids. But it was a hollow victory. That weekend Mum miscarried the baby. She’d lost an unborn child and her belief in what her marriage had been.

Mum said everyone was entitled to make a mistake and agreed to take Dad back so long as he promised never to do it again. He said he couldn’t promise but he’d try. Some commitment, eh? Anyway she took him back.

Mum says a string of ‘other women’ followed over the years, which is why when she finally called time on the marriage, she really couldn’t go back.

It wasn’t until I was older that Mum told me about Dad’s affairs, but I picked up enough information from ear-wigging their rows at the time to have a pretty good idea what was going on.

I’d always been such a Daddy’s girl, I’d adored him, and finding out that my dad wasn’t who I thought he was hit me hard. I felt betrayed.

Tony started coming round quite a bit in the evenings. He would hold Mum when she cried about Dad, and Grandad, and me. If he’d known at that time what he was taking on by getting involved with Mum and all of us, he would probably have run for the hills! But he was kind and caring and he stuck around. He would come round a lot when Dad wasn’t there, which was another huge jolt for me and Natalie. It just confirmed for us that we were never going to get our old life back. The only thing that softened the blow was that we both liked Tony. We called him Hog because his hair stuck up like a hedgehog’s bristles. He didn’t even seem to mind too much when we took the mickey out of him.

Mum, Natalie and I were still living in the attic because Dad was refusing to move out of the house. There was a court battle pending over who would keep the house and it was becoming really nasty. Dad instructed one of his American cousins, a hotshot lawyer from New York, to act on his behalf. And then a few times this really scary heavy bloke came round saying, ‘We’re going to make you an offer – you should take it.’

But Mum had nowhere to go to, so we stayed in the house, living like normal downstairs during the day when Dad was at work, then scuttling up to the attic each evening. We’d sit up there watching television and hear Dad walking around downstairs singing manically. It was like something out of a horror film.

One night it kicked off really badly between Mum and Dad. There was screaming and shouting downstairs, a smashed teapot and so much anger. I lay in bed, the pillow over my head to dull the noise as I cried and cried.

After that night Mum applied for a restraining order against Dad. In the end, though, she let him back into the house and the court case over what they should do with our home rumbled on.

In January 1991 Mum filed for divorce and my perfect life was well and truly over. That same month Dad finally lost his job and it was obvious that sooner or later we’d have to move out of my beloved Stanley Road.

Things at school were going rapidly downhill too. I started spending most of my days sitting in the medical room with the school nurse, Mrs Bullock. My teachers didn’t mind because they could tell I was very weak. I looked awful and hadn’t been concentrating on my lessons for months. Mum had told them about the problems at home and maybe they thought I was just going through a difficult patch and I’d pull through soon.

Mrs Bullock became a surrogate mother for me in the hours when I had to be away from my real mum. I loved her and wanted her total attention all the time. If another pupil dared to come to the medical room with a cut knee or something wrong with them and needed Mrs Bullock, I couldn’t bear it. I would pace up and down, feeling angry and anxious. This is my room, I’d say to myself. I need Mrs Bullock – she’s for me and me only.

By the beginning of 1991 I had reduced what I would allow myself to eat more and more until it was virtually nothing. For breakfast it would be one small glass full of hot orange squash and four cubes of fruit salad. Then Mrs Bullock would give me tea and two digestive biscuits in the medical room, which would be my lunch. Obviously she knew that wasn’t enough, but I think she too was grateful to think I was getting something inside me.

I negotiated with Mum – or should I say bullied her? – into letting me eat my evening meals out of a peanut bowl. If she ever tried to serve something up on a normal dinner plate I’d just freak, push the whole lot away and refuse to eat anything at all.

But even a peanut bowl-sized portion was no guarantee I would eat. For a normal dinner I would allow myself ten strands of spaghetti or two small potatoes with some vegetables. And when I had eaten the amount I’d decided was acceptable, that was it, I’d stop eating and however much Mum begged, cajoled or shouted at me, nothing would change my mind.

And all the time she was growing more and more terrified and frustrated as the weight fell off me.

We went to the doctor four or five times but each time it was a locum and he was insistent it was ‘just a phase’ or ‘girls being girls’ and ‘something I would grow out of’. How wrong could he be?

My doctor’s notes at the end of 1990 recorded my weight as 21.4 kilograms (3 stone 5 lb). By February 1991 it had dropped to 21 kilos (3 stone 4 lb). The locum described me as: ‘Very quiet, introvert and controlled. Reluctant to open up. Kneading her hands and tearing up the Kleenex given to her when she started to cry.’ But he still sent me home again.

I was also suffering from Raynaud’s Disease, which affects blood flow to the extremities and means you are incredibly sensitive to the cold. But by then I had so little body fat protecting me that it was hardly surprising.

One evening things hit a new low at home. Mum had cooked dinner, so again I trailed up to the table, sat down, looked at my peanut bowl and point-blank refused to eat. Normally Mum would try to persuade me at first, but this time she just lost it.

‘I can’t stand this any more,’ she screamed. ‘Are you trying to kill yourself?’

She dragged me to the floor and with one hand held me down by my hair while with the other hand she scooped up fistfuls of pasta and tried to force them into my mouth. I was screaming, clawing at her and trying to push her off me. Then I clamped my lips shut. Whatever she did, she wasn’t going to make me eat.

Another time Natalie and I had gone shopping with my auntie and Mum for bridesmaids’ dresses because my cousin was getting married. We were in the restaurant in Debenhams and Mum ordered us fish and chips. But when it arrived I picked at a few peas, then pushed it away.

Mum went mad. She held me down on the chair with one hand and tried to force the chips in my mouth with a fork. I was shouting and crying at her to stop but she was raging. My auntie was shouting, ‘Sue, stop it! Calm down, Sue. Leave her.’ But Mum couldn’t. She was terrified at what was happening to me and overwhelmed with frustration that she couldn’t do anything about it. Nothing she had tried was working, the doctors still weren’t taking her seriously and I was fading away in front of her eyes.

As the weeks went by I became weaker and weaker and was feeling so out of it at school that one day the headmistress called Mum in for a meeting. She said the school couldn’t deal with the responsibility of having me there any longer while I was so ill and I’d have to take some time off.

So that was it, no more school. But by then I was so tired and weak I was beyond caring. I became so weak and helpless that I’d get Mum to carry me around the house. I loved that. I could still have walked if I’d had to, but being carried made me feel like a baby again – it felt safe.

The state I was in gave Mum and Dad a whole new subject to row about. Dad blamed Mum, saying I’d got worse since she’d filed for divorce. Mum blamed Dad for, well, everything that had happened really.

Then, by the February of that year, I’d reduced what I would allow myself to water – which I’d only agree to drink out of one particular sherry glass from the kitchen cabinet – vitamin C pills and the occasional slice of toast or shortbread biscuit.

I was painfully skinny but not only had all my body fat gone, so had my spirit, my energy and my childishness.

Lying on our battered brown corduroy sofa watching television, I was locked in a world far away from everything going on around me. I was unable to concentrate on anything, play with toys, think or even move very much.

For a fortnight I ate virtually nothing at all. I chewed gobstoppers to keep away hunger pangs. And I screamed and lashed out if Mum or Dad tried to make me eat. I was so weak that at night I had to crawl up the stairs to bed as Mum tried to help, tears rolling down her face on to the carpet.

You might wonder why she wasn’t dialling 999 or camping outside the doctor’s front door, but she had been told so many times I’d just ‘snap out of it’ that she had lost all confidence in the system – and in herself. Her self-esteem was shot to pieces after everything she had been through and she had no strength left to fight. But one morning at the beginning of March she knew she couldn’t leave it another day. She helped me into the car and drove me to the GP’s surgery.

When we arrived she helped me out of the car and we found ourselves a seat in the stuffy waiting room. Mum went up to the receptionist and quietly but determinedly stated her case. ‘My daughter is very ill,’ she said. ‘I can’t cope any more. We are going to sit here and we’re not leaving until someone does something to help her.’

This time it took the doctor just one look at me to tell I was dangerously ill. I was malnourished and extremely weak. But most urgent was the fact that I had become severely dehydrated.

I was so tired I hadn’t got the strength to lie when the doctor asked what I’d eaten that day. And Mum was doing all the talking this time anyway. The previous day I’d had a quarter of a slice of toast for breakfast, no lunch and two slices of bread and a fish finger for my dinner. That was all.

The doctors weighed me and I was just 20 kilos (3 stone 2 lb). I had a BMI of 12.4, which meant I was severely underweight. A normal eight-year-old would be around 27 kilos (4 stone 4 lb) – that’s 7 kilos, or more than a stone, heavier than I was.

The doctor promised Mum that by the following day they would have found me a specialist unit where I could be assessed and helped. He turned to me and said, ‘Now go home and eat something – it’ll be your only hope of staying out of hospital.’

When we got home Mum heated up a Cornish pasty for me in the microwave and I ate the lot. It was delicious. After so many weeks of eating almost nothing, it felt amazing.

But within an hour of finishing it, a huge wave of guilt surged over me. I hated myself for being so weak and giving in. You must not do that again, I reprimanded myself.

I went to bed feeling angry at myself and guilt-stricken about how much I’d eaten. And I was terrified of what the morning would bring.