Читать книгу Canaletto - Octave Uzanne - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Venice during the Eighteenth Century

Theatrical Arts, Poetry and Painting

ОглавлениеThe fame of Venetian critics, men of letters and poets extended well beyond the lagoons. The Viennese court looked to them for its poeta Cesareo, more than once. The University of Padua turned to Gaspard Gozzi when they needed a general revision of its constitutions and a new studies plan. With the exception of Metastasio, considered the greatest lyricist of his time, all the poets cherished by Italy, including Apostolo Zeno, Chiari, Goldoni and both of the Gozzis, were all Venetian subjects, by either birth or adoption. The use of verse was therefore constant; indeed every public ceremony or family event provided an excuse to write several stanzes, which made up a large part of each of these authors’ works.

Meetings between the finest minds of the time were set up to reform taste, maintain the purity of Italian style and defend national spirit. One such academy was degli Animosi, established in 1691, whose founder Apostolo Zeno[5] was no less famous for his dramatic works than for his erudition. Its members were the Magliabecchis, the Salvinis and the Redis. There was also the Granelleschi company, less serious but no less active, formed under the auspices of the Gozzi brothers, of whom Gaspard, the fervent elder brother, drew his inspiration from Dante and Petrarch, while the younger Charles, who had a more aggressive personality, preferred to focus on the comic aspect of things. They were surrounded by the splendid amateurs, Joseph and Daniel Farsetti, the latter of whom, a bailiff for the Order of Malta, turned out some very elegant verses, the Abbot Natale Lastesio, one of the most knowledgeable savants of his time, Forcellini and the two patricians, Crotta and Balbi, all of whom made up an elite group in which each member distinguished himself by a liveliness of spirit and a depth of knowledge. At their meetings, these unique academicians only approached their work after they had exhausted every extravagant thought. To get more out of their group, they brought in an absurdly pretentious person named Secchellari. They sent a delegation to him after which they promoted him to the position of president of their group. It was precisely out of this mixture of buffoonery and serious work that a national character surfaced, whose epigrams, subdued and cynical, never lost their place. In reality the heavy-handed joking around did not stop this group from passionately defending the Venetian literary tradition, nor from gaining attention by the accuracy of its critiques, at times marked by malice or violence. Very conscious of his own elegance and style, Charles Gozzi relentlessly fought against Chiari’s[6] and Goldoni’s successes. Reproaching the latter for having ruined Italian theatre and for his harshly unrefined use of language, he made him the object of a biting satire entitled La Tartane, filled with references to recent events. This defence, published in 1757, scathingly ridiculed other playwrights and may have contributed to Goldoni’s departure for France.

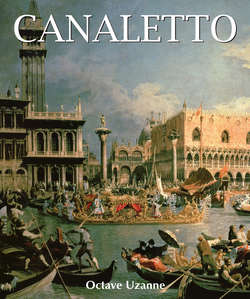

21. Reception of the French Ambassador in Venice, c. 1740.

Oil on canvas, 181 × 259.5 cm.

The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg.

Although similar academies were open to only a small circle of men of letters, there was a general passion for theatre. Important houses had private stages; thus one could see Goldoni’s grandfather staging plays and operas at a country house six leagues from Venice. Likewise, Gozzi’s father put on plays in his palace in which his children of both sexes appeared, who were fortunately endowed with talent. On the other hand, there were also many improvised, open-air theatres, operated almost continuously. To build two stages into a wall, some boards were the only expenses. Sometimes the platform was roofed with a lightweight cover. A single, painted canvas served as the scenery. Its dimensions closely resembled those of marionette theatres. Before a curious crowd, Canaletto, Marieschi and Tiepolo mimed in these makeshift theatres constructed near bell towers or other public places. Among the most important stages, three were especially reserved for plays. And the nobles did not feel that managing a theatre diminished their respectability. Gaspard Gozzi accepted this task until financial ruin and the dispersion of his troupe relieved him of his duty. Initially affiliated with the Saint Angelus Theatre, which was the most frequented but least conspicuous, Goldoni established himself with the Saint Luke’s theatre in 1748. It was there that he undertook, in spite of the conspiracies and sarcasm that were directed against him, a revolution in theatre, replacing masked characters with bare-faced actors, farces and gesticulatory plays with morality plays.

The success of these reforms could have ruined the celebrated Sacchi, a famous Harlequin who incarnated, so to speak, the old national genre. Once settled in Venice, and with a strong connection to Goldoni, Sacchi had assembled a troupe that had already begun to break up when Charles Gozzi became affiliated with it. The latter, who didn’t want to overlook anything that might make it possible for him to triumph over Goldoni, offered his collaboration for free. He lavished advice on his interpreters. He soon started to live among them as their good friend, and was most warmly applauded at the 1761 Carnival. Nowadays, we have lost our ability to appreciate these bizarre themes lifted from fairy tales and children’s stories, allowing the fanciful genius of these players to come alive in comic buffoonery. The following year, a wild farce, Il Re Cervo, occasioned a new success for the four main masked actors, one of whom was Signora Ricci. Although these follies caused Venetian audiences to forget about more serious-minded spectacles for a moment, they were unable to gain an upper hand over a genre that drew its inspiration from nature and which was based on a more genuine form of analysis. Not expecting to be able to impose his reforms without a process of transition, Goldoni kept the mask for improvised plays and reserved the noble comic for subjects that had been more thoroughly studied. He carried all this out so well that his theatrical taste was, once and for all, adopted throughout Italy. His memoirs include an exposé of his plays, as well as a narrative of his successes and trials and tribulations. When one leafs through these chapters that go on, one after the other, with a spicy kind of variety, one is astonished by the extent of the dramatist’s productivity and cannot help but admire his genius. They weren’t all excellent works, as much as they needed to be, perhaps because of their great quantity. Pure gold is rarely found anywhere without an alloy. And although Gozzi used a dialect other than Venetian, the style he used sometimes justified, because of its lack of elegance and lucidity, his sarcastic expression. Moreover, those who demand that comedy conceal its irony with hearty, genuine laughter are tempted to reproach the Italian writer for too much sentimentality, for not being scrupulous enough with the methods he used, while disapproving of them, and for sometimes resorting to depictions of poisoning that never shocked his regular audience, but which any person who was of a delicate disposition would find repugnant. In spite of his works’ weak points, he depicted, in a very true to life form, specific kinds of characters borrowed from Venetian society, and it would be unfair to dispute his gift for invention.

22. Venice: the Feast Day of Saint Roch, c. 1735.

Oil on canvas, 147.7 × 199.4 cm.

The National Gallery, London.

23. Campo San Angelo, c. 1732.

Oil on canvas, 46.5 × 77.5 cm.

Private Collection.

24. Piazza San Marco Looking South and West, 1763.

Oil on canvas, 56.5 × 102.9 cm.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles.

Unlike the citizens of Athens, who crowned Aristophanes with roses, even though he had just punished them with his biting satires, Goldoni’s countrymen never knew how to appreciate their poets’ value, and they let the most interesting one get away. On the occasion of the revival of Harlequin’s Child Lost and Found, a play written at the request of Cacchi by an Italian theatre that had been established in Paris, Goldoni went to France for a two-year engagement for which he would receive a respectable remuneration. A passionate admirer of Molière, whom he considered the greatest comic among the ancients and moderns, he always wanted to learn of France, its men of letters, and Parisian society so highly praised for its wit and from which he hoped to gain great praise for his talent. He was soon bound in service to Mesdames, the king’s daughters, as their Italian tutor. Though no real position in the court was available, in exchange for some lessons he gave to the unmarried Madame Adelaide, he was able to secure lodgings at Versailles. He took part in every voyage and attended the court’s shows. In the end, his protectors provided him with a payment of four thousand pounds and released him from all of his duties. Goldoni turned a deaf ear to requests sent to him from London, Portugal and his fellow countrymen, remaining in Paris. During 1771, the success of Le Bourru Bienfaisant, which played with the support of Molé, Reville and Madame Bellecour, was one of the most vivid joys of his life. By nicknaming him “the Italian Molière”, his contemporaries had certainly not overstepped the boundaries of truth any more than when they likened Metastasio to Sophocles.[7]

Along with these diverse poets, some exceptional women graced Venetian society with their charming spirits and talent. One was Luisa Bergalli who, although spending her youth in a cobbler’s workshop, married the noble, Count Gaspard Gozzi. Marvellously gifted, she excelled in embroidery and, before she gave herself over to letters, she learned how to paint from Rosalba. Her translations of Terence’s plays, which garnered praise from Apostolo Zeno, her canzone and diverse theatrical works all bore witness to her skills, which were some of the rarest. No less famous was Rosalba Carriera, nicknamed the “Queen of Pastels”, who was celebrated when she travelled to France. She sold her portraits for thirty zecchinos and Charles de Brosses offered her twenty-five gold louis for a Magdalene no larger than his hand and a mere copy of Correggio. Though we excessively praise her graceful manner and charming colours, on the other hand we tend to forget about her master, the noble Giovanni Antonio Lazzeri.

Although the decline in painting was more noticeable than the glory of its zenith, the Venetian school, fallen into a period when the masters were considered to be frivolous and friendly, still counted some outstanding names. The prestige of Giorgione, Titian, Veronese and Tintoretto had not died out in the least, but their examples were hardly ever followed. One was more likely to head in the direction of the Carracci brothers or Pierre de Carone, or towards eclectics like Giambologna, the mannerists of Rome, or the imitators of Caravaggio. Like them, Venetians exaggerated their effects and loaded their canvases with dark shadows that compromised the longevity of the painting. These tenebrous styles were in vogue at the end of the seventeenth century. Without regard for the great painting traditions, the following era attempted a renewal. All the individual talents that then manifested themselves generated interest, not to mention that their work was not defective. Thus, a group made up of artists like Ricci, Tiepolo, Canaletto, and several minor masters like Milinari, Guardi and Longhi, would form around an excellent designer like Gregorio Lazzarini. They all deserve to be remembered with praise.

25. The Piazzetta, with the Library and Campanile, looking West, c. 1735.

Pen and ink, 22.6 × 37.4 cm.

The Royal Collection, London.

26. View of Venice, Piazza San Marco and Piazzetta, c. 1740.

Oil on canvas, 67.3 × 102 cm.

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford.

Therefore, the artists’ movement had barely let up. Venice, with the resources that its two academies provided, remained one of the places in the world where young artists found it easier to initiate their technique. The government deserved credit for not having neglected anything as far as ensuring the protection and prosperity of local industry and art. It was the government that granted Briati the sole privilege of manufacturing and selling crystals styled after those from Bohemia, the importation of which was prohibited. In this way he came to manufacture the most sought-after chandeliers and mirrors in Europe.[8] In 1764, a decree was issued for an Academy of Fine Arts, which was to take the place of the old painters’ association. It opened in 1766, thanks to patrician support of the leadership’s plans.

The Venetian artists even reaped very respectable fame outside their own country. One day, one of the doge’s representatives to the pope asked Carlo Maratta to paint a canvas for the examination room. He was surprised that they would solicit an artist in Rome since they had Gregorio Lazzarini, considered the Raphael of his school, in Venice. Although Lazzarini had instructed Giambattista Tiepolo, nothing seems less compatible with the master’s wisdom than his disciple’s wildly alluring work. Tiepolo actually has more affinities with Piazzetta, whose religious compositions are characterised by feverish movement. Amidst ruined architecture, he places characters of tormented bearing, while a violent wind raises hanging draperies and tears away at the clouds. One can especially appreciate the quick, spirited style of execution in his oeuvre that marvellously adapts itself to the fresco. Painted with an array of pale gold and fine silver hues, the expansive compositions in which he loves to mix the flight of spirits with rays of light enchant the eye to such a degree that it one forgets about any weaknesses in his drawing. In spite of his critics, Tiepolo emerges as the heir apparent to the masters of detail, one of the greatest after Veronese. During this period, a school of landscape artists was also blossoming, including artists like Luca Carlavaris and Marco Ricci from whom Canaletto was going to distinguish himself.

However, although painting was drying up, music was flourishing and much appreciated. Born inside churches, it later became secularized beginning in the fifteenth century. People saw it as the necessary complement to a lavish existence, the typical companion at feasts where the ear needed to be charmed as much as the eye and the tongue. The greatest colourists passionately lent themselves to music in order to distract themselves from painting, manoeuvring the violin bow and the brush with equal ease. Later on, four homes for orphaned girls supplied singers from among their ranks to both Venetian stages and to theatres in all countries. An academy of music played along the banks of the canal almost every night. The commoners were no less passionate than the nobles about these concerts, and the two sides of the canal were always completely covered with people who hurried there to listen.

27. Venice: the Piazzetta towards the Torre dell’Orologio, 1727–1729.

Oil on canvas, 172.1 × 134.9 cm.

The Royal Collection, London.

28. The Piazza, looking North-east from the Procuratie Nuove, c. 1745.

Pencil and wash drawing ink, 22.8 × 33.3 cm.

The Royal Collection, London.

29. Piazza San Marco and the Colonnade, c. 1756.

Oil on canvas, 46.4 × 38.1 cm.

The National Gallery, London.

30. Saint Mark’s Square, looking South, c. 1723.

Oil on canvas, 73.5 × 94.5 cm.

Private Collection.

Goldoni informs us[9] that people also found delight in music during long trips. When he returned from Pavia to Venice with some friends, he rented a boat decorated with painted, carved ornaments. They made slow progress, with nothing regular but their pleasure and the nightly stop. Every one of them was a musician: one played the violoncello, three others the violin, another played the guitar and another a hunting horn. Goldoni compiled even the most minor incidents along the route in a journal he wrote in verse. And every evening, after their meal, he recited his poetry. Then, the improvised orchestra set up on the deck and residents applauded as the boat passed by. In Cremona, they gave them a great ovation and offered a banquet to this joyous band. Thus celebrated, the artists recommenced their concert with the help of other performers, and dancing went on until morning.

This example, chosen from about a thousand, shows how avidly joyous these people were, how they were induced to take life as it came, as pleasantly as they could, how they knew to enjoy every pleasure and exercise their intelligence by bringing such occasions to life. This passion for pleasure would cover over any other impressions for a while. When on certain days one saw a bustling and decked out Venice, why would anyone have suspected that it was in decline? Nevertheless, its irremediable downfall was accentuated even more during the second half of the eighteenth century, until it became absolute. The splendour of the ancient apotheoses made the contrast between the strengths of the past and the misery of the later time more obvious. Venice no longer resembled the triumphant queen that Veronese had painted under those imposing structures, being crowned by spirits and receiving acclamations from blossoming young women and splendid gentlemen. Wasn’t this city instead as Musset described it, “the poor old woman from the Lido”?

All of its energy seemed to have burned itself out. A kind of languor paralysed any effort. The silent palaces seemed to be abandoned and were deteriorating. Beggars made up a third of the population. Instead of harbouring flags from every country as in times past, the Giudecca Canal was almost empty, waiting for fleets that were never going to return. However, in the poor neighbourhoods, one could still find façades decorated with columns and picturesque corners that would tempt any painter. The Venice that had fallen from its supreme position, with all its memories, was still an appealing city. The evenings were so enchanting, with strings of lights lit up under the Procuratie arches, and conducive to thinking about all one had seen during the day. The flower vendors would approach, silently offering flowers without disturbing your daydream. Little by little, the crowds would grow thicker and strolling musicians would sing the arias of Bellini and Verdi or play a harp and violin concert. And down there, against a sky filled with twinkling stars, the dark mass of Saint Mark’s would be silhouetted while the dark arches over its entrances, barely lit up by some flames swaying to and fro, were dimly outlined.

31. Venice: Piazza San Marco with the Basilica and Campanile, c. 1725.

Oil on canvas, 135 × 172.8 cm.

The Royal Collection, London.

32. Venice: Piazza San Marco, c. 1756.

Oil on canvas, 46.4 × 37.8 cm.

The National Gallery, London.

33. The Crossing of San Marco, looking North, c. 1735.

Pencil and ink, 27.2 × 18.8 cm.

The Royal Collection, London.

34. Venice: the Interior of San Marco by Day, c. 1755–1756.

Oil on canvas, 36.5 × 33.5 cm.

The Royal Collection, London.

35. Interior Court of the Doges’ Palace, Venice, c. 1756.

Oil on canvas, 46.6 × 37.5 cm.

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

5

Apostolo Zeno, born in 1668, was not a noble, in the least, because his grandfather was not registered in the libro d’oro, even though he had illustrious roots. Unable to obtain a post at Saint Mark’s library, he accepted an offer from Emperor Charles VI, who granted him the position of court poet and historian. After twelve years in Vienna, esteemed for his character and talent, he transferred his position to Metastasio and returned to Venice in 1729. He lived there for two more years, among his friends, books and medals, laden with honours, and kept up active correspondence with foreign scholars. He composed sixty-three dramatic works in many different styles. Caldara set many of them to music. Among his operas, Gli Inganni Felice and Lucio Vero were particularly lauded.

6

Chiari, a comedic poet, originally from Brescia, settled in Venice and unsuccessfully tried his hand at novels and tragedies. Like Goldoni, for whom, at times, he was a lucky rival, he had adopted fourteen-syllable Martellian verse. The former inspired by the works of Terence, the latter endeavoured to stage the works of Plautus; both had their fanatic supporters. The sixty plays written by Chiari, in a style devoid of both conviction and elegance, at least did justice to the fecundity of his imagination.

7

Goldoni took on the position of Italian tutor once again, this time for Madame Clotilde, who was engaged to the Prince of Piedmont, and for Madame Elisabeth. He ended his career by writing three volumes of memoirs that were to serve as his life story and the history of his theatrical career. He died on January 8, 1793, saddened and impoverished by the Revolution.

8

Venice’s glass industry was very old. In 630, Saint Benedict called Venetian workers to England to decorate the windows of Yarmouth Monastery. Shops were set up on Murano Island and were closely monitored by the Council of Ten. During the eighteenth century, this art enjoyed new found prosperity, thanks to the patriotism of Briati, who had worked as a porter for three years in a Bohemian crystal shop so he could learn the secrets of fabrication. His perseverance was rewarded by success, as he obtained permission to rebuild his furnaces within the city limits of Venice. He died on January 17, 1772.

9

In his Memoirs, Part I, Chapter XII.