Читать книгу Canaletto - Octave Uzanne - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

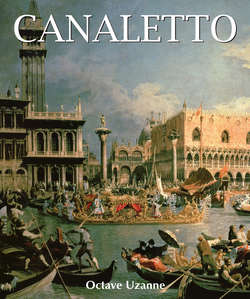

Venice during the Eighteenth Century

Venetian Society

ОглавлениеThe famous city of Venice holds a special kind of influence over enthusiasts who are passionate about eighteenth century art. Indeed, one is at a loss to imagine a more marvellous setting for such a sensual society, always ready to enjoy life, and not worried about tomorrow. What more dignified atmosphere could so assuredly attract poets and painters? What a theme for the writer whose pen is akin to the colourist’s brush and the goldsmith’s chisel? Seduced by the beauty of this tableau and the lively allure of its characters, Théophile Gautier thought long and hard about how to describe and put new life into the city of Doges with a narrative that would trace the local mores of this exuberant and frivolous population. This novel was often pondered in the master’s imagination, but was never written. However, we do find elements of the novel scattered throughout the memoirs of his contemporaries, and we find the same framework in the paintings of Canaletto. With equal interest, one can consult the memoirs of the most informed witnesses, such as Goldoni, Gozzi and Casanova, or, better yet, those by travellers with a trained eye and nimble tongue like Charles de Brosses and François Joachim de Pierre de Bernis.

In a light and at times teasing tone, the correspondence of de Brosses offered the most appealing portrait of Italy to eighteenth century society. Departing with several other gentlemen in the spring of 1739, Charles de Brosses, a spirited yet serious man, was determined to make these ten months serve both for pleasure and instruction. At the time, he was thirty years old and had been an adviser since the age of twenty-one. He was gifted with a mental acuity quite rare in young men, adding to his vast knowledge great perceptiveness and extremely sound judgement, to which his letters bear witness. Before occupying the office of principal magistrate, he found Venice so seductive that he thought about asking for the position of ambassador to the Venetian Republic. However, this observation post, located in southern Europe, being rather difficult to obtain, he revoked his candidature and the Abbot of Bernis filled the post fifteen years later.

A good judge of character, and rather difficult to please for this reason, Bernis, during his short mission, knew how to gain recognition for his style of governing, his personal aptitudes and his character. Thus, his memory lived on long after his departure. Having had several disputes with Venice, Pope Benedict XIV turned to him to mediate. Immediately receiving the approval of the opposing party, the future cardinal was able to settle the disagreement between Rome and Venice, satisfying both sides. No doubt, the success of his intervention contributed to his earning the red hat. The dispatches sent by Bernis during his ambassadorship were quite thorough and filled with very fine remarks written in excellent French, pleasing Louis XV. Judging his representative capable of more important services, the king called him back to France in 1757.

4. The Canale di Santa Chiara looking North towards the Lagoon, c. 1723–1724.

Oil on canvas, 46.7 × 77.9 cm.

The Royal Collection, London.

Before addressing Giovanni Antonio Canaletto’s life and his work, it behoves us to draw a portrait of his birthplace and contemporaries. This is particularly important because at that time, perhaps more than at any other, art, literature and entertainment shared a joint development. Could one truly understand the origin and progression of the master’s talent, his intellectual habits and work methods, without first understanding the society of which he was a member?

Taking an initial glance at Venice’s history, one cannot but be filled with wonder by the powerful energy and the expansive force of its people, enclosed as they are within such narrow limits. The city was thus stimulated by the most ardent patriotism; the prosperity and existence of each being inextricably linked to the interests of the city. Yet nothing is more modest than the origins of this small village of boatmen, nothing more desolate than the sands on which the first bands of fugitives settled. Nevertheless, nothing can match the heights reached by this Republic capable of launching a fleet of five hundred ships into the Bosporus, of navigating three thousand vessels together, and of developing, with the most diverse elements, an original artistic tradition. In this way, Venice assured its standing among the great kingdoms of Europe. With need for neither barriers nor fortifications, being well protected from warships by its shallow lagoons, the city could not be overtaken by outside forces. With a footing in the Middle East and Cyprus, the city continued its crusade along the Mediterranean coastline in Morea and on the island of Candia. Venetian soldiers never lagged in the war against the infidel. At Lepanto, for example, Venice furnished half of the Christian fleet.

Nevertheless, although the military spirit, which quickly died out in the neighbouring principalities, survived over a longer period in Venice, the city’s prestige started to diminish. Geographical discoveries brought a fatal blow to its commerce and the Portuguese soon inherited all the traffic headed for Asia. Politics, carried out by a jealous oligarchy that flattered the Epicurean tendencies of the people, finally got the better of the city’s bellicose behaviour and wish for power.

Of this government steeped in prestige, luxury and a terrible threat of torture, today we are familiar with its infernal police and secret dungeons, all the exterior workings that supplied the Romantic period with the subjects for so many plays and paintings. We know about the Council of Ten, whose masked judges met only at night, the room from which the accused departed only to disappear forever, and “the leads”, the prison under the Doges’ Palace from which Casanova managed to escape in an act of prodigious will. What hasn’t been said about the three state inquisitors and their irrevocable sentences, about the boat with the red lantern light that would stop under the Bridge of Sighs before floating past Giudecca towards the Orfano canal, where deep waters enshrouded their victims and their secrets, where fishermen were prohibited from casting their nets? A row of wooden stilts indicated the waters where the boat would stop. Still today, one of the posts supports, with a lamp lit by gondoliers, the tiny chapel that received the last prayer of these supplicants.

In the eighteenth century, a new political atmosphere was definitively set in place. Venice’s prestigious history was over and the careers of great artists and great patriots were forever ended. In vain did Francesco Morosini,[1] for his prowess in Morea and on Candia Island, earn the nickname “Peloponnesiac”. In vain did the old Marshal Schulembourg, who served twenty-eight years as General of the Republican Armies, merit the honour of an equestrian statue in Corfu Square. The lion of Saint Mark drew in its claws and the Queen of the Adriatic dozed off into a voluptuous nonchalance that only the bells of a masquerade could trouble. Moreover, the leaders kept up a system of perpetual amusement for the population. They thought this the most prudent method of guarding against intrigues, as this was the surest way to divert people’s minds from unsettling preoccupations. For Venetians, who were naturally drawn to lavishness and superficial appearances, and who were located somewhere between unlimited freedom, as far as pleasure was concerned, and an absolute prohibition against discussing the actions of those in power, constant celebrations and the most rowdy of pleasures became a necessity. In this Cytherean court, which had never produced a Watteau, there was an overabundance of gaiety and the decadence was, at least, as sweet and bright as an evening on the banks of the lagoons.

5. Entrance to the Grand Canal from the Molo, Venice, 1742–1744.

Oil on canvas, 114.5 × 153.5 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.

6. The Grand Canal, from the Foscari Palace, c. 1735.

Oil on canvas, 57.2 × 92.7 cm.

Private Collection.

7. The Grand Canal: looking South-east from the Campo Santa Sophia to the Rialto Bridge, c. 1756.

Oil on canvas, 119 × 185 cm.

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin.

8. The Grand Canal from the Fondamenta della Croce, c. 1734.

Pencil and dark ink, 26.9 × 37.6 cm.

The Royal Collection, London.

1

Francisco Morosini, after experiencing the effects of Venice’s political jealousy, was appointed Generalissimo. In 1688, honour was bestowed upon his glorious name. He was then elected doge. The pope sent him a sword and helmet because of his role as Defender of the Faith.